Restorative Justice Cover-02

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

October 12-18 Videofest.Org Video Association of Dallas Make Films That Matter

ANGELIKA FILM CENTER OCTOBER 12-18 VIDEOFEST.ORG VIDEO ASSOCIATION OF DALLAS MAKE FILMS THAT MATTER UNIVERSITY OF The Department of Art and TEXAS ARLINGTON Art History at UTA has an ART+ART HISTORY excellent reputation for FILM/VIDEO PROGRAM grooming young filmmakers, preparing WWW.UTA.EDU/ART 817-272-2891 them for the creative challenges and emotional rigors of the motion picture industry. Call our advising sta to find out how you can train to be a vital part of the film industry. Art Art History Department 2 CONTENTS 2 BROUGHT TO YOU BY 3 2015 BOARD OF DIRECTORS 4 SPONSORS & CONTRIBUTORS 8 WELCOME BY BART WEISS 10 ABOUT OUR JURORS 14 TEXAS SHOW JURORS 16 KOVACS AWARD 18 HONOREES 26 SCREENINGS 52 SCHEDULE 1 BROUGHT TO YOU BY BARTON WEISS YA’KE SMITH Artistic Director Festival Bumpers RAQUEL CHAPA MARK WICKERSHAM Managing Director KARL SCHAEFFER Transportation BOXOFFICE: PREKINDLE SELIG POLYSCOPE COMPANY CAMERON NELSON Videography Technical Supervisor REDMAN I AM CHRISTIAN VASQUEZ Trophies DAVID GRANDBERRY Technical Assistant MATTHIEU CARTAL DAKOTA FORD MARISSA ALANIS MATTHEW GEISE MARGARITA BIRNBAUM VIVIAN GRAY AMY MARTIN Outreach MIKE MILLER YUMA MORRIS KELLY J KITCHENS ELEONORA SOLDATI Interns RONI HUMMEL Media Relations/Entertainment Publicity BETH JASPER ALVIN HYSONG DANA TURNER MARSHALL PITMAN Program Editor WES SUTTON Programmers TAMITHA CURIEL Newsletter Editor RON SIMON Curator of Television Pasily Center CYNTHIA CHAPA Program Content ED BARK Critic Uncle Barkey SULLIVANPERKINS MICHAEL CAIN Graphic Design Filmmaker, former head of AFI Dallas Festival DESIGN TEXAS - UT ARLINGTON JOSH MILLS Program Book Design It’s Alive! Media & Management DEV SHAPIRO Kovacs Committee DARREN DITTRICH Webpage 2 BOARD OF DIRECTORS JEFFREY A. -

Travel Report JO March09.Doc – Julia Overton March 2009 2 Screen Australia – March 2009

T R IDFA & World Congress of Science and Factual Producers 2008, O with additional London meetings P Julia Overton, Investment and Development Manager – Documentary The objectives for attending IDFA and World Congress of Science and E Factual Producers were many. To have face-to-face meetings with potential co-producing partners, broadcasters, commissioning editors, sales agents and distributors who could work with Australian companies to enable R developed projects to be produced and finished projects to find a place in the market. To support the Australian filmmakers attending the events – in the case of IDFA it was those who had projects screening in the festival or who were pitching projects in the Forum or private meetings. To observe which L documentaries were finding an audience, and in what form. And to establish new contacts, particularly in the area of science producing, where the cost of production is such that numerous co-production partners are usually E essential. Attending the two events back-to-back was an interesting conjunction of market/festival. It is best expressed via two conversations I had on my first V day at each event. When asking a filmmaker at IDFA why they were there I was told it was with a film which was a ‘post-Brechtian deconstruction of the Israeli Palestinian conflict’ and on asking the same question at World A Congress the response was ‘to sell 26 hours on killer reptiles’. It gave a wonderful insight to the diversity of the world that is documentary. London R Before the festivals, time was spent in London having meetings with some of those with whom Screen Australia deals on a regular basis. -

