Swamp Rabbit Trail Impact Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

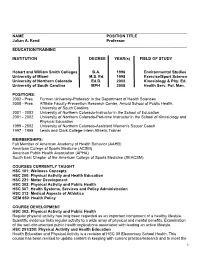

NAME POSITION TITLE Julian A. Reed Professor ______EDUCATION/TRAINING

________________________________________________________________________________ NAME POSITION TITLE Julian A. Reed Professor ________________________________________________________________________________ EDUCATION/TRAINING INSTITUTION DEGREE YEAR(s) FIELD OF STUDY Hobart and William Smith Colleges B.A. 1996 Environmental Studies University of Miami M.S. Ed. 1998 Exercise/Sport Science University of Northern Colorado Ed.D. 2002 Kinesiology & Phy. Ed. University of South Carolina MPH 2008 Health Serv. Pol. Man. POSITIONS: 2002 - Pres. Furman University-Professor in the Department of Health Sciences 2008 - Pres. Affiliate Faculty-Prevention Research Center, Arnold School of Public Health, University of South Carolina 2001 - 2002 University of Northern Colorado-Instructor in the School of Education 2001 - 2002 University of Northern Colorado-Part-time Instructor in the School of Kinesiology and Physical Education 1999 - 2002 University of Northern Colorado-Assistant Women’s Soccer Coach 1997 - 1998 Lewis and Clark College-Intern Athletic Trainer MEMBERSHIPS: Full Member of American Academy of Health Behavior (AAHB) American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) American Public Health Association (APHA) South East Chapter of the American College of Sports Medicine (SEACSM) COURSES CURRENTLY TAUGHT HSC 101: Wellness Concepts HSC 200: Physical Activity and Health Education HSC 221: Motor Development HSC 302: Physical Activity and Public Health HSC 307: Health Systems, Services and Policy Administration HSC 313: Medical Aspects of Athletics CEM 650: Health Policy COURSE DEVELOPMENT HSC 302: Physical Activity and Public Health Regular physical activity has long been regarded as an important component of a healthy lifestyle. Scientific evidence links regular activity to a wide array of physical and mental benefits. Examination of the well-documented public health implications associated with leading an active lifestyle. -

City Council Agenda

City Council Agenda Agenda Of 4-8-2019 Documents: AGENDA OF 4-8-2019.PDF Draft - Formal Minutes Of 3-25-2019 Documents: DRAFT - FORMAL MINUTES OF 3-25-2019.PDF Item 11a Documents: ITEM 11A - AGREEMENT - ACQUISITION OF LAND IN THE UNITY PARK AREA.PDF Item 11b Documents: ITEM 11B - CITY CODE - AMEND 19-3.2.2(O) RDV DISTRICT.PDF Item 11c Documents: ITEM 11C - Z-31-2018 - REZONE 801 GREEN AVENUE.PDF Item 11d Documents: ITEM 11D - Z-2-2019 - 2101 AUGUSTA STREET AND 18-20 EAST FARIS ROAD.PDF Item 11e Documents: ITEM 11E - AX-1-2019 - ANNEXATION - ROCKY SLOPE ROAD (REVISED).PDF Item 11f Documents: ITEM 11F - AGREEMENT - PERRY AVENUE INVESTORS, LLC FOR PUBLIC IMPROVEMENTS.PDF Item 11g Documents: ITEM 11G - AGREEMENT - CAP CAMPERDOWN, LLC FOR PUBLIC IMPROVEMENTS.PDF Item 15a Documents: ITEM 15A - AX-2-2019 - ANNEXATION - RIDGE STREET.PDF Item 15b Documents: ITEM 15B - APPROPRIATION 31,875,185 CAPITAL IMPROVEMENT PROGRAM.PDF Item 15c Documents: ITEM 15C - APPROPRIATION - 25,000 STEAM.PDF Item 15d Documents: ITEM 15D - APPROPRIATION - 251,000 ADDITIONAL FUNDING COMPREHENSIVE PLAN.PDF Item 16a Documents: ITEM 16A - AGREEMENT WITH THIRTEENTH CIRCUIT SOLICITORS OFFICE.PDF Questions on an agenda item? Contact Camilla Pitman, city clerk, at [email protected]. All media inquiries, please contact Leslie Fletcher, city public information officer, at [email protected] City Council Agenda Agenda Of 4-8-2019 Documents: AGENDA OF 4-8-2019.PDF Draft - Formal Minutes Of 3-25-2019 Documents: DRAFT - FORMAL MINUTES OF 3-25-2019.PDF Item 11a Documents: -

