“For the Education and Elevation of the Youth”: the Juvenile Instructor and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PHILIP L. BARLOW [email protected]

PHILIP L. BARLOW [email protected] EDUCATION Th.D. (1988) Harvard Divinity School, American Religious History & Culture M.T.S. (1980) Harvard, History of Christianity B.A. (1975) Weber State College, magna cum laude, History PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE 2017: Inaugural Neal A. Maxwell Fellow, Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, Brigham Young University (calendar year) 2007—present: inaugural Leonard J. Arrington Professor of Mormon History & Culture, Dept. of History, Religious Studies Program, Utah State University 2011–2014: Director, Program in Religious Studies, Dept. of History, Utah State University 2001—2007: Professor of Christian History, Hanover College, Dept. of Theological Studies; (Associate Professor: 1994-2000; Dept. Chair: 1997-99; Assistant Professor: 1990-1994) 2006—2007: Associate Research Fellow, The Center for the Study of Religion & American Culture (at Indiana University/Purdue University at Indianapolis) 1988—90: Mellon Post-doctoral Fellow, University of Rochester, Dept. of Religion & Classics 1979–1985: Instructor, LDS Institute of Religion, Cambridge, MA SELECTED SERVICE/ACTIVITIES/HONORS (see also honors under: PUBLICATIONS/BOOKS) Periodic interviews in print and on camera in various media, including Associated Press, NBC News, CNN, CNN Online, CBS News, PBS/Frontline, National Public Radio, Utah Public Radio, the Boston Globe, New York Times, Chicago Tribune, USA Today, USA Today/College, Washington Post, Salt Lake Tribune, Deseret News, Mormon Times, and others, and news outlets and journals internationally in England, Germany, Israel, Portugal, France, and Al Jazeera/English. Board of Advisors, Executive Committee, Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, Brigham Young University (2017–present). Co-Director, Summer Seminar on Mormon Culture: ““Mormonism Engages the World: How the LDS Church Has Responded to Developments in Science, Culture, and Religion.” Brigham Young University, June–August 2017. -

The Secret Mormon Meetings of 1922

University of Nevada, Reno THE SECRET MORMON MEETINGS OF 1922 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History By Shannon Caldwell Montez C. Elizabeth Raymond, Ph.D. / Thesis Advisor December 2019 Copyright by Shannon Caldwell Montez 2019 All Rights Reserved UNIVERSITY OF NEVADA RENO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by SHANNON CALDWELL MONTEZ entitled The Secret Mormon Meetings of 1922 be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS C. Elizabeth Raymond, Ph.D., Advisor Cameron B. Strang, Ph.D., Committee Member Greta E. de Jong, Ph.D., Committee Member Erin E. Stiles, Ph.D., Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School December 2019 i Abstract B. H. Roberts presented information to the leadership of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in January of 1922 that fundamentally challenged the entire premise of their religious beliefs. New research shows that in addition to church leadership, this information was also presented during the neXt few months to a select group of highly educated Mormon men and women outside of church hierarchy. This group represented many aspects of Mormon belief, different areas of eXpertise, and varying approaches to dealing with challenging information. Their stories create a beautiful tapestry of Mormon life in the transition years from polygamy, frontier life, and resistance to statehood, assimilation, and respectability. A study of the people involved illuminates an important, overlooked, underappreciated, and eXciting period of Mormon history. -

Juvenile Instructor 16 (1 April 1881): 82

G. G.001 G. “Old Bottles and Elephants.” Juvenile Instructor 16 (1 April 1881): 82. Discusses earthenware manufacture in antiquity. Points out that some bottles and pottery vessels dug up on the American continent resemble elephants. Also mentions that the discovery of elephant bones in the United States tend to prove the truth of the Jaredite record. [A.C.W.] G.002 G., L. A. “Prehistoric People.” SH 51 (16 November 1904): 106-7. Quoting a clipping from the Denver Post written by Doctor Baum who had conducted expeditions in the southwestern United States, the author wonders why the archaeologists do not read the Book of Mormon to nd answers to their questions about ancient inhabitants of America. [J.W.M.] G.003 Gabbott, Mabel Jones. “Abinadi.” Children’s Friend 61 (September 1962): 44-45. A children’s story of Abinadi preaching to King Noah. [M.D.P.] G.004 Gabbott, Mabel Jones. “Alma.” Children’s Friend 61 (October 1962): 12-13. A children’s story of how Alma believed Abinadi and then organized the Church of Christ after preaching in secret to the people. [M.D.P.] G.005 Gabbott, Mabel Jones. “Alma, the Younger.” Children’s Friend 61 (December 1962): 18-19. A children’s story of the angel that appeared to Alma the Younger and the four sons of Mosiah and how they were converted by this experience. [M.D.P.] G.006 Gabbott, Mabel Jones. “Ammon.” Children’s Friend 62 (February 1963): 18-19. A children’s story of Ammon teaching among the Lamanites. [M.D.P.] G.007 Gabbott, Mabel Jones. -

