The Violin in Music Therapy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bill in Congress Threatens Federal Aid to College IS Educators Nationwide Line up Against Impositions on Freedom of Speech, Academic Freedom by THOMAS F

"No News Is Good News"' Founded 1957, Incorporated 1976 Volume XXXVIII, Number 63 Monday, July 31, 1995 First Copy Frsee Bill in Congress Threatens Federal Aid to College IS Educators Nationwide Line Up Against Impositions On Freedom of Speech, Academic Freedom BY THOMAS F. MASSE distributed to political crippling to Stony Brook. Kenny affect all form of government amendment include the NYPIRG, Statesman Editor organizations or groups that try to said that Stony Brook receives moneys, including NIH research SASU, USSA, the College With the SUNY/CUNY influence public opinion, all more than $100 million in contracts, federal student loans, Republicans, religious organizations, system still reeling from the federal funding will be cut from research grants, a large portion of and grants such as Pell Grants. women's organizations, minority impact of the recent New York those institutions. which is federal money. Kenny Groups that could be organizations, newspapers, and budget fight, the U.S. Congress Such an amendment could be also said that the amendment may categorized as falling under the others. is poised to deliver another In essence, according to devastating blow. a. LIMITATION ON USE OF FUNDS. - None of the funds Kenny, if Stony Brook collected Representative Ernest J. moneys and Polity gave them to Istook (R-Okla.), proposed an appropriated in this Act may be made available to any any of the above groups, Stony amendment to a Labor, Health institution of higher education when it is made known Brook could be without tens of and Human Services, and to the Federal official having authority to obligate or millions of research dollars and Education bill that will cut off- expend such funds that any amount, derived from students could be without loans federal funding to institutions of and grants. -

The Stony Brook Statesman

THE STONY BROOK STATESMAN State University of New York at Stony Brook Stony Brook, New York Vol. 39, Nos. 1 - 66 August 28, 1995 - August 12, 1996 NOTES ON ISSUE NUMBERS FOR VOL. 39 No. 12, Oct. 12, 1995, is misnumbered "11" No. 14, Oct. 19, 1995, is misnumbered "63" No. 49, March 25, 1996 is misnumbered "50" 2 CampIS Caleldar:Whaat's For the very latest information regarding Opening survival," a group discussion for commuting students. To Locaited in the Football Stadium, 9:00 p.m.- 2:00 a.m. Week Activities, please call 632-6821. This service is be held in-the Bi-level of the Student-Union, 8:00-p.m. - In thie event of rain,- the-movie will be shown in the provided 24 hours a day. 9:00p.m. : Pritchard Gym, Indoor Sports Complex. Monday, August 28 Tuesday, August 29 Wednesday, August 30 First day of classes. Late registration begins with A plant sale will be held in the Lobby of the Student A plant and pottery sale will be held in the-Lobby of $30- late fee assessed. Union, 10:00 a.m. - 3:00 p.m. - carpetPA sale will take place between James and A carpet sale will be held outside the Dining Center Ammann Colleges, Kelly and Roosevelt Quads, and of Kelly Quad, 10:00 a.m. - 5:00 p.m. Tabler Quad. 10:00 a.m.'- 5:00 p.m. There will be a poster sale in the Union Fireside 'On September 3, 1783, the American Revolution There will be -a poster sale in the Union Fireside Lounge, Student Union, from 10:00 a.m. -

Performance-Practice Issues in Bartók's Sonata

PERFORMANCE-PRACTICE ISSUES IN BARTÓK‘S SONATA FOR SOLO VIOLIN (1944) by OLIVER YATSUGAFU (Under the Direction of Levon Ambartsumian and David Haas) ABSTRACT The Sonata for Solo Violin was composed by Béla Bartók in 1944 as a commission by the American violinist Yehudi Menuhin. The piece represents one of Bartók‘s last works. This Solo Sonata is a four-movement work with the following movements: ―Tempo di ciaccona,‖ ―Fuga,‖ ―Melodia,‖ and ―Presto.‖ The entire piece is approximately twenty minutes in length. The Solo Sonata stands as one of the most important 20th-century compositions for solo violin. The author has investigated the circumstances in which the Solo Sonata was created and its performance-practice issues. Therefore, this dissertation discusses Bartók‘s life and work in the United States of America, his encounter with Yehudi Menuhin, and the compositional history, performances, and reviews of the Solo Sonata. In addition, this document analyses briefly the form, style, and performance-practice challenges of each movement, appointing possible solutions. INDEX WORDS: Béla Bartók, Sonata for Solo Violin, violin performance-practice issues, repertoire for solo violin, revisions, Solo Sonata creation, Solo Sonata form and style, Yehudi Menuhin, Rudolf Kolisch. PERFORMANCE-PRACTICE ISSUES IN BARTÓK‘S SONATA FOR SOLO VIOLIN (1944) by OLIVER YATSUGAFU B. M. in Violin Performance FORB, Parana School of Higher Studies of Music and Fine Arts, Brazil, 2001 M.M. in Violin Performance University of Georgia, GA, United States 2007 A Dissertation -

