1 Inflection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Perfect Tenses 8.Pdf

Name Date Lesson 7 Perfect Tenses Teaching The present perfect tense shows an action or condition that began in the past and continues into the present. Present Perfect Dan has called every day this week. The past perfect tense shows an action or condition in the past that came before another action or condition in the past. Past Perfect Dan had called before Ellen arrived. The future perfect tense shows an action or condition in the future that will occur before another action or condition in the future. Future Perfect Dan will have called before Ellen arrives. To form the present perfect, past perfect, and future perfect tenses, add has, have, had, or will have to the past participle. Tense Singular Plural Present Perfect I have called we have called has or have + past participle you have called you have called he, she, it has called they have called Past Perfect I had called we had called had + past participle you had called you had called he, she, it had called they had called CHAPTER 4 Future Perfect I will have called we will have called will + have + past participle you will have called you will have called he, she, it will have called they will have called Recognizing the Perfect Tenses Underline the verb in each sentence. On the blank, write the tense of the verb. 1. The film house has not developed the pictures yet. _______________________ 2. Fred will have left before Erin’s arrival. _______________________ 3. Florence has been a vary gracious hostess. _______________________ 4. Andi had lost her transfer by the end of the bus ride. -

Representation of Inflected Nouns in the Internal Lexicon

Memory & Cognition 1980, Vol. 8 (5), 415423 Represeritation of inflected nouns in the internal lexicon G. LUKATELA, B. GLIGORIJEVIC, and A. KOSTIC University ofBelgrade, Belgrade, Yugoslavia and M.T.TURVEY University ofConnecticut, Storrs, Connecticut 06268 and Haskins Laboratories, New Haven, Connecticut 06510 The lexical representation of Serbo-Croatian nouns was investigated in a lexical decision task. Because Serbo-Croatian nouns are declined, a noun may appear in one of several gram matical cases distinguished by the inflectional morpheme affixed to the base form. The gram matical cases occur with different frequencies, although some are visually and phonetically identical. When the frequencies of identical forms are compounded, the ordering of frequencies is not the same for masculine and feminine genders. These two genders are distinguished further by the fact that the base form for masculine nouns is an actual grammatical case, the nominative singular, whereas the base form for feminine nouns is an abstraction in that it cannot stand alone as an independent word. Exploiting these characteristics of the Serbo Croatian language, we contrasted three views of how a noun is represented: (1) the independent entries hypothesis, which assumes an independent representation for each grammatical case, reflecting its frequency of occurrence; (2) the derivational hypothesis, which assumes that only the base morpheme is stored, with the individual cases derived from separately stored inflec tional morphemes and rules for combination; and (3) the satellite-entries hypothesis, which assumes that all cases are individually represented, with the nominative singular functioning as the nucleus and the embodiment of the noun's frequency and around which the other cases cluster uniformly. -

On Root Modality and Thematic Relations in Tagalog and English*

Proceedings of SALT 26: 775–794, 2016 On root modality and thematic relations in Tagalog and English* Maayan Abenina-Adar Nikos Angelopoulos UCLA UCLA Abstract The literature on modality discusses how context and grammar interact to produce different flavors of necessity primarily in connection with functional modals e.g., English auxiliaries. In contrast, the grammatical properties of lexical modals (i.e., thematic verbs) are less understood. In this paper, we use the Tagalog necessity modal kailangan and English need as a case study in the syntax-semantics of lexical modals. Kailangan and need enter two structures, which we call ‘thematic’ and ‘impersonal’. We show that when they establish a thematic dependency with a subject, they express necessity in light of this subject’s priorities, and in the absence of an overt thematic subject, they express necessity in light of priorities endorsed by the speaker. To account for this, we propose a single lexical entry for kailangan / need that uniformly selects for a ‘needer’ argument. In thematic constructions, the needer is the overt subject, and in impersonal constructions, it is an implicit speaker-bound pronoun. Keywords: modality, thematic relations, Tagalog, syntax-semantics interface 1 Introduction In this paper, we observe that English need and its Tagalog counterpart, kailangan, express two different types of necessity depending on the syntactic structure they enter. We show that thematic constructions like (1) express necessities in light of priorities of the thematic subject, i.e., John, whereas impersonal constructions like (2) express necessities in light of priorities of the speaker. (1) John needs there to be food left over. -