Juvenile Instructor

<&' =«^5rf^^ »t,'I.M ,'» t«.M».M »»ti'n»»l,M|«H.» (•IH^*M l i'ktM.«SiM.MI.<l«lM*>lk*M«Mk«M.#%MU , l>MUM*M||>|,Mt«i|^-a^L ^t3^^.^=5^"'* l t M lfc 1 r=;: j9^^: I THE ^O gu AN ILLUSTRATED PAPER, (Published Semi-Monthly.) 3? HOLIITSSS TO THE LOE-D m m> ? O "p)^ =^' !"' i ^'^ a^ "*# getting get understanding.—SOLOJ/ION. Cl^ There is no Excellence without Labor. EXj^EIR. QEOEGE Q. C -A. 3ST £T O N" , E:DITO^. Volume Twelve, For the Year 1877. PUBLISHED BY GEORGE Q. CANNON, SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH TERRITORY. , , , l il „'t.*t t (M,»ti«M,»t|,M,*<» »lH'«.»0 t «.»M'lA<'(.H >«M«WlM*lt»m»l|»-tf^ff*-»"3^g^3C ^*) J^^n^ hl'» <>l.'»tl'l.rlU liMtl><.(l| l l lHiMt *l*,^*- ~ : %*£;* y til Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from Corporation of the Presiding Bishop, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints http://www.archive.org/details/juvenileinstruct121geor 1 1 COiLTTIElIfcTTiS. Alfred the Great 1 False Religion 70 Antipodes, A Trip to Our 10, 22, 33, 46, 59 Fortress of Ham 90 Arizona, Ancient Ruins in 21 Freak of a Dog, Curious 156 Animal Trades and Callings 40 Fred.- Danielson's Lesson 165 Australia 130 Familiar Plants 225, 245, 281 Act from Principle 191 Flying Squirrels 247 Anomalies of English Spelling 242 Ambition 250 "Great Harry," The 25 Architecture in Salt Lake City 259 Great Cemetery, A 126 Great Calamity, A 166 Biography, Joseph Smith, the Prophet 9. -

True Greatness

CHAPTER 11 True Greatness “Giving consistent effort in the little things in daytoday life leads to true greatness.” From the Life of Howard W. Hunter President Howard W. Hunter taught that true greatness comes not from worldly success but from “thousands of little deeds . of service and sacrifice that constitute the giving, or losing, of one’s life for others and for the Lord.” 1 President Hunter lived his life ac- cording to this teaching. Rather than seeking the spotlight or the acclaim of others, he performed daily deeds of service and sacrifice that were often unnoticed. One example of President Hunter’s relatively unnoticed service was the care he gave to his wife as she struggled with declining health for more than a decade. In the early 1970s, Claire Hunter began experiencing headaches and memory loss. She later suffered several small strokes, which made it difficult for her to talk or use her hands. When she began to need constant care, President Hunter provided as much as he could while also fulfilling his responsibili- ties as an Apostle. He arranged for someone to stay with Claire during the day, but he cared for her at night. A cerebral hemorrhage in 1981 left Claire unable to walk or speak. Nevertheless, President Hunter sometimes helped her out of her wheelchair and held her tightly so they could dance as they had done years earlier. After Claire experienced a second cerebral hemorrhage, doctors insisted that she be placed in a care center, and she remained there for the last 18 months of her life. -

“The Osborn Files” the History of the Family of Charlotte Osborn Potter, Her Children, and Her Ancestry

“The Osborn Files” The History of the family of Charlotte Osborn Potter, Her children, and her ancestry Written and complied by Steven G. Mecham Text only is given below THE CHARLOTTE OSBORN POTTER FAMILY The children of Charlotte Osborn Potter at the time of her death remembered their mother as a kind and indulgent mother and the instrument in the hands of God of their conversion to the Gospel of Christ (1). Her story and the lives are her children are intertwined and hence this record contains an accounting of their lives. Charlotte Osborn, was born April 14, 1795 in Pawlet, Rutland County, Vermont, the eldest daughter of Justus Osborn and Susannah Dickerman(2). She was found living with her family in Pawlet, Vermont in 1800 (3), but the family moved to Pomfret Township, Niagara County, New York between 1809 or 1810 (4). She moved with her family from Chautauqua County, New York westward to Erie County, Pennsylvania, settling in Fairview Township some time between 1815 and 1816. She along with her father attended the first Methodist class held in his log cabin in Erie County, Pennsylvania in 1817(5). She met and married David Potter Jr. in Erie County, Pennsylvania in 1817 (6). They settled in then, Troy Township, Cuyahoga County, Ohio, which later became Avon Township, Erie County, Pennsylvania (7). In 1820, the area was still more or less frontier, so settlements and counties were in flux Their first child, Benjamin Potter was born in 1818 (8), a daughter, Esther Potter, was born in 1819 (9). Neither child lived to adulthood. -

