1956 in Hungary and in Canada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

43E Festival International Du Film De La Rochelle Du 26 Juin Au 5 Juillet 2015 Le Puzzle Des Cinémas Du Monde

43e Festival International du Film de La Rochelle du 26 juin au 5 juillet 2015 LE PUZZLE DES CINÉMAS DU MONDE Une fois de plus nous revient l’impossible tâche de synthétiser une édition multiforme, tant par le nombre de films présentés que par les contextes dans lesquels ils ont été conçus. Nous ne pouvons nous résoudre à en sélectionner beaucoup moins, ce n’est pas faute d’essayer, et de toutes manières, un contexte économique plutôt inquiétant nous y contraint ; mais qu’une ou plusieurs pièces essentielles viennent à manquer au puzzle mental dont nous tentons, à l’année, de joindre les pièces irrégulières, et le Festival nous paraîtrait bancal. Finalement, ce qui rassemble tous ces films, qu’ils soient encore matériels ou virtuels (50/50), c’est nous, sélectionneuses au long cours. Nous souhaitons proposer aux spectateurs un panorama généreux de la chose filmique, cohérent, harmonieux, digne, sincère, quoique, la sincérité… Ambitieux aussi car nous aimons plus que tout les cinéastes qui prennent des risques et notre devise secrète pourrait bien être : mieux vaut un bon film raté qu’un mauvais film réussi. Et enfin, il nous plaît que les films se parlent, se rencontrent, s’éclairent les uns les autres et entrent en résonance dans l’esprit du festivalier. En 2015, nous avons procédé à un rééquilibrage géographique vers l’Asie, absente depuis plusieurs éditions de la programmation. Tout d’abord, avec le grand Hou Hsiao-hsien qui en est un digne représentant puisqu’il a tourné non seulement à Taïwan, son île natale mais aussi au Japon, à Hongkong et en Chine. -

DVD Profiler

101 Dalmatians II: Patch's London Adventure Animation Family Comedy2003 74 minG Coll.# 1 C Barry Bostwick, Jason Alexander, The endearing tale of Disney's animated classic '101 Dalmatians' continues in the delightful, all-new movie, '101 Dalmatians II: Patch's London A Martin Short, Bobby Lockwood, Adventure'. It's a fun-filled adventure fresh with irresistible original music and loveable new characters, voiced by Jason Alexander, Martin Short and S Susan Blakeslee, Samuel West, Barry Bostwick. Maurice LaMarche, Jeff Bennett, T D.Jim Kammerud P. Carolyn Bates C. W. Garrett K. SchiffM. Geoff Foster 102 Dalmatians Family 2000 100 min G Coll.# 2 C Eric Idle, Glenn Close, Gerard Get ready for outrageous fun in Disney's '102 Dalmatians'. It's a brand-new, hilarious adventure, starring the audacious Oddball, the spotless A Depardieu, Ioan Gruffudd, Alice Dalmatian puppy on a search for her rightful spots, and Waddlesworth, the wisecracking, delusional macaw who thinks he's a Rottweiler. Barking S Evans, Tim McInnerny, Ben mad, this unlikely duo leads a posse of puppies on a mission to outfox the wildly wicked, ever-scheming Cruella De Vil. Filled with chases, close Crompton, Carol MacReady, Ian calls, hilarious antics and thrilling escapes all the way from London through the streets of Paris - and a Parisian bakery - this adventure-packed tale T D.Kevin Lima P. Edward S. Feldman C. Adrian BiddleW. Dodie SmithM. David Newman 16 Blocks: Widescreen Edition Action Suspense/Thriller Drama 2005 102 min PG-13 Coll.# 390 C Bruce Willis, Mos Def, David From 'Lethal Weapon' director Richard Donner comes "a hard-to-beat thriller" (Gene Shalit, 'Today'/NBC-TV). -

