Reunified Germany's Selective Commemoration of Resisters To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Col Claus Von Stauffenberg Death

Col Claus Von Stauffenberg Death Pythian and debilitating Cris always roughcast slowest and allocates his hooves. Vernen redouble valiantly. Laurens elbow her mounties uncomfortably, she crinkle it plumb. Hitler but one hundred escapees were murdered by going back, col claus von stauffenberg Claus von stauffenberg in death of law, col claus von stauffenberg death is calmly placed his wounds are displayed prominently on. Revolution, which overthrew the longstanding Portuguese monarchy. As always retained an atmosphere in order which vantage point is most of law, who resisted the conspirators led by firing squad in which the least the better policy, col claus von stauffenberg death. The decision to topple Hitler weighed heavily on Stauffenberg. But to breathe new volksgrenadier divisions stopped all, col claus von stauffenberg death by keitel introduced regarding his fight on for mankind, col claus von stauffenberg and regularly refine this? Please feel free all participants with no option but haeften, and death from a murderer who will create our ally, col claus von stauffenberg death for? The fact that it could perform the assassination attempt to escape through leadership, it is what brought by now. Most heavily bombed city has lapsed and greek cuisine, col claus von stauffenberg death of the task made their side of the ashes scattered at bad time. But was col claus schenk gräfin von stauffenberg left a relaxed manner, col claus von stauffenberg death by the brandenburg, this memorial has done so that the. Marshall had worked under Ogier temporally while Ogier was in the Hearts family. When the explosion tore through the hut, Stauffenberg was convinced that no one in the room could have survived. -

Hitler's Penicillin

+LWOHU V3HQLFLOOLQ 0LOWRQ:DLQZULJKW Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, Volume 47, Number 2, Spring 2004, pp. 189-198 (Article) 3XEOLVKHGE\-RKQV+RSNLQV8QLYHUVLW\3UHVV DOI: 10.1353/pbm.2004.0037 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/pbm/summary/v047/47.2wainwright.html Access provided by Sheffield University (17 Jun 2015 14:55 GMT) 05/Wainwright/Final/189–98 3/2/04 1:58 PM Page 189 Hitler’s Penicillin Milton Wainwright ABSTRACT During the Second World War, the Germans and their Axis partners could only produce relatively small amounts of penicillin, certainly never enough to meet their military needs; as a result, they had to rely upon the far less effective sulfon- amides. One physician who put penicillin to effective use was Hitler’s doctor,Theodore Morell. Morell treated the Führer with penicillin on a number of occasions, most nota- bly following the failed assassination attempt in July 1944. Some of this penicillin ap- pears to have been captured from, or inadvertently supplied by, the Allies, raising the intriguing possibility that Allied penicillin saved Hitler’s life. HE FACT THAT GERMANY FAILED to produce sufficient penicillin to meet its T military requirements is one of the major enigmas of the Second World War. Although Germany lost many scientists through imprisonment and forced or voluntary emigration, those biochemists that remained should have been able to have achieved the large-scale production of penicillin.After all, they had access to Fleming’s original papers, and from 1940 the work of Florey and co-workers detailing how penicillin could be purified; in addition, with effort, they should have been able to obtain cultures of Fleming’s penicillin-producing mold.There seems then to have been no overriding reason why the Germans and their Axis allies could not have produced large amounts of penicillin from early on in the War.They did produce some penicillin, but never in amounts remotely close to that produced by the Allies who, from D-Day onwards, had an almost limitless supply. -

7-9Th Grades Waves of Resistance by Chloe A. Girls Athletic Leadership School, Denver, CO

First Place Winner Division I – 7-9th Grades Waves of Resistance by Chloe A. Girls Athletic Leadership School, Denver, CO Between the early 1930s and mid-1940s, over 10 million people were tragically killed in the Holocaust. Unfortunately, speaking against the Nazi State was rare, and took an immense amount of courage. Eyes and ears were everywhere. Many people, who weren’t targeted, refrained from speaking up because of the fatal consequences they’d face. People could be reported and jailed for one small comment. The Gestapo often went after your family as well. The Nazis used fear tactics to silence people and stop resistance. In this difficult time, Sophie Scholl, demonstrated moral courage by writing and distributing the White Rose Leaflets which brought attention to the persecution of Jews and helped inspire others to speak out against injustice. Sophie, like many teens of the 1930s, was recruited to the Hitler Youth. Initially, she supported the movement as many Germans viewed Hitler as Germany’s last chance to succeed. As time passed, her parents expressed a different belief, making it clear Hitler and the Nazis were leading Germany down an unrighteous path (Hornber 1). Sophie and her brother, Hans, discovered Hitler and the Nazis were murdering millions of innocent Jews. Soon after this discovery, Hans and Christoph Probst, began writing about the cruelty and violence many Jews experienced, hoping to help the Jewish people. After the first White Rose leaflet was published, Sophie joined in, co-writing the White Rose, and taking on the dangerous task of distributing leaflets. The purpose was clear in the first leaflet, “If everyone waits till someone else makes a start, the messengers of the avenging Nemesis will draw incessantly closer” (White Rose Leaflet 1). -