Stranger Than Fiction

stf_2007 23/08/2007 11:30 Page i Stranger Than Fiction Documentary Film Festival and Market 13th-16th September 2007 stf_2007 23/08/2007 11:30 Page ii Introduction It’s my great pleasure to welcome This year’s opening feature The of the films screening, as well as you to this year’s Stranger Than Undertaking stands out as one of the contributions from David Norris, Fiction Festival. This is the sixth most beautiful films to come out of Louis de Paor, Stephen Rea and year of the event, and the first Ireland in many years. Richard Boyd Barrett. without the indomitable Gráinne The feature-length documentary This is perhaps a golden age of Humphreys at the helm. With continues to thrive on the inter- documentary film, and for the four Gráinne’s departure, Irish Film national scene, and I have selected 14 days of Stranger Than Fiction, I’d Institute Director Mark Mulqueen films which I hope you will at turns encourage you to come to the IFI to decided to approach this year’s find provocative, entertaining, heart- meet the filmmakers, to partake in festival in a different way, opting to breaking, hilarious; and always, I the market, to engage in the discus- bring an independent film-maker on hope, deeply affecting. Truth is indeed sions, and to see the finest of docu- board as Festival Director. stranger that fiction, and documen- mentary films from Ireland as well as As a documentary-maker used to taries tap into humanity in all its from throughout the world. submitting films to such festivals, I vagaries in ways that drama can’t; was delighted to be asked to put witness the delightful and witty James Kelly together this event. -

Appendix A: Non-Executive Directors of Channel 4 1981–92

Appendix A: Non-Executive Directors of Channel 4 1981–92 The Rt. Hon. Edmund Dell (Chairman 1981–87) Sir Richard Attenborough (Deputy Chairman 1981–86) (Director 1987) (Chairman 1988–91) George Russell (Deputy Chairman 1 Jan 1987–88) Sir Brian Bailey (1 July 1985–89) (Deputy Chairman 1990) Sir Michael Bishop CBE (Deputy Chairman 1991) (Chairman 1992–) David Plowright (Deputy Chairman 1992–) Lord Blake (1 Sept 1983–87) William Brown (1981–85) Carmen Callil (1 July 1985–90) Jennifer d’Abo (1 April 1986–87) Richard Dunn (1 Jan 1989–90) Greg Dyke (11 April 1988–90) Paul Fox (1 July 1985–87) James Gatward (1 July 1984–89) John Gau (1 July 1984–88) Roger Graef (1981–85) Bert Hardy (1992–) Dr Glyn Tegai Hughes (1983–86) Eleri Wynne Jones (22 Jan 1987–90) Anne Lapping (1 Jan 1989–) Mary McAleese (1992–) David McCall (1981–85) John McGrath (1990–) The Hon. Mrs Sara Morrison (1983–85) Sir David Nicholas CBE (1992–) Anthony Pragnell (1 July 1983–88) Usha Prashar (1991–) Peter Rogers (1982–91) Michael Scott (1 July 1984–87) Anthony Smith (1981–84) Anne Sofer (1981–84) Brian Tesler (1981–85) Professor David Vines (1 Jan 1987–91) Joy Whitby (1981–84) 435 Appendix B: Channel 4 Major Programme Awards 1983–92 British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) 1983: The Snowman – Best Children’s Programme – Drama 1984: Another Audience With Dame Edna – Best Light Entertainment 1987: Channel 4 News – Best News or Outside Broadcast Coverage 1987: The Lowest of the Low – Special Award for Foreign Documentary 1987: Network 7 – Special Award for Originality -

