Ellen Millender

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Program | Abstracts | Lecturers

11 March 2021 International conference ‘NATIONAL FORGETTING AND MEMORY: THE DESTRUCTION OF "NATIONAL" MONUMENTS FROM A COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE’ Program | Abstracts | Lecturers Organised by NISE and the Museum at the Yser In cooperation with: INDEX OF LECTURES KEY NOTE 1. Monumentality and Its Discontents: How the Past is Unforgotten. A. Rigney SESSION 1. Nation vs Regional vs Local Memories Chaired by Bruno De Wever City Monuments in Contemporary Kharkiv: Construction of the National and Regional Memory. V. Sukovata Nationalising Scorched Earth – Memory and destruction of monuments from Vukovar to Knin. M. Piasek Fascist monuments and their divided memories in Trieste and Bolzano. I. Pupella-Noguès SESSION 2. Nation-state, ideology and monuments Chaired by Chantal Kesteloot Reactions and counter reactions: The removal of Hoxha’s monuments and Albania’s tortuous transition. K. Këlliçi Present absence or absent presence. Monuments dedicated to the Yugoslav partisan struggle between future present and present perfect. L. Lovrenčić. and T. Pupovac «War on monuments» in Poland and its implications for the national historical policy. M. Pavlova KEY NOTE 2. Animated Stones: drawing a picture of the “IJzertoren’s” destruction via the lens of editorial cartoons. K. Swerts SESSION 3. Global and contemporary perspectives Chaired by K. Swerts A Knee on the Neck: Problematic Commemorative Practices in the United States. K. Shelby Set in Stone? Monuments, National Identity & John A. Macdonald. C. Spicer A Fractured Door: The Contested History of the IRS. J. Dawson Portraying and preserving the South African past – a monumental challenge. A. Bailey SESSION 4. The politics of resurrection Chaired by Marnix Beyen Staged reconstruction: On the scenography of the IJzertoren’s building site. -

Female Property Ownership and Status in Classical and Hellenistic Sparta

Female Property Ownership and Status in Classical and Hellenistic Sparta Stephen Hodkinson University of Manchester 1. Introduction The image of the liberated Spartiate woman, exempt from (at least some of) the social and behavioral controls which circumscribed the lives of her counterparts in other Greek poleis, has excited or horrified the imagination of commentators both ancient and modern.1 This image of liberation has sometimes carried with it the idea that women in Sparta exercised an unaccustomed influence over both domestic and political affairs.2 The source of that influence is ascribed by certain ancient writers, such as Euripides (Andromache 147-53, 211) and Aristotle (Politics 1269b12-1270a34), to female control over significant amounts of property. The male-centered perspectives of ancient writers, along with the well-known phenomenon of the “Spartan mirage” (the compound of distorted reality and sheer imaginative fiction regarding the character of Spartan society which is reflected in our overwhelmingly non-Spartan sources) mean that we must treat ancient images of women with caution. Nevertheless, ancient perceptions of their position as significant holders of property have been affirmed in recent modern studies.3 The issue at the heart of my paper is to what extent female property-holding really did translate into enhanced status and influence. In Sections 2-4 of this paper I shall approach this question from three main angles. What was the status of female possession of property, and what power did women have directly to manage and make use of their property? What impact did actual or potential ownership of property by Spartiate women have upon their status and influence? And what role did female property-ownership and status, as a collective phenomenon, play within the crisis of Spartiate society? First, however, in view of the inter-disciplinary audience of this volume, it is necessary to a give a brief outline of the historical context of my discussion. -

