Control of Fluxes in Metabolic Networks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leeds Thesis Template

Determining the Link Between Genome Integrity and Seed Quality Robbie Michael Gillett Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds Faculty of Biological Sciences School of Biology January, 2017 - ii - The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. The right of Robbie M. Gillett to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. © 2016 The University of Leeds and Robbie Michael Gillett - iii - Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor Dr Christopher West and co-supervisor Dr. Wanda Waterworth for all of their support, expertise and incredible patience and for always being available to help. I would like to thank Aaron Barrett, James Cooper, Valérie Tennant, and all my other friends at university for their help throughout my PhD. Thanks to Vince Agboh and Grace Hoysteed for their combined disjointedness and to Ashley Hines, Daniel Johnston and Darryl Ransom for being a source of entertainment for many years. I would like to thank my international Sona friends, Lindsay Hoffman and Jan Maarten ten Katen. Finally unreserved thanks to my loving parents who supported me throughout the tough times and to my Grandma and Granddad, Jean and Dennis McCarthy, who were always very vocal with their love, support and pride. -

The Microbiota-Produced N-Formyl Peptide Fmlf Promotes Obesity-Induced Glucose

Page 1 of 230 Diabetes Title: The microbiota-produced N-formyl peptide fMLF promotes obesity-induced glucose intolerance Joshua Wollam1, Matthew Riopel1, Yong-Jiang Xu1,2, Andrew M. F. Johnson1, Jachelle M. Ofrecio1, Wei Ying1, Dalila El Ouarrat1, Luisa S. Chan3, Andrew W. Han3, Nadir A. Mahmood3, Caitlin N. Ryan3, Yun Sok Lee1, Jeramie D. Watrous1,2, Mahendra D. Chordia4, Dongfeng Pan4, Mohit Jain1,2, Jerrold M. Olefsky1 * Affiliations: 1 Division of Endocrinology & Metabolism, Department of Medicine, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, California, USA. 2 Department of Pharmacology, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, California, USA. 3 Second Genome, Inc., South San Francisco, California, USA. 4 Department of Radiology and Medical Imaging, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA. * Correspondence to: 858-534-2230, [email protected] Word Count: 4749 Figures: 6 Supplemental Figures: 11 Supplemental Tables: 5 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online April 22, 2019 Diabetes Page 2 of 230 ABSTRACT The composition of the gastrointestinal (GI) microbiota and associated metabolites changes dramatically with diet and the development of obesity. Although many correlations have been described, specific mechanistic links between these changes and glucose homeostasis remain to be defined. Here we show that blood and intestinal levels of the microbiota-produced N-formyl peptide, formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (fMLF), are elevated in high fat diet (HFD)- induced obese mice. Genetic or pharmacological inhibition of the N-formyl peptide receptor Fpr1 leads to increased insulin levels and improved glucose tolerance, dependent upon glucagon- like peptide-1 (GLP-1). Obese Fpr1-knockout (Fpr1-KO) mice also display an altered microbiome, exemplifying the dynamic relationship between host metabolism and microbiota. -