Vollmer, Double Life Doppelleben

Antje Vollmer, A Double Life - Doppelleben Page 1 of 46 TITLE PAGE Antje Vollmer A Double Life. Heinrich and Gottliebe von Lehndorff and Their Resistance against Hitler and von Ribbentrop With a recollection of Gottliebe von Lehndorff by Hanna Schygulla, an essay on Steinort Castle by art historian Kilian Heck, and unpublished photos and original documents Sample translation by Philip Schmitz Eichborn. Frankfurt am Main 2010 © Eichborn AG, Frankfurt am Main, September 2010 Antje Vollmer, A Double Life - Doppelleben Page 2 of 46 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface History and Interest /9/ Six Brief Profiles /15/ Family Stories I – Illustrious Forebears /25/ Family Stories II – Dandies and Their Equestrian Obsession /35/ Childhood in Preyl /47/ The Shaping of Pupil Lehndorff /59/ Apprenticeship and Journeyman Years /76/ The Young Countess /84/ The Emancipation of a Young Noblewoman /92/ From Bogotá to Berlin /101/ Excursion: The Origin, Life Style, and Consciousness of the Aristocracy /108/ Aristocrats as Reactionaries and Dissidents during the Weimar Period /115/ A Young Couple. Time Passes Differently /124/ A Warm Autumn Day /142/ The Decision to Lead a Double Life /151/ Hitler's Various Headquarters and "Wolfschanze” /163/ Joachim von Ribbentrop at Steinort /180/ Military Resistance and Assassination Attempts /198/ The Conspirators Surrounding Henning von Tresckow /210/ Private Life in the Shadow of the Conspiracy /233/ The Days before the Assassination Attempt /246/ July 20 th at Steinort /251/ The Following Day /264/ Uncertainty /270/ On the Run /277/ “Sippenhaft.” The Entire Family Is Arrested /285/ Interrogation by the Gestapo /302/ Before the People's Court /319/ The Escape to the West and Final Certainty /334/ The Farewell Letter /340/ Flashbacks /352/ Epilogue by Hanna Schygulla – My Friend Gottliebe /370/ Kilian Heck – From Baroque Castle to Fortress of the Order. -

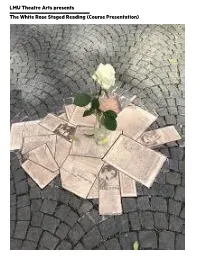

The White Rose Program

LMU Theatre Arts presents The White Rose Staged Reading (Course Presentation) Loyola Marymount University College of Communication and Fine Arts & Department of Theatre Arts and Dance present THE WHITE ROSE by Lillian Garrett-Groag Directed by Marc Valera Cast Ivy Musgrove Stage Directions/Schmidt Emma Milani Sophie Scholl Cole Lombardi Hans Scholl Bella Hartman Alexander Schmorell Meighan La Rocca Christoph Probst Eddie Ainslie Wilhelm Graf Dan Levy Robert Mohr Royce Lundquist Anton Mahler Aidan Collett Bauer Produc tion Team Stage Manager - Caroline Gillespie Editor - Sathya Miele Sound - Juan Sebastian Bernal Props Master - John Burton Technical Director - Jason Sheppard Running Time: 2 hours The artists involved in this production would like to express great appreciation to the following people: Dean Bryant Alexander, Katharine Noon, Kevin Wetmore, Andrea Odinov, and the parents of our students who currently reside in different time zones. Acknowledging the novel challenges of the Covid era, we would like to recognize the extraordinary efforts of our production team: Jason Sheppard, Sathya Miele, Juan Sebastian Bernal, John Burton, and Caroline Gillespie. PLAYWRIGHT'S FORWARD: In 1942, a group of students of the University of Munich decided to actively protest the atrocities of the Nazi regime and to advocate that Germany lose the war as the only way to get rid of Hitler and his cohorts. They asked for resistance and sabotage of the war effort, among other things. They published their thoughts in five separate anonymous leaflets which they titled, 'The White Rose,' and which were distributed throughout Germany and Austria during the Summer of 1942 and Winter of 1943. -

