Managing Natural Resources in Fragile States in Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNHCR Republic of Congo Fact Sheet

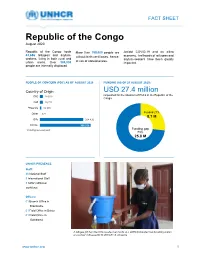

FACT SHEET Republic of the Congo August 2020 Republic of the Congo hosts More than 155,000 people are Amidst COVID-19 and an ailing 43,656 refugees and asylum- without birth certificates, hence, economy, livelihoods of refugees and seekers, living in both rural and asylum-seekers have been greatly at risk of statelessness. urban areas. Over 304,000 impacted. people are internally displaced PEOPLE OF CONCERN (POC) AS OF AUGUST 2020 FUNDING (AS OF 25 AUGUST 2020) Country of Origin USD 27.4 million requested for the situation of PoCs in the Republic of the DRC 20 810 Congo CAR 20,722 *Rwanda 10 565 Funded 27% Other 421 8.1 M IDPs 304 430 TOTAL: 356 926 * Including non-exempted Funding gap 73% 25.8 M UNHCR PRESENCE Staff: 46 National Staff 9 International Staff 8 IUNV (affiliated workforce) Offices: 01 Branch Office in Brazzaville 01 Field Office in Betou 01 Field Office in Gamboma A refugee girl from the DRC washes her hands at a UNHCR-installed handwashing station at a school in Brazzaville © UNHCR / S. Duysens www.unhcr.org 1 FACT SHEET > Republic of the Congo / August 2020 Working with Partners ■ Aligning with the Global Compact on Refugees (GCR), UNHCR in the Republic of the Congo (RoC) has diversified its partnership base to include five implementing partners, comprising local governmental and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), as well as international NGOs. ■ The National Committee for Assistance to Refugees (CNAR), is UNHCR’s main governmental partner, covering general refugee issues, particularly Refugee Status Determination (RSD). Other specific governmental partners include the Ministry of Social and Humanitarian Affairs (MASAH), the Ministries of Justice and Interior (for judicial issues and policies on issues related to statelessness and civil status registration), and the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH). -

Policy Paper Gb

Concepts and Dilemmas of State Building in Fragile Situations FROM FRAGILITY TO RESILIENCE OECD/DAC DISCUSSION PAPER Concepts and Dilemmas of State Building in Fragile Situations FROM FRAGILITY TO RESILIENCE ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT The OECD is a unique forum where the governments of 30 democracies work together to address the economic, social and environmental challenges of globalisation.The OECD is also at the forefront of efforts to understand and to help governments respond to new developments and concerns, such as corporate governance, the information economy and the challenges of an ageing population. The Organisation provides a setting where governments can compare policy experiences, seek answers to common problems, identify good practice and work to co-ordinate domestic and international policies. The OECD member countries are: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Korea, Luxembourg, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, the Slovak Republic, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom and the United States. The Commission of the European Communities takes part in the work of the OECD. OECD Publishing disseminates widely the results of the Organisation's statistics gathering and research on economic, social and environmental issues, as well as the conventions, guidelines and standards agreed by its members. Off-print of the Journal on Development 2008, Volume 9, No. 3 Also available in French FOREWORD Foreword Today it is widely accepted that development, peace and stability require effective and legitimate states able to fulfil key international responsibilities and to provide core public goods and services, including security. -

Drivers of Fragility: What Makes States Fragile?