Style Specifications Thesis

Structural Studies of Salvage Enzymes in Nucleotide Biosynthesis Martin Welin Faculty of Natural Resources and Agricultural Sciences Department of Molecular Biology Uppsala Doctoral thesis Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Uppsala 2007 Acta Universitatis Agriculturae Sueciae 2007:21 ISSN 1652-6880 ISBN 978-91-576-7320-6 © 2007 Martin Welin, Uppsala Tryck: SLU Service/Repro, Uppsala 2007 Abstract Welin, M., 2007. Structural Studies of Salvage Enzymes in Nucleotide Biosynthesis. Doctoral dissertation. ISSN 1652-6880, ISBN 978-91-576-7320-6 There are two routes to produce deoxyribonucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs) precursors for DNA synthesis, the de novo and the salvage pathways. Deoxyribonucleoside kinases (dNKs) perform the initial phosphorylation of deoxyribonucleosides (dNs). Furthermore, they can act as activators for several medically important nucleoside analogs (NAs) for treatment against cancer or viral infections. Several disorders are characterized by mutations in enzymes involved in the nucleotide biosynthesis, such as Lesch-Nyhan disease that is linked to hypoxanthine guanine phosphoribosyltransferase (HPRT). In this thesis, the structures of human thymidine kinase 1 (TK1), a mycoplasmic deoxyadenosine kinase (Mm-dAK), and phosphoribosyltransferase domain containing 1 (PRTFDC1) are presented. Furthermore, a structural investigation of Drosophila melanogaster dNK (Dm-dNK) N64D mutant was carried out. The obtained structural information reveals the basis for substrate specificity for TKs and the bacterial dAKs. The TK1 revealed a structure different from other known dNK structures, containing an α/β domain similar to the RecA-F1ATPase family, and a lasso-like domain stabilized by a structural zinc. The Mm-dAK structure was similar to its human counterparts, but with some alterations in the proximity of the active site. -

Biochemical Basis for Differential Deoxyadenosine Toxicity To

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 76, No. 5, pp. 2434-2437, May 1979 Medical Sciences Biochemical basis for differential deoxyadenosine toxicity to T and B lymphoblasts: Role for 5'-nucleotidase (deoxyadenosine kinase/deoxyadenylate kinase/immunodeficiency) ROBERT L. WORTMANN, BEVERLY S. MITCHELL, N. LAWRENCE EDWARDS, AND IRVING H. Fox Human Purine Research Center, Departments of Internal Medicine and Biological Chemistry, Clinical Research Center, University of Michigan Medical Center, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109 Communicated by James B. Wyngaarden, March 7, 1979 ABSTRACT Deoxyadenosine metabolism was investigated tained from Calbiochem. Erythro-9-[3-(2-hydroxynonyl)]- in cultured human cells to elucidate the biochemical basis for adenine (EHNA) was a gift from G. B. Elion of Burroughs the sensitivity of T lymphoblasts and the resistance of B lym- Wellcome (Research Triangle Park, NC). Horse serum was phoblasts to deoxyadenosine toxicity. T lymphoblasts have a 20- to 45-fold greater capacity to synthesize deoxyadenosine nu- obtained from Flow Laboratories (Rockville, MD), and Eagle's cleotides than B lymphoblasts at deoxyadenosine concentrations minimal essential medium was purchased from GIBCO. From of 50-300 ,uM. During the synthesis of dATP, T lymphoblasts Amersham/Searle, [U-14C]deoxyadenosine (505 mCi/mmol), accumulate large quantities of dADP, whereas B lymphoblasts [8-14C]hypoxanthine (52.5 mCi/mmol), and [U-14C]deoxy- do not accumu ate dADP. Enzymes affecting deoxyadenosine adenosine monophosphate (574 mCi/mmol) were purchased; nucleotide synthesis were assayed in these cells. No substantial and, from ICN, [8-14C]adenosine monophosphate (34.4 mCi/ differences were evident in activities of deoxyadenosine kinase (ATP: deoxyadenosine 5'-phosphotransferase, EC 2.7.1.76) or mmol) was purchased (1 Ci = 3.7 X 1010 becquerels). -