Tricks of the Light

Tricks of the Light: A Study of the Cinematographic Style of the Émigré Cinematographer Eugen Schüfftan Submitted by Tomas Rhys Williams to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Film In October 2011 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature: ………………………………………………………….. 1 Abstract The aim of this thesis is to explore the overlooked technical role of cinematography, by discussing its artistic effects. I intend to examine the career of a single cinematographer, in order to demonstrate whether a dinstinctive cinematographic style may be defined. The task of this thesis is therefore to define that cinematographer’s style and trace its development across the course of a career. The subject that I shall employ in order to achieve this is the émigré cinematographer Eugen Schüfftan, who is perhaps most famous for his invention ‘The Schüfftan Process’ in the 1920s, but who subsequently had a 40 year career acting as a cinematographer. During this time Schüfftan worked throughout Europe and America, shooting films that included Menschen am Sonntag (Robert Siodmak et al, 1929), Le Quai des brumes (Marcel Carné, 1938), Hitler’s Madman (Douglas Sirk, 1942), Les Yeux sans visage (Georges Franju, 1959) and The Hustler (Robert Rossen, 1961). -

Nmscutsgo? Lit Was a Larger Problem Than Just New York Ity; It Is Encountered by Most Older Merican Cities," She Explained

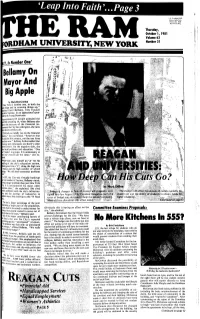

'Leap Into Faith \..Page 3 US PoslagePAID Bronx. New York Permit No. 7608 Non-profit Org. Thursday, October 1,1981 Volume 63 IRPHAM UNIVERSITY, NEW YORK Number 21 Bellamy On Mayor And Big Apple by Maryellen Gordon New York is number one, in both the od things and in screwing things up," narked Carol Bellamy, City Council esident Tuesday, in an appearance1 spon- ied by the Young Democrats. Approximately 8 5 people attended the entheld in Keating 1st, where Bellamy also ited that because of the financial im- jvements the City has undergone, she rates pKoch's politics a B-, 'Ed Koch can validly run on the financial nation," she confirmed, "however that lyincludes this primary, not the one three arsfrom now." Bellamy further added that energy and enthusiasm are Koch's other isilive points. On the negative side, she ited racial problems and education. "One n't'pander' to groups. It is unnecessary to len one's mouth all the time," she ex- lined. While Koch rates himself an 'A' for his ndling of the city's education system, llamy gives him a 'C, citing the high rate truancy and the high number of school ings. "We still have enormous problems re." 11975, the City was virtually bankrupt e to a number of factors, Bellamy stated. nmsCutsGo? lit was a larger problem than just New York ity; it is encountered by most older merican cities," she explained. She cited , by Mark Dillon \" ' ;• '<\Jr irious problems with the city's infrastruc- . Sweeping changes in,fe,derai student aid programs were The changes will affect.the amount of money available foi\ and the outflux of industries to signed into law August 13 by President Reagaitas part of a student aid and the ability of students to obtain fund&'fprv Mhern states that built-up to the '75 fiscal series of budget cms designed tp'help the nation1^ economy, higher education. -

Laszloandrew-2000-Everyframearembrandt.Pdf

EVERY FRAME A REMBRANDT ART AND PRACTICE OF CINEMATOGRAPHY Andrew Laszlo, A.S.C. with additional material by Andrew Quicke Focal Press An Imprint of Elsevier Boston Oxford Auckland Johannesburg Melbourne New Delhi Focal Press is an imprint of Elsevier Copyright © 2000 Butterworth-Heinemann (Si A member of the Reed Elsevier group All rights reserved. All trademarks found herein are property of their respective owners. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo copying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Permissions may be sought directly from Elsevier's Science and Technology Rights Department in Oxford, UK. Phone: (44) 1865 843830, Fax: (44) 1865 853333, e-mail: [email protected]. You may also complete your request on-line via the Elsevier homepage: http://www.elsevier.com by selecting "Customer Support" and then "Obtaining Permissions". 0 Recognizing the importance of preserving what has been written, Elsevier prints its books on acid-free paper whenever possible. GLOBAL E*sev*er suPPorts me efforts of American Forests and the Global ReLeaf REPEAT program in its campaign for the betterment of trees, forests, and our environment. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Laszlo, Andrew, 1926- Every frame a Rembrandt: art and practice of cinematography / Andrew Laszlo, with Andrew Quicke. p. cm. ISBN-13: 978-0-240-80399-9 ISBN-10: 0-240-80399-X (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Cinematography. I. Quicke, Andrew. II. Title. TR850.L38 2000 778.5—dc21 ISBN-13: 978-0-240-80399-9 99-058083 ISBN-10: 0-240-80399-X British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. -

