7. Integration with External Reality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction to Psychoanalysis

Introduction to Psychoanalysis The psychoanalytic movement has expanded and diversified in many directions over its one hundred year history. Introduction to Psychoanalysis: Contemporary Theory and Practice examines the contributions made by the various schools of thought, explaining the similarities and differences between Contemporary Freudian, Independent, Kleinian, Object Relations, Interpersonal, Self Psychological and Lacanian analysis. The authors address crucial questions about the role of psychoanalysis in psychiatry and look ahead to the future. The book is divided into two parts covering theory and practice. The first part considers theories of psychological development, transference and countertransference, dreams, defence mechanisms, and the various models of the mind. The second part is a practical introduction to psychoanalytic technique with specific chapters on psychoanalytic research and the application of psychoanalytic ideas and methods to treating psychiatric illness. Well referenced and illustrated throughout with vivid clinical examples, this will be an invaluable text for undergraduate and postgraduate courses in psychoanalysis and psychoanaltytic psychotherapy, and an excellent source of reference for students and professionals in psychiatry, psychology, social work, and mental health nursing. Anthony Bateman is Consultant Psychotherapist, St Ann’s Hospital, London and a member of the British Psychoanalytical Society. Jeremy Holmes is Consultant Psychotherapist and Psychiatrist, North Devon. Introduction to Psychoanalysis Contemporary theory and practice Anthony Bateman and Jeremy Holmes London and New York First published 1995 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2001. -

Jablonski MD, M.Sc, Psychoanalyst, (Sweden)

DEFINING BALINT WORK – IS THERE A HEARTLAND? AND WHICH ARE THE NEIGHBOURING COUNTRIES? by Henry Jablonski MD, M.Sc, psychoanalyst, (Sweden). Presented at the International Balint Federation Congress, Berlin (2003) and published in: Salinsky, J. and Otten, H. ( eds. ) (2003). The doctor, the patient and their well-being – world wide. Proceedings of the Thirteenth International Balint Congress Berlin 2003. The International Balint Federation. I will firstly try to say something about Balint work in the 21st century as a part of a humanistic, holistic approach to the medical profession. The ideas of Michael Balint for enhancing the professional capacity of the general practitioner have spread over the world during these 50 odd years since Balint met with his first groups of British GPs in the small conference rooms at 41, Portland Place off Oxford Circus in central London. They have inspired many doctors both in the somatic and psychiatric fields and a lot of group activities have been set up - and also vanished - bearing the name of Balint. In this paper, I attempt to discuss the essential ingredients of a Balint group. I discuss these issues from various perspectives: 1. The general purpose of a Balint group - the explicit goal and its consequences for the practical contents of work. 2. Some aspects of the boundaries and the "work contract" of the group 3. Demands on the group members 4. Demands on the group leader I propose a core definition: A Balint group consists of clinicians who meet, as equals and because each of them wish to do so. They meet on a regular basis over a long period of time to discuss and come to a better understanding of their own clinical work, their own meetings with their patients. -

War and the Practice of Psychotherapy: the UK Experience 1939–1960

Medical History, 2004, 48: 493–510 War and the Practice of Psychotherapy: The UK Experience 1939–1960 EDGAR JONES* During the Second World War, it is argued, ‘‘the neuroses of battle’’ not only deepened an understanding of ‘‘psychopathological mechanisms’’,1 but also created opportunities for the practice of psychotherapy, while its perceived efficacy led to a broader acceptance within medicine and society once peace had returned.2 This recognition is contrasted with the aftermath of the First World War when a network of outpatient clinics, set up by the Ministry of Pensions to treat veterans with shell shock, were closed within a few years in response to financial pressures and doubts about their therapeutic value. In the private sector, psychoanalysis under the leadership of Ernest Jones remained an idiosyncratic activity confined largely to the affluent middle classes of London.3 According to Gregorio Kohon, ‘‘it was strongly opposed by the general public, the Church, the medical and psychiatric establishment, and the press’’.4 The Medico-Psychological Clinic of London, originally set up in 1913, offered psychotherapy on three afternoons a week in premises at 30 Brunswick Square under the direction of Dr James Glover. However, it closed in 1923 after Glover and his brother Edward had both become psychoanalysts.5 As the First World War drew to a close, Maurice Craig helped to persuade Sir Ernest Cassel to fund a hospital for ‘Functional and Nervous Disorders’ at Penshurst, Kent, to treat neuroses in the civilian population.6 Although moved to permanent premises near Richmond, it remained small- scale and at the time no attempt was made to establish a network of similar institutions throughout the UK. -

