Ray Schalk: a Baseball Biography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![1914-01-05 [P ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5784/1914-01-05-p-135784.webp)

1914-01-05 [P ]

'* *'V";t'ivv -»r p - »«^ rtr< " <a <* „ *,,, tJI '' ,v * < t lllSIlISi 'v 1 ' & * * . o * * . - *• , - >*-'. V s. 5 1 ....'.:?v>;^ »5v ' ^ y.h--- y< IE EIGHT. • A..•'•:•' '.,4 .•*, ,"*,.- -vs'. * f« THE EVENING TIMES. GRAND FORKS, N. D. MONDAY, JANUARY 5, IMS. I*' Winter News and Gossips^Wor ort ML HtSOT "™* and Knobs—-At Last Hank Sees a Chance to Get Some Easy Money By Farren •ee.BUT this is rTHCRE'S 6EEM V<HV ^»U rmtTu.t * RftTTON RiDttf, toy A V4RE.C*.! HAT HEM) Mt,H<o8V, H6, Mts. I M ALMOiT TRAIN , fc MKH CMi'T HAVE. TWG. SURE THEY . t *•$<> ,v, HAVt A SLEEP VlflTHCUT TW5TWM OFFICIALS OF- I DON'T P«SS»TtV£ n ^ ? N H lL BE MIEN HAVENT G36T — WHY? BEIN' WWEO BV WE. MtAM VJR£CK?I BOWPEP TOE R0«> «*• THNK. s Mmpin AND — I k»TV A the mict 66-/ HERE NCT? • • • if rtant Meeting of Na- eoT went w ? ft*RiADY Inal Commission and IN&PECIIOlt |aternity Committee ERS' DEMANDS iRE TO BE HEARD _ i lent Fultz of the Fed- j £ lion is Confident They Will Succeed. ! mia.ti. .Inn. -Tin- .1 rriwd storduj i'f I'resident 1 >;in .I'din- the American league, Neerr- I111 Heydler of the National and r.nrney I > r< • >•1"i 1:-;s. prer-d- JESS WILLARD THINKS HE'LL SOON BE HEAVYWEIGHT CHAMP tlio I'ii tsiiurgli club «'f the |al league. is forerunner cling ill" tin' lint iimal baseball Ission tii'i'r today tint bids fair »o baseball history. MATTER OF os the initial appeaianee 011 TOWARD FEDERALS tional commission of John K. -

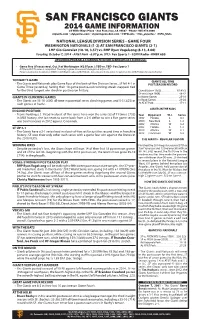

NLDS Notes GM 4.Indd

SAN FRANCISCO GIANTS 2014 GAME INFORMATION 24 Willie Mays Plaza •San Francisco, CA 94107 •Phone: 415-972-2000 sfgiants.com •sfgigantes.com •sfgiantspressbox.com •@SFGiants •@los_gigantes• @SFG_Stats NATIONAL LEAGUE DIVISION SERIES - GAME FOUR WASHINGTON NATIONALS (1-2) AT SAN FRANCISCO GIANTS (2-1) LHP Gio Gonzalez (10-10, 3.57) vs. RHP Ryan Vogelsong (8-13, 4.00) Tuesday, October 7, 2014 • AT&T Park • 6:07 p.m. (PT) • Fox Sports 1 • ESPN Radio • KNBR 680 UPCOMING PROBABLE STARTING PITCHERS & BROADCAST SCHEDULE: • Game Five (if necessary), Oct. 9 at Washington (#2:07p.m.): TBD vs. TBD- Fox Sports 1 # If the LAD/STL series is completed, Thursday's game time would change to 5:37p.m. PT Please note all games broadcast on KNBR 680 AM (English radio) and ESPN Radio. All postseason home games broadcast on 860 AM ESPN Deportes (Spanish radio). TONIGHT'S GAME GIANTS ALL-TIME • The Giants and Nationals play Game Four of this best-of- ve Division Series...SF fell 4-1 in POSTSEASON RECORD Game Three yesterday, having their 10-game postseason winning streak snapped, tied for the third-longest win streak in postseason history. Overall (since 1900) . 87-83-2 SF-era (since 1958) . .48-42 GIANTS IN CLINCHING GAMES In Home Games . .25-18 • The Giants are 15-10 (.600) all-time in potential series clinching games and 5-3 (.625) in In Road Games. .23-24 such games at home. At AT&T Park . .17-11 GIANTS IN THE NLDS IN GOOD POSITION • Teams holding a 2-1 lead in a best-of- ve series have won the series 52 of 71 times (.732) Year Opponent W-L Series in MLB history...the last team to come back from a 2-0 de cit to win a ve game series 1997 Florida L 0-3 was San Francisco in 2012 against Cincinnati. -