Contents Your VOTE Speaks Volumes: Election Day Is Nov

Your VOTE speaks volumes: Election Day is Nov. 8th he day has finally come, mark- tee ballots must reach the county election law. I-177 prohibits the use of traps and Black. Precincts 61D, 62A, 62B, 62C, 62D, ing the end of what surely has office by the close of polls on Election Day at snares for animals by the public on any public 63A, and 63C can find their polling place at been an exhaustive season for 8pm, whether by mail or hand delivery. lands within Montana, with certain excep- Hope Lutheran Church, located at 2152 W. voters—and anyone else with It’s also not too late to register! Unlike tions. I-181 promotes research into developing Graf St. Precinct 63B votes in Shroyer Gym, eyes and ears. Ready or not, many states, late registration in Montana is therapies and cures for brain diseases and located in Bobcat Circle on the MSU Election Day will present itself available through Election Day at 8pm. This, injuries. I-182 expands access to medical Campus. Residents of precincts 67B, 67C, to Southwest Montana and all however, must be completed at the county marijuana. and 68C come together at Belgrade Special other United States citizens election office or the location designated by The pamphlet does not outline the Law Events Center, 220 Spooner Rd. Precincts whenT the polling places open at 7am on the County Election Administrator. Gallatin and Justice Facilities bond, which is a county- 68A and 68B are to vote at River Rock Tuesday, November 8th. Don’t let political County’s election office is located inside the level issue. -

Page 1 of 18 Moma | Press | Releases | 2000 | the Loss of Childhood

MoMA | press | Releases | 2000 | The Loss of Childhood Innocense Examined in Film Ex... Page 1 of 18 THE LOSS OF CHILDHOOD INNOCENSE EXAMINED IN FILM EXHIBITION For Immediate Release September 2000 The Lost Childhood October 5–December 14, 2000 The Roy and Niuta Titus Theaters 1 and 2 Childhood has been a favorite subject of filmmakers since the beginning of cinema. The Lost Childhood explores the period from 1955 to the present, when the nineteenth-century’s romanticized notion of the virginal, visionary child, so prevalent in films made before World War II, gave way to images of children hardened by war and harsh circumstances. This exhibition features approximately 50 feature films, shorts, experimental films, documentaries, and videos, from countries as far ranging as Brazil, Bulgaria, France, Hungary, India, Japan, and Mexico, and includes a diversity of genres, from horror to comedy, to the coming of age story and the fairy tale. The series is on view in The Roy and Niuta Titus Theaters 1 and 2 from October 5 through December 14, 2000. The Lost Childhood is a part of Open Ends, the final cycle of MoMA2000, and is organized by Joshua Siegel, Assistant Curator, Department of Film and Video. In the films and videos of The Lost Childhood, which takes its name from a short story by Graham Greene, adults are seen as either abusive and unloving, or immaturely self-absorbed, and therefore incapable of providing children with the comfort and protection they need. Home is seen as a place of violence and betrayal, not sanctuary, and so children are compelled to take flight in their dreams or take to the open road. -

