Revitalizing Greenville's West Side

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

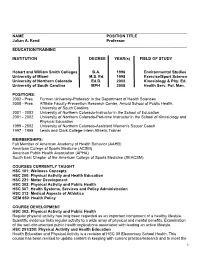

NAME POSITION TITLE Julian A. Reed Professor ______EDUCATION/TRAINING

________________________________________________________________________________ NAME POSITION TITLE Julian A. Reed Professor ________________________________________________________________________________ EDUCATION/TRAINING INSTITUTION DEGREE YEAR(s) FIELD OF STUDY Hobart and William Smith Colleges B.A. 1996 Environmental Studies University of Miami M.S. Ed. 1998 Exercise/Sport Science University of Northern Colorado Ed.D. 2002 Kinesiology & Phy. Ed. University of South Carolina MPH 2008 Health Serv. Pol. Man. POSITIONS: 2002 - Pres. Furman University-Professor in the Department of Health Sciences 2008 - Pres. Affiliate Faculty-Prevention Research Center, Arnold School of Public Health, University of South Carolina 2001 - 2002 University of Northern Colorado-Instructor in the School of Education 2001 - 2002 University of Northern Colorado-Part-time Instructor in the School of Kinesiology and Physical Education 1999 - 2002 University of Northern Colorado-Assistant Women’s Soccer Coach 1997 - 1998 Lewis and Clark College-Intern Athletic Trainer MEMBERSHIPS: Full Member of American Academy of Health Behavior (AAHB) American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) American Public Health Association (APHA) South East Chapter of the American College of Sports Medicine (SEACSM) COURSES CURRENTLY TAUGHT HSC 101: Wellness Concepts HSC 200: Physical Activity and Health Education HSC 221: Motor Development HSC 302: Physical Activity and Public Health HSC 307: Health Systems, Services and Policy Administration HSC 313: Medical Aspects of Athletics CEM 650: Health Policy COURSE DEVELOPMENT HSC 302: Physical Activity and Public Health Regular physical activity has long been regarded as an important component of a healthy lifestyle. Scientific evidence links regular activity to a wide array of physical and mental benefits. Examination of the well-documented public health implications associated with leading an active lifestyle. -

City Council Agenda

City Council Agenda Agenda Of 4-8-2019 Documents: AGENDA OF 4-8-2019.PDF Draft - Formal Minutes Of 3-25-2019 Documents: DRAFT - FORMAL MINUTES OF 3-25-2019.PDF Item 11a Documents: ITEM 11A - AGREEMENT - ACQUISITION OF LAND IN THE UNITY PARK AREA.PDF Item 11b Documents: ITEM 11B - CITY CODE - AMEND 19-3.2.2(O) RDV DISTRICT.PDF Item 11c Documents: ITEM 11C - Z-31-2018 - REZONE 801 GREEN AVENUE.PDF Item 11d Documents: ITEM 11D - Z-2-2019 - 2101 AUGUSTA STREET AND 18-20 EAST FARIS ROAD.PDF Item 11e Documents: ITEM 11E - AX-1-2019 - ANNEXATION - ROCKY SLOPE ROAD (REVISED).PDF Item 11f Documents: ITEM 11F - AGREEMENT - PERRY AVENUE INVESTORS, LLC FOR PUBLIC IMPROVEMENTS.PDF Item 11g Documents: ITEM 11G - AGREEMENT - CAP CAMPERDOWN, LLC FOR PUBLIC IMPROVEMENTS.PDF Item 15a Documents: ITEM 15A - AX-2-2019 - ANNEXATION - RIDGE STREET.PDF Item 15b Documents: ITEM 15B - APPROPRIATION 31,875,185 CAPITAL IMPROVEMENT PROGRAM.PDF Item 15c Documents: ITEM 15C - APPROPRIATION - 25,000 STEAM.PDF Item 15d Documents: ITEM 15D - APPROPRIATION - 251,000 ADDITIONAL FUNDING COMPREHENSIVE PLAN.PDF Item 16a Documents: ITEM 16A - AGREEMENT WITH THIRTEENTH CIRCUIT SOLICITORS OFFICE.PDF Questions on an agenda item? Contact Camilla Pitman, city clerk, at [email protected]. All media inquiries, please contact Leslie Fletcher, city public information officer, at [email protected] City Council Agenda Agenda Of 4-8-2019 Documents: AGENDA OF 4-8-2019.PDF Draft - Formal Minutes Of 3-25-2019 Documents: DRAFT - FORMAL MINUTES OF 3-25-2019.PDF Item 11a Documents: -