First Baptist Church | Greenville, SC

Mission Statement We are a community of believers in God as revealed in Jesus Christ as Lord. We believe in the authority of the Bible, the equality of all members, unity in diversity, and the priesthood of all believers. In communion with and through the power of the Holy Spirit, we follow the Way of Jesus the Christ and share the Good News through worship, education, ministries, and missions. As an autonomous Baptist Church, we value our heritage and the freedom it allows us to minister alongside other groups, both Christian andNews non-Christian. We express our love for all in gratitude for the love God has shown to us. January 27, 2014 First Baptist – Greenville 847 CLEVELAND STREET, GREENVILLE, SC 29601 864-233-2527 Frank The Wonder of Learning Comments... First Baptist’s Neighborhood Partnership with the Nicholtown Showdown at High Noon Community will take a giant step forward with the Make plans to attend the Man groundbreaking for construction vs. Machine contest this Saturday, The Reggio Children’s “The of Annie’s House, at 60 Baxter February 1, at noon on the front Wonder of Learning: The Street on Tuesday January 28 lawn of FBC-G. This event will Hundred Languages of Children” at 11:00 a.m. Due to weather raise money for those who need exhibit is in Greenville. Parents, concerns, the celebration will take help heating their homes. Ricky teachers and others volunteered place on the Terrace Level of the Power, Eric Coleman and Reggie their time to install the exhibit at AYMC. Rick Joye from Sustaining Cartee will use a hydraulic log McAlister Square. -

Revitalizing Greenville's West Side

Revitalizing Greenville’s West Side Overview At the turn of the 20th century, the west side of Greenville, South Carolina, was a thriving commercial district. However, as commercial activity shifted away from cotton, mills along the Reedy River struggled financially, and many Greenville residents left the city. The west side, home to 4,200 people (roughly seven percent of Greenville’s population), became increasingly abandoned or blighted, with derelict manufacturing buildings, textile facilities, and vacant and abandoned service stations.1 While a series of Federal, State, local, and private investments in Greenville’s west side neighborhoods in the late 1990s and early 2000s began to incrementally increase economic activity, improve housing, and generally create amenities and destinations throughout the neighborhoods, the projects were conducted in relative isolation. Building upon these individual project’s successes, the city is hoping to increase economic benefits by linking and coordinating development efforts. Key results of investment in the west side include: Developing Falls Park and the Liberty Bridge created a regional attraction on the west side and spurred local investment, including the nearby $65 million RiverPlace mixed‐use development; Gross business sales in the neighborhood increased from $243.8 million in 2000 to $401.2 million in 2008;2 The area has experienced a 300 percent increase in property tax revenue from 2002 through 2012;3 Construction of Fluor Field, a minor league baseball stadium, funded through a public-private partnership on a formerly contaminated site, has led to over $91.5 million in private development on the neighboring blocks,4 contributing to the 31 percent annual increase in property value in the West End since 2006;5 Redevelopment of several west side vacant or unused properties into productive facilities serving the community, including construction of the Salvation Army Ray and Joan Kroc Corps Community Center (Kroc Center) and the A.J. -

Greener Streets

Greenville’s Greener Streets A Compilation of Interdisciplinary Educational Programming Designed to Introduce Students to the Benefits of Trees in the Urban Environment Developed for Greenville, South Carolina By Livability Educator, Jaclin DuRant Greenville’s Greener Streets Program A compilation of educational programming related to trees in the urban environment developed by the Livability Educator for the City of Greenville. Though often overlooked, trees are an essential part of a healthy urban environment. Trees clean our water and air, cool our homes, help our streets last longer, provide habitats for animals, and much more. Helping students develop a familiarity with and an appreciation for the benefits that trees provide us will enhance their connection to the place where they live, and encourage them to protect and conserve trees. The lessons, information, and materials in this program have been compiled from the Urban Naturalist Program and the Community Quest Program, part of the Curriculum for Sustainability that was developed by the Livability Educator for the City of Greenville. This compilation was developed as part of a Green Streets Grant from TD Bank. Acknowledgments This program would not have been possible without the hard work and support of a number of individuals. I would especially like to thank Amanda Leblanc, A. J. Whittenberg Elementary School Librarian for her help in developing programming, her support, and her friendship, the Connections for Sustainability Project team; Wayne Leftwich and Christa Jordan, and the Green Streets Project team; Ginny Stroud, Sarah Cook, and Dale Westermeier for all of their help and support, Emily Hays for her fabulous attitude, helpful edits, and for her hard work developing the program glossary, and all of the teachers and community center staff who have allowed me to work with their students to create and test activities that would be effective and fun for many different age groups. -