Classical Gas Recordings and Releases Releases of “Classical Gas” by Mason Williams

MasonMason WilliamsWilliams Full Biography with Awards, Discography, Books & Television Script Writing Releases of Classical Gas Updated February 2005 Page 1 Biography Mason Williams, Grammy Award-winning composer of the instrumental “Classical Gas” and Emmy Award-winning writer for “The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour,” has been a dynamic force in music and television circle since the 1960s. Born in Abilene, Texas in 1938, Williams spent his youth divided between living with his 1938 father in Oklahoma and his mother in Oregon. His interest in music began when, as a teenager, he to 1956 became a fan of pop songs on the radio and sang along with them for his own enjoyment. In high Oklahoma school, he sang in the choir and formed his first group, an a capella quartet that did the 1950’s City style pop and rock & roll music of the era. They called themselves The Imperials and The to L.A. Lamplighters. The other group members were Diana Allen, Irving Faught and Larry War- ren. After Williams was graduated from Northwest Classen High School in Oklahoma City in 1956, he and his lifelong friend, artist Edward Ruscha, drove to Los Angeles. There, Williams attended Los Angeles City College as a math major, working toward a career as an insurance actuary. But he spent almost as much time attending musical events, especially jazz clubs and concerts, as he did studying. This cultural experience led him to drop math and seek a career in music. Williams moved back to Oklahoma City in 1957 to pursue his interest in music by taking a crash course in piano for the summer. -

Nine Constructions of the Crossover Between Western Art and Popular Musics (1995-2005)

Subject to Change: Nine constructions of the crossover between Western art and popular musics (1995-2005) Aliese Millington Thesis submitted to fulfil the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ~ Elder Conservatorium of Music Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences The University of Adelaide October 2007 Contents List of Tables…..…………………………………………………………....iii List of Plates…………………………………………………………….......iv Abstract……………………………………………………………………...v Declaration………………………………………………………………….vi Acknowledgements………………………………………………………...vii Chapter One Introduction…………………………………..…..1 Chapter Two Crossover as a marketing strategy…………....…43 Chapter Three Crossover: constructing individuality?.................69 Chapter Four Shortcuts and signposts: crossover and media themes..…………………...90 Chapter Five Evoking associations: crossover, prestige and credibility………….….110 Chapter Six Attracting audiences: alternate constructions of crossover……..……..135 Chapter Seven Death and homogenization: crossover and two musical debates……..……...160 Chapter Eight Conclusions…………………..………………...180 Appendices Appendix A The historical context of crossover ….………...186 Appendix B Biographies of the four primary artists..…….....198 References …...……...………………………………………………...…..223 ii List of Tables Table 1 Nine constructions of crossover…………………………...16-17 iii List of Plates 1 Promotional photograph of bond reproduced from (Shine 2002)……………………………………….19 2 Promotional photograph of FourPlay String Quartet reproduced from (FourPlay 2007g)………………………………….20 3 Promotional -

Violin Syllabus / 2013 Edition

VVioliniolin SYLLABUS / 2013 EDITION SYLLABUS EDITION © Copyright 2013 The Frederick Harris Music Co., Limited All Rights Reserved Message from the President The Royal Conservatory of Music was founded in 1886 with the idea that a single institution could bind the people of a nation together with the common thread of shared musical experience. More than a century later, we continue to build and expand on this vision. Today, The Royal Conservatory is recognized in communities across North America for outstanding service to students, teachers, and parents, as well as strict adherence to high academic standards through a variety of activities—teaching, examining, publishing, research, and community outreach. Our students and teachers benefit from a curriculum based on more than 125 years of commitment to the highest pedagogical objectives. The strength of the curriculum is reinforced by the distinguished College of Examiners—a group of fine musicians and teachers who have been carefully selected from across Canada, the United States, and abroad for their demonstrated skill and professionalism. A rigorous examiner apprenticeship program, combined with regular evaluation procedures, ensures consistency and an examination experience of the highest quality for candidates. As you pursue your studies or teach others, you become not only an important partner with The Royal Conservatory in the development of creativity, discipline, and goal- setting, but also an active participant, experiencing the transcendent qualities of music itself. In a society where our day-to-day lives can become rote and routine, the human need to find self-fulfillment and to engage in creative activity has never been more necessary. -