Marathon 2,500 Years Edited by Christopher Carey & Michael Edwards

MARATHON 2,500 YEARS EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS BULLETIN OF THE INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SUPPLEMENT 124 DIRECTOR & GENERAL EDITOR: JOHN NORTH DIRECTOR OF PUBLICATIONS: RICHARD SIMPSON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS PROCEEDINGS OF THE MARATHON CONFERENCE 2010 EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 2013 The cover image shows Persian warriors at Ishtar Gate, from before the fourth century BC. Pergamon Museum/Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin. Photo Mohammed Shamma (2003). Used under CC‐BY terms. All rights reserved. This PDF edition published in 2019 First published in print in 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN: 978-1-905670-81-9 (2019 PDF edition) DOI: 10.14296/1019.9781905670819 ISBN: 978-1-905670-52-9 (2013 paperback edition) ©2013 Institute of Classical Studies, University of London The right of contributors to be identified as the authors of the work published here has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Designed and typeset at the Institute of Classical Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory note 1 P. J. Rhodes The battle of Marathon and modern scholarship 3 Christopher Pelling Herodotus’ Marathon 23 Peter Krentz Marathon and the development of the exclusive hoplite phalanx 35 Andrej Petrovic The battle of Marathon in pre-Herodotean sources: on Marathon verse-inscriptions (IG I3 503/504; Seg Lvi 430) 45 V. -

Curriculum Back Up

Thucydides and Euripides: The Changing Civic and Moral Values during the Peloponnesian War Mary Ann T. Natunewicz INTRODUCTION This unit is part of a two-semester course taken by tenth graders in the second half of the school year. The course is team-taught by an art teacher and by a language teacher, with one nine-week semester devoted to art and the other nine-week semester to Greek literature, mythology and history. The school is on an accelerated block schedule and the class meets every day for 90 minutes. Smaller sections of this unit could be used in the Ancient History part of a World History course or a literature course that included Greek tragedy. The unit described below is in the literature semester of the course. It has been preceded by a three-week unit on Greek mythology. It will be followed by two weeks spent reading other Greek drama. The approximate length of the unit is four weeks. DISCUSSION OF THE UNIT One of the most fascinating periods that can be studied is fifth century B.C. Greece. So much was happening–painting and sculpture were flowering, scientists and philosophers were speculating on the nature of the universe, playwrights vied with one another in the dramatic contests, storytellers and poets were in demand, citizens were actively involved in running many states and historians were grappling with the significance of both ancient and current events. But what happens when a world war envelops this flourishing culture? What changes occur in individuals and in states? The general aim of this curriculum is to examine the view of late fifth century B.C. -

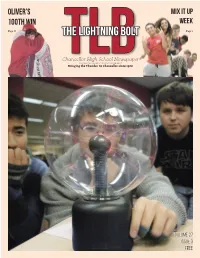

The Lightning Bolt Page 2

Oliver’s Mix It Up 100th win Week Page 17 The Lightning Bolt Page 2 Chancellor High School Newspaper TLB6300 Harrison Road, Fredericksburg, VA 22407 Bringing the Thunder to Chancellor since 1988 Volume 27 Issue 3 FREE 1 November 2014 what IS HAPPENING? Photo by Neil Schubel Neil Photo by Kids flocked to Mix It Up tables during lunch to take their pledge. Mix It Up week challenges kids to identify, cross and challenge social boundaries. Many students took thier pledge to mix it up in the week of November 10th till the 14th. Photo by Yearbook Staff Yearbook Photo by Photo by Neil Schubel Neil Photo by Schubel Neil Photo by Schubel Neil Photo by Tyler Jacobs models his painted Kenneth Ryan was spotted in the Jamie Smith in the process of a Joshua Edney jumps in the air in cheek in Mix It Up Week. halls with a fake skull. painted heart in Mix It Up Week. excitement. Photo courtesy of April Kniebbe April of Photo courtesy Nostalgia November! Who remembers the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge? The football coaches certainly do as they accepted the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge this July. A few players dumped the buckets as the team stood around to watch their coaches get ice buckets dumped on their heads. November 2014 2 Contents Editorial By Neil Schubel coming of winter if you look to by Chancellor’s Sociology Class Mrs. Gattie Editor-in-Chief some cases in states like New was also a huge success as near- Adviser It will ruin the happiest of York that are getting up to four ly 800 students took the pledge mornings waking up and realiz- feet of snow). -