Downtown Greenville

RUSSELL AVE W EARLE ST R D S K P To City of GARRAUX ST A W R To Travelers Rest Stone’s T A A Hampton T N E H Point V S B DUPONT DR A Colonel Elias Earle U Station E O RG P N D S E Historic District CARY ST M T O R T T IVY ST E S O W STONE AVE E EARLE ST E T For Downtown Trolley route F S H W V A T R T and schedule, go to: O CO E N S L E L H R www.greenvillesc.gov/597/trolley O I I S T MARSAILLES CT P D Z U ELIZABETH ST or download the B Westone V R L L T Greenville Trolley Tracker App at V E STONE AVE B D Main BENNETT ST N M JAY ST HARVLEY ST O yeahTHATtrolley.com NEAL ST T &Stone P M A H CABOT CT 276 DE WA E NORTH ST 183 VIOLA ST Hampton - Pinckney TOWNES ST T S A N MAIN ST L U Historic District E S Heritage H Amtrak WILTON ST East Park Avenue T VANNOY ST T S T I B ACCOMMODATIONS Station Historic District Historic District E N A N BRUCE ST L ROWLEY ST B S PINCKNEY ST A S D W PARK AVE M M R T 1 Aloft Greenville Downtown ECHOLS ST U BRIARCLIFF DR M H ITCH L POINSETT AVE AR ELL ST J MULBERRY ST C O OU T U 2 Courtyard by Marriott HAMPTON AVE ATWOOD ST R C S N T Overbrook I EN Y C TR DR P Greenville Downtown A R E M L Historic District RD LLOYD ST A AV E R ST K R E T O 3 Embassy Suites by Hilton SH E A M O ASBURY AVE LL E T R Greenville Downtown RiverPlace 15 C S B A B VE 123 R 12 T R W WASHINGTON ST P E PARK AVE RAILROAD ST E O U V 4 Hampton Inn & Suites Greenville T O N O S K 10 MCPHERSON L S FERN ST DowntownE @ RiverPlace B 11 CENTER ST A I L PARK N CHURCH ST W S D O R HILLY ST E IG R C G B 5C HolidayE Inn AExpress & ON V K S 3 SUNFLOWER -

Stronger Economies Through Active Communities the Economic Impact of Walkable, Bikeable Communities in South Carolina Acknowledgements

Stronger Economies through Active Communities The Economic Impact of Walkable, Bikeable Communities in South Carolina Acknowledgements This report was written by Lauren Wright and Hannah Jones Walters with Eat Smart Move More South Carolina (ESMMSC). A special thank you is extended to Amy Johnson Ely with the Palmetto Cycling Coalition for her valuable guidance and feedback. The development of this report was supported through the Let’s Go! SC initiative, funded by the BlueCross BlueShield of South Carolina Foundation, an independent licensee of the Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association. ESMMSC would also like to acknowledge the many individuals listed below who shared their stories, expertise, and guidance, without which this report would not be possible. Larry Bagwell Drew Griffin Amanda Pope City of Easley City of Florence City of Florence Tom Bell Adrienne Hawkins Laura Ringo City of Rock Hill Travelers Rest Farmers’ Market Partners for Active Living Brandy Blumrich-Sellingworth Laurie Helms Will Rothschild Retrofit Sip-n-Serve City of Rock Hill City of Spartanburg Susan Collier Kelly Kavanaugh Blake Sanders SC Department of Health & SC Department of Health & Alta Planning + Design Environmental Control Environmental Control Dr. Mark Senn Lindsay Cunningham Matt Kennell Beaufort Memorial Hospital City of Easley City Center Partnership Jonathan Sherwood Dr. William J. Davis Erika Kirby Lowcountry Council of Governments The Citadel BlueCross BlueShield of SC Philip Slayter Leigh DeForth Foundation Colleton County City of Columbia Alta -

