Introduction New Australian Opera

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RICHARD STRAUSS SALOME Rehearsal Room Vida Miknevičiūtė (Salome) PRESENTING VICTORIAN OPERA PRESENTS PARTNER SALOME OPERA in ONE ACT

RICHARD STRAUSS SALOME Rehearsal Room Vida Miknevičiūtė (Salome) PRESENTING VICTORIAN OPERA PRESENTS PARTNER SALOME OPERA IN ONE ACT Composer Richard Strauss Librettist Hedwig Lachmann Based on Oscar Wilde’s play Salomé Conductor Richard Mills AM Director Cameron Menzies Set Designer Christina Smith Costume Designer Anna Cordingley Lighting Designer Gavan Swift Choreographer Elizabeth Hill-Cooper CAST Salome Vida Miknevičiūtė Herod Ian Storey Jochanaan Daniel Sumegi Herodias Liane Keegan Narraboth James Egglestone Page of Herodias Dimity Shepherd Jews Paul Biencourt, Daniel Todd, Soldiers Alex Pokryshevsky, Timothy Reynolds, Carlos E. Bárcenas, Jerzy Kozlowski Raphael Wong Cappadocian Kiran Rajasingam Nazarenes Simon Meadows, Slave Kathryn Radcliffe Douglas Kelly with Orchestra Victoria Concertmaster Yi Wang 22, 25, 27 FEBRUARY 2020 Palais Theatre Original premiere 9 December 1905, Semperoper Dresden Duration 90 minutes, no interval Sung in German with English surtitles PRODUCTION PRODUCTION TEAM Production Manager Eduard Inglés Stage Manager Whitney McNamara Deputy Stage Manager Marina Milankovic Assistant Stage Manager Geetanjali Mishra MUSIC STAFF Repetiteurs Phoebe Briggs, Phillipa Safey ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Surtitles courtesy of Opera Australia ResolutionX, BAACLight Theatre, Lilydale Theatre Company © Anna Cordingley, Costume Designer P. 4 VICTORIAN OPERA 2020 SALOME ORCHESTRA CONCERTMASTER Sarah Cuming HORN Yi Wang * Philippa Gardner Section Principal Jasen Moulton VIOLIN Tania Hardy-Smith Chair supported by Mr Robert Albert Principal -

The Pomegranate Cycle

The Pomegranate Cycle: Reconfiguring opera through performance, technology & composition By Eve Elizabeth Klein Bachelor of Arts Honours (Music), Macquarie University, Sydney A PhD Submission for the Department of Music and Sound Faculty of Creative Industries Queensland University of Technology Brisbane, Australia 2011 ______________ Keywords Music. Opera. Women. Feminism. Composition. Technology. Sound Recording. Music Technology. Voice. Opera Singing. Vocal Pedagogy. The Pomegranate Cycle. Postmodernism. Classical Music. Musical Works. Virtual Orchestras. Persephone. Demeter. The Rape of Persephone. Nineteenth Century Music. Musical Canons. Repertory Opera. Opera & Violence. Opera & Rape. Opera & Death. Operatic Narratives. Postclassical Music. Electronica Opera. Popular Music & Opera. Experimental Opera. Feminist Musicology. Women & Composition. Contemporary Opera. Multimedia Opera. DIY. DIY & Music. DIY & Opera. Author’s Note Part of Chapter 7 has been previously published in: Klein, E., 2010. "Self-made CD: Texture and Narrative in Small-Run DIY CD Production". In Ø. Vågnes & A. Grønstad, eds. Coverscaping: Discovering Album Aesthetics. Museum Tusculanum Press. 2 Abstract The Pomegranate Cycle is a practice-led enquiry consisting of a creative work and an exegesis. This project investigates the potential of self-directed, technologically mediated composition as a means of reconfiguring gender stereotypes within the operatic tradition. This practice confronts two primary stereotypes: the positioning of female performing bodies within narratives of violence and the absence of women from authorial roles that construct and regulate the operatic tradition. The Pomegranate Cycle redresses these stereotypes by presenting a new narrative trajectory of healing for its central character, and by placing the singer inside the role of composer and producer. During the twentieth and early twenty-first century, operatic and classical music institutions have resisted incorporating works of living composers into their repertory. -