Sándor Ferenczi's Multiple Confusions of Tongues and Their Influence On

The International Journal of Psychoanalysis ISSN: 0020-7578 (Print) 1745-8315 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ripa20 Sándor Ferenczi’s multiple confusions of tongues and their influence on psychoanalytical thinking Nicolas Evzonas To cite this article: Nicolas Evzonas (2018) Sándor Ferenczi’s multiple confusions of tongues and their influence on psychoanalytical thinking, The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 99:1, 230-247, DOI: 10.1080/00207578.2017.1399072 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/00207578.2017.1399072 View supplementary material Published online: 20 Mar 2018. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ripa20 INT J PSYCHOANAL, 2018 VOL. 99, NO. 1, 230–247 https://doi.org/10.1080/00207578.2017.1399072 Sándor Ferenczi’s multiple confusions of tongues and their influence on psychoanalytical thinking* Nicolas Evzonas CRPMS (Centre de Recherche Psychanalyse, Médecine et Société) [Centre for Research in Psychoanalysis, Medicine and Society] UFR of Psychoanalytic Studies Diderot University – Paris 7, Sorbonne Paris Cité University Group ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Using a poststructuralist model, this article explores the lecture Ferenczi; Freud; Trauma; given by Ferenczi and published under the title “Confusion of Sexual Abuse; Analytic Tongues between Adults and the Child—(The Language of Relationship; multilingualism Tenderness and Passion).” By initially focusing on the closed structure of the text, the author identifies two types of confusion of tongues that are closely interlinked: the confusion between adults and the child, and that between the analyst and the analysand. -

The Greening of Psychoanalysis

THE GREENING OF PSYCHOANALYSIS GoP_book.indb 1 22-May-17 9:40:56 AM Croagnes, 84490 Saint-Saturnin-lès-Apt, France, December 1997. Photo by Gregorio Kohon GoP_book.indb 2 22-May-17 9:40:56 AM THE GREENING OF PSYCHOANALYSIS André Green’s New Paradigm in Contemporary Theory and Practice Edited by Rosine Jozef Perelberg & Gregorio Kohon Foreword by Hannah Browne & Anna Streeruwitz KARNAC GoP_book.indb 3 22-May-17 9:40:56 AM First published in 2017 by Karnac Books 118 Finchley Road London NW3 5HT Copyright © 2017 by Rosine Jozef Perelberg & Gregorio Kohon. All contributors retain the copyright to their own chapters. The rights of the editors and contributors to be identified as the authors of this work have been asserted in accordance with §§ 77 and 78 of the Copyright Design and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A C.I.P. for this book is available from the British Library ISBN: 978–1–78220–562–3 Edited, designed, and produced by Communication Crafts Printed in Great Britain www.karnacbooks.com GoP_book.indb 4 22-May-17 9:40:56 AM To the memory of André Green 1927–2012 GoP_book.indb 5 22-May-17 9:40:56 AM GoP_book.indb 6 22-May-17 9:40:56 AM CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ix ABOUT THE EDITORS AND CONTRIBUTORS xi PREFACE xv FOREWORD xxi Introduction Rosine -

Three Testimonies About Meeting Michael Balint and His Ideas

The American Journal of Psychoanalysis, Vol. 62, No. 4, December 2002 ( 2002) THREE TESTIMONIES ABOUT MEETING MICHAEL BALINT AND HIS IDEAS Pierre Benoıˆt was a general practitioner who became a psychoanalyst without abandoning completely his medical practice. He was the family doctor of the Dormandi family and had several occasions to meet and have discussions with Michael Balint. Dr. Benoıˆt was very much interested in the Balint groups; he was leader of one of them, but not without trying to go further. Most of his ideas are expressed in a special number of the review Le Coq-He`ron n 95. This short testimony indicates in what direction he develops his thoughts. Dr. Benoıˆt submitted his contribution shortly before his death on September 19, 2001. Judith Dupont AMEETING WITH MICHAEL BALINT This is the account of my recollection of one of my meetings with Balint. This recollection may initiate some reflection about the object of the Balint method going beyond what is generally assigned to it: the analysis of the doctor–patient relationship. It is the recollection of a meeting with Balint, Mrs. Balint, Ginette and Emile Raimbaud, Marie-Ange and Jacques Gendrot, Sapir, and myself. The conversation run about the review of Balint’s famous book (The Doctor, His Patient and the Illness, 1957), just published in French. Seizing the opportunity of a moment of silence, Jacques Gendrot ad- dressed a question to Balint: “Please sir, why in your book you always talk about the Psychiatrist and not the Psychoanalyst as the leader of the group; after all, your reference is not psychiatry but actually psychoanalysis.” A long and uneasy silence followed, and it was Mrs. -