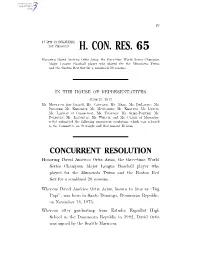

H. Con. Res. 65

IV 115TH CONGRESS 1ST SESSION H. CON. RES. 65 Honoring David Ame´rico Ortiz Arias, the three-time World Series Champion Major League Baseball player who played for the Minnesota Twins and the Boston Red Sox for a combined 20 seasons. IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES JUNE 23, 2017 Mr. MOULTON (for himself, Mr. CAPUANO, Mr. NEAL, Ms. DELAURO, Ms. PINGREE, Mr. KENNEDY, Mr. MCGOVERN, Mr. KEATING, Mr. LYNCH, Mr. LARSON of Connecticut, Ms. TSONGAS, Ms. SHEA-PORTER, Mr. POLIQUIN, Mr. LANGEVIN, Mr. WELCH, and Ms. CLARK of Massachu- setts) submitted the following concurrent resolution; which was referred to the Committee on Oversight and Government Reform CONCURRENT RESOLUTION Honoring David Ame´rico Ortiz Arias, the three-time World Series Champion Major League Baseball player who played for the Minnesota Twins and the Boston Red Sox for a combined 20 seasons. Whereas David Ame´rico Ortiz Arias, known to fans as ‘‘Big Papi’’, was born in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, on November 18, 1975; Whereas after graduating from Estudia Espaillat High School in the Dominican Republic in 1992, David Ortiz was signed by the Seattle Mariners; VerDate Sep 11 2014 02:12 Jun 24, 2017 Jkt 069200 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6652 Sfmt 6300 E:\BILLS\HC65.IH HC65 SSpencer on DSKBBV9HB2PROD with BILLS 2 Whereas, on September 2, 1997, David Ortiz made his Major League Baseball debut for the Minnesota Twins at age 21; Whereas, on January 22, 2003, David Ortiz signed a free- agent contract with the Boston Red Sox; Whereas David Ortiz has created numerous iconic moments -

Base Ball and Trap Shooting

MBfc Tag flMffll ~y^siMf " " f" BASE BALL AND TRAP SHOOTING VOL. 64. NO. 7 PHILADELPHIA, OCTOBER 17, 1914 PRICE 5 CENTS National League Pennant Winners Triumph Over Athletics in Four Straight Games, Setting a New Record for the Series Former Title Holders Are Outclassed, Rudolph and James Each Win Two Games Playing the most sensational and surprising that single tally was the result of a "high l>ase ball ever seen in a World©s Series, the throw to the plate by Collins on a double Boston National League Club won the pre steal. mier base ball honors from the Athletics, Hero of the World©s Series THE DIFFERENCE IN PITCHING champions of the American League in four made the Athletics appear to disadvantage, ©aa straight games, the series closing on October light hitting always does with any team, while 13, in Boston. Never before had any club cap Ithe winning start secured by the Braves tured the World©s Championship in the short made them appear perhaps stronger than the space of four games, and it is doubtful Athletics, on this occasion at least. At any whether in any previous series a former rate they played pretty much the game that World©s Champion team fell away so badly won their league pennant. They fielded with as did the American League title-holders. precision and speed, ran bases with reckless Rudolph and James were the two Boston abandon, and showed courage and aggressive Ditchers who annexed the victories, each tri ness from the moment they gained the lead. -