Emma Matthews

Emma Matthews Soprano Curriculum Vitae Opera Repertoire Monteverdi LIncoronazione di Poppea Damigella OA Gillian Whitehead Bride of fortune Fiorina WAO Offenbach Orpheus in the Underworld Cupid WAO Les Contes d’Hoffmann Olympia, Giulietta, Antonia, Stella OA, SOSA Berg Lulu Lulu, OA Handel Alcina Morgana OA Rinaldo Almirena OA Orlando Angelica OA Giulio Cesare Cleopatra OA Mozart Die Zauberflote Papagena, WAO, OA Pamina OA Queen of the Night OA Le Nozze di Figaro Barbarina WAO, OA Cherubino OA Idomeneo Ilia OA La Clemenza di Tito Servillia OA Die Entfuhrung aus dem Serail Blonde OA, Konstanze OA Mitridate, Re di Ponto Ismene, Sydney Festival Gilbert and Sullivan The Priates of Penzance Mabel OA The Mikado Yum Yum OA Alan Johns The Eighth Wonder Sky, Tour Guide Aunt Olive OA Bellini La Sonnambula Amina OA, SOSA I Capuleti e I Montecchi Giulietta OA Donizetti Lucia di Lammermoor Lucia OA, WAO La Fille du Regiment Marie OA L’Elisir d’amore Giannetta WAO Delibes Lakme Lakme OA Bizet Les Pecheurs de Perles Leila OA, WAO, OQ Janacek The Cunning Little Vixen The Vixen OA, ROH Richard Mills Batavia Zwaantie OA, WAO The Love of the Nightingale Philomele OA, WAO Gounod Romeo et Juliette Juliette OA Puccini Suor Angelica Genovieffa OA Kalman The Gypsy Princess Stasi OA J. Strauss Die Fledermaus Adele OA Massenet Werther Sophie OA R. Strauss Arabella Zdenka OA Der Rosenkavalier Sophie OA Rossini Il Barbiere di Siviglia Rosina OA, WAO Il Turco in Italia Fiorilla OA Il Signor Bruschino Sofia OA Verdi Un Ballo in Maschera Oscar OA Falstaff Nannetta OA Rigoletto Gilda OQ, OA La Traviata Violetta HOSH, OA Berlioz Beatrice et Benedict Hero OA Orchestral Repertoire Faure Requiem, Carmina Burana, C. -

Current Issue (PDF)

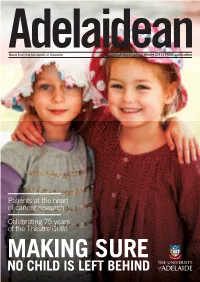

AdelaideanNews from the University of Adelaide www.adelaide.edu.au l Winter 2013 l FREE publication Patients at the heart of cancer research Celebrating 75 years of the Theatre Guild MAKING SURE NO CHILD IS LEFT BEHIND >ADELAIDEAN INSIDE THIS EDITION OF 06-07 10-11 ADELAIDEAN A new personal approach to treating cancer being pioneered by University of Adelaide researchers is giving victims a second chance of beating the disease. And we talk to the lead investigator on a data linkage research project that could change the way we take care of the youngest children in our community. 12-13 22-23 Also in this edition of Adelaidean we hear from the Deputy Vice Chancellor and Vice- >CONTENTS President (Academic) on the state of higher 03 Scholarship success for 12-13 Theatre Guild celebrates education in Australia, gifted students 75 years we visit the impressive, new dental simulation 04-05 Children the winners in 14-15 Food study for the gourmet laboratory and provide an data linkage project traveller insight into cutting-edge Simulation clinic fills gap in Melding music and words new technology called 06-07 16-17 dental training atomtronics . 18-19 App proves a game changer We also celebrate the 75th 08-09 A personal approach to for autistic children anniversary of the Theatre treating cancer Stop the chop Guild and talk to Anna 20-21 The university funding paradox Goldsworthy on her new 10-11 22-23 A perfect measure of success role at the Coetzee Centre for Creative Practice. Established in 1991, Adelaidean is the University of Adelaide’s free corporate magazine. -