Selective Bibliography on African-Americans and Mormons 1830-1990

Selective Bibliography on African-Americans and Mormons 1830-1990 Compiled by Chester Lee Hawkins INTRODUCTION AFRICAN-AMERICAN MORMONS until recently have received little atten- tion, at least partly because of the limited bibliographical listings that coordinate the sources available for historical or scholarly research papers on their history. This bibliography, though selective, attempts to change that, to meet the needs of the LDS scholarly and religious community. This work catalogues a variety of reference materials on the role of African-Americans in Mormon history from 1830 to 1990. Included are books and monographs, general and LDS serials, newspaper arti- cles, theses and dissertations, pamphlets, and unpublished works such as journal entries, letters, and speeches, as well as materials relating to the 1978 revelation that "all worthy males" can be ordained to the priesthood in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. I have divided the bibliography into nine major divisions and have included many annotated entries. It is my hope that this work will assist others who are interested in undertaking research projects that will lead to a more definitive and scholarly study of African-Americans' contributions to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. This Selective Bibliography is important for all who wish to contribute to the study of African-Americans in the Mormon church. It is my hope that Latter-day Saints today will understand and appreciate the joys and struggles that African-Americans have had throughout the history of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. CHESTER LEE HAWKINS is the government document clerk for the U.S. -

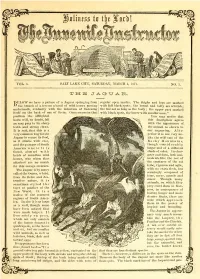

Juvenile Instructor

VOL. 6. SALT LAKE CITY, SATURDAY, MARCH i, 1871. NO. 5. THIE J J± Or TJ J± tt. BELOW we have a picture of a Jaguar springing from regular open marks. The thighs and legs are marked full the brancli of a tree on a band of wild horses passing with black spots ; the breast and belly are whitish ; evidently with the intention of fastening the tail not so long as the underneath, body ; the upper part marked itself on the back of one of them. Once secure in that with black spots, the lower with smaller ones." position the affrighted You may notice that horse will, no doubt, fall this description agrees an easy prey to its sharp with the appearance of. teeth and strong claws. the animal as shown in Tt is said, that this is a our engraving. Alto- very common way for the gether it is not very un- Jaguar to secure its food, like the wild cats of the as it climbs with ease, Rocky Mountains, and the pampas of South though cons i d e r a b 1 y America where it is larger and of a different found, abou n d with shade of color. In char- herds of countless wild acter and form, both ani- horses, who when thus mals are like the rest of attacked are no match the creatures of the cat vigorous for this savage creature. tribe, and agile, with no extra flesh, but The Jaguar is by many seemingly composed of called the Ounce, whilst, bone, nerve, muscle and from its fierce and des- sinew. -

Juvenile Instructor

FROM THE UBRARY OF THE OESERET SUNDAY SCHOOL UNION BOARD 50 NORTH MAIN STREET J ^Qc^^^- &w^mKE-GfTY I. UTAH^^^^g^R^ ^' 25 *. Wt O^ T ^o M JUVENILE INSTRUCTOR 13? IliTtlf *<* mi i R'; It 31 ( Published Every Alternate Saturday.) siitlttt ilfitilt til fi m HOLINESS TO THE LORD, -$; -«-£iS^St^3-^J-- Jfut iui£7i aJZ tft.t/ getting get understanding. — SOLOJVLOJT. Ihere is no Excellence without Labor. :e i_, :d e: es. g-eo^gs-e: q. c _^_ nsr 2^" o ar, editoe. Volume Nine, For the Year 1874. (PZTgLISHEQ £Y G-EOIi&E O. CjlJTJTOJT, SALT LAKE QWY,, VTAB TERRITORY. '"• ,^(5—-^^^SJtoM^MU'liMMMiMU'liI ti» .»» UMli'l, "".rg^s^Q THE LIBRARY OF THE DESERET SUNDAY SCHOOL UNION BOARD 50 NORTH MAIN STREET SALT LAKE CITX I. UTAH ±^,C: .t^. - Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from Corporation of the Presiding Bishop, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints http://www.archive.org/details/juvenileinstruct91geor 1 COIJ"TEE"TS. Annie and Willie's Prayer, 8 Diet of Leather Iron, Etc., A 5 Anecdotes of Painters, 9, 16, 29, 46, 52, 65, 82, 92, 104, Dying Words, 87 118,128, 137, 146,167, 171 Depend on Yourself, 89 Alphabet of Proverbs, 27 Diana of the Ephesians, 157 Amy's Pets, 39 Drowned, How to Save the 177 Ancient Mill, An 45 Date Palm, The 211 All Hail the Jubilee, 84 Deaf and Dumb Pygmies, The 221 Argus, 181 Drinking Vinegar, 228 Aeasdz, the Boy 208, 227, 230 Dollar Mark, 288 Adventures of a Rag, 212 Aqueous Agencies, 218 Eastern Omnibus, 1 Amsterdam, 225 Editorial Thoughts, 6, 18, 30, 42, 54, 66. -