Annual Report 2007

ROYAL TELEVISION SOCIETY ANNUAL REPORT 2007 AGM 28 May 2008 at 6:00pm at the RTS, Kildare House, 3 Dorset Rise, London EC4Y 8EN Patrons Pepper Post Production Principal Patrons S4C SMG BBC Sony Business Europe BSkyB Spectrum Strategy Consultants Channel 4 Television UKTV ITV RTS Patrons International Patrons APTN ABN Amro Autocue Accenture Avid Technology Europe Bank of Ireland Corporate Banking Bloomberg Discovery Communications Europe Canon Microsoft Channel Television NBC Universal DTG High Definition Forum RTL Group Granada Television Time Warner Hat Trick Productions Viacom HIT Entertainment Walt Disney Company Ikegami Electronics UK IMS ITV Anglia Major Patrons ITV London ITV Meridian ITV Tyne Tees Arqiva ITV West Ascent Media Networks ITV Yorkshire BT Vision Cable & Wireless Omneon Video Networks Deloitte Panasonic Broadcast Europe DLA Piper PricewaterhouseCoopers Endemol UK Quantel Enders Analysis Radio Telefís Éireann Five Reuters Television FremantleMedia SMG Grampian Television GMTV SMG Scottish Television Guardian Media Group SSVC IMG Media Tektronix (UK) ITN Teletext KPMG Television Systems MCPS-PRS Alliance Ulster Television Millbank Studios University College, Falmouth OC&C Strategy Consultants University of Teesside Ofcom Vinten Broadcast 2 R O YA L T E L E V I S I O N S O C I E T Y REPORT 2007 Contents Patrons 2 Notice of AGM 2008 4 Form of proxy 5 Advisory Council election manifestos 6 Minutes of AGM 2007 7 Board of Trustees report to members 11 National events 2007 25 Centres report 2007 26 Who’s who at the RTS 28 Auditors’ report 30 Financial statements 31 Notes to the financial statements 34 Trustees’ and Directors’ reports 41 Picture credits 47 R O YA L T E L E V I S I O N S O C I E T Y REPORT 2007 3 Notice of AGM 2008 The 79th Annual General Meeting of the Royal Television Agenda Society will be held on Wednesday 28 May 2007 at: 1 To approve the minutes of the previous Annual General Kildare House Meeting held on 23 May 2007. -

MONTY PYTHON at 50 , a Month-Long Season Celebra

Tuesday 16 July 2019, London. The BFI today announces full details of IT’S… MONTY PYTHON AT 50, a month-long season celebrating Monty Python – their roots, influences and subsequent work both as a group, and as individuals. The season, which takes place from 1 September – 1 October at BFI Southbank, forms part of the 50th anniversary celebrations of the beloved comedy group, whose seminal series Monty Python’s Flying Circus first aired on 5th October 1969. The season will include all the Monty Python feature films; oddities and unseen curios from the depths of the BFI National Archive and from Michael Palin’s personal collection of super 8mm films; back-to-back screenings of the entire series of Monty Python’s Flying Circus in a unique big-screen outing; and screenings of post-Python TV (Fawlty Towers, Out of the Trees, Ripping Yarns) and films (Jabberwocky, A Fish Called Wanda, Time Bandits, Wind in the Willows and more). There will also be rare screenings of pre-Python shows At Last the 1948 Show and Do Not Adjust Your Set, both of which will be released on BFI DVD on Monday 16 September, and a free exhibition of Python-related material from the BFI National Archive and The Monty Python Archive, and a Python takeover in the BFI Shop. Reflecting on the legacy and approaching celebrations, the Pythons commented: “Python has survived because we live in an increasingly Pythonesque world. Extreme silliness seems more relevant now than it ever was.” IT’S… MONTY PYTHON AT 50 programmers Justin Johnson and Dick Fiddy said: “We are delighted to share what is undoubtedly one of the most absurd seasons ever presented by the BFI, but even more delighted that it has been put together with help from the Pythons themselves and marked with their golden stamp of silliness. -

Channel 4 and British Film: an Assessment Of

Channel 4 and British Film: An Assessment of Industrial and Cultural Impact, 1982-1998 Laura Mayne This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Portsmouth. September 2014 i Abstract This thesis is an historical investigation of Channel 4’s influence on the British film industry and on British film culture between 1982 and 1998. Combining archival research with interview testimony and secondary literature, this thesis presents the history of a broadcaster’s involvement in British film production, while also examining the cultural and industrial impact of this involvement over time. This study of the interdependence of film and television will aim to bring together aspects of what have hitherto been separate disciplinary fields, and as such will make an important contribution to film and television studies. In order to better understand this interdependence, this thesis will offer some original ideas about the relationship between film and television, examining the ways in which Channel 4’s funding methods led to new production practices. Aside from the important part the Channel played in funding (predominantly low-budget) films during periods when the industry was in decline and film finance was scarce, this partnership had profound effects on British cinema in the 1980s and 1990s. In exploring these effects, this thesis will look at the ways in which the film funding practices of the Channel changed the landscape of the film industry, offered opportunities to emerging new talent, altered perceptions of British film culture at home and abroad, fostered innovative aesthetic practices and brought new images of Britain to cinema and television screens. -