Featuring the Brandenburg Choir Noël! Noël! Featuring the Brandenburg Choir

Noël! Noël! Featuring the Brandenburg Choir Noël! Noël! Featuring the Brandenburg Choir Morgan Balfour (San Francisco) soprano 2019 Australian Brandenburg Orchestra Brandenburg Choir SYDNEY Matthew Manchester Conductor City Recital Hall Paul Dyer AO Artistic Director, Conductor Saturday 14 December 5:00PM Saturday 14 December 7:30PM PROGRAM Wednesday 18 December 5:00PM Mendelssohn Hark! The Herald Angels Sing Wednesday 18 December 7:30PM Anonymous Sonata à 9 Gjeilo Prelude MELBOURNE Eccard Ich steh an deiner Krippen hier Melbourne Recital Centre Crüger Im finstern Stall, o Wunder groβ Saturday 7 December 5:00PM Palestrina ‘Kyrie’ from Missa Gabriel Archangelus Saturday 7 December 7:30PM Arbeau Ding Dong! Merrily on High Handel ‘Rejoice greatly, O daughter of Zion’ NEWTOWN from Messiah, HWV 56 Friday 6 December 7:00PM Head The Little Road to Bethlehem Gjeilo The Ground PARRAMATTA Tuesday 10 December 7:30PM Vivaldi La Folia, RV 63 Handel Eternal source of light divine, HWV 74 MOSMAN Traditional Deck the Hall Wednesday 11 December 7:00PM Traditional The Coventry Carol WAHROONGA Traditional O Little Town of Bethlehem Thursday 12 December 7:00PM Traditional God Rest Ye Merry, Gentlemen Palmer A Sparkling Christmas WOOLLAHRA Adam O Holy Night Monday 16 December 7:00PM Gruber Stille Nacht Anonymous O Come, All Ye Faithful CHAIRMAN’S 11 Proudly supporting our guest artists. Concert duration is approximately 75 minutes without an interval. Please note concert duration is approximate only and subject to change. We kindly request that you switch off all electronic devices prior to the performance. This concert will be broadcast on ABC Classic on 21 December at 8:00PM NOËL! NOËL! 1 Biography From our Principal Partner: Macquarie Group Paul Dyer Imagination & Connection Paul Dyer is one of Australia’s leading specialists On behalf of Macquarie Group, it is my great pleasure to in period performance. -

Koorie Perspectives in Curriculum Bulletin: January - February 2021

Koorie perspectives in Curriculum Bulletin: January - February 2021 This edition of the Koorie enrich your teaching program, see VAEAI’s Perspectives in Curriculum Bulletin Protocols for Koorie Education in Primary and features: Secondary Schools. For a summary of key Learning Areas and − Australia Day & The Great Debate Content Descriptions directly related to − The Aboriginal Tent Embassy Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander histories − The 1939 Cummeragunja Walk-off & and cultures within the Victorian Curriculum F- Dhungala – the Murray River 10, view or download the VCAA’s curriculum − Charles Perkins & the 1967 Freedom guide: Learning about Aboriginal and Torres Rides Strait Islander histories and cultures. − Anniversary of the National Apology − International Mother Language Day January − What’s on: Tune into the Arts Welcome to the first Koorie Perspectives in Australia Day, Survival Day and The Curriculum Bulletin for 2021. Focused on Great Debate Aboriginal Histories and Cultures, we aim to highlight Victorian Koorie voices, stories, A day off, a barbecue and fireworks? A achievements, leadership and connections, celebration of who we are as a nation? A day and suggest a range of activities and resources of mourning and invasion? A celebration of around key dates for starters. Of course any of survival? Australians hold many different views these topics can be taught at any time on what the 26th of January means to them. In throughout the school year and we encourage 2017 a number of councils controversially you to use these bulletins and VAEAI’s Koorie decided to no longer celebrate Australia Day Education Calendar for ongoing planning and on this day, and since then Change the Date ideas. -

Darkemu-Program.Pdf

1 Bringing the connection to the arts “Broadcast Australia is proud to partner with one of Australia’s most recognised and iconic performing arts companies, Bangarra Dance Theatre. We are committed to supporting the Bangarra community on their journey to create inspiring experiences that change society and bring cultures together. The strength of our partnership is defined by our shared passion of Photo: Daniel Boud Photo: SYDNEY | Sydney Opera House, 14 June – 14 July connecting people across Australia’s CANBERRA | Canberra Theatre Centre, 26 – 28 July vast landscape in metropolitan, PERTH | State Theatre Centre of WA, 2 – 5 August regional and remote communities.” BRISBANE | QPAC, 24 August – 1 September PETER LAMBOURNE MELBOURNE | Arts Centre Melbourne, 6 – 15 September CEO, BROADCAST AUSTRALIA broadcastaustralia.com.au Led by Artistic Director Stephen Page, we are Bangarra’s annual program includes a national in our 29th year, but our dance technique is tour of a world premiere work, performed in forged from more than 65,000 years of culture, Australia’s most iconic venues; a regional tour embodied with contemporary movement. The allowing audiences outside of capital cities company’s dancers are dynamic artists who the opportunity to experience Bangarra; and represent the pinnacle of Australian dance. an international tour to maintain our global WE ARE BANGARRA Each has a proud Aboriginal and/or Torres reputation for excellence. Strait Islander background, from various BANGARRA DANCE THEATRE IS AN ABORIGINAL Complementing Bangarra’s touring roster are locations across the country. AND TORRES STRAIT ISLANDER ORGANISATION AND ONE OF education programs, workshops and special AUSTRALIA’S LEADING PERFORMING ARTS COMPANIES, WIDELY Our relationships with Aboriginal and Torres performances and projects, planting the seeds for ACCLAIMED NATIONALLY AND AROUND THE WORLD FOR OUR Strait Islander communities are the heart of the next generation of performers and storytellers. -