Spartans a New History Pdf

Spartans a new history pdf Continue For those who study or teach the ancient world but are not a disciple of ancient Sparta, Nigel Kennell has written a paper to bridge the gap between Sparta's general concept and what experts believe. He argues that this is appropriate, given the fact that while the myth of Sparta is slowly collapsing (graphic novels and films like 300 might suggest otherwise), the new picture is far more fragmentary and complex than we might imagine. Kennenell's book tries to emphasize advances in our knowledge, reconcile, where possible, contradictory explanations, and often recognize that the state of our knowledge excludes consistent and convincing conclusions. The book begins with a brief discussion of the geography/topography of the region; the brevity of this section is perhaps the clearest indicator of the lack of systematic archaeology in the region. The more well-known and subject of most of the chapter are the twelve main sources of written or epigraphic evidence that Cannell examines (and evaluates) in chronological order. While all literary sources have contributed to the Spartan myth, Cannell acknowledges that Plutarch is probably the main culprit. The second chapter, the Sons of Hercules, tries to reconcile conflicts in the myths of Spartan origin with the evidence presented by archaeology. Cannell argues that, while the Spartans themselves may have reconciled Heraclid's return to Dorian's invasion, archaeological records and linguistic evidence are milit against a consistent explanation. Kennell is more confident in the archaeological records of the eighth century, during which, he said, Laconia was and remained sparsely populated, almost exclusively in the settlements of the Eurotas Valley in Sparta and Aiklae. -

Politics and Policy in Corinth 421-336 B.C. Dissertation

POLITICS AND POLICY IN CORINTH 421-336 B.C. DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University by DONALD KAGAN, B.A., A.M. The Ohio State University 1958 Approved by: Adviser Department of History TABLE OF CONTENTS Page FOREWORD ................................................. 1 CHAPTER I THE LEGACY OF ARCHAIC C O R I N T H ....................7 II CORINTHIAN DIPLOMACY AFTER THE PEACE OF NICIAS . 31 III THE DECLINE OF CORINTHIAN P O W E R .................58 IV REVOLUTION AND UNION WITH ARGOS , ................ 78 V ARISTOCRACY, TYRANNY AND THE END OF CORINTHIAN INDEPENDENCE ............... 100 APPENDIXES .............................................. 135 INDEX OF PERSONAL N A M E S ................................. 143 BIBLIOGRAPHY ........................................... 145 AUTOBIOGRAPHY ........................................... 149 11 FOREWORD When one considers the important role played by Corinth in Greek affairs from the earliest times to the end of Greek freedom it is remarkable to note the paucity of monographic literature on this key city. This is particular ly true for the classical period wnere the sources are few and scattered. For the archaic period the situation has been somewhat better. One of the first attempts toward the study of Corinthian 1 history was made in 1876 by Ernst Curtius. This brief art icle had no pretensions to a thorough investigation of the subject, merely suggesting lines of inquiry and stressing the importance of numisihatic evidence. A contribution of 2 similar score was undertaken by Erich Wilisch in a brief discussion suggesting some of the problems and possible solutions. This was followed by a second brief discussion 3 by the same author. -

Determining the Significance of Alliance Athologiesp in Bipolar Systems: a Case of the Peloponnesian War from 431-421 BCE

Wright State University CORE Scholar Browse all Theses and Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2016 Determining the Significance of Alliance athologiesP in Bipolar Systems: A Case of the Peloponnesian War from 431-421 BCE Anthony Lee Meyer Wright State University Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all Part of the International Relations Commons Repository Citation Meyer, Anthony Lee, "Determining the Significance of Alliance Pathologies in Bipolar Systems: A Case of the Peloponnesian War from 431-421 BCE" (2016). Browse all Theses and Dissertations. 1509. https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all/1509 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Browse all Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DETERMINING THE SIGNIFICANCE OF ALLIANCE PATHOLOGIES IN BIPOLAR SYSTEMS: A CASE OF THE PELOPONNESIAN WAR FROM 431-421 BCE A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts By ANTHONY LEE ISAAC MEYER Dual B.A., Russian Language & Literature, International Studies, Ohio State University, 2007 2016 Wright State University WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES ___April 29, 2016_________ I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Anthony Meyer ENTITLED Determining the Significance of Alliance Pathologies in Bipolar Systems: A Case of the Peloponnesian War from 431-421 BCE BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Arts. ____________________________ Liam Anderson, Ph.D. -