Working Paper for Discussion Only Not UK Government Policy DEPARTMENT FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT PRDE WORKING PAPER NO. 7 DRIVERS OF FRAGILITY: WHAT MAKES STATES FRAGILE? April 2005 Claire Vallings and Magüi Moreno-Torres This Working Paper is part of a series prepared by the Poverty Reduction in Difficult Environments (PRDE) team in the Department for International Development’s Policy Division. It represents solely the views of those involved in its drafting and does not necessarily represent official policy. Please send all feedback to Claire Vallings at [email protected]. 0 Drivers of Fragility: What Makes States Fragile? Contents Executive summary..........................................................................................2 I. Introduction: what drives fragility? .....................................................4 II. The central driver of fragility: weak political institutions .....................7 A. What makes the institutional set-up weak? ......................................... 8 B. How does an unchecked executive relate to weak institutions?........ 10 C. How does limited political participation relate to weak institutions? .. 11 III. Other drivers of fragility................................................................13 A. Economic development ..................................................................... 14 B. Natural resources .............................................................................. 17 C. Violent conflict .................................................................................. -

Democratic Republic of Congo Constitution

THE CONSTITUTION OF THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO, 2005 [1] Table of Contents PREAMBLE TITLE I GENERAL PROVISIONS Chapter 1 The State and Sovereignty Chapter 2 Nationality TITLE II HUMAN RIGHTS, FUNDAMENTAL LIBERTIES AND THE DUTIES OF THE CITIZEN AND THE STATE Chapter 1 Civil and Political Rights Chapter 2 Economic, Social and Cultural Rights Chapter 3 Collective Rights Chapter 4 The Duties of the Citizen TITLE III THE ORGANIZATION AND THE EXERCISE OF POWER Chapter 1 The Institutions of the Republic TITLE IV THE PROVINCES Chapter 1 The Provincial Institutions Chapter 2 The Distribution of Competences Between the Central Authority and the Provinces Chapter 3 Customary Authority TITLE V THE ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COUNCIL TITLE VI DEMOCRACY-SUPPORTING INSTITUTIONS Chapter 1 The Independent National Electoral Commission Chapter 2 The High Council for Audiovisual Media and Communication TITLE VII INTERNATIONAL TREATIES AND AGREEMENTS TITLE VIII THE REVISION OF THE CONSTITUTION TITLE IX TRANSITORY AND FINAL PROVISIONS PREAMBLE We, the Congolese People, United by destiny and history around the noble ideas of liberty, fraternity, solidarity, justice, peace and work; Driven by our common will to build in the heart of Africa a State under the rule of law and a powerful and prosperous Nation based on a real political, economic, social and cultural democracy; Considering that injustice and its corollaries, impunity, nepotism, regionalism, tribalism, clan rule and patronage are, due to their manifold vices, at the origin of the general decline -

Profile of Internal Displacement : Sierra Leone

PROFILE OF INTERNAL DISPLACEMENT : SIERRA LEONE Compilation of the information available in the Global IDP Database of the Norwegian Refugee Council (as of 15 October, 2003) Also available at http://www.idpproject.org Users of this document are welcome to credit the Global IDP Database for the collection of information. The opinions expressed here are those of the sources and are not necessarily shared by the Global IDP Project or NRC Norwegian Refugee Council/Global IDP Project Chemin Moïse Duboule, 59 1209 Geneva - Switzerland Tel: + 41 22 799 07 00 Fax: + 41 22 799 07 01 E-mail : [email protected] CONTENTS CONTENTS 1 PROFILE SUMMARY 6 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 CAUSES AND BACKGROUND OF DISPLACEMENT 9 BACKGROUND TO THE CONFLICT 9 CHRONOLOGY OF SIGNIFICANT EVENTS SINCE INDEPENDENCE (1961 - 2000) 9 HISTORICAL OUTLINE OF THE FIRST EIGHT YEARS OF CONFLICT (1991-1998) 13 CONTINUED CONFLICT DESPITE THE SIGNING OF THE LOME PEACE AGREEMENT (JULY 1999-MAY 2000) 16 PEACE PROCESS DERAILED AS SECURITY SITUATION WORSENED DRAMATICALLY IN MAY 2000 18 RELATIVELY STABLE SECURITY SITUATION SINCE SIGNING OF CEASE-FIRE AGREEMENT IN ABUJA ON 10 NOVEMBER 2000 20 CIVIL WAR DECLARED OVER FOLLOWING THE FULL DEPLOYMENT OF UNAMSIL AND THE COMPLETION OF DISARMAMENT (JANUARY 2002) 22 REGIONAL EFFORTS TO MAINTAIN PEACE IN SIERRA LEONE (2002) 23 SIERRA LEONEANS GO TO THE POLLS TO RE-ELECT AHMAD TEJAN KABBAH AS PRESIDENT (MAY 2002) 24 SIERRA LEONE’S SPECIAL COURT AND TRUTH AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION START WORK (2002-2003) 25 MAIN CAUSES OF DISPLACEMENT 28 COUNTRYWIDE DISPLACEMENT -

