Why Is the African Economic Community Important? Mr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNHCR Republic of Congo Fact Sheet

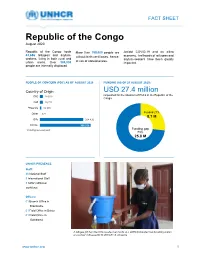

FACT SHEET Republic of the Congo August 2020 Republic of the Congo hosts More than 155,000 people are Amidst COVID-19 and an ailing 43,656 refugees and asylum- without birth certificates, hence, economy, livelihoods of refugees and seekers, living in both rural and asylum-seekers have been greatly at risk of statelessness. urban areas. Over 304,000 impacted. people are internally displaced PEOPLE OF CONCERN (POC) AS OF AUGUST 2020 FUNDING (AS OF 25 AUGUST 2020) Country of Origin USD 27.4 million requested for the situation of PoCs in the Republic of the DRC 20 810 Congo CAR 20,722 *Rwanda 10 565 Funded 27% Other 421 8.1 M IDPs 304 430 TOTAL: 356 926 * Including non-exempted Funding gap 73% 25.8 M UNHCR PRESENCE Staff: 46 National Staff 9 International Staff 8 IUNV (affiliated workforce) Offices: 01 Branch Office in Brazzaville 01 Field Office in Betou 01 Field Office in Gamboma A refugee girl from the DRC washes her hands at a UNHCR-installed handwashing station at a school in Brazzaville © UNHCR / S. Duysens www.unhcr.org 1 FACT SHEET > Republic of the Congo / August 2020 Working with Partners ■ Aligning with the Global Compact on Refugees (GCR), UNHCR in the Republic of the Congo (RoC) has diversified its partnership base to include five implementing partners, comprising local governmental and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), as well as international NGOs. ■ The National Committee for Assistance to Refugees (CNAR), is UNHCR’s main governmental partner, covering general refugee issues, particularly Refugee Status Determination (RSD). Other specific governmental partners include the Ministry of Social and Humanitarian Affairs (MASAH), the Ministries of Justice and Interior (for judicial issues and policies on issues related to statelessness and civil status registration), and the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH). -

Côte D'ivoire

CÔTE D’IVOIRE COI Compilation August 2017 United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Regional Representation for West Africa - RSD Unit UNHCR Côte d’Ivoire UNHCR Regional Representation for West Africa - RSD Unit UNHCR Côte d’Ivoire Côte d’Ivoire COI Compilation August 2017 This report collates country of origin information (COI) on Côte d’Ivoire up to 15 August 2017 on issues of relevance in refugee status determination for Ivorian nationals. The report is based on publicly available information, studies and commentaries. It is illustrative, but is neither exhaustive of information available in the public domain nor intended to be a general report on human-rights conditions. The report is not conclusive as to the merits of any individual refugee claim. All sources are cited and fully referenced. Users should refer to the full text of documents cited and assess the credibility, relevance and timeliness of source material with reference to the specific research concerns arising from individual applications. UNHCR Regional Representation for West Africa Immeuble FAALO Almadies, Route du King Fahd Palace Dakar, Senegal - BP 3125 Phone: +221 33 867 62 07 Kora.unhcr.org - www.unhcr.org Table of Contents List of Abbreviations .............................................................................................................. 4 1 General Information ....................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Historical background ............................................................................................ -

A Safety Net for Africa: Towards an African Monetary Fund?

Robert Triffin International A watch on the international financial and monetary system A SAFETY NET FOR AFRICA: TOWARDS AN AFRICAN MONETARY FUND? Dominique De Rambures, Alfonso Iozzo, Annamaria Viterbo After the Second World War, the establishment of the United Nations was completed, in the financial area, with those of the IMF for financing the balances of payments, and the World Bank for financing infrastructure and investment projects. The European Union has created the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) for financing the member States who are dealing with payment problems, which can be compared to the IMF, and the EIB for financing the investment project which can be compared to the World Bank. China numerous entities for financing investments, such as the China Development Bank, Export-Import Bank, and many funds and development banks dedicated to a specific purpose such as the ABII (Asia Bank for Infrastructures and Investments) to support the OBOR policy (One Belt One Road, i.e. the New Silk Roads). Beyond their aim of financing investments, China uses these financial organizations and others such as the sovereign fund, China Investment Corp., and the state banks, for buying government bonds to countries such as Greece and Portugal during the 2008 crisis, that are dealing with payment problems. The African Development Bank grants loans to finance infrastructure and investment projects, but Africa has no financial institution such as the IMF or the ESM. Why should Africa build up a financial institution of this kind while the Africain countries have so far called upon the IMF for their financial needs? - the IMF does initiate a financial package but does not provide the whole amount of funds needed. -