Copyrighted Material

9781405129992_6_ind.qxd 16/06/2009 12:11 Page 203 Index Acanthus, 130 Aetolian League, 162, 163, 166, Acarnanians, 137 178, 179 Achaea/Achaean(s), 31–2, 79, 123, Agamemnon, 51 160, 177 Agasicles (king of Sparta), 95 Achaean League: Agis IV and, agathoergoi, 174 166; as ally of Rome, 178–9; Age grades: see names of individual Cleomenes III and, 175; invasion grades of Laconia by, 177; Nabis and, Agesilaus (ephor), 166 178; as protector of perioecic Agesilaus II (king of Sparta), cities, 179; Sparta’s membership 135–47; at battle of Mantinea in, 15, 111, 179, 181–2 (362 B.C.E.), 146; campaign of, in Achaean War, 182 Asia Minor, 132–3, 136; capture acropolis, 130, 187–8, 192, 193, of Phlius by, 138; citizen training 194; see also Athena Chalcioecus, system and, 135; conspiracies sanctuary of after battle of Leuctra and, 144–5, Acrotatus (king of Sparta), 163, 158; conspiracy of Cinadon 164 and, 135–6; death of, 147; Acrotatus, 161 Epaminondas and, 142–3; Actium, battle of, 184 execution of women by, 168; Aegaleus, Mount, 65 foreign policy of, 132, 139–40, Aegiae (Laconian), 91 146–7; gift of, 101; helots and, Aegimius, 22 84; in Boeotia, 141; in Thessaly, Aegina (island)/Aeginetans: Delian 136; influence of, at Sparta, 142; League and,COPYRIGHTED 117; Lysander and, lameness MATERIAL of, 135; lance of, 189; 127, 129; pro-Persian party on, Life of, by Plutarch, 17; Lysander 59, 60; refugees from, 89 and, 12, 132–3; as mercenary, Aegospotami, battle of, 128, 130 146, 147; Phoebidas affair and, Aeimnestos, 69 102, 139; Spartan politics and, Aeolians, -

2013 Winter Athletic Awards Ceremony Wednesday, Ma

The Loomis Chaffee School 2012-2013 Winter Athletic Awards Ceremony Wednesday, March 27, 2013 Alpine Skiing Boys Basketball Girls Basketball Boys Hockey Girls Hockey Boys Swimming Girls Swimming Boys Squash Girls Squash Wrestling Loomis Chaffee Winter Athletic Awards Ceremony Wednesday, March 27, 2013 6:30 p.m. Loomis Dining Hall Tonight’s Program Welcome Remarks: Bob Howe ’80, Athletic Director Alpine Skiing: Jake Leyden Girls Squash: Naomi Appel Boys Squash: Elliot Beck Girls Swimming: Bob DeConinck Boys Swimming: Fred Seebeck Girls Hockey Liz Leyden Boys Hockey John Zavisza Boys Basketball Jim Dargati ‘85 Girls Basketball Adrian Stewart ‘90 Wrestling Ben Haldeman 2012-2013 Winter Athletic Award Winners Alpine Skiing All New England: Tucker Santoro, Sara Corsetti Most Valuable Skiier: Tucker Santoro Coaches’ Award: Theodora Cohen Boys Varsity Basketball All New England: Joe Stortini Coaches’ Award: Durelle Napier Coaches’ Award: Dale Reese Most Valuable Player: Joe Stortini Girls Varsity Basketball All New England: Steph Jones and Abby Pyne Most Valuable Player: Steph Jones Most Improved: Chynna Bailey Coaches’ Award: Brooke Marchitto Boys Varsity Hockey U.S.HR Prep School Player of the Year Danny Tirone All New England Team: Danny Tirone Most Valuable Player: Danny Tirone Coaches’ Award: EJ Culhane Coaches’ Award: Nick Miceli Golden Buoy: Stephen Picard Girls Varsity Hockey Coaches’ Award: Brittany Bugalski Coaches’ Award: Molly Strabley Boys Varsity Squash Most Valuable Player: Alex Steel Most Improved Player: Kevin Cha Coaches’ Award: -