Centre for the Study of Mothers' and Children's Health

031651 M&C A/R COV F/A 07/04/03 4:26 PM Page 2 centre for the study of mothers’ and children’s health annual report 2002 csmch annualcsmch report annualfebruary report 02.20012001/january - 01.2002 2002 page 2 La Trobe University La Trobe 031651 M&C A/R F/A 07/04/03 4:25 PM Page 1 centre for the study of mothers’ and children’s health annual report february 2002/january 2003 031651 M&C A/R F/A 07/04/03 4:25 PM Page 2 contents 4 CENTRE OVERVIEW 6 DIRECTOR’S REPORT 8 CURRENT RESEARCH PROGRAM 8 HEALTH SERVICES: PREGNANCY AND BIRTH 8 Randomised trial of pre-pregnancy information and counselling in inner-urban Melbourne 8 Obstetric ultrasound: its prevalence, timing and effectiveness in the diagnosis of congenital malformations 8 Victorian survey of recent mothers 2000 8 Having a baby in Victoria 1989-2000: women’s views of public and private models of care 9 Continuity of care: does it make a difference to women’s views and N Centre for the Study experiences of care? of Mothers’ & Children’s Health 9A new approach to supporting women in pregnancy (ANEW) Elgin St ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ 9 Evaluating practice and organisation of care at Southern Health and Sandringham Hospital (EPOCS) Melbourne University ■ ■ ■ 10 Debriefing after operative delivery: a randomised trial Swanston St Faraday St ■ ■ ■ ■ 10 Health and recovery after operative birth project (HARP) Tram Stop ■ 10 An exploratory study of domiciliary support during the first days 1 3 5 6 8 ■ 16 64 67 72 ■ following childbirth ■ ■ ■ -

Judith Wright and Elizabeth Bishop 53 CHRIS WALLACE-CRABBE Newspapers and Literature in Western Australia, 1829-1859 65 W

registered at gpo perth for transmiss ion by post as a periodical category B Ne,vspapers an~l Literature in S,.,~.n River Colony Judith Wright and ElifZ,.beth Bishop Vance Palnaer-A Profile UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA PRESS Giving the widest representation to Western Australian writers E. J. STORMON: The Salvado Memoirs $13.95 MARY ALBERTUS BAIN: Ancient Landmarks: A Social and Economic History of the Victoria District of Western Australia 1839-1894 $12.00 G. C. BoLTON: A Fine Country to Starve In $11.00 MERLE BIGNELL: The Fruit of the Country: A History of the Shire of Gnowangerup, Western Australia $12.50 R. A. FORSYTH: The Lost Pattern: Essays on the Emergent City Sensibility in Victorian England $13.60 L. BURROWS: Browning the Poet: An Introductory Study $8.25 T. GIBBONS: Rooms in the Darwin Hotel: Studies in English Literary Criticism and Ideas 1880-1920 $8.95 DoROTHY HEWETT, ED.: Sandgropers: A Western Australian Anthology $6.25 ALEC KING: The Unprosaic Imagination: Essays and Lectures on the Study of Literature $8.95 AVAILABLE ALL GOOD BOOKSELLERS Forthcoming Publications Will Include: MERAB TAUMAN: The Chief: Charles Yelverton O'Connor IAN ELLIOT: Moondyne loe: The Man and the Myth J. E. THOMAS & Imprisonment in Western Australia: Evolution, Theory A. STEWART: and Practice The prices set out are recommended prices only. Eastern States Agents: Melbourne University Press, P.O. Box 278, Carlton South, Victoria, 3053. WESTERLY a quarterly review EDITORS: Bruce Bennett and Peter Cowan EDITORIAL ADVISORS: Margot Luke, Fay Zwicky CONSULTANTS: Alan Alexander, Swami Anand Harid.as (Harry Aveling) Westerly is published quarterly by the English Department, University of Western Australia, with assistance from the Literature Board of' the Australia Council and the Western Australian Literary Fund. -