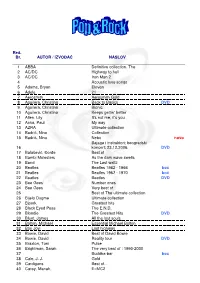

Red. Br. AUTOR / IZVOĐAČ NASLOV 1 ABBA Definitive Collection. the 2

Red. Br. AUTOR / IZVO ĐAČ NASLOV 1 ABBA Definitive collection. The 2 AC/DC Highway to hell 3 AC/DC Iron Man 2 4 Acoustic love songs 5 Adams, Bryan Eleven 6 Adele 21 7 Aerosmith Aerosmith Gold 8 Aguilera, Christina Back to Basics DVD 9 Aguilera, Christina Bionic 10 Aguilera, Christina Keeps gettin' better 11 Allen, Lily It's not me, it's you 12 Anka, Paul My way 13 AZRA Ultimate collection 14 Badri ć, Nina Collection 15 Badri ć, Nina Nebo novo Bajaga i instruktori; beogradski 16 koncert; 23.12.2006. DVD 17 Balaševi ć, Đor đe Best of 18 Bambi Molesters As the dark wave swells 19 Band The Last waltz 20 Beatles Beatles 1962 - 1966 box 21 Beatles Beatles 1967 - 1970 box 22 Beatles Beatles DVD 23 Bee Gees Number ones 24 Bee Gees Very best of 25 Best of The ultimate collection 26 Bijelo Dugme Ultimate collection 27 Bjoerk Greatest hits 28 Black Eyed Peas The E.N.D. 29 Blondie The Greatest Hits DVD 30 Blunt, James All the lost souls 31 Bolton, Michael Essential Michael Bolton 32 Bon Jovi Lost highway 33 Bowie, David Best of David Bowie 34 Bowie, David Reality tour DVD 35 Braxton, Toni Pulse 36 Brightman, Sarah The very best of : 1990-2000 37 Buddha-bar box 38 Cale, J. J. Gold 39 Cardigans Best of... 40 Carey, Mariah, E=MC2 41 Cetinski, Toni Ako to se zove ljubav 42 Cetinski, Toni Arena live 2008 DVD 43 Cetinski, Toni Triptonyc 44 Cetinski, Toni The Best of 2CD 45 Cher Gold 46 Cinquetti, Gigliola Chiamalo amore.. -

An Investigation of Audio Signal-Driven Sound Synthesis with a Focus on Its Use for Bowed Stringed Synthesisers

AN INVESTIGATION OF AUDIO SIGNAL-DRIVEN SOUND SYNTHESIS WITH A FOCUS ON ITS USE FOR BOWED STRINGED SYNTHESISERS by CORNELIUS POEPEL A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Music The University of Birmingham June 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Contents 1 Introduction 1 2 Motivation 10 2.1 Personal Experiences . 10 2.2 Using Potentials . 14 2.3 Human-Computer Interaction in Music . 15 3 Design of Interactive Digital Audio Systems 21 3.1 From Idea to Application . 24 3.2 System Requirements . 26 3.3 Formalisation . 30 3.4 Specification . 32 3.5 Abstraction . 33 3.6 Models . 36 3.7 Formal Specification . 39 3.8 Verification . 41 4 Related Research 44 4.1 Research Field . 44 i CONTENTS ii 4.1.1 Two Directions in the Design of Musical Interfaces . 46 4.1.2 Controlling a Synthesis Engine . 47 4.1.3 Building an Interface for a Trained Performer . 48 4.2 Computer-Based Stringed Instruments . 49 4.3 Using Sensors . -

Music for These Times,Bringing in the New Year of 2018,Merry

Music For These Times Music Inside So the world is on fire right now. Stock markets are collapsing, a pandemic is raging across the globe, a buffoon is occupying the role of “Leader of the Free World,” and our supermarkets are out of toilet paper and hand sanitizer. But things could be worse – we could be in a Groundhog Day time loop living the same day over and over again. So we need some music for these times. Billy Joel has long been one of my favorite musicians and a personal hero. He grew up in Hicksville, Long Island, New York, just about six miles from my hometown of Farmingdale and seven years ahead of me. I’ve always seen him as a hometown boy who did good. So in keeping with music for these times, I offer his awesome hit “We Didn’t Start The Fire,” complete with historically accurate images. Billy Joel – “We Didn’t Start The Fire” Just remember; we could be living this same day over and over again until we get it right. Related Posts A New American! This and That, Halloween Edition My Remembrance of September Eleven Bringing In The New Year of 2018 Happy New Year 2018 Happy New year of 2018 everyone! We all survived the horrors of 2017, with a promise that 2018 will be a better year for everyone. So, to ring in the new year properly we need a bit of holiday music. For the new year of 2018, I think this lovely piece of music speaks for hopes of better times ahead. -

