The Mountains of Central Tibet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Making the State on the Sino-Tibetan Frontier: Chinese Expansion and Local Power in Batang, 1842-1939

Making the State on the Sino-Tibetan Frontier: Chinese Expansion and Local Power in Batang, 1842-1939 William M. Coleman, IV Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Columbia University 2014 © 2013 William M. Coleman, IV All rights reserved Abstract Making the State on the Sino-Tibetan Frontier: Chinese Expansion and Local Power in Batang, 1842-1939 William M. Coleman, IV This dissertation analyzes the process of state building by Qing imperial representatives and Republican state officials in Batang, a predominantly ethnic Tibetan region located in southwestern Sichuan Province. Utilizing Chinese provincial and national level archival materials and Tibetan language works, as well as French and American missionary records and publications, it explores how Chinese state expansion evolved in response to local power and has three primary arguments. First, by the mid-nineteenth century, Batang had developed an identifiable structure of local governance in which native chieftains, monastic leaders, and imperial officials shared power and successfully fostered peace in the region for over a century. Second, the arrival of French missionaries in Batang precipitated a gradual expansion of imperial authority in the region, culminating in radical Qing military intervention that permanently altered local understandings of power. While short-lived, centrally-mandated reforms initiated soon thereafter further integrated Batang into the Qing Empire, thereby -

17-Point Agreement of 1951 by Song Liming

FACTS ABOUT THE 17-POINT “Agreement’’ Between Tibet and China Dharamsala, 22 May 22 DIIR PUBLICATIONS The signed articles in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the Central Tibetan Administration. This report is compiled and published by the Department of Information and International Relations, Central Tibetan Administration, Gangchen Kyishong, Dharamsala 176 215, H. P., INDIA Email: [email protected] Website: www.tibet.net and ww.tibet.com CONTENTS Part One—Historical Facts 17-point “Agreement”: The full story as revealed by the Tibetans and Chinese who were involved Part Two—Scholars’ Viewpoint Reflections on the 17-point Agreement of 1951 by Song Liming The “17-point Agreement”: Context and Consequences by Claude Arpi The Relevance of the 17-point Agreement Today by Michael van Walt van Praag Tibetan Tragedy Began with a Farce by Cao Changqing Appendix The Text of the 17-point Agreement along with the reproduction of the original Tibetan document as released by the Chinese government His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s Press Statements on the “Agreement” FORWARD 23 May 2001 marks the 50th anniversary of the signing of the 17-point Agreement between Tibet and China. This controversial document, forced upon an unwilling but helpless Tibetan government, compelled Tibet to co-exist with a resurgent communist China. The People’s Republic of China will once again flaunt this dubious legal instrument, the only one China signed with a “minority” people, to continue to legitimise its claim on the vast, resource-rich Tibetan tableland. China will use the anniversary to showcase its achievements in Tibet to justify its continued occupation of the Tibetan Plateau. -

De Paris Au Tonkin À Travers Le Tibet Inconnu, Étude D'un Voyage D

Diplôme national de master Domaine - sciences humaines et sociales Mention - histoire civilisation patrimoine Parcours - cultures de l’écrit et de l’image De Paris au Tonkin à travers le Tibet inconnu, étude d’un voyage d’exploration en Asie centrale à la fin du XIXe siècle par l’explorateur Gabriel Bonvalot. Mémoire 2 professionnel / Août 2019 Août / professionnel 2 Mémoire Duranseaud Maxime Sous la direction de Philippe Martin Professeur d’histoire moderne – Université Lyon 2 Remerciements Merci à Mr Philippe Martin d’avoir accepté de diriger ce mémoire et de m’avoir guidé dans ma réflexion pendant ces deux années de master. Merci aussi à Mme Cristina Cramerotti et au personnel de la bibliothèque du Musée des Arts Asiatiques Guimet pour m’avoir permis de passer quatre mois de stage particulièrement agréables et instructifs, mais aussi d’avoir largement facilité mes recherches documentaires notamment grâce à un accès privilégié aux ouvrages que renferment les magasins de la bibliothèque. Sans cela, il aurait été bien plus compliqué pour moi de réaliser ce mémoire. Encore une fois merci beaucoup. 2 Résumé : Il s’agit d’une étude du voyage de l’explorateur Gabriel Bonvalot, réalisé entre 1889 et 1890 en Asie Centrale, plus précisément dans la région du Xinjiang Chinois et du Tibet, dans un périple qui le fera traverser le Continent Eurasiatique depuis le nord-est jusqu’à l’extrême sud-ouest. Le récit qui résultera de ce voyage : « De Paris au Tonkin à travers le Tibet inconnu » raconte le parcours de l’expédition et nous servira ici de source principale. -