The Metabolic Building Blocks of a Minimal Cell Supplementary

The metabolic building blocks of a minimal cell Mariana Reyes-Prieto, Rosario Gil, Mercè Llabrés, Pere Palmer and Andrés Moya Supplementary material. Table S1. List of enzymes and reactions modified from Gabaldon et. al. (2007). n.i.: non identified. E.C. Name Reaction Gil et. al. 2004 Glass et. al. 2006 number 2.7.1.69 phosphotransferase system glc + pep → g6p + pyr PTS MG041, 069, 429 5.3.1.9 glucose-6-phosphate isomerase g6p ↔ f6p PGI MG111 2.7.1.11 6-phosphofructokinase f6p + atp → fbp + adp PFK MG215 4.1.2.13 fructose-1,6-bisphosphate aldolase fbp ↔ gdp + dhp FBA MG023 5.3.1.1 triose-phosphate isomerase gdp ↔ dhp TPI MG431 glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate gdp + nad + p ↔ bpg + 1.2.1.12 GAP MG301 dehydrogenase nadh 2.7.2.3 phosphoglycerate kinase bpg + adp ↔ 3pg + atp PGK MG300 5.4.2.1 phosphoglycerate mutase 3pg ↔ 2pg GPM MG430 4.2.1.11 enolase 2pg ↔ pep ENO MG407 2.7.1.40 pyruvate kinase pep + adp → pyr + atp PYK MG216 1.1.1.27 lactate dehydrogenase pyr + nadh ↔ lac + nad LDH MG460 1.1.1.94 sn-glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase dhp + nadh → g3p + nad GPS n.i. 2.3.1.15 sn-glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase g3p + pal → mag PLSb n.i. 2.3.1.51 1-acyl-sn-glycerol-3-phosphate mag + pal → dag PLSc MG212 acyltransferase 2.7.7.41 phosphatidate cytidyltransferase dag + ctp → cdp-dag + pp CDS MG437 cdp-dag + ser → pser + 2.7.8.8 phosphatidylserine synthase PSS n.i. cmp 4.1.1.65 phosphatidylserine decarboxylase pser → peta PSD n.i. -

Q 297 Suppl USE

The following supplement accompanies the article Atlantic salmon raised with diets low in long-chain polyunsaturated n-3 fatty acids in freshwater have a Mycoplasma dominated gut microbiota at sea Yang Jin, Inga Leena Angell, Simen Rød Sandve, Lars Gustav Snipen, Yngvar Olsen, Knut Rudi* *Corresponding author: [email protected] Aquaculture Environment Interactions 11: 31–39 (2019) Table S1. Composition of high- and low LC-PUFA diets. Stage Fresh water Sea water Feed type High LC-PUFA Low LC-PUFA Fish oil Initial fish weight (g) 0.2 0.4 1 5 15 30 50 0.2 0.4 1 5 15 30 50 80 200 Feed size (mm) 0.6 0.9 1.3 1.7 2.2 2.8 3.5 0.6 0.9 1.3 1.7 2.2 2.8 3.5 3.5 4.9 North Atlantic fishmeal (%) 41 40 40 40 40 30 30 41 40 40 40 40 30 30 35 25 Plant meals (%) 46 45 45 42 40 49 48 46 45 45 42 40 49 48 39 46 Additives (%) 3.3 3.2 3.2 3.5 3.3 3.4 3.9 3.3 3.2 3.2 3.5 3.3 3.4 3.9 2.6 3.3 North Atlantic fish oil (%) 9.9 12 12 15 16 17 18 0 0 0 0 0 1.2 1.2 23 26 Linseed oil (%) 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 6.8 8.1 8.1 9.7 11 10 11 0 0 Palm oil (%) 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 3.2 3.8 3.8 5.4 5.9 5.8 5.9 0 0 Protein (%) 56 55 55 51 49 47 47 56 55 55 51 49 47 47 44 41 Fat (%) 16 18 18 21 22 22 22 16 18 18 21 22 22 22 28 31 EPA+DHA (% diet) 2.2 2.4 2.4 2.9 3.1 3.1 3.1 0.7 0.7 0.7 0.7 0.7 0.7 0.7 4 4.2 Table S2. -

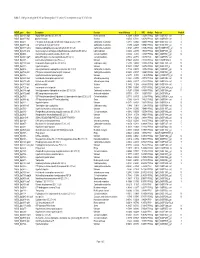

Table 7. GAS Genes Upregulated (+Z) and Downregulated (-Z) on Day 32 in Comparison to Day 16 of Infection