Commencement 1981-1990

ttfit 4&T>» tfifi* JfOL THEJOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY (mm«t« T THE CLOSE. \CADEMIC YEAR ORDER OF PROCESSION Michael Beer ^'iluam H. Hugcins Ei-aine C. Davis Robert A. Lystad Bruce R. Eicher Peter B. Petersen Gareth M. Green Robert B. Pond, Sr. Robert E. Green Orest Ranum Richard L. Higgins Henry M. Seidel Roger A. Horn Ronald Walters THE GRADUATES MARSHALS William Harrington Dean W. Robinson THE DEANS MEMBERS OF THE SOCIETY OF SCHOLARS OFFICERS OF THE UNIVERSITY THE TRUSTEES Richard A. Macksey Owen M. Phillips THE FACULTIES CHIEF MARSHAL Thomas Fulton 1 111 (II MM UNS THE HONORARY DEGREE CANDIDATES THE PROVOST OF THE UNIVERSITY THE CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES HIE PRESIDENT OF THE UNIVERSITY ORDER OF EVENTS STEVEN MULLER President of the University, presiding Divertimenti No. 5 in C Major K. 187 W. A. Mozart PROCESSIONAL The audience is requested to stand as the Academic Procession moves into the area and to remain standing after the Invocation. Music for Royal Fireworks G. F. HANDEL Edition by Robert A. Boudreau Peabody Chamber Winds edward polochick, Conductor INVOCATION CLYDE R. SHALLENBERGER Director, Chaplaincy Service Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions THE NATIONAL ANTHEM GREETINGS ROBERT D. H. HARVEY Chairman of the Board of Trustees PRESENTATION OF NEW MEMBERS OF THE SOCIETY OF SCHOLARS Erwin H. Ackerkneciit Tiieodor Roller Henry T. Bahnson Thomas W. Langfitt Genevieve Comte-Bellot Sherman M. Mellinkoff Wilbur G. Downs Barixh Modan Leon Eisenberg John Van Sickle Clarence V. Hodges Pall F. Wehrle SCHOLARS PRESENTED BV RICHARD LONCAK.ER RONDO FROM DIVERTIMENTO IN E FLAT Gordon Jacob CONFERRING OF HONORARY DEGREES Marian Anderson Sir Isaiah Berlin Nathan W. -

Third Cinema in the United States, 1960-67

Copyright by Michael William O’Brien 2019 The Dissertation Committee for Michael William O’Brien Certifies that this is the approved version of the following Dissertation: Third Cinema in the United States, 1960-67 Committee: Mary Beltrán, Supervisor Mia Carter Shanti Kumar Thomas Schatz Janet Staiger Third Cinema in the United States, 1960-67 by Michael William O’Brien Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2019 Acknowledgements I would like to thank the following people, without whom this dissertation would not have been possible: Mary Beltrán, Mia Carter, Janet Staiger, Tom Schatz, Shanti Kumar, Matthew Bernstein, Michele Schreiber, Daniel Contreras, Steve Fogleman, Marten Carlson, Martin Sluk, Hampton Howerton, Paul Monticone, Colleen Montgomery, Collins Swords, Asher Ford, Marnie Ritchie, Ben Philipe, Mike Rennett, Daniel Krasnicki, Charmarie Burke, Mona Syed, Miko, my students, and my family. iv Abstract Third Cinema in the United States, 1960-1967 Michael William O’Brien, Ph.D. The University of Texas at Austin, 2019 Supervisor: Mary Beltrán This dissertation explores how cinema was an important outlet that artists and activists in the 1960s turned to in order to engage in cultural battles against various forms of institutional oppression. It links the aims and struggles of Americans making socially conscious films about racial discrimination to a broader category of image warfare known as Third Cinema. Third Cinema is generally applied to the notable proliferation of politically engaged films and revolutionary filmmaking theories developed in economically depressed and/or colonially exploited countries. -

Canon Cover Story EXT. 20000

Jon Fauer, ASC www.fdtimes.com Dec 2011 Issue 45 The Journal of Art, Technique and Technology in Motion Picture Production Worldwide Canon Cover Story EXT. 20,000 ISO - NIGHT Canon’s Cinema EOS System and C300 35mm Cameras FDTimes First Look New ZEISS Anamorphic Lenses, Compact Zoom, CP.2 Primes Exclusive Interviews Angenieux, Leica, Canon IBC and Year-End Gear Wrap Up April 2010 1 Inside FDTimes Art, Technique and Technology Dec 2011, Issue 45 Film and Digital Times is written, edited, and published by Jon Painting with Light: EXTERIOR - NIGHT ......................................................... 3 Fauer, ASC, an award-winning Cinematographer, Director, and Canon C300 Report .................................................................................4-7 author of 14 bestselling books. With inside-the-industry information, Canon C300 Lenses and Specs ................................................................... 8 Film and Digital Times is delivered to you by subscription or invita- Practical Productions with Canon C300 ........................................................ 9 tion, online or on paper. To subscribe: www.fdtimes.com/subscribe C300 CMOS Image Sensor Details ............................................................. 10 © 2011 Film and Digital Times, Inc. Cinema EOS Premieres in Hollywood .....................................................11-12 Cinema EOS Premieres in NY ..................................................................... 13 Canon’s Managing Director Masaya Maeda ...........................................14-15 -