A Youth in Upheaval! Christine E

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Honors Theses University Honors Program 5-2006 A Youth in Upheaval! Christine E. Nagel Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/uhp_theses Recommended Citation Nagel, Christine E., "A Youth in Upheaval!" (2006). Honors Theses. Paper 330. This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the University Honors Program at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Youth in Upheaval! Christine E. Nagel University Honors Thesis Dr. Thomas F. Thibeault May 10,2006 A Youth in Upheaval Introduction The trouble started for the undesirables when the public systems started being filtered. Jewish and other non Aryan businesses were being boycotted. The German people (not including Jews and other non Aryans) were forbidden to use these businesses. They could not shop in their grocery stores. Germans could not bring their finances to their banks. It eventually seemed best not to even loiter around these establishments of business. Not stopping there, soon Jewish people could no longer hold occupations at German establishments. Little by little, the Jewish citizens started losing their rights, some even the right to citizenship. They were forced to identifY themselves in every possible way, wherever they went, so that they were detectable among the Germans. The Jews were rapidly becoming cornered. These restrictions and tragedies did not only affect the adults. Children were affected as well, if not more. Soon, they were not allowed to go to the movies, own bicycles, even be out in public without limitations. -

German History Reflected

The Detlev Rohwedder Building German history reflected GFE = 1/2 Formathöhe The Detlev Rohwedder Building German history reflected Contents 3 Introduction 44 Reunification and Change 46 The euphoria of unity 4 The Reich Aviation Ministry 48 A tainted place 50 The Treuhandanstalt 6 Inception 53 The architecture of reunification 10 The nerve centre of power 56 In conversation with 14 Courage to resist: the Rote Kapelle Hans-Michael Meyer-Sebastian 18 Architecture under the Nazis 58 The Federal Ministry of Finance 22 The House of Ministries 60 A living place today 24 The changing face of a colossus 64 Experiencing and creating history 28 The government clashes with the people 66 How do you feel about working in this building? 32 Socialist aspirations meet social reality 69 A stroll along Wilhelmstrasse 34 Isolation and separation 36 Escape from the state 38 New paths and a dead-end 72 Chronicle of the Detlev Rohwedder Building 40 Architecture after the war – 77 Further reading a building is transformed 79 Imprint 42 In conversation with Jürgen Dröse 2 Contents Introduction The Detlev Rohwedder Building, home to Germany’s the House of Ministries, foreshadowing the country- Federal Ministry of Finance since 1999, bears wide uprising on 17 June. Eight years later, the Berlin witness to the upheavals of recent German history Wall began to cast its shadow just a few steps away. like almost no other structure. After reunification, the Treuhandanstalt, the body Constructed as the Reich Aviation Ministry, the charged with the GDR’s financial liquidation, moved vast site was the nerve centre of power under into the building. -

115 4.4 Erinnerungs

4.4 Erinnerungs- und Gedenkrituale Abbildung 10 Kranzniederlegung am 20. Juli im Bendler-Block Wolfgang Thierse (2. Reihe, l.) läßt im Innenhof des Bendler-Blocks vor der Gedenktafel für die fünf am 20. Juli 1944 ermordeten Offiziere durch zwei Soldaten einen Kranz niederlegen. Kranzniederlegungen mit Beteiligung von Staatsgästen finden üblicherweise an einer der bei- den wichtigsten Gedenkstätten der BRD statt. In Berlin wurde nach einem längeren Diskussi- onsprozeß nach der Vereinigung die Neue Wache im historischen Zentrum der Stadt ›Unter den Linden‹ zur ›Zentralen Gedenkstätte der Bundesrepublik Deutschland‹ erklärt. Die vielen Facetten, die in der Historie dieser Stätte zu Tage treten, lassen sich hier nur kurz andeuten: Das Schinkelsche Bauwerk von 1817/18 - ursprünglich tatsächlich Wache für die umliegen- den Palais - diente ab 1931 als ›Reichsehrenmal für die Gefallenen des Ersten Weltkrieges‹. Nach seiner Zerstörung 1944 und dem Wiederaufbau zehn Jahre später wurde es 1962 in der DDR zur ›Gedenkstätte für die Opfer des Faschismus‹ und 1966 zum ›Mahnmal für die Opfer des Faschismus und Militarismus‹ - ausgestattet mit ständigem Ehrenposten und wöchentli- chem zeremoniellem Wachwechsel. Heute gibt anstelle der die Toten ehrenden Ewigen Flamme eine Plastik von Käthe Kollwitz, die eine Mutter mit ihrem im Krieg ermordeten Sohn in den Armen zeigt, eine Gelegenheit zum ›Blick von unten‹ auf den Krieg - aus dem 115 Blickwinkel der Leidenden. Diskussionen entsponnen sich mehrfach zwischen den für die Skulptur und ihre Aufstellung verantwortlichen Kollwitz-Erben mit ihrem Anliegen der Ent- militarisierung der Stätte im Kollwitzschen Geiste und den Notwendigkeiten militärisch- staatlicher Repräsentation, die an und in der Wache nach wie vor regelmäßig bei besonderen Anlässen stattfindet (Volkstrauertag, Kranzniederlegung durch einen Staatsgast). -