Table 7. GAS genes upregulated (+Z) and downregulated (-Z) on day 32 in comparison to day 16 of infection. M5005_gene Gene Description Function mean difference Z NFD Analysis Probe-set Probe # M5005_Spy1808 argS Arginyl-tRNA synthetase (EC 6.1.1.19) Protein synthesis -1.72298 -4.95958 0.14279 PPA1&2 SpM1_ChORF2151_s_at 8 M5005_Spy0317 hlyX putative hemolysin Virulence -2.02534 -4.71231 0.30786 PPA1&2 SpM1_ChORF0378_s_at 5 M5005_Spy0475 - PTS system, beta-glucoside-specific IIABC component (EC 2.7.1.69) Carbohydrate metabolism -1.47813 -4.48425 0.62109 PPA1&2 SpM1_ChORF0572_s_at 4 M5005_Spy0577 atpF ATP synthase B chain (EC 3.6.3.14) Carbohydrate metabolism -1.7496 -4.45203 0.68541 PPA1&2 SpM1_ChORF0756_s_at 11 M5005_Spy1637 lacB.2 Galactose-6-phosphate isomerase lacB subunit (EC 5.3.1.26) Carbohydrate metabolism -1.94768 -4.37397 0.86962 PPA1&2 SpM18_ChORF1990_s_at 15 M5005_Spy1485 accA Acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase carboxyl transferase subunit beta (EC 6.4.1.2) Lipid metabolism -1.67854 -4.23953 1.30699 PPA1&2 SpM1_ChORF1743_s_at 4 M5005_Spy0500 - N-acetylmuramoyl-L-alanine amidase (EC 3.5.1.28) Cell wall metabolism -1.54852 -4.2346 1.32657 PPA1&2 SpM1_ChORF0601_s_at 12 M5005_Spy0608 rgpFc alpha-L-Rha alpha-1,3-L-rhamnosyltransferase (EC 2.4.1.-) Cell wall metabolism -0.77914 -4.07772 0.58709 PPA3 SpM1_ChORF0792_s_at M5005_Spy1697 - 4-amino-4-deoxychorismate lyase (EC 4.-.-.-) Unknown -1.55045 -4.04336 2.35339 PPA1&2 SpM18_ChORF2056_at 12 M5005_Spy1108 metK S-adenosylmethionine synthetase (EC 2.5.1.6) Cellular processing -1.57308 -3.94036 -

Table S1A. Enterococcus Faecium Phage 9181 Genome Organization and Features

Table S1A. Enterococcus faecium phage 9181 genome organization and features Phage 9181 genome annotation Feature Gene Gene Length Strand blastp Best-Hit cut-off Best-Hit % % % E-value Predicted Function ID Start Stop (0.001) Number Accession Gaps Identities Positives ORF1 15 959 945 + N-acetylmuramoyl-L- OJG47739 6 53 66 7.88E-98 N-acetylmuramoyl-L- alanine amidase alanine amidase Enterococcus hirae ORF2 1362 1601 240 + hypothetical protein ORF3 1605 1853 249 + hypothetical protein ORF4 1866 2048 183 + hypothetical protein ORF5 2045 2185 141 + hypothetical protein ORF6 2199 2483 285 + hypothetical protein ORF7 2496 2906 411 + hypothetical protein APU00246 0 45 68 2.70E-31 hypothetical protein EFP29_60 Enterococcus phage EF-P29 ORF8 3020 3178 159 + hypothetical protein WP_010749468 0 43 61 5.02E-04 hypothetical protein Enterococcus casseliflavus ORF9 3193 4158 966 + hypothetical protein YP_009036396 10 47 64 6.70E-70 hypothetical protein X878_0035 Enterococcus phage VD13 ORF10 4191 4730 540 + hypothetical protein ORF11 4727 5146 420 + hypothetical protein ORF12 5148 5348 201 + Enterococcus phage YP_009603964 3 58 70 8.41E-15 hypothetical protein IMEEF1 ORF13 6777 6971 195 + hypothetical protein ORF14 6976 7929 954 + hypothetical protein QBZ69248 1 50 70 7.56E-109 DNA primase Enterococcus phage vB_EfaS_Ef2.2 ORF15 7990 8268 279 + hypothetical protein ORF16 8268 9251 984 + hypothetical protein WP_088271390 10 36 53 1.69E-51 Rnl2 family RNA ligase Enterococcus wangshanyuanii ORF17 9253 9459 207 + hypothetical protein WP_002324739 0 65 76 6.90E-08 -