Falls Park on the Reedy

SCNLA Garden Profile: Falls Park on the Reedy By Ellen Vincent, Clemson University Environmental Landscape Specialist There is a place in South Carolina where children, has two 90 foot tall masts that weigh waterfall below. The bridge may sound like natural and built features merge with one over 28 tons each and lean at an appealing 15° a futuristic air ship, but the curves, angles, another; where architectural form and angle. Cables hold the masts in position while and lightness all seem perfectly natural and function blend; and beauty, art, culture, and steel piles and rock anchors plunge 70 feet approachable in this setting, floating above commerce harmoniously co-exist. Welcome deep into bedrock to transfer the bridge loads the waterfalls and gardens with the skyline to the Falls River Park on the Reedy in to the ground. The bridge is 345 feet long, 12 of Greenville clearly in view. historic West End, downtown Greenville. feet wide, and 8” thick. The deck is made of reinforced concrete and has a delightful curve Two other works of art in Falls River Park Background that is intentionally cantilevered toward the include the untitled piece by Joel Shapiro and Falls Park on the Reedy is a public park, owned and operated by the City of Greenville. The site was rather decrepit and people avoided it before 1965. A City of Greenville press release from 2004 described the space in the mid 1900s as in a severe decline. “The water was polluted and the grounds were littered with river debris and trash.” Adding further insult to the scene was the construction of the Camperdown Bridge which blocked views and access. -

54Th ANNUAL CONVENTION June 26 - 28, 2019

54th ANNUAL CONVENTION June 26 - 28, 2019 220 N Main Street Greenville, SC Tentative Schedule Wednesday, June 26 Thursday, June 27 (cont’d) 1:00 - 6:00 pm Registration 9:00 - 11:30 am General Session (cont’d) 3:00 - 3:30 pm Associate Members Meeting Denise Ryan, MBA, CSP 3:45 - 5:30 pm Opening Session followed by the Fire Star Speaking - How to Communicate with Board of Directors Meeting Everyone Who Isn’t You OPEN TO ALL Sam Pierce, MSHA All are encouraged to attend MSHA SE District Update Including spouses & guests 11:30 am - 12:30 pm Lunch Buffet - Non-Golfers 12:30 pm Golf Tournament The Preserve at Verdae Randy Weingart, NSSGA Transportation will be provided Aggregate Research - Shot Gun Start Then and Now - A Thirty Year Perspective 12:30 - 3:30 pm Scavenger Hunt Cards must be turned in by 3:30 pm Drawing for the $250 Grand Prize will be Awarded at the Friday Celebration Breakfast 5:30 - 6:30 pm Hospitality Suite 12:30 - 5:30 pm Free Time for non-golfers 6:30 - 7:30 pm Welcome Reception 5:30 - 7:00 pm Hospitality Suite NOTE CHANGE: with Heavy hors d’oeuvres 7:30 - 10:00 pm NCAA DINNER WILL BE NOTE CHANGE: TONIGHT in the Hyatt DINNER ON YOUR OWN - 10:00 -11:59 pm Hospitality Suite This is the night to take clients to dinner Thursday, June 27 To enjoy the sights and sounds 7:30 am - 12:00 pm Registration of Greenville, SC 6:00 - 11:00 am Breakfast Buffet - Roost The Band Whitehall will be (864) 298-2424 playing on the NOMA outside the Tickets will be in the Hyatt from 5:30 - 8:30 pm registration packets for you to 10:00 - 11:59 pm Hospitality Suite eat at your leisure in the Roost Restaurant Friday, June 28 9:00 - 11:30 am General Session 8:00 - 10:30 am Celebration Breakfast Gary J. -