Appendix Screenings and Additional Resources

Appendix Screenings and Additional Resources The analyses of various films and television programmes undertaken in this book are intended to function ‘interactively’ with screenings of the films and programmes. To this end, a complete list of works to accompany each chapter is provided below. Certain of these works are available from national and international distribution companies. Specific locations in the United States, the United Kingdom and Australia for each of the listed works are, nevertheless, provided below. The entries include running time and format (16 mm, VHS, or DVD) for each work. (Please note: In certain countries films require copyright clearance for public screening.) Also included below are further or additional screenings of works not analysed or referred to in each chapter. This information is supplemented by suggested further reading. 1 ‘Believe me, I’m of the world’: documentary representation Further reading Corner, J. ‘Civic visions: forms of documentary’ in J. Corner, Television Form and Public Address (London: Edward Arnold, 1995). Corner, J. ‘Television, documentary and the category of the aesthetic’, Screen, 44, 1 (2003) 92–100. Nichols, B. Blurred Boundaries: Questions of Meaning in Contemporary Culture (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994). Renov, M. ‘Toward a poetics of documentary’ in M. Renov (ed.), Theorizing Documentary (New York: Routledge, 1993). 2 Men with movie cameras: Flaherty and Grierson Nanook of the North, Robert Flaherty, 1922. 55 min. (Alternative title: Nanook of the North: A Story -

Annual Report 2019 Nottingham Trent University with First Class Honours in the Summer of 2019 Why Second Chances Remain the Longford Trust’S First Priority

PO Box 64302 London NW6 9JP [email protected] www.longfordtrust.org @LongfordTrust The Longford Trust Registered Charity No. 1164701 Front cover: Longford Scholar Jacob Dunne celebrates his graduation from Annual Report 2019 Nottingham Trent University with First Class Honours in the summer of 2019 Why Second Chances Remain The Longford Trust’s First Priority The best-laid plans, as they say, often go awry. This year we have been encouraging those who are willing to share the Three weeks before our 2019 Longford Lecture, to stories of some of those challenges in the blog on our website (longfordtrust.(page 16) be given by the Metropolitan Police Commissioner, org/blog/), which we then promote to a wider audience of policy makers Dame Cressida Dick, it couldn’t have been going and campaigners for a better criminal justice system. We include more smoothly. We had a full house and a long an extract from our award-holder Shaun’s account of being released from waiting list for tickets, as well as new caterers in prison and given a tent by his probation officer to live in because there was no Liberty Kitchen, direct from HMP Pentonville. accommodation available for him. Then along came a December general election, Underpinning all our work is the Longford Trust’s lean, efficient office team which meant our speaker was under purdah rules that daily boxes above its weight. You can read inside accounts of their work for senior public servants, and we were back at by Philippa Budgen, Natasha Maw and Jacob Dunne, our scholarship and zero. -

AFI PREVIEW Is Published by the the AFI EU FILM SHOWCASE Auman of the European Union – Delegation of the American Film Institute