Animacy, Definiteness, and Case in Cappadocian and Other

Animacy, definiteness, and case in Cappadocian and other Asia Minor Greek dialects* Mark Janse Ghent University and Roosevelt Academy, Middelburg This article discusses the relation between animacy, definiteness, and case in Cappadocian and several other Asia Minor Greek dialects. Animacy plays a decisive role in the assignment of Greek and Turkish nouns to the various Cappadocian noun classes. The development of morphological definiteness is due to Turkish interference. Both features are important for the phenom- enon of differential object marking which may be considered one of the most distinctive features of Cappadocian among the Greek dialects. Keywords: Asia Minor Greek dialectology, Cappadocian, Farasiot, Lycaonian, Pontic, animacy, definiteness, case, differential object marking, Greek–Turkish language contact, case typology . Introduction It is well known that there is a crosslinguistic correlation between case marking and animacy and/or definiteness (e.g. Comrie 1989:128ff., Croft 2003:166ff., Linguist List 9.1653 & 9.1726). In nominative-accusative languages, for in- stance, there is a strong tendency for subjects of active, transitive clauses to be more animate and more definite than objects (for Greek see Lascaratou 1994:89). Both animacy and definiteness are scalar concepts. As I am not con- cerned in this article with pronouns and proper names, the person and referen- tiality hierarchies are not taken into account (Croft 2003:130):1 (1) a. animacy hierarchy human < animate < inanimate b. definiteness hierarchy definite < specific < nonspecific Journal of Greek Linguistics 5 (2004), 3–26. Downloaded from Brill.com09/29/2021 09:55:21PM via free access issn 1566–5844 / e-issn 1569–9856 © John Benjamins Publishing Company 4 Mark Janse With regard to case marking, there is a strong tendency to mark objects that are high in animacy and/or definiteness and, conversely, not to mark ob- jects that are low in animacy and/or definiteness. -

An Analysis of Semantic and Syntactic Negation in Oshiwambo and English

JULACE: Journal of University of Namibia Language Centre Volume 4, No. 2, 2019 (ISSN 2026-8297) An analysis of semantic and syntactic negation in Oshiwambo and English Immanuel N. Shatepa1 Namibia University of Science and Technology Abstract Negation in languages has been documented since the 1970s and 1980s. This paper attempts to explain the negation structures in semantic and syntactic structures of Oshiwambo and English languages. These two languages have two complete negation structures and how they function to achieve negation is far from being similar. The focus of the paper was on the analysis of the sentential negation and how negative particles are used in English and Oshiwambo, a Bantu language. It analyzes and compares the use of full negatives, affixes and quasi negative words to achieve negation in English and Oshiwambo language. The Oshiwambo and English texts/contents were purposely sampled and content analysis was performed accordingly. The analysis shows that Bantu languages share a common rule of negation which is the use of a pre- initial prefix while the rules to changing negative imperative to interrogative or declarative are different between English and Oshiwambo. Keywords: pre-initial, negation, marker, imperative, declarative, integrative, syntactic, semantic, Bantu Introduction A number of studies on negation of English and Bantu languages have been conducted by linguists. Studies by Kim and Sag (1995); Neba and Tanda (2005) and Weir (2013) show that negation differs from language to language. They further state highlighted that since every language has its own morphological and semantic components to express negation, one rule fits all simply does not work. -

The Formation, Translation and Use of Participles in Latin, and the Nature of Relative Time

Chapter 23: Participles Chapter 23 covers the following: the formation, translation and use of participles in Latin, and the nature of relative time. At the end of the lesson we’ll review the vocabulary which you should memorize in this chapter. There are four important rules to remember in Chapter 23: (1) Latin has four participles: the present active, the future active; the perfect passive and the future passive. It lacks, however, a present passive participle (“being [verb]-ed”) and a perfect active participle (“having [verb]-ed”). (2) The perfect passive, future active and future passive participles belong to first/second declension. The present active participle belongs to third declension. (3) The verb esse has only a future active participle (futurus). It lacks both the present active and all passive participles. (4) Participles show relative time. What are participles? At heart, participles are verbs which have been turned into adjectives. Thus, technically participles are “verbal adjectives.” The first part of the word (parti-) means “part;” the second part (-cip-) means “take,” indicating that participles “partake, share” in the characteristics of both verbs and adjectives. In other words, the base of a participle is verbal, giving it some of the qualities of a verb, for instance, tense: it can indicate when the action is happening (now or then or later; i.e. present, past or future); conjugation: what thematic vowel will be used (e.g. -a- in first conjugation, -e- in second, and so on); voice: whether the word it’s attached to is acting or being acted upon (i.e. -