Productive and Decent Work for Youth in the Mano River Union: Guinea

UNIDO AFRICAN UNION YEN UNOWA Productive and Decent Work for Youth in the Mano River Union: Guinea, Liberia, Sierra Leone and in Côte d’Ivoire 4.5 million youth need employment: An agenda for a multi-stakeholder programme ISSUES PAPER February 2007 CONTENTS Introduction I. Youth Employment - a stimulus to peace and economic stability II. What has been achieved? • Job creation for youth: Past and on-going efforts by Governments and various stakeholders • Gaps and missing links III. The Way Ahead • Balancing demand and supply • Exploring new productive opportunities • Best practices IV. Funding Mechanisms Annexes a. Youth unemployment rates in MRU and Côte d’Ivoire b. Policy initiatives: - Inclusion of youth employment in PRSPs/budgets - Inclusion of youth in national employment policies and other initiatives c. Examples of youth-targeted programmes to increase demand for labour d. Examples of youth-targeted programmes to improve the supply of labour e. Proposed initiatives in the Mano River Union and in Côte d’Ivoire Introduction This Issues Paper is intended to guide the discussions at the UNIDO/African Union (AU) High-Level Consultative Meeting, organized in cooperation with The United Nations Office for West Africa (UNOWA), and the United Nations Secretary-General’s Youth Employment Network (YEN) on Productive and Decent Work for Youth, in the countries of the Mano River Union (MRU): Sierra Leone, Liberia, Guinea, and in Côte d’Ivoire. The Issues Paper: Addresses the urgent need to create employment for 4.5 million youth aged between -

Why Is the African Economic Community Important? Mr

House Committee on Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Africa, Global Health, Global Human Rights, and International Organizations Hearing on “Will there be an African Economic Community?” January 9, 2014 Amadou Sy, Senior Fellow, Africa Growth Initiative, the Brookings Institution Chairman Smith, Ranking Member Bass, and Members of the Subcommittee, I would like to take this opportunity to thank you for convening this important hearing to discuss Africa’s progress towards establishing an economic community. I appreciate the invitation to share my views on behalf of the Africa Growth Initiative at the Brookings Institution. The Africa Growth Initiative at the Brookings Institution delivers high-quality research on issues of economic growth and development from an African perspective to better inform policy research. I have recently joined AGI from the International Monetary Fund’s where I led or participated in a number of missions to Africa over the past 15 years. Why is the African Economic Community Important? Mr. Chairman, before we start answering the main question, “Will there be an Africa Economic Community?” it is important to look at the reasons why a regionally integrated Africa is beneficial to African nations as well as the United States. In spite of its remarkable economic performance over the past decade, Africa needs to grow faster in order to transform its economy and create the resources needed to reduce poverty. Over the past 10 years, sub-Saharan Africa’s real GDP grew by 5.6 percent per year, a much faster rate than the world economy, which grew by 3.2 percent. At this rate of 5.6 percent, the region should double the size of its economy in about 13 years. -