Gabriel Bonvalot, Explorateur (1853-1933)

EXPLORATION DE L’ASIE par Laurence Doizelet et Jean-Louis Humbert Gabriel Bonvalot, explorateur (1853-1933) Né dans l’Aube, Pierre-Gabriel Bonvalot, grand races ». Il parcourt ainsi l’Asie centrale de 1880 à 1882, voyageur et découvreur de routes, patriote, accompagné de Guillaume Capus, docteur ès-sciences écrivain à la fois conteur, géographe, reporter, et naturaliste. Il visite les grandes villes du Turkestan historien… a été aussi maire de Brienne-le- et découvre les ruines de Chahri-Samane. Au retour, il Château. Des expositions lui furent consacrées : publie deux ouvrages : De Moscou en Bactriane (1884), l’une en 2005 à Brienne, l’autre en 2006 aux De Kohistan à la Caspienne (1885). Archives départementales de l’Aube. En 1885, une deuxième mission entraîne les deux hommes le long de la mer Caspienne. Le peintre champenois Albert Pépin les accompagne et illustre l’expédition. Ils Des pays, un rêve, un homme… traversent le Caucase en direction de la Perse. Après avoir passé l’hiver 1885-1886 à Samarcande, Gabriel Une curiosité précoce pour le monde Bonvalot décide de traverser le Pamir ; il est le premier Européen qui ose s’aventurer dans ces régions à la saison Gabriel Bonvalot est né le 14 juillet 1853 à Épagne, des tempêtes par des températures de moins 25 °C. Il village situé aux alentours de Brienne-le-Château. Ses y parvient et ouvre une voie terrestre vers les Indes, parents Pierre Bonvalot, employé des contributions exploit qui a plus de retentissement à Saint-Pétersbourg indirectes, et Félicie Desjardins veillent à lui donner une qu’à Paris. -

Introduction

TIBET UNDER COMMUNIST CHINA Introduction Tibet Under Communist China—50 Years is a detailed and comprehensive examination of the various strands of Beijing’s imperial strategy to cement its rule over one of the restive outposts of communist China’s sprawling empire. It sheds new light on the over-arching geopolitical impulses that drive China to initiate new, and sometimes contradictory, policies in Tibet, only to reverse them in a decade or two, all in the attempt to ensure that one loose brick does not bring the whole imperial edifice crumbling down. In this respect, Tibet Under Communist China—50 Years will be a new resource to both China specialists, governments, businessmen and other interested parties in their understanding of the world’s largest surviving empire, which also happens to be its biggest market with a booming economy and an insatiable appetite for energy and other resources. As long as China remained a one-party dictatorship sticking to a socialist pattern of development, the natural resources of the so-called minority peoples were fairly safe. Now with China’s conversion to a market economy with one of the highest annual growth rate in the world, the abundant natural resources on the fringes of the empire are rapidly exploited to fuel the dynamic development of the centre. The change of the Chinese attitude to its imperial fringes, from mere imperial outposts to resource-rich colonies to supply the raw material to maintain a dynamic economy, should be of enormous concern to the so-called minorities who inhabit these vast regions endowed with rich natural resources. -