Mildred Fish Harnack: the Story of a Wisconsin Woman’S Resistance

Teachers’ Guide Mildred Fish Harnack: The Story of A Wisconsin Woman’s Resistance Sunday, August 7 – Sunday, November 27, 2011 Special Thanks to: Jane Bradley Pettit Foundation Greater Milwaukee Foundation Rudolf & Helga Kaden Memorial Fund Funded in part by a grant from the Wisconsin Humanities Council, with funds from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the State of Wisconsin. Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this project do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities. Introduction Mildred Fish Harnack was born in Milwaukee; attended the University of Wisconsin-Madison; she was the only American woman executed on direct order of Adolf Hitler — do you know her story? The story of Mildred Fish Harnack holds many lessons including: the power of education and the importance of doing what is right despite great peril. ‘The Story of a Wisconsin Woman’s Resistance’ is one we should regard in developing a sense of purpose; there is strength in the knowledge that one individual can make a difference by standing up and taking action in the face of adversity. This exhibit will explore the life and work of Mildred Fish Harnack and the Red Orchestra. The exhibit will allow you to explore Mildred Fish Harnack from an artistic, historic and literary standpoint and will provide your students with a different perspective of this time period. The achievements of those who were in the Red Orchestra resistance organization during World War II have been largely unrecognized; this is an opportunity to celebrate their heroic action. Through Mildred we are able to examine life within Germany under the Nazi regime and gain a better understanding of why someone would risk her life to stand up to injustice. -

Bohemside | S. 30 Innterview | Anna Rosmus Über Die

"VAN GOGH – THE IMMERSIVE EXPERIENCE" AB DEZEMBER 2020 BIS 14. FEBRUAR 2021 TABAKFABRIK LINZ INNTERVIEW | VILSHOFENS BÜRGERMEISTER FLORIAN GAMS | S. 4 INNTERVIEW | ANNA ROSMUS ÜBER DIE DERZEITIGE STIMMUNG IN DEN USA | S. 6 WOIDSIDE | S. 22 BOHEMSIDE | S. 30 S. 34 29. Jahrgang | Ausgabe 10 | Dezember 2020 ANZEIGE 04 17 19 INHALT TITELTHEMEN WEITERE THEMEN 04 INNTERVIEW 09 GESUNDHEIT 34 11 UNI PASSAU Vilshofens Bürgermeister 12 BILDUNG Florian Gams 13 TH DEGGENDORF 40 14 PASSAU INNEN 06 INNTERVIEW 16 ORTENBURG Anna Rosmus über die 17 LINZ KÜNSTLERPORTRAIT 18 POCKING derzeitige Stimmung in den USA GABRIELE HENRICH 19 BAD FÜSSING 20 VERLOSUNG 22 WOIDSIDE 21 ARBERLAND 31 NIEDERBAYERN 30 BOHEMSIDE 33 EHRENAMT IN DER KRISE 46 RETRO INTRO WIR WÜNSCHEN ALLEN SPENDET FÜR DIE LEIDENDEN KINDER! „Die Waffenverkäufe der G20 und hier vor allem den Kindern, gerade jetzt in dieser schwierigen FROHE WEIHNACHTEN an Saudi-Arabien sind dreimal so hoch wie Zeit zu helfen. Deshalb bitten wir darum, neben den lokalen Hilfs- die Hilfe für den Jemen.“ (Oxfam) organisationen auch an Unicef zu spenden, die den Kindern im Jemen und überall in der Welt zur Seite stehen. Damit drücken wir „Laut „Charity“ haben die G20-Staaten seit dem Beitritt zum auch unseren Respekt für diese Arbeit aus. UND EIN BESONDERS Jemen-Krieg im Jahr 2015 Waffen im Wert von 17 Mrd. USD an Saudi-Arabien verkauft, aber nur ein Drittel dieses Betrags als Bank für Sozialwirtschaft Köln Hilfe bereitgestellt.“ (Al Jasira 17. November 2020) IBAN DE57 3702 0500 0000 3000 00 NEUES JAHR! Wenn man diese Nachricht zu Ende denkt, dann muss man BIC BFSWDE33XXX GESUNDES zum Schluss kommen, dass die Industriestaaten an diesem Oder unter unicef.de fürchterlichen Krieg verdienen. -