The Meadoword, June 2017

June 2017 Volume 35, Number 06 The To FREE Meadoword MeaThe doword PUBLISHED BY THE MEADOWS COMMUNITY ASSOCIATION TO PROVIDE INFORMATION AND EDUCATION FOR MEADOWS RESIDENTS MANASOTA, FL MANASOTA, U.S. POSTAGE PRESORTED STANDARD PERMIT 61 PAID PDF done -CC 2 The Meadoword • June 2017 MCA BOARD OF DIRECTORS Notes From the Claire Coyle, President Marilyn Maleckas, Vice President Joe Miller, Treasurer Malcolm Hay, Secretary President’s Desk Bob Clark Claire Coyle—MCA President Bruce Ferretti Phil Hughes Jan Lazar The Renaissance of property values will increase by more distributed about a year ago. Leaders Dr. Bart Levenson The Meadows than six percent. And, that is only the of the community built on this data in COMMITTEES beginning. two meetings of association presidents Assembly of Property Owners is about to begin Real estate experts tell us that new and assembly members. The result is a Pam Campbell, Chair plan that calls for upgrading the overall Claire Coyle, Liaison construction usually causes the value The recent announcement that The look of our community. Communications of properties in the surrounding areas Claire Coyle, Chair Meadows Country Club has signed an to increase Everything ties together to make Community Involvement agreement with a developer to build this time an incredibly exciting one Marilyn Maleckas, Chair up to 180 new units on the property New construction also stimulates to be a member of The Meadows Finance and Budget now owned by the country club existing homeowners to invest in community. New building will bring Jerry Schwarzkopf, Chair signaled the start of the revitalization upgrading their properties to keep new people and renewed energy. -

Santa Fe New Mexican, 06-07-1913 New Mexican Printing Company

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Santa Fe New Mexican, 1883-1913 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 6-7-1913 Santa Fe New Mexican, 06-07-1913 New Mexican Printing company Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sfnm_news Recommended Citation New Mexican Printing company. "Santa Fe New Mexican, 06-07-1913." (1913). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sfnm_news/3818 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Santa Fe New Mexican, 1883-1913 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 ! SANTA 2LWWJlaWl V W SANTA FE, NEW MEXICO, SATURDAY, JUNE 7, 191J. JVO. 95 WOULD INVOLVE PRESIDlNT D0RMAN THE SQUEALERS. CONFERENCE OF ! SENDS GREETINGS GOVERNORS THE CHAMBER OF COMMERCE HAS A COMPREHENSIVE FOLDER PRIN- WILSON TED SEND TO THE BROTHERHOOD CLOSES OF AMERICAN YEOMEN, CALLING REPUBLICAN SENATORS STILL INS-SIS- T ATTENTION TO SANTA FE S WILL DRAFT ADDRESS TO PUBLIC THAT PRESIDENT IS USING LAND OFFICE COMMISSIONER MORE INFLUENCE FOR TARIFF TALLMAN AND A. A. JONES PRO-- i If the smoker and lunch given by THAN ANYONE ELSE. MISE HELP OF THE the chamber of commerce brought forth nothing else, the issuing of WILSON IS LOBBYING greetings to the supreme conclave of the Brotherhood of American Yeoman, FOR THE PEOPLE Betting forth some of the facts re- PROSPECTORS WILL garding Santa Fe and its remarkable climate was worth accomplishment. BE ENCOURAGED Washington, D. C, June 7. -

The 112Th World Series Chicago Cubs Vs. Cleveland Indians Saturday, October 29, 2016 Game 4 - 7:08 P.M