Ryan Harper LAND of Make Believe

Ryan Harper LAND OF MAKE BELIEVE It is the Emerald City. Scroll through any online list of “top small cities” in the United States, and you’ll likely find Greenville, South Carolina. Talk to citizens who have lived in the city for ten to thirty years, and they will tell you why. So the story goes, when the decline of the South Carolina textile indus- try began, a handful of local businessmen and government officials led Green- ville through a decades-spanning strategic revitalization project. Michelin and BMW moved their major operations into the Greenville area in the late 1970s and 1980s. Hotels and banks set up shop in the city’s downtown—a down- town which Max Heller, a World War II-era Austrian Jewish immigrant who served as Greenville’s mayor in the 1970s, helped to beautify. The Swamp Rab- bit Trail, which replaced a rail line left over from the Carolina textile industry’s heyday, was completed in 2010 and still is being extended today. This paved, multiuse path runs through the heart of the downtown—notably, through the downtown’s lovely Falls Park, where nearly year-round visitors and residents walk and bike along the Reedy River as it rolls down from the high places. Waterfalls exist all over this region of South Carolina, which is called the Up- state, largely due to the Blue Ridge Escarpment north of town, where the land precipitously drops 2,000 feet—or rises, depending on your orientation. The road that used to run above the downtown falls has given way to the stunning Liberty Bridge, a curved pedestrian suspension bridge completed in 2004. -

FY 2017-2018 Adopted Budget

Annual Operating Budget Fiscal Year 2017 - 2018 Prepared by the City of Greenville Office of Management and Budget ADOPTED This page intentionally left blank. City of Greenville, South Carolina Annual Operating Budget Fiscal Year July 1, 2017 through June 30, 2018 Knox H. White Mayor Amy Ryberg Doyle Lillian Brock Flemming Council Member (District 1) Council Member (District 2) Jil M. Littlejohn J. David Sudduth Council Member (District 3) Council Member (District 4) George Fletcher Gaye G. Sprague Council Member (At Large) Council Member (At Large) John F. Castile City Manager Matthew Hawley Michael Pitts Municipal Judge (Appointee) City Attorney (Appointee) Nancy Whitworth Camilla Pittman Deputy City Manager/Economic Development Director City Clerk Athena Miller Kenneth Miller Human Resources Director Chief of Police Angela Prosser Stephen Kovalcik Public Information & Events Director Fire Chief Mike Murphy Mari Steinbach Public Works Director Parks & Recreation Director Gary Shepard Kai Nelson Public Transportation Director Office of Management and Budget Director Budget Staff Matt Efird Kristina Junker Tammy Seel Budget Administrator Budget Analyst/Auditor Budget & Management Analyst The Government Finance Officers Association of the United States and Canada (GFOA) presented a Distinguished Budget Presentation Award to the City of Greenville, South Carolina for its annual budget for the fiscal year beginning July 1, 2016. In order to receive this award, a governmental unit must publish a budget document that meets program criteria as a policy document, as an operations guide, as a financial plan, and as a communications device. The award is valid for a period of one year only. We believe our current budget continues to conform to program requirements, and we are submitting it to GFOA to determine its eligibility for another award. -

Long Range Facilities Plan and Capital Improvement Program

Greenville County Schools Board Members Dr. Crystal Ball O'Connor, Chair (Area 27) Debi C. Bush, Vice Chair (Area 19) Joy Grayson (Area 17) Patrick L. Sudduth (Area 18) Charles J. "Chuck" Saylors (Area 20) Danna Rohleder (Area 21) Lynda Leventis-Wells, Secretary (Area 22) Glenda Morrison-Fair (Area 23) Derek Lewis (Area 24) Michelle Goodwin-Calwile (Area 25) Roger D. Meek (Area 26) Lisa H. Wells (Area 28) Dr. Burke Royster, Superintendent Dr. Mason Gary, Deputy Superintendent Betty Farley Executive Director for Planning and Demographics Mission: We collaborate with the home and community to provide educational experiences which prepare students for life-long learning and for ethical, productive participation in a democratic society and the global community. Vision: To be an exemplary, continuously improving educational organization in which all students achieve their maximum potential through a rigorous, engaging curriculum and support systems that cultivate and promote their well-being. Goal 3: Provide a School Environment Supportive of Learning Table of Contents Greenville County Schools FY 2019 - 2023 Long Range Facilities Plan and Capital Improvement Program , I. Overview. .... .. ......................................................................................... .................... II. CIP Summary...................................................................................................... ..... ... II Ill. Chapter 1 - Greenville County Schools Planning Environment.. .... ......................... ......... ... . -