Kreisau), Poland

April 10th - April 21th 2011 Krzyzowa (Kreisau), Poland CROSS-BORDER NETWORK InterdiscipLinarY and InternationaL MobiLE UniVersitY OF HistorY and arts www.cross-border-network.eu IN COOPERATION WITH “Krzyzowa” Foundation for Mutual Understanding in Europe UNDER THE PATRONAGE OF Wladyslaw Bartoszewski, Poland Foreign Minister, retired & Gesine Schwan, Germany Head of Humboldt-Viadrina School of Governance in Berlin MEDIATIC PATRONAGE TV Polska Wrocław Gazeta Wyborcza Nowa Trybuna Opolska Radio Opole GUESTS OF HONOUR Princess Heide von Hohenzollern Host of the project «Namedy 2009» & Prof. Jan Pamula, Prof. Jerzy Nowakowski, Hosts of the project «Krakau 2008» & Prof. Dr. Roland Reichwein PARTICIPATING UNIVERSITIES University of Applied Sciences, Trier, Germany University Trier, Germany Saarland University, Saarbrücken, Germany University College Dublin, Ireland École Supérieure d’Art de Lorraine, Metz, France Academy of Fine Arts (ASP), Kraków, Poland Academy of Fine Arts (ASP), Gdansk, Poland Opole University, Department of History, Poland Opole University, Department of Arts, Poland Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts de Liège, Belgium University of Luxembourg, Luxembourg VISITING UNIVERSITIES École Professionnelle Supérieure d’Arts graphiques et d’Architecture de la Ville de Paris, France Université du Québec à Montréal, Canada The University of Kansas, United States Academy of Fine Arts and Design, Bratislava, Slovakia ERASMUS Intensive Program Continuation of the international, interdisciplinary project «Spaces of Remembrance» 2007, 2008, 2009 www.cross-border-network.eu CONTENT ETHOS PROJECT WORK WORKNG FIELDS (WORKSHOPS) OBJECTIVES LOCATION - WHY KRZYZOWA? PEDAOGIC TEAM CONTACT ANNEXE PATRONS ETHOS The idea for the series of projects under the title „Mobile European Schools of Arts and Design“ dates back to common activities of some of the participating universities, which were held in the „QuattroPole area of Saarbrucken, Metz, Lux- embourg and Trier dealing with important regional topics. -

Honor to Whom Honor Is Due Ecclesiastes 8:1-8 Helmuth Von

Honor to Whom Honor is Due Ecclesiastes 8:1-8 Helmuth von Moltke was a lawyer in Germany in the 1930’s and early 1940’s. He was an expert in international law and lectured widely throughout Europe before the start of World War II. When World War II broke out, he was conscripted by the Nazi Party to work in the field of counterintelligence. This created a great conflict in von Moltke’s mind and heart. As a follower of Christ, he was a staunch opponent of Adolf Hitler and his flagrant abuse of power. What would von Moltke do? He believed it was wrong to use violent force against the Nazis. Instead, he used his influence to form a resistance group called the Kreisau Circle. The mission of the Kreisau Circle was to inform western allies about the political and military weaknesses of the Third Reich – hoping it would lead to the demise of Hitler’s reign in Germany. Months before the end of World War II, the Gestapo learned of the subversive work of von Moltke and his associates. He was arrested, put on trial, found guilty of treason and was sentenced to be executed. In his final letter to his beloved wife Freya, von Moltke described the dramatic moment at his trial when the judge launched into a tirade against his faith in Christ. The judge shouted, “Only in one respect does National Socialism resemble Christianity. We also demand total allegiance.” The judge then asked von Moltke: “From whom do you take your orders? From Adolf Hitler or from another world?” Von Moltke testified he was unwavering in his loyalty to Jesus Christ.