Institutionalising Pan-Africanism Transforming African Union Values and Principles Into Policy and Practice Tim Murithi

Institutionalising Pan-Africanism Transforming African Union values and principles into policy and practice Tim Murithi ISS Paper 143 • June 2007 Price: R15.00 Introduction translated into protocols, treaties and institutions. The discussion concludes with policy recommendations. The African Union has emerged as a home-grown initiative by which the African people will be able to Defining Pan-Africanism effectively take the destiny of their continent into their own hands. In this paper the creation of the AU as the The general assumption is that the process of continental institutionalisation of the ideals of Pan-Africanism will integration began with an extraordinary summit of be assessed. The underlying purpose of the creation the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) which was of the AU is to promote solidarity, cooperation and convened in Sirte, Libya, in 1999. But in fact the support among African countries and peoples so as to process began with the Pan-African movement and address the catalogue of problems they face. its demand for greater solidarity among the peoples of Africa. Therefore an understanding of the emergence Some observers and commentators of the AU should start with the evolution question whether the AU is a valid of the Pan-African movement. A review undertaking at this time, or whether it of the objectives and aspirations of Pan- is just another ambitious campaign by An understanding Africanism provides a foundation for self-seeking leaders to distract attention a critical assessment of the creation of from other, more pressing problems of the emergence the AU and its prospects for promoting on the continent. -

Is SACU Ready for a Monetary Union?

OCCASIONAL PAPER NO 1 4 3 Economic Diplomacy Programme A p r i l 2 0 1 3 Is SACU Ready for a Monetary Union? Hilary Patroba & Morisho Nene s ir a f f A l a n o ti a rn e nt f I o te tu sti n In rica . th Af hts Sou sig al in Glob African perspectives. About SAIIA The South African Institute of International Affairs (SAIIA) has a long and proud record as South Africa’s premier research institute on international issues. It is an independent, non-government think-tank whose key strategic objectives are to make effective input into public policy, and to encourage wider and more informed debate on international affairs with particular emphasis on African issues and concerns. It is both a centre for research excellence and a home for stimulating public engagement. SAIIA’s occasional papers present topical, incisive analyses, offering a variety of perspectives on key policy issues in Africa and beyond. Core public policy research themes covered by SAIIA include good governance and democracy; economic policymaking; international security and peace; and new global challenges such as food security, global governance reform and the environment. Please consult our website www.saiia.org.za for further information about SAIIA’s work. A b o u t t h e e C o N o M I C D I P L o M A C Y P r o g r amm e SAIIA’s Economic Diplomacy (EDIP) Programme focuses on the position of Africa in the global economy, primarily at regional, but also at continental and multilateral levels. -