Classifiers: a Typology of Noun Categorization Edward J

Western Washington University Western CEDAR Modern & Classical Languages Humanities 3-2002 Review of: Classifiers: A Typology of Noun Categorization Edward J. Vajda Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/mcl_facpubs Part of the Modern Languages Commons Recommended Citation Vajda, Edward J., "Review of: Classifiers: A Typology of Noun Categorization" (2002). Modern & Classical Languages. 35. https://cedar.wwu.edu/mcl_facpubs/35 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Humanities at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in Modern & Classical Languages by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. J. Linguistics38 (2002), I37-172. ? 2002 CambridgeUniversity Press Printedin the United Kingdom REVIEWS J. Linguistics 38 (2002). DOI: Io.IOI7/So022226702211378 ? 2002 Cambridge University Press Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, Classifiers: a typology of noun categorization devices.Oxford: OxfordUniversity Press, 2000. Pp. xxvi+ 535. Reviewedby EDWARDJ. VAJDA,Western Washington University This book offers a multifaceted,cross-linguistic survey of all types of grammaticaldevices used to categorizenouns. It representsan ambitious expansion beyond earlier studies dealing with individual aspects of this phenomenon, notably Corbett's (I99I) landmark monograph on noun classes(genders), Dixon's importantessay (I982) distinguishingnoun classes fromclassifiers, and Greenberg's(I972) seminalpaper on numeralclassifiers. Aikhenvald'sClassifiers exceeds them all in the number of languages it examines and in its breadth of typological inquiry. The full gamut of morphologicalpatterns used to classify nouns (or, more accurately,the referentsof nouns)is consideredholistically, with an eye towardcategorizing the categorizationdevices themselvesin terms of a comprehensiveframe- work. -

The Term Declension, the Three Basic Qualities of Latin Nouns, That

Chapter 2: First Declension Chapter 2 covers the following: the term declension, the three basic qualities of Latin nouns, that is, case, number and gender, basic sentence structure, subject, verb, direct object and so on, the six cases of Latin nouns and the uses of those cases, the formation of the different cases in Latin, and the way adjectives agree with nouns. At the end of this lesson we’ll review the vocabulary you should memorize in this chapter. Declension. As with conjugation, the term declension has two meanings in Latin. It means, first, the process of joining a case ending onto a noun base. Second, it is a term used to refer to one of the five categories of nouns distinguished by the sound ending the noun base: /a/, /ŏ/ or /ŭ/, a consonant or /ĭ/, /ū/, /ē/. First, let’s look at the three basic characteristics of every Latin noun: case, number and gender. All Latin nouns and adjectives have these three grammatical qualities. First, case: how the noun functions in a sentence, that is, is it the subject, the direct object, the object of a preposition or any of many other uses? Second, number: singular or plural. And third, gender: masculine, feminine or neuter. Every noun in Latin will have one case, one number and one gender, and only one of each of these qualities. In other words, a noun in a sentence cannot be both singular and plural, or masculine and feminine. Whenever asked ─ and I will ask ─ you should be able to give the correct answer for all three qualities. -

Class Slides

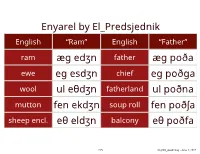

Enyarel by El_Predsjednik English “Ram” English “Father” ram æg edʒn father æg poða ewe eg esdʒn chief eg poðga wool ul eθdʒn fatherland ul poðna mutton fen ekdʒn soup roll fen poðʃa sheep encl. eθ eldʒn balcony eθ poðfa 215 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 HIGH VALYRIAN 216 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 The common language of the Valyrian Freehold, a federation in Essos that was destroyed by the Doom before the series begins. 217 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 218 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 ??????? High Valyrian ?????? 219 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Valar morghulis. “ALL men MUST die.” Valar dohaeris. “ALL men MUST serve.” 220 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Singular, Plural, Collective 221 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Number Marking Definite Indefinite Small Number Singular Large Number Collective Plural 222 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Number Marking Definite Indefinite Small Number Singular Paucal Large Number Collective Plural 223 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N kastor qintir “green turtle” 224 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N *val kaːr “man heap” 225 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N *valhaːr > *valhar > valar “all men” 226 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N *val ont > *valon > valun “man hand > some men” 227 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 SOUND CHANGE Dispreference for certain _# Cs, e.g. voiced stops, laterals, voiceless non- coronals, etc. 228 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 SOUND CHANGE Dispreference for monosyllabic words— especially -