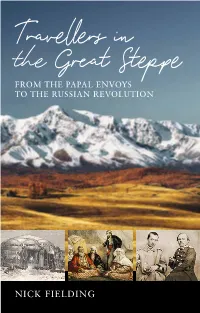

Nick Fielding

Travellers in the Great Steppe FROM THE PAPAL ENVOYS TO THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION NICK FIELDING “In writing this book I have tried to explain some of the historical events that have affected those living in the Great Steppe – not an easy task, as there is little study of this subject in the English language. And the disputes between the Russians and their neighbours and between the Bashkirs, the Kazakhs, the Turkomans, the Kyrgyz and the Kalmyks – not to mention the Djungars, the Dungans, the Nogai, the Mongols, the Uighurs and countless others – means that this is not a subject for the faint-hearted. Nonetheless, I hope that the writings referred to in this book have been put into the right historical context. The reasons why outsiders travelled to the Great Steppe varied over time and in themselves provide a different kind of history. Some of these travellers, particularly the women, have been forgotten by modern readers. Hopefully this book will stimulate you the reader to track down some of the long- forgotten classics mentioned within. Personally, I do not think the steppe culture described so vividly by travellers in these pages will ever fully disappear. The steppe is truly vast and can swallow whole cities with ease. Landscape has a close relationship with culture – and the former usually dominates the latter. Whatever happens, it will be many years before the Great Steppe finally gives up all its secrets. This book aims to provide just a glimpse of some of them.” From the author’s introduction. TRAVELLERS IN THE GREAT STEPPE For my fair Rosamund TRAVELLERS IN THE GREAT STEPPE From the Papal Envoys to the Russian Revolution NICK FIELDING SIGNAL BOOKS . -

The Geladaindong Massif, Which Sits Roughly in The

348 T HE A MERICAN A LPINE J OURNAL , 2009 C LIMBS AND E XPEDITIONS : C HINA 349 The Geladaindong massif, which sits China roughly in the middle of the Tangula XINJIANG PROVINCE Shan, is 50km long (north-south) and Muzart Glacier, ascents and exploration. 20km wide (west-east). The highest The British–New Zealand expedition point, Geladaindong, is surrounded by of Paul Knott, Guy McKinnon, and more than 20 peaks higher than Bruce Normand gained a permit for 6,000m, most still unclimbed. French Xuelian Feng (6,628m), the dominant explorer Gabriel Bonvalot came to these peak in the eastern sector of the Chi - mountains at the source of the Yangtze nese Central Tien Shan, and one of few River (Chang Jiang) in 1890 and mountains in this region to have been referred to them as the Dupleix Range. climbed (by Japanese on their fourth attempt). The three acclimatized to altitudes of 5,400m Japanese first tried to negotiate a permit The east face of Peak 6,543m in the Geladaindong Massif. The on peaks on the north side of Muzart basin, after which Normand and McKinnon made a bid in 1982, but not until 1985 were they peak was climbed in 2007 by a Japanese expedition via the on the Xuelian side. After climbing questionable snow and reasonable ice slopes, they reached able to access the range and make the broad col on the right and the north-northwest ridge above. a point of listed height 6,332m, well east of the main summit of Xuelian Feng. An article by first ascent of Geladaindong, by the Courtesy of Tamotsu Nakamura and the Japanese Alpine News Knott and Normand on this little-known area extending east and south from 7,439m Pik Pobe - northwest ridge, approaching from the northeast. -