Democratic Republic of Congo Constitution

THE CONSTITUTION OF THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO, 2005 [1] Table of Contents PREAMBLE TITLE I GENERAL PROVISIONS Chapter 1 The State and Sovereignty Chapter 2 Nationality TITLE II HUMAN RIGHTS, FUNDAMENTAL LIBERTIES AND THE DUTIES OF THE CITIZEN AND THE STATE Chapter 1 Civil and Political Rights Chapter 2 Economic, Social and Cultural Rights Chapter 3 Collective Rights Chapter 4 The Duties of the Citizen TITLE III THE ORGANIZATION AND THE EXERCISE OF POWER Chapter 1 The Institutions of the Republic TITLE IV THE PROVINCES Chapter 1 The Provincial Institutions Chapter 2 The Distribution of Competences Between the Central Authority and the Provinces Chapter 3 Customary Authority TITLE V THE ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COUNCIL TITLE VI DEMOCRACY-SUPPORTING INSTITUTIONS Chapter 1 The Independent National Electoral Commission Chapter 2 The High Council for Audiovisual Media and Communication TITLE VII INTERNATIONAL TREATIES AND AGREEMENTS TITLE VIII THE REVISION OF THE CONSTITUTION TITLE IX TRANSITORY AND FINAL PROVISIONS PREAMBLE We, the Congolese People, United by destiny and history around the noble ideas of liberty, fraternity, solidarity, justice, peace and work; Driven by our common will to build in the heart of Africa a State under the rule of law and a powerful and prosperous Nation based on a real political, economic, social and cultural democracy; Considering that injustice and its corollaries, impunity, nepotism, regionalism, tribalism, clan rule and patronage are, due to their manifold vices, at the origin of the general decline -

New Records of the Togo Toad, Sclerophrys Togoensis, from South-Eastern Ivory Coast

Herpetology Notes, volume 12: 501-508 (2019) (published online on 19 May 2019) New records of the Togo Toad, Sclerophrys togoensis, from south-eastern Ivory Coast Basseu Aude-Inès Gongomin1, N’Goran Germain Kouamé1,*, and Mark-Oliver Rödel2 Abstract. Reported are new records of the forest toad, Sclerophrys togoensis, from south-eastern Ivory Coast. A small population was found in the rainforest of Mabi and Yaya Classified Forests. These forests and Taï National Park in the western part of the country are the only known and remaining Ivorian habitats of this species. Sclerophrys togoensis is confined to primary and slightly degraded rainforest. Known sites should be urgently and effectively protected from further forest loss. Keywords. Amphibia, Anura, Bufonidae, Conservation, Distribution, Mabi/Yaya Classified Forests, Upper Guinea forest Introduction In Ivory Coast the known records of S. togoensis are from the Cavally and Haute Dodo Classified Forests The toad Sclerophrys togoensis (Ahl, 1924) has been (Rödel and Branch, 2002), and the Taï National Park described from Bismarckburg in Togo (Ahl, 1924). Apart and its surroundings (e.g. Ernst and Rödel, 2006; Hillers from a parasitological study (Bourgat, 1978), no recent et al., 2008), all situated in the westernmost part of the records are known from that country (Ségniagbeto et al., country (Fig. 1). During a decade of conflict, both 2007; Hillers et al., 2009). Further records have been classified forests have been deforested (P.J. Adeba, pers. published from southern Ghana (Kouamé et al., 2007; comm.), thus restricting the species known Ivorian range Hillers et al., 2009), western Ivory Coast (e.g. -

Currency Union As a Panacea for Ills in Africa: a New Institutional Framework and Theoretical Consideration

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Currency Union as a Panacea for ills in Africa: A New Institutional Framework and Theoretical Consideration Abban, Stanley Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology 11 December 2020 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/105459/ MPRA Paper No. 105459, posted 25 Jan 2021 20:11 UTC 1.0 INTRODUCTION A currency union is a union to which two or more countries agree to surrender their monetary sovereignty to adopt an official currency issued by a Central Bank tasked with formulating and implementing monetary policy. Currency union came to light when there was a need for choosing a suitable exchange rate regime as an improvement on the fixed exchange rate. Comparatively, currency union is superlative to fixed exchange rate due to equalization of price through the laid down nominal convergence criteria and the introduction of a common currency to ensure greater transparency in undertaking transactions (Rose, 2000; Abban, 2020a). Currency union is touted to emanate several gains and has the potential to be disastrous based on the conditionality among member-states. Empirical studies emphasize the main advantages of currency union membership lies with the elimination of exchange rate volatility to increase savings, relaxation of policies that hinder the free movement of persons and capital to improve trade and tourism, price transparency to intensify trade, and the ability to induce greater Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) to stimulate intra-trade flows (Rose, 2000; Micco et al., 2003; Aristotelous & Fountas, 2009; Rodriguez et al, 2012). The key areas that benefit from currency union membership include production, the financial market, the labour market, tourism, the private sector, the political environment among others (Karlinger, 2002; Martinez et al, 2018; Formaro, 2020). -