Fragile Contexts in 2018

CHAPTER ELEVEN Leaving No Fragile State and No One Behind in a Prosperous World: A New Approach Landry Signé undreds of millions of people are left behind in fragile states despite the efforts of the international community to make progress on development Hand alleviate conflict. People in fragile states are victim to persistent poverty,1 enduring violence, poor public facilities, deteriorating infrastructure,2 limited civil and political liberties,3 deteriorating social conditions,4 minimal to nonexistent economic growth,5 and, often, humanitarian crises.6 Research and policies on state fragility build on concepts of limited state capacity, legitimacy, insecurity, stability and socioeconomic, demographic, human development, environmental, humanitarian, and gender contexts to determine states’ apparent effectiveness or ineffectiveness in fulfilling the role of the state. Within this -con text, fragility has become a catch- all concept encompassing fragile states, weak states, failed states, collapsing or decaying states, conflict- affected countries, post- conflict countries, brittle states, and states with limited legitimacy, author- ity, capacity, governance, security, and socioeconomic and human development. 1. Collier (2007). 2. Rotberg (2011). 3. Bah (2012). 4. Van de Walle (2004). 5. Brainard and Chollet (2007). 6. Nwozor (2018). The author would like to express his sincere appreciation to Payce Madden, Genevieve Jesse, and Elise El Nouchi, who contributed to the research, data analysis, fact- checking, and visual elements of this chapter. 239 Kharas-McArthur-Ohno_Leave No One Behind_i-xii_1-340.indd 239 9/6/19 1:57 PM 240 Landry Signé When used without conceptual clarification and contextual consideration, as is often the case, the concept of fragility lacks usefulness for policymakers, as the various types, drivers, scopes, levels, and contexts of fragility require differ- ent responses. -

Republic of the Congo

UNITED NATIONS CONSOLIDATED INTER-AGENCY APPEAL FOR THE REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO JANUARY – DECEMBER 2000 November 1999 UNITED NATIONS For additional copies, please contact: UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs Complex Emergency Response Branch (CER-B) Palais des Nations 8-14 Avenue de la Paix CH - 1211 Geneva, Switzerland Tel.: (41 22) 917.1972 Fax: (41 22) 917.0368 E-Mail: [email protected] This document is also available on http://www.reliefweb.int/ iii iv TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY…………………………………………………………………………………………. 1 Table 1: Total Funding Requirement – By Sector and Appealing 2 Agency…………...… CONTEXT………………………………………………………………………………………….. 3 Table 2: Effects of the Wars 1997 – 4 1999……..………………………………...………. 5 Table 3: ROC 810,000 Displaced and Returned Persons by Urgan or Rural Origin… POLITICS, ECONOMY AND SECURITY……………………………………………………………. 5 Analysis, Scenarios and Response…….………………………………………………….. 7 A COMMON HUMANITARIAN ACTION PLAN (CHAP) TWO SCENARIOS………………………… 7 SCENARIO I……………………………………………………………………………………. 8 Table 4: 810,000 Displaced and Returned Persons by Place of Origin and Present Location……………………………………………………………………...…… 9 SCENARIO II…………………………………………………………………………………… 9 LINKING RELIEF AND DEVELOPMENT……………………………………………………………. 11 MONITORING……………………………………………………………………………………… 11 STATEMENT OF HUMANITARIAN PRINCIPLES……………………………………………………. 13 SECTORS TO ADDRESS, AND OBJECTIVES, FOR JANUARY – DECEMBER 2000………………. 13 Table 5: Individual Project Activities by 15 Sector……………………………………………. Table 6: Individual Project Activities by Appealing -