Περίληψη : Spartan Admiral of the Peloponnesian Fleet During 411- 410 B.C

IΔΡΥΜA ΜΕΙΖΟΝΟΣ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΣΜΟΥ Συγγραφή : Ντόουσον Μαρία - Δήμητρα Μετάφραση : Ντόουσον Μαρία-Δήμητρα , Καμάρα Αφροδίτη Για παραπομπή : Ντόουσον Μαρία - Δήμητρα , "Mindarus", Εγκυκλοπαίδεια Μείζονος Ελληνισμού, Μ. Ασία URL: <http://www.ehw.gr/l.aspx?id=8209> Περίληψη : Spartan admiral of the Peloponnesian Fleet during 411- 410 B.C. He transferred the ships from Miletus to the Hellespont in order to ensure the cooperation of the satrap Pharnavazus and to hinder the Athenians’grain supply from the northern coast of the Black Sea. He was defeated near Cynossema followed by a defeat near Abydus. In the spring of 410 B.C. Mindarus suffered the ultimate defeat from Alcibiades during the Cyzicus naval battle when he was killed. Τόπος και Χρόνος Γέννησης 5th c. BC - Sparta Τόπος και Χρόνος Θανάτου 410 BC – Cyzicus Κύρια Ιδιότητα Admiral 1. Introduction Mindarus was an admiral of the Peloponnesian Fleet during the Ionian War in the period 411 – 419 B.C. The main sources of information with regard to his activity are ancient authors, mainly Thucydides, Xenophon and Diodorus and it is almost exclusively confined to his military activity in the area of the Hellespont. 2. Biography In 411 B.C. Mindarus succeeded Astyochus as admiral of the Peloponnesian Fleet in Miletus. Discontented however from satrap Tissaphernes’attitude who did not keep his promise to reinforce the Spartan fleet with Phoenician ships, he headed accompanied by 73 ships towards the Hellespont, with the intention of accepting the proposal of Pharnabazus, the Persian satrap of Daskyleion, to instigate a rebellion of the coastal cities under Athenian rule which formerly belonged to the satrapy of Pharnabazus. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} the Greco-Persian Wars by Peter Green Peter Green

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} The Greco-Persian Wars by Peter Green Peter Green. While The Greco-Persian Wars is a scholarly volume, with the full apparatus of notes and bibliography, it has the feel of more popular writing: one can sense Green's other calling as a historical novelist. So he uses anecdotes from later sources — Themistocles being warned by his father about the fickleness of the Athenian demos , the story about Aristeides and the ostrakon — without critical analysis and fills in gaps in the record with speculation and extrapolation. He indulges in comparisons with other periods, mostly with World War II — Themistocles is compared with Churchill and the medisers with Vichy. And we even get an old-fashioned touch of the "decided the fate of Europe" and "defence of freedom" themes. All of these things are guaranteed to arouse the ire of some; indeed the new introduction is mostly a response to criticisms levelled at The Year of Salamis . While Green does little more than hint at many factors (the differences in military technology, the importance of the Laurium silver strike, etc.), he offers something technical studies of such details or solid exegeses of Herodotus can not — an attempt to make sense of the wars as a whole, to provide a single coherent overview of them. There are surprisingly few works which attempt this and there are fewer still which combine a scholarly approach with popular accessibility. Green's accounts of the key battles are entrancing and the whole volume is hard to put down — for pure pleasure The Greco-Persian Wars is unmatched by anything I have read on the subject since I first discovered Mary Renault's Lion in the Gateway as a child.