African Dialects

African Dialects • Adangme (Ghana ) • Afrikaans (Southern Africa ) • Akan: Asante (Ashanti) dialect (Ghana ) • Akan: Fante dialect (Ghana ) • Akan: Twi (Akwapem) dialect (Ghana ) • Amharic (Amarigna; Amarinya) (Ethiopia ) • Awing (Cameroon ) • Bakuba (Busoong, Kuba, Bushong) (Congo ) • Bambara (Mali; Senegal; Burkina ) • Bamoun (Cameroons ) • Bargu (Bariba) (Benin; Nigeria; Togo ) • Bassa (Gbasa) (Liberia ) • ici-Bemba (Wemba) (Congo; Zambia ) • Berba (Benin ) • Bihari: Mauritian Bhojpuri dialect - Latin Script (Mauritius ) • Bobo (Bwamou) (Burkina ) • Bulu (Boulou) (Cameroons ) • Chirpon-Lete-Anum (Cherepong; Guan) (Ghana ) • Ciokwe (Chokwe) (Angola; Congo ) • Creole, Indian Ocean: Mauritian dialect (Mauritius ) • Creole, Indian Ocean: Seychelles dialect (Kreol) (Seychelles ) • Dagbani (Dagbane; Dagomba) (Ghana; Togo ) • Diola (Jola) (Upper West Africa ) • Diola (Jola): Fogny (Jóola Fóoñi) dialect (The Gambia; Guinea; Senegal ) • Duala (Douala) (Cameroons ) • Dyula (Jula) (Burkina ) • Efik (Nigeria ) • Ekoi: Ejagham dialect (Cameroons; Nigeria ) • Ewe (Benin; Ghana; Togo ) • Ewe: Ge (Mina) dialect (Benin; Togo ) • Ewe: Watyi (Ouatchi, Waci) dialect (Benin; Togo ) • Ewondo (Cameroons ) • Fang (Equitorial Guinea ) • Fõ (Fon; Dahoméen) (Benin ) • Frafra (Ghana ) • Ful (Fula; Fulani; Fulfulde; Peul; Toucouleur) (West Africa ) • Ful: Torado dialect (Senegal ) • Gã: Accra dialect (Ghana; Togo ) • Gambai (Ngambai; Ngambaye) (Chad ) • olu-Ganda (Luganda) (Uganda ) • Gbaya (Baya) (Central African Republic; Cameroons; Congo ) • Gben (Ben) (Togo -

Legal Instruments – Adopted in Malabo – July 2014

AFRICAN UNION UNION AFRICAINE UNIÃO AFRICANA Addis Ababa, ETHIOPIA P. O. Box 3243 Telephone: 517 700 Fax: 5130 36 website: www. www.au.int EXECUTIVE COUNCIL Twenty-Fifth Ordinary Session 20 - 24 June 2014 Malabo, EQUATORIAL GUINEA EX.CL/846(XXV) Original: English THE REPORT, THE DRAFT LEGAL INSTRUMENTS AND RECOMMENDATIONS OF THE SPECIALIZED TECHNICAL COMMITTEE ON JUSTICE AND LEGAL AFFAIRS EX.CL/846(XXV) Page 1 THE REPORT, THE DRAFT LEGAL INSTRUMENTS AND RECOMMENDATIONS OF THE SPECIALIZED TECHNICAL COMMITTEE ON JUSTICE AND LEGAL AFFAIRS 1. The First Meeting of the Specialised Technical Committee (STC) on Justice and Legal Affairs (former Conference of Ministers of Justice/Attorneys or Keepers of the Seal from Member States but now including Ministers responsible for issues such as human rights, constitutionalism and rule of law) was held in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, from 6 to 14 May 2014 (Experts) and 15-16 May 2014 (Ministers). 2. The First Ministerial Session of the STC was attended by thirty eight (38) Member States, two (2) AU Organs and one (1) Regional Economic Community (REC). 3. The purpose of the meeting was to finalize seven (7) Draft Legal Instruments prior to their submission to and adoption by the Policy Organs. 4. Consequently, the STC considered the following Draft Legal Instruments: a) Draft African Union Convention on Cross-border Cooperation (Niamey Convention); b) Draft African Charter on the Values and Principles of Decentralization, Local Governance and Local Development; c) Draft Protocol and Statute on the Establishment of the African Monetary Fund; d) Draft African Union Convention on Cyber-Security and Protection of Personal Data; e) Draft Protocol on Amendments to the Protocol on the Statute of the African Court of Justice and Human Rights; f) Draft Protocol to the Constitutive Act of the African Union on the Pan- African Parliament; and g) Draft Rules of Procedure of the Specialized Technical Committee (STC) on Justice and Legal Affairs. -