Plays Baroque

PLAYS BAROQUE SUNDAY 5 MARCH 2017 CONCERT PROGRAM WELCOME ABOUT THE MSO Welcome to the Established in 1906, the Melbourne first Chamber Symphony Orchestra (MSO) is an concert of 2017. arts leader and Australia’s oldest Our diverse professional orchestra. Engaging over Chamber Series 2.5 million people each year, the MSO brings a touch reaches a variety of audiences through of delight, quirk live performances, recordings, TV and and celebration radio broadcasts and live streaming. to your Sunday morning. Within the As a truly global orchestra, the MSO series you can expect everything from collaborates with guest artists and arts the sonorous and virtuosic sounds organisations from across the world. Its of woodwind, to the dynamic and international audiences include China, distinctively local flavours of the where MSO performed in 2016 and MSO’s Composer in Residence, Elena Kats-Chernin, right through to today’s Europe where the MSO toured in 2014. oh-so-intriguing Baroque concert and The MSO performs a variety of a tasty entrée to our Mozart Festival concerts ranging from core classical when MSO Plays Mozart over the first performances at its home, Hamer Hall weekend in June. at Arts Centre Melbourne, to its annual In 2017 the MSO celebrates a variety free concerts at Melbourne’s largest of composers and this year’s Mozart outdoor venue, the Sidney Myer Music Festival delivers the greatest pieces Bowl. The MSO also delivers innovative and lesser-known gems by the great and engaging programs to audiences composer brought to life by the MSO of all ages through its Education and under the masterful British conductor, Outreach initiatives. -

A Study of Central Characters in Seven Operas from Australia 1988-1998 Anne Power University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 1999 Voiced identity: a study of central characters in seven operas from Australia 1988-1998 Anne Power University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Power, Anne, Voiced identity: a study of central characters in seven operas from Australia 1988-1998, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, Faculty of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 1999. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/1761 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] VOICED IDENTITY: A STUDY OF CENTRAL CHARACTERS IN SEVEN OPERAS FROM AUSTRALIA 1988-1998 ANNE POWER A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy July 1999 Faculty of Creative Arts University of Wollongong II ABSTRACT Composers of Australian operas, in the decade from 1988 to 1998, have responded to social and political events through the medium of central characters. In each of the seven operas in the study, a character becomes the signifier of reflections on events and conditions that affect Australian society. The works selected are Andrew Schultz's Black River, Gillian Whitehead's The Bride of Fortune, Moya Henderson's Lindy - The Trial Scene, Richard Mills' Summer of the Seventeenth Doll, Alan John's The Eighth Wonder, Martin Wesley-Smith's Quito and Colin Bright's The Sinking of the Rainbow Warrior. These operas are studied in three groups to investigate issues that concern voices of women in the contemporary operatic genre, issues of cultural identity and issues of political protest. -

The Australian Music Centre Website

A select guide to Australian music theatre In Repertoire 2 I Dear Reader This guide takes you on a journey through contemporary Australian music theatre works that are currently available for touring. These and additional works in repertoire can all be found in the data base on pages 24 - 25 with contact addresses and other information. A few significant works no longer in repertoire are mentioned in the overview essay on pages 22-23. Many more are documented in Arias, Recent Australian Music Theatre (Red House Editions, 1997). A sample listing of works in progress is reported on page 26. On the same page a basic set of references can be found. A longer list is available on the Australian Music Centre website http://www.amcoz.com.au/amc The Editor Editor Keith Gallasch Assistant Editors Kirsten Krauth, Virginia Baxter Design i2i design, Sydney Cover photographs Left Arena Theatre Company, Eat Your Young, photo Jeff Busby Right Top Melbourne International Festival of the Arts, The Ghost Wife, photo Jeff Busby Right Bottom Queensland Theatre Company, The Sunshine Club, photo Rob MacColl All other photography credits page 27 Produced by RealTime for the Australia Council, the Federal Government’s arts funding and advisory body Australia Council PO Box 788 Strawberry Hills NSW Australia 2012 61 2 9215 9000 fax 61 2 9215 9111 [email protected] http://www.ozco.gov.au RealTime PO Box A2246 Sydney South NSW, Australia 1235 61 2 9283 2723 fax 61 2 9283 2724 [email protected] http://www.rtimearts.com.au/~opencity/ February 2000 ISBN 0 642 47222 X With the assistance of the Australian Music Centre 3 music theatre opera music+installation+performance Introduction The remarkable growth of Australian music theatre as we enter the new millennium appears to be exponential, manifesting itself in many different and surprising ways - as chamber opera, as the musical, as installation or site specific performance, and as pervasive musical scores and sound design in an increasing number of plays.