THE 112TH WORLD SERIES CHICAGO CUBS VS. CLEVELAND INDIANS SATURDAY, OCTOBER 29, 2016 GAME 4 - 7:08 P.M. (CT) FIRST PITCH WRIGLEY FIELD, CHICAGO, ILLINOIS 2016 WORLD SERIES RESULTS GAME (DATE RESULT WINNING PITCHER LOSING PITCHER SAVE ATTENDANCE Gm. 1 - Tues., Oct. 25th CLE 6, CHI 0 Kluber Lester — 38,091 Gm. 2 - Wed., Oct. 26th CHI 5, CLE 1 Arrieta Bauer — 38,172 Gm. 3 - Fri., Oct. 28th CLE 1, CHI 0 Miller Edwards Allen 41,703 2016 WORLD SERIES SCHEDULE GAME DAY/DATE SITE FIRST PITCH TV/RADIO 4 Saturday, October 29th Wrigley Field 8:08 p.m. ET/7:08 p.m. CT FOX/ESPN Radio 5 Sunday, October 30th Wrigley Field 8:15 p.m. ET/7:15 p.m. CT FOX/ESPN Radio Monday, October 31st OFF DAY 6* Tuesday, November 1st Progressive Field 8:08 p.m. ET/7:08 p.m. CT FOX/ESPN Radio 7* Wednesday, November 2nd Progressive Field 8:08 p.m. ET/7:08 p.m. CT FOX/ESPN Radio *If Necessary 2016 WORLD SERIES PROBABLE PITCHERS (Regular Season/Postseason) Game 4 at Chicago: John Lackey (11-8, 3.35/0-0, 5.63) vs. Corey Kluber (18-9, 3.14/3-1, 0.74) Game 5 at Chicago: Jon Lester (19-5, 2.44/2-1, 1.69) vs. Trevor Bauer (12-8, 4.26/0-1, 5.00) SERIES AT 2-1 CUBS AT 1-2 This is the 87th time in World Series history that the Fall Classic has • This is the eighth time that the Cubs trail a best-of-seven stood at 2-1 after three games, and it is the 13th time in the last 17 Postseason series, 2-1. -

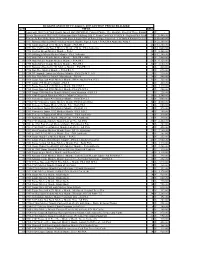

PDF of August 17 Results

HUGGINS AND SCOTT'S August 3, 2017 AUCTION PRICES REALIZED LOT# TITLE BIDS 1 Landmark 1888 New York Giants Joseph Hall IMPERIAL Cabinet Photo - The Absolute Finest of Three Known Examples6 $ [reserve - not met] 2 Newly Discovered 1887 N693 Kalamazoo Bats Pittsburg B.B.C. Team Card PSA VG-EX 4 - Highest PSA Graded &20 One$ 26,400.00of Only Four Known Examples! 3 Extremely Rare Babe Ruth 1939-1943 Signed Sepia Hall of Fame Plaque Postcard - 1 of Only 4 Known! [reserve met]7 $ 60,000.00 4 1951 Bowman Baseball #253 Mickey Mantle Rookie Signed Card – PSA/DNA Authentic Auto 9 57 $ 22,200.00 5 1952 Topps Baseball #311 Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 40 $ 12,300.00 6 1952 Star-Cal Decals Type I Mickey Mantle #70-G - PSA Authentic 33 $ 11,640.00 7 1952 Tip Top Bread Mickey Mantle - PSA 1 28 $ 8,400.00 8 1953-54 Briggs Meats Mickey Mantle - PSA Authentic 24 $ 12,300.00 9 1953 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 (MK) 29 $ 3,480.00 10 1954 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 58 $ 9,120.00 11 1955 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 20 $ 3,600.00 12 1952 Bowman Baseball #101 Mickey Mantle - PSA FR 1.5 6 $ 480.00 13 1954 Dan Dee Mickey Mantle - PSA FR 1.5 15 $ 690.00 14 1954 NY Journal-American Mickey Mantle - PSA EX-MT+ 6.5 19 $ 930.00 15 1958 Yoo-Hoo Mickey Mantle Matchbook - PSA 4 18 $ 840.00 16 1956 Topps Baseball #135 Mickey Mantle (White Back) PSA VG 3 11 $ 360.00 17 1957 Topps #95 Mickey Mantle - PSA 5 6 $ 420.00 18 1958 Topps Baseball #150 Mickey Mantle PSA NM 7 19 $ 1,140.00 19 1968 Topps Baseball #280 Mickey Mantle PSA EX-MT -