THE AFRICAN UNION: Forward March Or About Face-Turn?

THE AFRICAN UNION: Forward March or About Face-Turn? Amadu Sesay Claude Ake Memorial Papers No. 3 Department of Peace and Conflict Research Uppsala University & Nordic Africa Institute Uppsala 1 © 2008 Amadu Sesay, DPCR, NAI ISSN 1654-7489 ISBN 978-91-506-1990-4 Printed in Sweden by Universitetstryckeriet, Uppsala 2008 Distributed by the Department of Peace and Conflict Research (DPCR), Uppsala University & the Nordic Africa Institute (NAI), Uppsala Phone (DPCR) +46 18 471 76 52; (NAI) +46 18 56 22 00 Fax (DPCR) +46 18 69 51 02; (NAI) +46 18 56 22 90 E-mail (DPCR) [email protected]; (NAI) [email protected] www.pcr.uu.se; www.nai.uu.se 2 The Claude Ake Visiting Chair A Claude Ake Visiting Chair was set up in 2003 at the Department of Peace and Conflict Research (DPCR), Uppsala University, in collaboration with the Nordic Africa Institute (NAI), also in Uppsala. Funding was provided from the Swedish Government, through the Swedish Ministry for Foreign Affairs. The Chair was established to honour the memory of Professor Claude Ake, distinguished scholar, philosopher, teacher, activist and human- ist, tragically killed in a plane crash near Lagos, Nigeria, in 1996. The holders of the Claude Ake Visiting Chair give, at the end of their stay in Uppsala, a public lecture, entitled the ‘Claude Ake Memorial Lecture.’ While the title, thematic and content of the lecture is up to the holder, the assumption is that the topic of the lecture shall, in a general sense, relate the work of the holder to the work of Claude Ake, for example in terms of themes or issues covered, or in terms of theoretical or normative points of departure. -

Ecowas Common Currency: How Prepared Are Its Members?

ECOWAS COMMON CURRENCY: HOW PREPARED ARE ITS MEMBERS? Sagiru Mati Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences of the Near East University (Cyprus) Irfan Civcir Faculty of Political Science of the Ankara University (Turkey) Corresponding author: [email protected] Hüseyin Ozdeser Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences of the Near East University (Cyprus) Received October 13, 2018. Accepted February 7, 2019. ABSTRACT This study operationalizes the Optimum Currency Area (oca) to investigate the preparedness of Economic Community of West African States (ecowas) members to form a Monetary Union (mu). Inflation and output models are estimated, with the sample 1988:01 to 2017:12 for the former and 1967 to 2016 for the latter. Analyses of ecowas convergence criteria, impulse responses, variance de- compositions and correlations of shocks of these two models, reveal that the shocks across the ecowas members are asymmetric. The conclusion is that ecowas members as a whole are not well-prepared and therefore a full-fledged pan-ecowas mu is not advisable. It is also found that members of the European Monetary Union (emu) tend to be a better fit for oca than the ecowas members. The study recommends various courses of action such as fostering coordination among Central Banks of ecowas members, and providing a fund to serve as an incentive for countries that may incur cost rather than benefit if the single currency is created. Key words: Optimal Currency Area, ecowas, emu, structural var, Blanchard-Quah decomposition. jel Classification: C13, E31, E52, E58, F33, F42. http://dx.doi.org/10.22201/fe.01851667p.2019.308.69625 © 2019 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Facultad de Economía.