Heterozygous Colon Cancer-Associated Mutations of SAMHD1 Have Functional Significance

Correction BIOCHEMISTRY Correction for “Heterozygous colon cancer-associated muta- tions of SAMHD1 have functional significance,” by Matilda Rentoft, Kristoffer Lindell, Phong Tran, Anna Lena Chabes, Robert J. Buckland, Danielle L. Watt, Lisette Marjavaara, Anna Karin Nilsson, Beatrice Melin, Johan Trygg, Erik Johansson, and Andrei Chabes, which was first published April 11, 2016; 10.1073/pnas.1519128113 (Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113:4723–4728). The authors note that Fig. 2 appeared incorrectly. The cor- rected figure and its legend appear below. dCTP dTTP p<0.0001 p<0.0001 3 6 48 24 (dNTP/tot NTP) × 1000 (dNTP/tot NTP) × 1000 SAMHD1+/+ SAMHD1+/− SAMHD1−/− SAMHD1+/+ SAMHD1+/− SAMHD1−/− dATP dGTP p<0.0001 3 p=0.0003 4 2 1 26 (dNTP/tot NTP) × 1000 (dNTP/tot NTP) × 1000 SAMHD1+/+ SAMHD1+/− SAMHD1−/− SAMHD1+/+ SAMHD1+/− SAMHD1−/− Fig. 2. dNTP levels in mouse embryos are affected by SAMHD1 copy num- ber. dNTP levels were measured in E13.5 mouse embryos that were WT (33 embryos), lacking one copy of SAMHD1 (13 embryos), or lacking both copies of SAMHD1 (18 embryos). Results are presented in a boxplot where the central box spans the first to the third quartile, the whiskers represent minimum and maximum values, and the segment inside the box is the me- dian. Outliers are represented by circles. The significance value was calcu- lated by using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. Published under the PNAS license. Published online February 25, 2019. www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1902081116 4744 | PNAS | March 5, 2019 | vol. 116 | no. 10 www.pnas.org Downloaded by guest on October 2, 2021 Heterozygous colon cancer-associated mutations of SAMHD1 have functional significance Matilda Rentofta,b, Kristoffer Lindellb,1, Phong Tranb,1, Anna Lena Chabesb, Robert J. -

Adenosine Kinase Initiates the Major Route of Ribavirin Activation in A

Proc. Nati. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 75, No. 7, pp. 3042-3044, July 1978 Biochemistry Adenosine kinase initiates the major route of ribavirin activation in a cultured human cell line (lymphocyte/purine synthesis/purine excretion/futile cycle/deoxyadenosine kinase) R. C. WILLIS*, D. A. CARSONt, AND J. E. SEEGMILLER* * Department of Medicine, University of California at San Diego, La Jolla, California 92093; and t Division of Rheumatology, Department of Clinical Research, Scripps Clinic and Research Foundation, La Jolla, California 92037 Contributed by J. Edwin Seegmiller, February 27,1978 ABSTRACT Inhibition of IMP dehydrogenase (EC 1.2.1.14) transferase, EC 2.4.2.1) deficient line was derived from a pe- by ribavirin causes the normal human lymphoblast to excrete ripheral blood sample of a patient with immunodeficiency (9) increased amounts of newly formed purine into the culture the of Sly et al. (10). medium. In order for ribavirin to be active as an inhibitor of the by procedure dehydrogenase, this synthetic nucleoside must be phosphoryl- The cells were routinely cultured as described by Lever et ated. The effect of ribavirin on purine excretion has been de- al. (8). Prior to (14 hr) and during purine synthesis and excretion termined with a normal lymphoblast line, and with lymphoblast experiments, the cells were cultured in medium prepared with lines deficient in hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltansferase dialyzed 10% fetal calf serum. For studies with the Puo-phos- (IMP:pyrophosphate phosphoribosyl-transferase, EC 2.4.2.8), phorylase-deficient lymphoblast line, medium containing 0.1% in adenosine kinase (ATP:adenosine 5'-phosphotransferase, EC fetal calf serum, 0.005% transferrin, and 0.4% bovine serum 2.7.1.20), and in both hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase and adenosine kinase. -