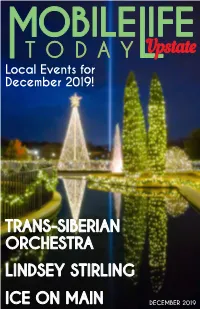

Mobilelife Today

T O D A Y Local Events for December 2019! TRANS-SIBERIAN ORCHESTRA LINDSEY STIRLING ICE ON MAIN DECEMBER 2019 CONTENTS LOCAL EVENTS Arts & Cultural Events 2-3 5 Concerts 3-4 Food Events 4 Festivals & Fairs 5-6 Sports 6 Other Events 7 New Year’s Eve Events 7-8 Recurring Events 9 6 ACTIVITIES FOR KIDS Just for Fun 10-11 SPEEDWAY Drop-Off Events 11 CHRISTMAS DAY TRIPS 12 PUBLISHER David Nichols 12 EDITOR Katie Nichols DESIGNER Kelly Vervaet COVER PHOTO Derek Eckenroth Bob Jones University Christmas Lights 5 LINDSEY Sales and freelance writer opportunities are STIRLING available. Send inquiries to: [email protected] If you would like your business featured in MobileLife Today Upstate, 4 please contact us at: [email protected] If you would like your event featured, please contact: [email protected] Comments and suggestions are always 3 welcome at: ©2019, All Rights Reserved [email protected] Reproduction without permission is prohibited MobileLife Today is published by 1 upstate.mobilelifetoday.com ModernLife publishing LOCAL EVENTS Arts & Cultural Events ArtBreak: Illuminations A Holly Jolly Christmas Date/Time: Dec. 12th, 12pm Date/Time: Dec. 5th-21st, Various Times Location: Applied Studies Building Location: Centre Stage Bob Jones University Cost: $23.50-$36.50 Cost: $10 for lunch and lecture Description: “Have a cup of cheer” and cel- Description: Let there be light—a single ebrate the holiday season with a hilarious phrase, an unleashed beauty. By light’s illu- and heartwarming Christmas variety show mination we discern all the colors, contours, perfect for the entire family! Featuring your shapes, forms, and textures of our world. -

City Guide Greenville, SC Moving to Greenville

City Guide Greenville, SC Where to Live 2 Moving to Greenville - What You Museums 3 Historical Sites 3 Theaters & Music Venues 4 Need to Know Dining 5 Shopping 5 So you’re moving to the Greenville area? Well, get excited because there is no shortage of amazing things to see, do and eat in the Upstate (called that for being Outdoor Recreation 6 part of the “upper” region of the state)! Regardless of what your interests are, Seasonal Events 6 you’re in for a fun-filled next chapter of your life! hilldrup.com 800.476.6683 Moving to Greenville, SC Where to Live First things first, where to live? Greenville has a diverse set of maintenance, downtown modern condos are also available and neighborhoods that can accommodate just about any pace – give empty nesters all the benefits of city living. and stage – of life. Empty nesters may want to consider homes in these Millennials neighborhoods: Greenville is the jewel of South Carolina’s Upstate region. Nestled in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains, a good hike is just minutes • Pebble Creek away and wonderful beaches and the historic city of Charleston • Riverplace are just a few hours further. Right in Greenville, there’s plenty of • Woodlands at Furman shopping, food and entertainment to keep you busy! It’s easy to see • The Cottages why so many young professionals opt to live here. • Swansgate • Sugar Creek Villas Greenville’s housing market attracts both homeowners and renters alike, and popular neighborhoods and subdivisions for millennials include the following: • Verdae • Arcadia • Cobblestone • West End • Overbrook • McBee Stations Young Families Greenville is a wonderful place for young families to flourish, with a lifestyle at a slightly slower pace compared to larger cities. -

Downtown Greenville Master Plan Greenville, South Carolina

Downtown Greenville Master Plan Greenville, South Carolina June 2008 Sasaki Associates, Inc. W-ZHA CGD Table of Contents Executive Summary 1 Greenville Today 11 Positioning Greenville 17 Master Planning Principles 27 Five Corners 33 Making Connections 47 Implementation Strategy 59 Acknowledgments 84 Executive Summary 01 CHAPTERCHAPTER Executive Summary The City of Greenville has undertaken this current master plan as a way to look forward and ensure the success of downtown for the next twenty years. In each decade, Greenville has stepped ahead of other cities, acting boldly to reinvent and strengthen the downtown. This proactive approach has served the City well, making Greenville a model for other cities to emulate. As the City well realizes, the work of building and sustaining downtowns is an ongoing endeavor. In this light, the City of Greenville has undertaken this current master plan as a way to look forward and ensure the success of downtown for the next twenty years. The plan faces the realities of downtown today, building on its strengths and confronting issues Figure 1.1. The downtown Greenville Skyline. that must be addressed to move forward. The goals of this master plan are to: . Create a framework for future development downtown . Reinforce the role of downtown as an economic catalyst for the region . Leverage prior successes to move to the next level 4. Create a fully functional mixed use, sustainable, urban environment. Main Street is understood to be the center of downtown but the definition of the outer boundaries varies, especially as Main Street has been extended (Figure .). For the purposes of this study, the downtown area is defined by the Stone Avenue corridor on the north, the Butler Street Corridor on the west, the Church Street corridor on the east and University Ridge and the Stadium on the south. -