Reading Vanessa-Mae Vanessa-Mae Was Born in Singapore in 1978

Англійська мова 8 клас Дорогі діти! В зв’язку з продовженням карантину ми з Вами й надалі працюватимемо дистанційно. Бережіть себе!!! 27 – 30 квітня Протягом цього тижня Вам слід буде опрацювати вправи та виконати семестрову контрольну роботу з читання. Зверніть увагу, що виконану контрольну роботу Вам слід буде надіслати мені до 03 травня! 1. Ex.1 p. 200 – Усно. Прочитати назви країн, пригадати їх столиці. Назвати материки 2. Ex.2 p. 200 – Усно. Дати відповіді на подані запитання, використовуючи слова на наступній сторінці 3. “ Remember” p. 201 – повторити граматичний матеріал, про вживання означеного артикля the 4. Ex.3 p.201 -202 – Письмово. Доповнити подані речення, вживаючи означений артикль, або залишити без змін ( якщо артикль не вживаємо – то ставим “ - ’’ 5. Виконуємо контрольну роботу. Слід прочитати текст та виконати завдання після нього Reading Vanessa-Mae Vanessa-Mae was born in Singapore in 1978. She moved to England with her mother when she was four. Vanessa was already having piano lessons when she started playing the violin as well. At the age of eight Vanessa went to Beijing in China to study the violin. The course takes normal students three years to complete, but Vanessa finished it in six months. While she was studying in Beijing, she visited some interesting places like the Great Wall of China and the Emperor’s Palace. She remembers that the Chinese she met were very surprised that she couldn’t speak a word Chinese. Vanessa began performing when she was ten years old, and at 11 she entered the Royal Academy of Music. While she was studying there she played with the London Philharmonic Orchestra and went on tour with the London Mozart Players. -

RHSSUE '.'' a BILLBOARD SPOTLIGHT I' SEE PAGE 71 I 1,1Ar 1.1141101 101611.C, the Essential Electronic .' Music Collection

$5.95 (U.S.), $6.95 (CAN.), £4.95 (U.K.), Y2,500 (JAPAN) IN MUSIC NEWS IBXNCCVR **** * ** 3 -DIGIT 908 1190807GEE374EM0021 BLBD 576 001 032198 2 126 1256 3740 ELM A LONG BEACH CA 90807 Fogerty Is Back With Long- Awaited WB Set PAGE 11 THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC, VIDEO AND HOME ENTERTAINMENT r APRIL 19, 1997 ADVERTISEMENTS Labels Testing Chinese Mkt. Urban Acts Put New Spin Liaison Offices Offer Domestic Link BY GEOFF BURPEE pendents: America's Cherry Lane On Spoken -Word Genre Music, Taiwan's Rock Records, and HONG KONG -As a means of Hong Kong's Fitto. However, these BY J.R. REYNOLDS itual enrichment. establishing and testing ties within companies (and others that would Labels are bowing projects by China's sprawling, underdeveloped like a presence) must r e c o g n i z e LOS ANGELES -A wave of releas- such young hip -hop and alternative - recording restraints on es by African- American spoken -word influenced artists as Keplyn and industry, their activi- acts will soon Mike Ladd, a- the "repre- SONY ties, such as begin flowing longside product sentative" EMI state con- through the retail by pre- hip -hop or "liaison" trols on lic- pipeline, as labels poets like Sekou office is be- ensing music attempt to tap Sundiata and coming an increasingly from outside of China and into growing con- such early -'70s valuable tool for interna- SM the lack of a developed sumer interest in spoken -word pio- tional music companies market within. the specialized neers as the Last Such units also serve as an As early as 1988, major recording genre. -

It's a Balancing Act. That's the Secret to Making This Music Fit in Today

“It’s a balancing act. That’s the secret to making this music fit in today”: Negotiating Professional and Vernacular Boundaries in the Cape Breton Fiddling Tradition by Ian Hayes A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Music Memorial University of Newfoundland January 2015 St. John’s, Newfoundland Abstract Originating from the music of early Gaelic immigrants, Cape Breton fiddling has been a thriving musical tradition for more than two hundred years. It eventually rose to prominence in the 1990s, receiving international recognition in the music industry. As the “Celtic boom” faded and major record labels lost interest in the tradition commercially, Cape Breton traditional musicians continued to maintain a presence in the music industry, though their careers now enjoy more modest success. All the while, Cape Breton fiddling has remained a healthy, vibrant tradition on the local level, where even the most commercially successful musicians have remained closely tied to their roots. This thesis examines how Cape Breton traditional musicians negotiate and express their musical identities in professional and vernacular contexts. As both professional musicians and tradition bearers, they are fixtures in popular culture, as well as the local music scene, placing them at an intersection between global and local culture. While seemingly fairly homogenous, Cape Breton fiddling is rich and varied tradition, and musicians relate to it in myriad ways. This plurality and intersubjectivity of what is considered to be “legitimate” culture is evident as the boundaries of tradition are drawn and change according to context.