UP to Date Sports) Griff Laughs at Claims That Mcbride Has Jumped to Feds

12 THE WASHINGTON TIMES, WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 2, 1913." UP TO date sports) Griff Laughs at Claims That McBride Has Jumped to Feds I YJ-vL- m , . 1m - Lm --w 7 7 JTL? 7 7 LrtY'l 1Af I J sX- iJm-- L T Claim George McBride SCHOOLBOY CELEBRITIES JDUOUIVOO nigfl JDUSKVLUUU VJUITLL WILL MINCE PIE No. 2. A LITTLE OF EVERYTHING Battle Gonzaga Today in First Game fV Will Be With Federal By "BUGS" BAER. Th Stenographers Are Suffering Gene Ochsenreiter Expected to rorrerins Elslane houId be slad tf- -r NET BIG SUM weren t picked to manage the Yanks. League Is Not Believed From Too Much Classy Ma- Be Named Captain of Tech's Yale hotcl -- Jri'C witl accommodate One of the reasons for the belief 1 0,000, tut vou . fc LIIHLiLIIIIIIH!998H&fliLllllflilLHIilllHk: terial for Its Outfit. Eleven Today. couldn't ii, that the Ohio Legislature will Amtrican eleven in there without usir.n a Though Invaders Include Dandy Captain's Name in Griff SHWV-H- f List, create a State boxing illlllllllllllBisllllllllliilllB!9tlillllllllliiilllslllllllllllllsLE& commission at its next session is Says Veteran Has Signed Here for 1915 Old Fox Isn't By BRYAN MORSE. found in the to make the regulars put up a fight War tax on telephone calls is , to positions. calamity, nlrkpra a Capt. Ray Wise, of the Business prosperity of tho Wisconsin sport. retain their - su - " - r m elevens pick Worrying Over Johnson's Case Either. basketball team, is leading his bunch The Milwaukee game has paid Graduation and moving have robbed their teams that way. -

Jimmy Johnston Earns Amateur Golftitle

SPORTS AND FINANCIAL Base Ball, Racing Stocks and Bonds Golf and General Financial News l_ five Jhinttmi fKtaf Part s—lo Pages WASHINGTON, 13. C., SUNDAY MORNING, SEPTEMBER 8, 1929. Griffs Beat Chisox in Opener, 2—l: Jimmy Johnston Earns Amateur Golf Title VICTOR AND VANQUISHED IN NATIONAL AMATEUR GOLF TOURNAMENT ¦¦ '¦ * mm i 1 11—— 1 I ¦¦l. mm MARBERRY LICKS THOMAS 1 i PRIDE OF ST. PAUL WINS IN FLASHY MOUND TUSSLE | ....... OYER DR. WILLING, 4 AND 3 i '<l \ j u/ Fred Yields Hut Six Hits and Holds Foe Seoreless JT Makes Strong Finish After Ragged Play in Morn- Until Ninth—Nats Get Seven Safeties—Earn ing to Take Measure of Portland Opponent. W '' ' / T Executes - of One Run, Berg Hands Them Another. /. / 4- jr""'"" 1 \ \ Wonder Shot Out Ocean. / 5 - \ \ •' * 11 f _jl"nil" >.< •*, liL / / A \ BY GRAXTLAND RICE. BY JOHN B. KELLER. Thomas on MONTE, Calif., September 7.—The green, soft fairway of MARBERRY was just a trifle stronger than A1 Pebble Beach the a new amateur as White Sex A \ caught footfall of champion the pitching slab yesterday the Nationals and f this afternoon. His name is Harrison ( series of the year ( Jimmy) Johnston, the clashed in the opening tilt of their wind-up PBHKm DELpride of St. Paul, who after a game, up-hill battle all through charges scored a 2-to-l victory that FREDand as a result Johnson’s \ morning fought his way into victory the grim, hard- back of the fifth-place Tigers, the crowd wtik the round, over left them but half a game fighting Doc Willing of Portland, Ore., by the margin of 4 and 3. -