First Baptist Church | Greenville, SC

Mission Statement We are a community of believers in God as revealed in Jesus Christ as Lord. We believe in the authority of the Bible, the equality of all members, unity in diversity, and the priesthood of all believers. In communion with and through the power of the Holy Spirit, we follow the Way of Jesus the Christ and share the Good News through worship, education, ministries, and missions. As an autonomous Baptist Church, we value our heritage and the freedom it allows us to minister alongside other groups, both Christian andNews non-Christian. We express our love for all in gratitude for the love God has shown to us. January 27, 2014 First Baptist – Greenville 847 CLEVELAND STREET, GREENVILLE, SC 29601 864-233-2527 Frank The Wonder of Learning Comments... First Baptist’s Neighborhood Partnership with the Nicholtown Showdown at High Noon Community will take a giant step forward with the Make plans to attend the Man groundbreaking for construction vs. Machine contest this Saturday, The Reggio Children’s “The of Annie’s House, at 60 Baxter February 1, at noon on the front Wonder of Learning: The Street on Tuesday January 28 lawn of FBC-G. This event will Hundred Languages of Children” at 11:00 a.m. Due to weather raise money for those who need exhibit is in Greenville. Parents, concerns, the celebration will take help heating their homes. Ricky teachers and others volunteered place on the Terrace Level of the Power, Eric Coleman and Reggie their time to install the exhibit at AYMC. Rick Joye from Sustaining Cartee will use a hydraulic log McAlister Square. -

Greener Streets

Greenville’s Greener Streets A Compilation of Interdisciplinary Educational Programming Designed to Introduce Students to the Benefits of Trees in the Urban Environment Developed for Greenville, South Carolina By Livability Educator, Jaclin DuRant Greenville’s Greener Streets Program A compilation of educational programming related to trees in the urban environment developed by the Livability Educator for the City of Greenville. Though often overlooked, trees are an essential part of a healthy urban environment. Trees clean our water and air, cool our homes, help our streets last longer, provide habitats for animals, and much more. Helping students develop a familiarity with and an appreciation for the benefits that trees provide us will enhance their connection to the place where they live, and encourage them to protect and conserve trees. The lessons, information, and materials in this program have been compiled from the Urban Naturalist Program and the Community Quest Program, part of the Curriculum for Sustainability that was developed by the Livability Educator for the City of Greenville. This compilation was developed as part of a Green Streets Grant from TD Bank. Acknowledgments This program would not have been possible without the hard work and support of a number of individuals. I would especially like to thank Amanda Leblanc, A. J. Whittenberg Elementary School Librarian for her help in developing programming, her support, and her friendship, the Connections for Sustainability Project team; Wayne Leftwich and Christa Jordan, and the Green Streets Project team; Ginny Stroud, Sarah Cook, and Dale Westermeier for all of their help and support, Emily Hays for her fabulous attitude, helpful edits, and for her hard work developing the program glossary, and all of the teachers and community center staff who have allowed me to work with their students to create and test activities that would be effective and fun for many different age groups. -

Downtown Greenville

RUSSELL AVE W EARLE ST R D S K P To City of GARRAUX ST A W R To Travelers Rest Stone’s T A A Hampton T N E H Point V S B DUPONT DR A Colonel Elias Earle U Station E O RG P N D S E Historic District CARY ST M T O R T T IVY ST E S O W STONE AVE E EARLE ST E T For Downtown Trolley route F S H W V A T R T and schedule, go to: O CO E N S L E L H R www.greenvillesc.gov/597/trolley O I I S T MARSAILLES CT P D Z U ELIZABETH ST or download the B Westone V R L L T Greenville Trolley Tracker App at V E STONE AVE B D Main BENNETT ST N M JAY ST HARVLEY ST O yeahTHATtrolley.com NEAL ST T &Stone P M A H CABOT CT 276 DE WA E NORTH ST 183 VIOLA ST Hampton - Pinckney TOWNES ST T S A N MAIN ST L U Historic District E S Heritage H Amtrak WILTON ST East Park Avenue T VANNOY ST T S T I B ACCOMMODATIONS Station Historic District Historic District E N A N BRUCE ST L ROWLEY ST B S PINCKNEY ST A S D W PARK AVE M M R T 1 Aloft Greenville Downtown ECHOLS ST U BRIARCLIFF DR M H ITCH L POINSETT AVE AR ELL ST J MULBERRY ST C O OU T U 2 Courtyard by Marriott HAMPTON AVE ATWOOD ST R C S N T Overbrook I EN Y C TR DR P Greenville Downtown A R E M L Historic District RD LLOYD ST A AV E R ST K R E T O 3 Embassy Suites by Hilton SH E A M O ASBURY AVE LL E T R Greenville Downtown RiverPlace 15 C S B A B VE 123 R 12 T R W WASHINGTON ST P E PARK AVE RAILROAD ST E O U V 4 Hampton Inn & Suites Greenville T O N O S K 10 MCPHERSON L S FERN ST DowntownE @ RiverPlace B 11 CENTER ST A I L PARK N CHURCH ST W S D O R HILLY ST E IG R C G B 5C HolidayE Inn AExpress & ON V K S 3 SUNFLOWER -