Verbal Case and the Nature of Polysynthetic Inflection

Verbal case and the nature of polysynthetic inflection Colin Phillips MIT Abstract This paper tries to resolve a conflict in the literature on the connection between ‘rich’ agreement and argument-drop. Jelinek (1984) claims that inflectional affixes in polysynthetic languages are theta-role bearing arguments; Baker (1991) argues that such affixes are agreement, bearing Case but no theta-role. Evidence from Yimas shows that both of these views can be correct, within a single language. Explanation of what kind of inflection is used where also provides us with an account of the unusual split ergative agreement system of Yimas, and suggests a novel explanation for the ban on subject incorporation, and some exceptions to the ban. 1. Two types of inflection My main aim in this paper is to demonstrate that inflectional affixes can be very different kinds of syntactic objects, even within a single language. I illustrate this point with evidence from Yimas, a Papuan language of New Guinea (Foley 1991). Understanding of the nature of the different inflectional affixes of Yimas provides an explanation for its remarkably elaborate agreement system, which follows a basic split-ergative scheme, but with a number of added complications. Anticipating my conclusions, the structure in (1c) shows what I assume the four principal case affixes on a Yimas verb to be. What I refer to as Nominative and Accusative affixes are pronominal arguments: these inflections, which are restricted to 1st and 2nd person arguments in Yimas, begin as specifiers and complements of the verb, and incorporate into the verb by S- structure. On the other hand, what I refer to as Ergative and Absolutive inflection are genuine agreement - they are the spell-out of functional heads, above VP, which agree with an argument in their specifier. -

RELATIONAL NOUNS, PRONOUNS, and Resumptionw Relational Nouns, Such As Neighbour, Mother, and Rumour, Present a Challenge to Synt

Linguistics and Philosophy (2005) 28:375–446 Ó Springer 2005 DOI 10.1007/s10988-005-2656-7 ASH ASUDEH RELATIONAL NOUNS, PRONOUNS, AND RESUMPTIONw ABSTRACT. This paper presents a variable-free analysis of relational nouns in Glue Semantics, within a Lexical Functional Grammar (LFG) architecture. Rela- tional nouns and resumptive pronouns are bound using the usual binding mecha- nisms of LFG. Special attention is paid to the bound readings of relational nouns, how these interact with genitives and obliques, and their behaviour with respect to scope, crossover and reconstruction. I consider a puzzle that arises regarding rela- tional nouns and resumptive pronouns, given that relational nouns can have bound readings and resumptive pronouns are just a specific instance of bound pronouns. The puzzle is: why is it impossible for bound implicit arguments of relational nouns to be resumptive? The puzzle is highlighted by a well-known variety of variable-free semantics, where pronouns and relational noun phrases are identical both in category and (base) type. I show that the puzzle also arises for an established variable-based theory. I present an analysis of resumptive pronouns that crucially treats resumptives in terms of the resource logic linear logic that underlies Glue Semantics: a resumptive pronoun is a perfectly ordinary pronoun that constitutes a surplus resource; this surplus resource requires the presence of a resumptive-licensing resource consumer, a manager resource. Manager resources properly distinguish between resumptive pronouns and bound relational nouns based on differences between them at the level of semantic structure. The resumptive puzzle is thus solved. The paper closes by considering the solution in light of the hypothesis of direct compositionality. -

Chapter 1 Basic Categorial Syntax

Hardegree, Compositional Semantics, Chapter 1 : Basic Categorial Syntax 1 of 27 Chapter 1 Basic Categorial Syntax 1. The Task of Grammar ............................................................................................................ 2 2. Artificial versus Natural Languages ....................................................................................... 2 3. Recursion ............................................................................................................................... 3 4. Category-Governed Grammars .............................................................................................. 3 5. Example Grammar – A Tiny Fragment of English ................................................................. 4 6. Type-Governed (Categorial) Grammars ................................................................................. 5 7. Recursive Definition of Types ............................................................................................... 7 8. Examples of Types................................................................................................................. 7 9. First Rule of Composition ...................................................................................................... 8 10. Examples of Type-Categorial Analysis .................................................................................. 8 11. Quantifiers and Quantifier-Phrases ...................................................................................... 10 12. Compound Nouns