Do Wnt O Wn Greenville

Colonel Elias Earle Historic District W STONE AVE For Downtown Trolley route and schedule, go to: www.greenvillesc.gov/597/trolley D LV or download the Greenville Trolley Tracker App E STONE AVE B N O T P M A H DE WA Hampton - Pinckney Heritage Amtrak Station Historic District Historic District ACCOMMODATIONS W PARK AVE East Park Avenue 11 Aloft Greenville Downtown Historic District Overbrook Historic District 2 Courtyard by Marriott Greenville Downtown 9 3 Embassy Suites by Hilton 7 P E PARK AVE Greenville Downtown RiverPlace 5 MCPHERSON 6 PARK 4 Hampton Inn & Suites Greenville 3 Downtown @ RiverPlace 8 W BROAD ST COLLEGE ST 5 Holiday Inn Express & G W ELFORD ST H Suites Downtown Greenville S BUNCOMBE ST 5 S w Reedy River a 6 Home2 Suites by Hilton m 6 p N ACADEMY ST R Greenville Downtown a b b E ELFORD ST i 6 t T 1 7 Homewood Suites by Hilton r a i Peace l Downtown Greenville T TD Center S Stage 10 N 9 P 8 Hyatt Place Greenville Downtown O P Swamp Rabbit S Bon Secours D P Splash Track W NORTH ST Wellness Arena Hyatt Regency Greenville R NOMA 9 LAURENS ST B E Wyche A Square A T H T Pavilion S MAIN ST I P C P E 108 Residence Inn by Marriott I T P E NORTH ST L R S W Greenville Downtown G W A N S I H ONE N MAIN ST E NORTH ST Eugenia I R N Brown Street G P P 11 Springhill Suites by Marriott Duke T City Art Crossing O S N Bridgebridge S Plaza N at RiverPlace T ST 1 E COFFEE ST H Greenville Downtown ORT E N Kroc W MCBEE AVE 12 The Westin Poinsett Greenville MAYBERRY Tennis P E WASHINGTON ST N CHURCH ST Pettigru PARK Center Bus POINTS OF INTEREST Station Historic District W 10 1 1 Liberty Bridge The Children’s Garden B P 11 P R 2 @ Linky Stone Park G Reedy River O T 22 Falls Park on the Reedy H A S S W COURT ST Sw D am G p S 12 N T I 33 Fluor Field at the West End Ra bb R it P P Tr S ail E MCBEE AVE 64 Greenville Zoo E COURT ST S T S E WASHINGTON ST 2 75 Carolina Music Museum R Visitor E V P 4 Center R S ACADEMY ST I Peace ZOO 4 D 56 Greenville Co. -

Adopted Capital Improvements Program FY 2016

Capital Improvement Program FISCAL YEARS 2016 - 2019 ADOPTEDPrepared by the City of Greenville Offi ce of Management and Budget City of Greenville, South Carolina Adopted Capital Improvement Program FY 2016-2019 Knox H. White Mayor Amy Ryberg Doyle Council Member (District 1) Lillian Brock Flemming Council Member (District 2) Jil M. Littlejohn Council Member (District 3) J. David Sudduth Council Member (District 4) Susan Reynolds Council Member (At Large) Gaye G. Sprague Council Member (At Large) John F. Castile City Manager FY 2016-2019 CIP City of Greenville, South Carolina Table of Contents FY 2016-2019 CIP City of Greenville, South Carolina City of Greenville, South Carolina FY 2016-2019 Adopted Capital Improvement Program Table of Contents Transmittal ........................................................................................................................ A-1 Transmittal Letter ................................................................................................................ A-3 Summary Schedules ............................................................................................................. B-1 Schedule I – Total CIP Revenue and Expenditure Summary ............................................................... B-3 Schedule II – Project Summaries with Applicable Funding Sources ...................................................... B-4 Schedule III – Project Summaries by Funding Source ...................................................................... B-11 Project Descriptions Roads and