The Mano River Union Trade Facilitation Study

REQUEST FOR EXPRESSIONS OF INTEREST (CONSULTING SERVICES) AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK NEPAD, REGIONAL INTEGRATION AND TRADE DEPARTMENT ATR B, 5th Floor 13 Avenue de Ghana, B.P. 323 - 1002 Tunis-Belvédère, Tunisia The Mano River Union Trade Facilitation Study The African Development Bank invites Consultants to express their interest in undertaking a Trade Facilitation Needs Assessment Study for the Mano River Union (MRU). The services included under this assignment are: A review of relevant background materials on the MRU, including the Treaty and its Protocols that define the legal framework, principles and polices for intra-union trade; A review of state of trade and integration in the MRU; the trends, patterns of trade flows, including informal trade; Identification trade policy handicaps, including human; institutional; non-tariff barriers that hinder movements of goods, services and persons - Rules of Origin, Customs Procedures, Technical Barriers, Regulations and administrative measures etc. A review of relevant trade facilitation regulations; Assessment of critical trade facilitation needs, especially in the areas of transport and transit corridor facilitation, border operations and management, legal issues associated with transit border management; customs procedures, systems connectivity and automation, the legal/regulatory frameworks, This should also be linked to the new concept of the MRU growth triangle programme; Assessment of and situate the MRU roles in the overall trade policy and trade facilitation process vis-à-vis -

Effectiveness of Democracy-Support in "Fragile States": a Review

Discussion Paper 1/2013 Effectiveness of Democracy-Support in "Fragile States": a Review Kimana Zulueta-Fülscher Effectiveness of democracy-support in “fragile states”: a review Kimana Zulueta-Fülscher Bonn 2013 Discussion Paper / Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik ISSN 1860-0441 Die deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data is available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de. ISBN 978-3-88985-624-1 Dr Kimana Zulueta-Fülscher, German Development Institute / Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE), Senior Researcher, Department “Governance, Statehood, Security” E-mail: [email protected] © Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik gGmbH Tulpenfeld 6, 53113 Bonn +49 (0)228 94927-0 +49 (0)228 94927-130 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.die-gdi.de Abstract Over the past decade, the interest in aid effectiveness has grown exponentially, with a proliferation of both praxis-oriented evaluations and academic studies. At the same time, the rising interest in “fragile states” has prompted the aid-effectiveness literature to focus its attention on this category of states. Parallel to the development of the aid-effectiveness literature, the literature on the impact of specific development-aid sectors has also surged. The increasing number of analyses on the impact of external policies contributing to processes of political transformation (democratisation or stabilisation) has been remarkable. This discussion paper thematises the growing literature on both fragility and the effectiveness of democracy support, with a special focus on the quantitative literature. -

Country Coding Units

INSTITUTE Country Coding Units v11.1 - March 2021 Copyright © University of Gothenburg, V-Dem Institute All rights reserved Suggested citation: Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, Jan Teorell, and Lisa Gastaldi. 2021. ”V-Dem Country Coding Units v11.1” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. Funders: We are very grateful for our funders’ support over the years, which has made this ven- ture possible. To learn more about our funders, please visit: https://www.v-dem.net/en/about/ funders/ For questions: [email protected] 1 Contents Suggested citation: . .1 1 Notes 7 1.1 ”Country” . .7 2 Africa 9 2.1 Central Africa . .9 2.1.1 Cameroon (108) . .9 2.1.2 Central African Republic (71) . .9 2.1.3 Chad (109) . .9 2.1.4 Democratic Republic of the Congo (111) . .9 2.1.5 Equatorial Guinea (160) . .9 2.1.6 Gabon (116) . .9 2.1.7 Republic of the Congo (112) . 10 2.1.8 Sao Tome and Principe (196) . 10 2.2 East/Horn of Africa . 10 2.2.1 Burundi (69) . 10 2.2.2 Comoros (153) . 10 2.2.3 Djibouti (113) . 10 2.2.4 Eritrea (115) . 10 2.2.5 Ethiopia (38) . 10 2.2.6 Kenya (40) . 11 2.2.7 Malawi (87) . 11 2.2.8 Mauritius (180) . 11 2.2.9 Rwanda (129) . 11 2.2.10 Seychelles (199) . 11 2.2.11 Somalia (130) . 11 2.2.12 Somaliland (139) . 11 2.2.13 South Sudan (32) . 11 2.2.14 Sudan (33) .