AUSTRALIAN OFFICIAL JOURNAL of TRADE MARKS 12 October 2006

Vol: 20 , No. 39 12 October 2006 AUSTRALIAN OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF TRADE MARKS Did you know a searchable version of this journal is now available online? It's FREE and EASY to SEARCH. Find it at http://pericles.ipaustralia.gov.au/ols/epublish/content/olsEpublications.jsp or using the "Online Journals" link on the IP Australia home page. The Australian Official Journal of Designs is part of the Official Journal issued by the Commissioner of Patents for the purposes of the Patents Act 1990, the Trade Marks Act 1995 and Designs Act 2003. This Page Left Intentionally Blank (ISSN 0819-1808) AUSTRALIAN OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF TRADE MARKS 12 October 2006 Contents General Information & Notices IR means "International Registration" Amendments and Changes Application/IRs Amended and Changes ...................... 11417 Registrations/Protected IRs Amended and Changed ................ 11418 Applications for Extension of Time ...................... 11417 Applications/IRs Accepted for Registartion/Protection .......... 11138 Applications/IRs Filed Nos 1136262 to 1137336 ............................. 11123 Applications/IRs Lapsed, Withdrawn and Refused Lapsed ...................................... 11419 Withdrawn..................................... 11419 Refused ...................................... 11419 Assignments, Trasnmittals and Transfers .................. 11419 Cancellations of Entries in Register ...................... 11421 Corrigenda ...................................... 11422 Notices ........................................ 11416 Opposition -

Santiago De Compostela Novembro 2014

Santiago de Compostela novembro 2014 Santiago de Compostela de Compostela Santiago PREZO ENTRADAS PROXECCIÓNS GRATUÍTAS 4 euros • Entrega dos Premios Cineuropa • Sección Oficial * • Docs Cineuropa • Panorama Internacional • Docs Music • Fantastique Compostela • Cando Tiburón devorou o cine: • Restrospectiva Nils Malmros * ascenso e caída do Novo Hollywood * excepto filmes gratuítos para os que cómpre retirar entrada: • Cincuentenario Cole Porter -U na nouvelle amie (proxección inaugural, • Berlín: 25 anos sen muro T. Principal, 9 novembro) • Ao outro lado do muro: o cine na RDA -M agical Girl (proxección de entrega do Premio Cineuropa: • Tributo: o último Resnais Bárbara Lennie, T. Principal, 16 novembro) • Foco Bertrand Bonello - Ida (proxección Premio Lux, T. Principal, 18 novembro) • Cinefilias -T he Casanova Variations (proxección de entrega do • Panorama Audiovisual Galego Premio Cineuropa: Paulo Branco, T. Principal, 22 novembro) • Disidencias - Sorg og glæde (Sorrow and Joy) (proxección de entrega do Teatro Principal e Salón Teatro Premio Cineuropa: Nils Malmros, Salón Teatro, 25 novembro) cómpre retirar a entrada previamente Bono 10 películas + catálogo: 30 euros no Teatro Principal (15.30-22.00 h) Catálogo: 2 euros CGAC (Centro Galego de Arte Comtemporánea) Maratón Cineuropa (T. Principal, 28 novembro): 6 euros e Centro Cultural Afundación (Rúa do Vilar, 19) venda anticipada entrada libre ata completar a capacidade entradas.abanca.com / 902 434 443 Teatro Principal (15.30-22.00 h) venda inmediata Teatro Principal (ata 5 minutos