National League News in Short Metre No Longer a Joke

RAP ran PHILADELPHIA, JANUARY 11, 1913 CHARLES L. HERZOG Third Baseman of the New York National League Club SPORTING LIFE JANUARY n, 1913 Ibe Official Directory of National Agreement Leagues GIVING FOR READY KEFEBENCE ALL LEAGUES. CLUBS, AND MANAGERS, UNDER THE NATIONAL AGREEMENT, WITH CLASSIFICATION i WESTERN LEAGUE. PACIFIC COAST LEAGUE. UNION ASSOCIATION. NATIONAL ASSOCIATION (CLASS A.) (CLASS A A.) (CLASS D.) OF PROFESSIONAL BASE BALL . President ALLAN T. BAUM, Season ended September 8, 1912. CREATED BY THE NATIONAL President NORRIS O©NEILL, 370 Valencia St., San Francisco, Cal. (Salary limit, $1200.) AGREEMENT FOR THE GOVERN LEAGUES. Shields Ave. and 35th St., Chicago, 1913 season April 1-October 26. rj.REAT FALLS CLUB, G. F., Mont. MENT OR PROFESSIONAL BASE Ills. CLUB MEMBERS SAN FRANCIS ^-* Dan Tracy, President. President MICHAEL H. SEXTON, Season ended September 29, 1912. CO, Cal., Frank M. Ish, President; Geo. M. Reed, Manager. BALL. William Reidy, Manager. OAKLAND, ALT LAKE CLUB, S. L. City, Utah. Rock Island, Ills. (Salary limit, $3600.) Members: August Herrmann, of Frank W. Leavitt, President; Carl S D. G. Cooley, President. Secretary J. H. FARRELL, Box 214, "DENVER CLUB, Denver, Colo. Mitze, Manager. LOS ANGELES A. C. Weaver, Manager. Cincinnati; Ban B. Johnson, of Chi Auburn, N. Y. J-© James McGill, President. W. H. Berry, President; F. E. Dlllon, r>UTTE CLUB, Butte, Mont. cago; Thomas J. Lynch, of New York. Jack Hendricks, Manager.. Manager. PORTLAND, Ore., W. W. *-* Edward F. Murphy, President. T. JOSEPH CLUB, St. Joseph, Mo. McCredie, President; W. H. McCredie, Jesse Stovall, Manager. BOARD OF ARBITRATION: S John Holland, President. -

The Painted Angel” They Are Admired for Beauty Alone, Then Progress Demands That They Wide

: 4 . • f ’ THE PLYMOUTH MAIL THE HOME NEWSPAPER PLYMOUTH, MICHIGAN, FRIDAY, AUGUST 22,-1930. TWELVE PAGES* FIVE CENTS $i.5O per year, VOL. 42 NO. 40 CHENOT TALKS TO. Every member of the Plymouth Kiwanis Members Chamber of Commerce and others PUBLIC SCHOOLS LOCAL ROTARIANS concerned with affairs of civic in Hear District terest should read S e c r e t a ry G. OF C. MEMBERS URGED TO Moore’s report to the Board of Di rectors at their meeting* last Mon Music Chairman day, August 18th. OPEN TUESDAY, The Kiwanis Club had a very enjoy SUPPORT LARRY JOHNSON able meeting Tuesday. The program Will Dedicate was in charge of Rev. Oscar Seitz. Though for nearly two months past Walter Fenton. Kiwanis District music EX-LEGISUATOR JOHNSON HAS Plymouth and vicinity have not had a chairman of M.t. Clemens, was present Unaliyi Group At FINE RECORD. SEPTEMBER 2ND County Airport real hard rain, and the effects of the and gave an interesting talk and led prolonged drouth are everywhere ap the singing. Miss I’ansy Bell and Camp Wathana September 4 parent. the Village of Plymouth has Fred Shock of Mr. Clemens, were the THIS SATURDAY, AUGUST 23RD, Vacation period, which Is rapidly been fortunate in having had a abund accompanists. drawing to a close, has acted as a tune ance of water available for all do Nine girls of the Unaliyi Campfire YOl R LAST CHANCE TO in which the Board of Education could Last Monday the Wayne County mestic and industrial requirements, group of Rosedale Gardens are spend REGISTER.