THAT's the Spot

THAT’s the spot AMERICAN THE ANCHORAGE This eclectic neighborhood restaurant located in the Village of West Greenville specializes in expertly crafted small plates, esoteric wines, and craft cocktails. •586 Perry Ave.; 864.219.3082; EAT & DRINK theanchoragerestaurant.com; $$ D ARTISAN Pecan-crusted trout and shrimp and grits number among the tempting items on the menu of the dining room at the Greenville Marriott. • One Parkway East; 864.297.0300; artisangreenville.com; $$ AUGUSTA GRILL The menu changes daily at this neigh- borhood eatery, a go-to on Augusta for more than 20 years. Locals in the know drop in on Wednesday nights for the crab cake special. •1818 Augusta St., Suite 116; 864.242.0316; augustagrill.com; $$$ D BISTRO 45 CAROLINA FRESH Focusing on fresh regional products from SC growers and producers, the Hilton Green- ville’s restaurant menu highlights the likes of cedar-roasted salmon and a flame-roasted bone-in pork chop. • 45 W. Orchard Park Dr.; $$ Devils Fork State Park 864.232.4747; greenvillesc.hilton.com; CALIFORNIA DREAMING RESTAURANT For generous portions, reasonable prices, and fresh American cuisine head to California Dreaming for a laid-back night out. Entrées range from baby back ribs to fresh seafood and pasta. • 40 Beacon Dr.; 864.234.9000; californiadreaming.rest/location/greenville-sc; $$ CAROLINA ALE HOUSE American favorites on the menu, 20 TV screens, and a rooftop bar make Carolina Ale House a family-friendly place to enjoy a burger while you root for your favorite team. • 113 S. Main St.; 864.351.0521; carolinaalehouse.com; $$ Order a guide at SouthCarolinaParks.com or pick one up at any state park, and collect a stamp at each park you visit to start your CRAFT 670 RESTAURANT & BAR journey toward becoming an Ultimate Outsider. -

Stronger Economies Through Active Communities the Economic Impact of Walkable, Bikeable Communities in South Carolina Acknowledgements

Stronger Economies through Active Communities The Economic Impact of Walkable, Bikeable Communities in South Carolina Acknowledgements This report was written by Lauren Wright and Hannah Jones Walters with Eat Smart Move More South Carolina (ESMMSC). A special thank you is extended to Amy Johnson Ely with the Palmetto Cycling Coalition for her valuable guidance and feedback. The development of this report was supported through the Let’s Go! SC initiative, funded by the BlueCross BlueShield of South Carolina Foundation, an independent licensee of the Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association. ESMMSC would also like to acknowledge the many individuals listed below who shared their stories, expertise, and guidance, without which this report would not be possible. Larry Bagwell Drew Griffin Amanda Pope City of Easley City of Florence City of Florence Tom Bell Adrienne Hawkins Laura Ringo City of Rock Hill Travelers Rest Farmers’ Market Partners for Active Living Brandy Blumrich-Sellingworth Laurie Helms Will Rothschild Retrofit Sip-n-Serve City of Rock Hill City of Spartanburg Susan Collier Kelly Kavanaugh Blake Sanders SC Department of Health & SC Department of Health & Alta Planning + Design Environmental Control Environmental Control Dr. Mark Senn Lindsay Cunningham Matt Kennell Beaufort Memorial Hospital City of Easley City Center Partnership Jonathan Sherwood Dr. William J. Davis Erika Kirby Lowcountry Council of Governments The Citadel BlueCross BlueShield of SC Philip Slayter Leigh DeForth Foundation Colleton County City of Columbia Alta