Piera Aulagnier, an Introduction: Some Elements of Her Intellectual Biography

Int J Psychoanal (2015) 96:1355–1369 doi: 10.1111/1745-8315.12409 Key Papers Piera Aulagnier, an introduction: Some elements of her intellectual biography Patrick Miller Member of Societ e Psychanalytique de Recherche et de Formation, 31 Quai des Grands Augustins, 75006 Paris, France – [email protected] The title of this paper, ‘Naissance d’un corps, origine d’une histoire’, bears witness to the importance that Piera Aulagnier granted to the dimension of history, and more precisely to the notion of historicization which she emphasized, and is related in some ways to that of the identificatory process in the development of personality. However, as far as her biography is concerned, we are left with scarce mate- rial, and the essence of it is mostly intellectual. It lies mainly in her books and articles where we can try and retrace the development and transformation of her thinking. It also resides in the Journals she created: first L’Inconscient (in collaboration with Jean Clavreul), then Topique which she launched in 1969 as sole chief editor, and in the part she actively played in the history of the French psychoanalytical movement, its controversies and schisms. First in the Societe Francßaise de Psychanalyse (SFP)1 where she trained and graduated and began publishing, then at the Ecole Freudienne de Paris founded in 1964 where she followed Lacan who had just been banned from being a training analyst by the IPA site visit committee when the SFP became an IPA Study Group, out of loyalty and solidarity because she thought the ban was unacceptable rather than out of support for his positions on training. -

Countertransference in Dermatology

Acta Derm Venereol 2016; Suppl 217: 18–21 REVIEW ARTICLE Countertransference in Dermatology Sylvie G. CONSOLI1 and Silla M. CONSOLI2 1Private practice, and 2Department of Psychiatry, Paris Descartes University, Paris, France The doctor–patient relationship in dermatology, as in ment. The patient is always hoping to meet the ideal all the fields of medicine, is not a neutral relationship, doctor and the doctor, similarly, would like his patient removed from affects. These affects take root in the so- to be an ideal patient (for example an always compliant ciocultural, professional, family and personal history of patient). both persons in the relationship. They underpin the psy- The doctor–patient relationship is an unequal chic reality of the patients, along with a variety of repre- relationship, the starting point of which is the request sentations, preconceived ideas, and fantasies concerning addressed by a suffering subject to a subject who dermatology, the dermatologists or the psychiatrists. possesses a particular expertise. Expressing a request Practitioners call these “countertransference feelings”, makes patients passive and dependent on the response with reference to the psychoanalytical concept of “coun- of others and their suffering constitutes an a priori tertransference”. These feelings come forward in a more handicap. In fact, things are actually much more com- or less conscious way and are active during the follow-up plex than this, because suffering also confers rights and of any patient: in fact they can facilitate or hinder such allows the person who is a victim to exert an influence a follow-up. Our purpose in focusing on this issue is to on his physician. -

In Psychotherapy of the Analytically Orientated Type. They Are

CORRESPONDENCE 283 in psychotherapy of the analytically orientated type. explanations must be considered. One is that treat They are encouraged to conceptualize and formulate ment has helped each group to different extents, the their patients' problems in the broadest sense; other is that treatment has harmed each group to treating them as members of a family group and differentextents.Clearlyseveralpossiblepermuta considering relevant cultural factors. Although by tions exist. no means abandoning the medical model, this is set The author considers that a pre-treatment measure in the much broader context of the whole person and is of secondary importance in answering the outcome his interaction with his fellow men. question.I suggestthatunlesssucha measureis As a medical student I found myself increasingly included we cannot decide whether a treatment has disenchanted with the dry narrow ‘¿scientific'view of been ‘¿moretherapeutic' than another or merely man. I was forced to the inescapable conclusion that ‘¿lessdamaging'. human suffering cannot be reduced to a series of A. V. P. MACKAY biochemical formulae, and unlike many I failed to MRCXeurochemical Pharmacology Unit, find patients who derived much benefit from medi Department of Pharmacology, cation, but found many whose suffering was in fact Medical School, Hills Road, worsened by misguided therapeutic zeal. It was for Cambridge CB2 2QD this reason that I chose psychiatry in the hope that here, at least, I could improve the quality of people's lives. It is therefore with growing disillusionment that IS PARENTHOOD TEACHABLE? I watch British psychiatry's love affair with medicine. If only the mountain had moved to Mohammed DEAR SIR, things might have been so different. -