Minding Business: a Note on “The Mormon Creed”

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 26 Issue 4 Article 8 10-1-1986 Minding Business: A Note on “The Mormon Creed” Michael Hicks Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Recommended Citation Hicks, Michael (1986) "Minding Business: A Note on “The Mormon Creed”," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 26 : Iss. 4 , Article 8. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol26/iss4/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Hicks: Minding Business: A Note on “The Mormon Creed” minding business A note on the mormon creed michael hicks on christmas day 1844 william wines phelps wrote a letter to william smith in which he described mormonism as the great leveling machine of creeds 1 smith would have understood phelps s meaning his late brother the prophetjosephprophetjoseph had always maintained that mormonism should not only resist the pat confessions of christian orthodoxy which as he said set up stakes to the almighty 2 but also resist pat formulations of mormon belief itself the latter day saints have no creed joseph had once said but are ready to believe all true principles that exist as they are made manifest from time to time byet3yet3 setyet in september 1844 three months before phelps wrote his christmas letter william smith scolded a new sakkakyakmorkyork congregation -

Looking Beyond the Borders of Mexico: Historian Andrew Jenson and the Opening of Mormon Missionary Work in Latin America

Bray and Neilson: Looking Beyond the Borders of Mexico 1 Looking Beyond the Borders of Mexico: Historian Andrew Jenson and the Opening of Mormon Missionary Work in Latin America Justin R. Bray and Reid L. Neilson On July 11, 1923, Assistant Church Historian Andrew Jenson met at the office of the First Presidency in Salt Lake City, Utah, to report on his four- month, twenty-three-thousand-mile expedition throughout Central and South America from January to May of that year. Jenson, the foremost representa- tive of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints to visit the countries south of the Mexican border since Elder Parley P. Pratt in 1851, had eager- ly waited for two months to give to Presidents Heber J. Grant, Charles W. Penrose, and Anthony W. Ivins his glowing assessment of Latin America as a potential missionary field.1 The journey through Latin America significantly differed from Jenson’s earlier overseas expeditions. Later described as “the most traveled man in JUSTIN R. BR A Y ([email protected]) is an oral historian for the LDS Church History Department in Salt Lake City, Utah. He received a BA in history and Latin American Studies from Brigham Young University in 2011 and is currently pursuing an MA in history at the University of Utah. REI D L. NEILSON ([email protected]) is managing director of the Church History Department. He received his BA in international relations from Brigham Young University in 1996. He also took graduate degrees in American history and business administration at BYU in 2001 and 2002, respectively. -

Faith and Intellect As Partners in Mormon History

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU Arrington Annual Lecture Leonard J. Arrington Mormon History Lectures 11-7-1995 Faith and Intellect as Partners in Mormon History Utah State University Press Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/arrington_lecture Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Utah State University Press, "Faith and Intellect as Partners in Mormon History" (1995). Arrington Annual Lecture. Paper 1. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/arrington_lecture/1 This Lecture is brought to you for free and open access by the Leonard J. Arrington Mormon History Lectures at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arrington Annual Lecture by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LEONARD J. ARRINGTON MORMON HISTORY LECTURE SERIES No.1 FAITH AND INTELLECT AS PARTNERS IN MORMON HISTORY by Leonard J. Arrington November 7,1995 Sponsored by Special Collections & Archives Merrill Library Utah State University Logan, Utah Introduction Throughout its history the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, through its leaders and apologists, has declared that faith and intellect have a mutually supportive relationship.1 Faith opens the way to knowledge, and knowledge, in turn, often reaches up to reverence. Spiritual understanding comes with faith and is supported by intellect. Church President Spencer W. Kimball told Brigham Young University students in his “Second Century Address” in 1976: “As LDS scholars you must speak with authority and excellence to your professional colleagues in the language of scholarship, and you must also be literate in the language of spiritual things.”2 The theme of faith and intellect, not faith versus intellect, was established in the early days of the Restoration.