Ladakh at the Cross-Road During 19Th and 20Th Century

Ladakh at the Cross-road During 19th and 20th Century Rinchen Dolma Abstract In most of the historical records of the Silk Route there is reference to Ladakh, and many viewed it as an extension of it. Ladakh acted as an important gateway in the exchange of men, material and ideas through the ages. Leh the capital of Ladakh was the meeting point for traders from South Asia and from Central Asia. Ladakh as a conduit between India and Central Asia played an important role in the political, commercial and cultural domains both in the ancient and medieval times. Due to its geographical proximity to Central Asia and linkages to old Silk-Route, Ladakh became the transit emporium in the bilateral Indo-Central Asian trade. The present paper is intended to study the glimpses of historical links of India and Central Asia through Ladakh along with the present geopolitical and geostrategic location of the region. Moreover, the revival of ancient routes of Ladakh and its benefits has also been discussed. Keywords Ladakh, Central Asia, Silk-Road, Buddhism, Culture, Trade and Security. Introduction Ladakh has always played a fundamental role since early times because of its geographical contiguity with Eastern Turkistan and has provided a space for overland trade routes and also for the existence of socio- cultural links between different regions. The regions of Ladakh and Kashmir Valley had links with the regions of Central Asia stretching back to the nineteenth and the twentith centuries. Today families who had traditional trade links in Leh narrate the trade flows between Leh and Yarkand well into the middle of the last century. -

Iranian Young Scientist to Receive Grant

Art & Culture JUNE 24, 2015 3 This Day in History Iranian Young Scientist to (June 24) Today is Wednesday; 3rd of the Iranian month of Tir 1394 solar hijri; corresponding to 7th of the Islamic month of Ramadhan 1436 lunar hijri; and June 24, 2015, of the Christian Gregorian Calendar. 1437 lunar years ago, on this day in the second year prior to Hijra, Abu-Taleb, the father of Imam Receive grant Ali (AS) and the uncle and protector of Prophet Mohammad (SAWA), passed away in Mecca. On the death of his father Abdul-Muttaleb, he and his wife, Fatema bint Asad, had taken charge of the PARIS ( IRNA) – Iranian young scientist Dr. Mehdi Mohammadi was selected to receive the support of the Green 8-year orphan of Abdullah, his deceased brother, and brought up the future Prophet as their own son. Abu Taleb was a staunch monotheist following the creed of his ancestor, Prophet Abraham, and Chemistry for Life project. when God formally appointed his now 40-year old nephew as the Last and Greatest Messenger to The award was created by UNESCO, PhosAgro and the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry mankind, he firmly believed in the message of Islam and protected the Prophet against the taunts and attacks of the pagan Arabs. When the Meccans imposed the social-economic boycott on the Prophet, (IUPAC) to promote the sustainable use and design of chemicals and chemical processes. he took his nephew and the whole neo Muslim community under his protection to the safety of the Some 119 Applicants were evaluated by an international scientific jury composed of renowned scientists repre- gorge outside Mecca which is still called “She’b Abi Taleb” in his honour. -

October 21, 1953 Cable from Zhang Jingwu, 'On Issues of Relations Between China and India in Tibet'

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified October 21, 1953 Cable from Zhang Jingwu, 'On Issues of Relations between China and India in Tibet' Citation: “Cable from Zhang Jingwu, 'On Issues of Relations between China and India in Tibet',” October 21, 1953, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, PRC FMA 105-00032-23, 76-81. Translated by 7Brands. http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/114754 Summary: Zhang Jingwu reports on the Simla Accord and the McMahon line running between India and Tibet, and offers policy recommendations. Credits: This document was made possible with support from the MacArthur Foundation. Original Language: Chinese Contents: English Translation [...] On Issues of Relations between China and India in Tibet To the Ministry of Foreign Affairs: Your correspondence dated 7 October [1953] and the two types of Indian documents have been received. Research shows that the assumption that “India intends to capitalize on this opportunity to have some benefit in Tibet,” as mentioned in your correspondence, is very accurate. Based on the information that we have at hand about Tibet, we still need Indian cooperation in some international issues. However, India is capitalizing on our temporary difficulties in Tibet, particularly our insufficient understanding of imperialist privileges in Tibet and the ideal solution to border disputes, as well as our need for India’s cooperation in various areas, to gain benefits by offering a general solution to the Tibet issue. As a matter of fact, there have always been disputes on some issues, e.g. commercial exchanges and representative offices, because we have always claimed our sovereignty over Tibet. -