*6'0 ! 499) $ (508 4 49+9 / 49 '%&8 &5(3 %( - . %03 8 ($ 0 && 50*,( (%*( %&' #*71 &*1%(" %"#3 *6'0 4+ CONTENTS e e e e OPENING NIGHT! e e e e 2 AFI European Union Film Showcase 9 Holiday Cinema 10 The Secret Policeman’s Film Festival 12 The 20th Washington Jewish Film Festival November 5 – 24 AFI presents the 22nd annual AFI European Union 14 LA DANSE: THE PARIS Film Showcase, a selection of top films from EU member states, including film festival award OPERA BALLET © Memfis Film; photo courtesy of IFC Films winners, box office hits and US premieres. MAMMOTH About AFI AFI thanks the cultural counselors of the EU MAMMOTH [Mammut] member states and the European Commission * THURS, NOV 5, 7:00 *; Sun, Nov 8, 5:00 Delegation in Washington, DC, for their kind Swedish writer/director Lukas Moodysson’s first foray into English-language 15 Calendar assistance and continued support of the AFI filmmaking is a film for and about the global marketplace, and the connections European Union Film Showcase. and separations it imposes on families. Gael García Bernal and Michelle Williams star as a Manhattan couple whose domestic drama has repercussions 16 Special Engagements Special thanks to Ambassador Jonas Hafström, stretching from New York to the Philippines to Thailand, and back again. Cultural Counselor Mats Widbom, and the staff DIR/SCR Lukas Moodysson; PROD Lars Jönsson. Sweden/Denmark/ of the Embassy of Sweden for their leadership Germany, 2009, color, 125 min. In English, Tagalog and Thai with English subtitles. NOT RATED S V LOOK FOR THE and invaluable support as the current holders of AFI Member passes accepted for the EU Presidency. -

The Educational Backgrounds of Leading Journalists

The Educational Backgrounds of Leading Journalists June 2006 NOT FOR PUBLICATION BEFORE 00.01 HOURS THURSDAY JUNE 15TH 2006 1 Foreword by Sir Peter Lampl In a number of recent studies the Sutton Trust has highlighted the predominance of those from private schools in the country’s leading and high profile professions1. In law, we found that almost 70% of barristers in the top chambers had attended fee-paying schools, and, more worryingly, that the young partners in so called ‘magic circle’ law firms were now more likely than their equivalents of 20 years ago to have been independently-educated. In politics, we showed that one third of MPs had attended independent schools, and this rose to 42% among those holding most power in the main political parties. Now, with this study, we have found that leading news and current affairs journalists – those figures who are so central in shaping public opinion and national debate – are more likely than not to have been to independent schools which educate just 7% of the population. Of the top 100 journalists in 2006, 54% were independently educated an increase from 49% in 1986. Not only does this say something about the state of our education system, but it also raises questions about the nature of the media’s relationship with society: is it healthy that those who are most influential in determining and interpreting the news agenda have educational backgrounds that are so different to the vast majority of the population? What is clear is that an independent school education offers a tremendous boost to the life chances of young people, making it more likely that they will attain highly in school exams, attend the country’s leading universities and gain access to the highest and most prestigious professions. -

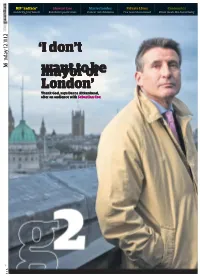

T Want to Be Mayor of London

RIP *sadface* Stewart Lee Mastectomies Private Lives Enonomics Celebrity grief tweets Rekebah’s poetic texts Cancer risk dilemma I’ve never been kissed Brian meets Ha-Joon Chang 1 2 1 . 1 . 1 2 y a ‘I don’t d n M o mayor want to of be London’ Thank God, says Decca Aitkenhead, after an audience with Sebastian Coe A 2 1 Shortcuts l i v e D u n n R I P C e s f o r a l l t h Eulogies t h a n k Gervais and Radio 1 DJ Greg James, n j o y m e n t o u r s o f e neither of whom I believe to have h D a d ’ s Reaping the w a t c h i n g been particular acquaintances of A r m y Nutkins, or, indeed, luminaries in Celebrity Death the wildlife-broadcasting world. Twitter Harvest Unless we count Flanimals. This year we have encountered the high-profile passings of Neil So sad to hear Armstrong, Tony Scott and Hal t is often suggested that the David, and naturally the coverage death of Diana, Princess of about Terry Nutkins. that followed them often drew on I Wales, altered the nature What an absolute celebrity tweets (“Everyone should of collective grief, rendering it icon go outside and look at the moon suddenly acceptable to line the tonight and give a thought to Neil streets, send flowers and, most Armstrong,” ordered McFly’s Tom importantly, weep publicly at the Fletcher). But few could match the death of someone you did not response that greeted the death of actually know.