Leeds Thesis Template

Roles and mechanisms of DNA repair factors and pathways in Maintaining Seed Quality Aaron James Barrett Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds Faculty of Biological Sciences School of Biology October, 2015 - ii - The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. The right of Aaron James Barrett to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. © 2015 The University of Leeds and Aaron James Barrett - iii - Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor Dr Christopher West for all his advice, support and incredible patience throughout my PhD. I would also like to express my gratitude to Dr Wanda Waterworth for all of her encouragement and guidance with my work. Thank-you to all of my colleagues at the University, in particular, Robbie Gillett, Thomas Lanyon-Hogg, Thomas Torode, Valerie Tennant, Vincent Agboh, Grace Hoystead, Jack Goode, Debs Roebuck. I would also like to thank Sue Marcus and all other members of the Knox, Foyer and Baker groups for their support. I owe a great debt to my friends outside the University for their support, including Brown, Broadley and all my friends from home. A big thank-you must also go to Maria and Dave Duxbury (particularly for driving me to the viva) and all associates of The Crown Inn for listening to my ramblings and to all of my incredibly supportive friends. -

Phyre 2 Results for P0A6D7

Email [email protected] Description P0A6D7 Thu Jan 5 11:02:54 GMT Date 2012 Unique Job 0244e86604702aa1 ID Detailed template information # Template Alignment Coverage 3D Model Confidence % i.d. Template Information PDB header:transferase Chain: B: PDB Molecule:shikimate kinase; 1 c3trfB_ 99.9 44 Alignment PDBTitle: structure of a shikimate kinase (arok) from coxiella burnetii Fold:P-loop containing nucleoside triphosphate hydrolases Superfamily:P-loop containing nucleoside triphosphate 2 d2iyva1 99.9 37 Alignment hydrolases Family:Shikimate kinase (AroK) Fold:P-loop containing nucleoside triphosphate hydrolases Superfamily:P-loop containing nucleoside triphosphate 3 d1e6ca_ 99.9 32 Alignment hydrolases Family:Shikimate kinase (AroK) Fold:P-loop containing nucleoside triphosphate hydrolases Superfamily:P-loop containing nucleoside triphosphate 4 d1viaa_ 99.9 29 Alignment hydrolases Family:Shikimate kinase (AroK) Fold:P-loop containing nucleoside triphosphate hydrolases Superfamily:P-loop containing nucleoside triphosphate 5 d1kaga_ 99.9 97 Alignment hydrolases Family:Shikimate kinase (AroK) PDB header:transferase Chain: D: PDB Molecule:shikimate kinase; 6 c2pt5D_ 99.9 36 Alignment PDBTitle: crystal structure of shikimate kinase (aq_2177) from aquifex aeolicus2 vf5 PDB header:transferase Chain: A: PDB Molecule:shikimate kinase; 7 c1zuiA_ 99.9 29 Alignment PDBTitle: structural basis for shikimate-binding specificity of helicobacter2 pylori shikimate kinase PDB header:transferase Chain: B: PDB Molecule:atsk2; 8 c3nwjB_ 99.9 24 Alignment