Huang Wenbi: Pioneer of Chinese Archaeology in Xinjiang

HUANG WENBI: PIONEER OF CHINESE ARCHAEOLOGY IN XINJIANG Justin M. Jacobs $PHULFDQ8QLYHUVLW\ henever one thinks of the history of the Silk Nikolai Petrovskii, Otani Kozui, Tachibana Zuicho, W Road and of the explorers and archaeologists George Macartney, Clarmont Skrine, Gustav Manner- ZKRÀUVWXQHDUWKHGLWVP\ULDGVRIDQFLHQWWUHDVXUHV heim, and perhaps even Ellsworth Huntington. One a select group of names readily comes to mind: Sven name that is rarely included within such lists, howev- Hedin, Aurel Stein, Albert von Le Coq, and Paul Pel- HULV+XDQJ:HQEL ² >)LJ@WKHÀUVW&KL- liot, to name just a few of the most famous (or infa- nese archaeologist to undertake excavations in Xinji- mous, depending on your perspective). For those ang. An international symposium dedicated entirely scholars who are somewhat more familiar with the to Huangs life and career, held in Urumqi in October history of the expeditions themselves, other explor- 2013 and sponsored by Xinjiang Normal University HUVDQGLQÁXHQWLDOSHUVRQDJHVDUHMXVWDVZHOONQRZQ and the newly established Huang Wenbi Institute FRQVWLWXWHV WKH ÀUVW VLJQLÀFDQW attempt to reassess his legacy. The conference, in which scholars from China, Ja- pan, Europe, and America all participated, was held in tandem with the publication of three substantial collections of articles likely to be of interest to anyone who studies some aspect of the history of the Silk Road in northwestern China. For historians and linguists of the pre-modern era, the most useful volume is likely to be &ROOHFWHG 3DSHUV RQ WKH 'RFXPHQWV 'LVFRYHUHG E\ +XDQJ:HQELLQWKH:HVWHUQ5HJLRQV (Beijing: Kexue chubanshe, 2013), edited by the noted Dunhuang scholar Rong Xinjiang. In his pref- ace, Rong observes that scholars have long referred to repositories of manuscripts and artifacts in London or Paris as the Stein collection or the Pelliot collec- tion, but that no one ever refers to the Huang Wenbi collection, despite its comparable size. -

Silk Roads in History by Daniel C

The Silk Roads in History by daniel c. waugh here is an endless popular fascination with cultures and peoples, about whose identities we still know too the “Silk Roads,” the historic routes of eco- little. Many of the exchanges documented by archaeological nomic and cultural exchange across Eurasia. research were surely the result of contact between various The phrase in our own time has been used as ethnic or linguistic groups over time. The reader should keep a metaphor for Central Asian oil pipelines, and these qualifications in mind in reviewing the highlights from Tit is common advertising copy for the romantic exoticism of the history which follows. expensive adventure travel. One would think that, in the cen- tury and a third since the German geographer Ferdinand von Richthofen coined the term to describe what for him was a The Beginnings quite specific route of east-west trade some 2,000 years ago, there might be some consensus as to what and when the Silk Among the most exciting archaeological discoveries of the Roads were. Yet, as the Penn Museum exhibition of Silk Road 20th century were the frozen tombs of the nomadic pastoral- artifacts demonstrates, we are still learning about that history, ists who occupied the Altai mountain region around Pazyryk and many aspects of it are subject to vigorous scholarly debate. in southern Siberia in the middle of the 1st millennium BCE. Most today would agree that Richthofen’s original concept These horsemen have been identified with the Scythians who was too limited in that he was concerned first of all about the dominated the steppes from Eastern Europe to Mongolia.