9781782206521.Pdf

Ferenczi’s Influence on Contemporary Psychoanalytic Traditions This collection covers the great variety topics relevant for understanding the importance of Sándor Ferenczi and his influence on contemporary psychoanalysis. Pre-eminent Ferenczi scholars were solicited to contribute succinct reviews of their fields of expertise. The book is divided in five sections. ‘The historico-biographical’ describes Ferenczi’s childhood and student days, his marriage, brief analyses with Freud, his correspondences and contributions to the daily press in Budapest, exploration of his patients’ true identities, and a paper about his untimely death. ‘The development of Ferenczi’s ideas’ reviews his ideas before his first encounter with psychoanalysis, his relationship with peers, friendship with Groddeck, emancipation from Freud, and review of the importance of his Clinical Diary. The third section reviews Ferenczi’s clinical concepts and work: trauma, unwelcome child, wise baby, identification with aggressor, mutual analysis, and many others. In ‘Echoes’, we follow traces of Ferenczi’s influence on virtually all traditions in contemporary psychoanalysis: interpersonal, independent, Kleinian, Lacanian, relational, etc. Finally, there are seven ‘application’ chapters about Ferenczi’s ideas and the issues of politics, gender and development. Aleksandar Dimitrijević, PhD, is interim professor of psychoanalysis and clinical psychology at the International Psychoanalytic University, Berlin, Germany. He is a member of the Belgrade Psychoanalytical Society (IPA) and Faculty at the Serbian Association of Psychoanalytic Psychotherapists (EFPP), and the editor or co-editor of ten books or special journal issues, as well as author of many conceptual and empirical papers, about attachment theory and research, psychoanalytic education, psychoanalysis and the arts. Gabriele Cassullo is a psychologist, psychotherapist, doctor in research in human sciences and interim professor in psychology at the Department of Psychology, University of Turin. -

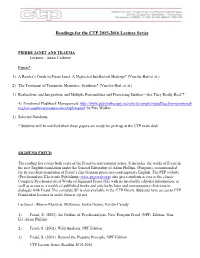

Readings for the CTP 2015-2016 Lecture Series

Readings for the CTP 2015-2016 Lecture Series PIERRE JANET AND TRAUMA Lecturer - Adam Crabtree Papers*: 1) A Reader’s Guide to Pierre Janet: A Neglected Intellectual Heritage* (Van der Hart et al.) 2) The Treatment of Traumatic Memories: Synthesis* (Van der Hart, et al.) 3) Realization, and Integration; and Multiple Personalities and Possessing Entitles—Are They Really Real?* 4) Emotional Flashback Management: http://www.psychotherapy.net/article/complex-ptsd#section-emotional- neglect:-a-primary-cause-of-complex-ptsd by Pete Walker 5) Selected Handouts. * Students will be notified when these papers are ready for pick-up at the CTP main desk SIGMUND FREUD The reading list covers both years of the Freud lecture/seminar series. It includes the works of Freud in the new English translation under the General Editorship of Adam Phillips, (Penguin), recommended for its excellent translation of Freud’s fine German prose into contemporary English. The PEP website (Psychoanalytic Electronic Publishing- www.pep-web.org) also gives students access to the classic Complete Psychoanalytical Works of Sigmund Freud (SE) with its invaluable editorial information; as well as access to a wealth of published books and articles by later and contemporary clinicians in dialogue with Freud. The complete SE is also available in the CTP library. Students have access to CTP Foundation lectures in audio form at ctp.net. Lecturers - Sharon MacIssac McKenna, Jackie Herner, Kristin Casady 1) Freud, S. (2003) An Outline of Psychoanalysis. New Penguin Freud (NPF) Edition, Gen. Ed. Adam Phillips 2) Freud, S. (2002). Wild Analysis. NPF Edition 3) Freud, S. (2003). Beyond the Pleasure Principle. -

9781138899056.Pdf

“The Unobtrusive Relational Analyst draws on the history of psychoanalysis so as to create its bright future. In its pages the contributions of Freud and British Object Relations theory open to the Relational Turn and to a model of 21st century practice that is integrative and innovative. Through multiple, extended vignettes Grossmark illustrates his clinical position of gentle presence with a remarkable openness and clarity, emphasizing the role of action in the talking cure and the importance of engagement in a process that takes patient and analyst, and will also take the reader, to undiscovered areas of psychic life and living. If this sounds different and new to you, you’re right, it is! Transcending parochial divisions, Grossmark creates from varied facets of analytic theory an elegant and eloquent original synthesis that is at once ‘in the tradition’ and its forward edge.” —Bruce Reis, Ph.D., NYU Postdoctoral Program in Psychotherapy and Psychoanalysis, & the Institute for Psychoanalytic Training and Research “In this wonderfully innovative book, Robert Grossmark shows us how to work with the most difficult patients we encounter, those whose words are empty, whose feelings are dead and who are unable to relate as whole objects or to make a life they can own. Calling on a wide variety of theories from many different schools of thought, Grossmark has woven a conceptual net that captures his unique way of ‘companioning’ these people whom he describes in such loving and dramatic detail. A companion is someone who travels along with you and shares your bread. I can think of no better companion for a deep psychoanalytic voyage than Robert Grossmark.