Sin Sheep and Scotsmen John George Adair And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KEEPING an EYE on YOUGHAL: the Freeman's Journal and The

KEEPING AN EYE ON YOUGHAL: The Freeman’s Journal and the Plan of Campaign in East Cork, 1886–92 Felix M. Larkin THE SKIBBEREEN EAGLE FAMOUSLY declared in that it would be keeping an eye on the Tsar of Russia (Potter, : , –). A decade or so earlier, Youghal was very much in the eye of the press – and, indeed, in the eye of the storm – during the Plan of Campaign, the second phase of the Land War in Ireland. The tenants on the nearby Ponsonby estate were the first to adopt the Plan of Cam- paign in November in order to secure lower rents (Donnelly, : , – ). The struggle that ensued dragged on inconclusively until it was overtaken by the Parnell spilt in the s, and the Ponsonby tenants – like so many others else- where in the country – were then left high and dry, with no alternative but to settle on terms that fell far short of what they sought (Geary, : ). The Freeman’s Journal was the main nationalist daily newspaper in Ireland at that time, and it kept its eye closely on developments in and around Youghal as it covered the Plan of Campaign throughout the country – often in remarkable detail. What I want to do in this paper is briefly to outline the Freeman’s coverage of the events in Youghal, and to place its coverage of those events in the wider context of Irish political jour- nalism in the second half of the nineteenth century. In , when the Plan of Campaign began, the Freeman’s Journal was the prop- erty of Edmund Dwyer Gray MP – who had inherited the newspaper on the death of his father, Sir John Gray, in .Italreadyhadalongandchequeredhistory, having been founded in Dublin in to support the ‘patriot’ opposition in the Irish parliament in College Green. -

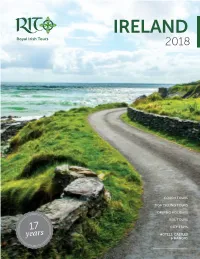

2018 CELEBRATING 17 Years

2018 CELEBRATING 17 years Canadian The authentic Irish roots One name, Company, Irish experience, run deep four spectacular Irish Heritage created with care. at RIT. destinations. Welcome to our We can recommend Though Canada is As we open tours 17th year of making our tours to you home for the Duffy to new regions memories in Ireland because we’ve family, Ireland is of the British Isles with you. experienced in our blood. This and beyond, our It’s been our genuine them ourselves. patriotic love is the priority is that we pleasure to invite you We’ve explored the driving force behind don’t forget where to experience Ireland magnificent basalt everything we do. we came from. up close and personal, columns at the We pride ourselves For this reason, and we’re proud Giant’s Causeway and on the unparalleled, we’ve rolled all of the part we’ve breathed the coastal personal experiences of our tours in played in helping to air at the mighty that we make possible under the name create thousands of Cliffs of Moher. through our strong of RIT. Under this exceptional vacations. We’ve experienced familiarity with the banner, we are As our business has the warm, inviting land and its locals. proud to present grown during this atmosphere of a The care we have for you with your 2018 time, the fundamental Dublin pub and Ireland will be evident vacation options. purpose of RIT has immersed ourselves throughout every Happy travels! remained the same: to in the rich mythology detail of your tour. -

Behind the Scenes

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd 689 Behind the Scenes SEND US YOUR FEEDBACK We love to hear from travellers – your comments keep us on our toes and help make our books better. Our well-travelled team reads every word on what you loved or loathed about this book. Although we cannot reply individually to your submissions, we always guarantee that your feedback goes straight to the appropriate authors, in time for the next edition. Each person who sends us information is thanked in the next edition – the most useful submissions are rewarded with a selection of digital PDF chapters. Visit lonelyplanet.com/contact to submit your updates and suggestions or to ask for help. Our award-winning website also features inspirational travel stories, news and discussions. Note: We may edit, reproduce and incorporate your comments in Lonely Planet products such as guidebooks, websites and digital products, so let us know if you don’t want your comments reproduced or your name acknowledged. For a copy of our privacy policy visit lonelyplanet.com/ privacy. Anthony Sheehy, Mike at the Hunt Museum, OUR READERS Steve Whitfield, Stevie Winder, Ann in Galway, Many thanks to the travellers who used the anonymous farmer who pointed the way to the last edition and wrote to us with help- Knockgraffon Motte and all the truly delightful ful hints, useful advice and interesting people I met on the road who brought sunshine anecdotes: to the wettest of Irish days. Thanks also, as A Andrzej Januszewski, Annelise Bak C Chris always, to Daisy, Tim and Emma. Keegan, Colin Saunderson, Courtney Shucker D Denis O’Sullivan J Jack Clancy, Jacob Catherine Le Nevez Harris, Jane Barrett, Joe O’Brien, John Devitt, Sláinte first and foremost to Julian, and to Joyce Taylor, Juliette Tirard-Collet K Karen all of the locals, fellow travellers and tourism Boss, Katrin Riegelnegg L Laura Teece, Lavin professionals en route for insights, information Graviss, Luc Tétreault M Marguerite Harber, and great craic. -

AN INTRODUCTION to the ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE of COUNTY DONEGAL

AN INTRODUCTION TO THE ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE of COUNTY DONEGAL AN INTRODUCTION TO THE ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE of COUNTY DONEGAL COUNTY DONEGAL Mount Errigal viewed from Dunlewey. Foreword County Donegal has a rich architectural seventeenth-century Plantation of Ulster that heritage that covers a wide range of structures became a model of town planning throughout from country houses, churches and public the north of Ireland. Donegal’s legacy of buildings to vernacular houses and farm religious buildings is also of particular buildings. While impressive buildings are significance, which ranges from numerous readily appreciated for their architectural and early ecclesiastical sites, such as the important historical value, more modest structures are place of pilgrimage at Lough Derg, to the often overlooked and potentially lost without striking modern churches designed by Liam record. In the course of making the National McCormick. Inventory of Architectural Heritage (NIAH) The NIAH survey was carried out in phases survey of County Donegal, a large variety of between 2008 and 2011 and includes more building types has been identified and than 3,000 individual structures. The purpose recorded. In rural areas these include structures of the survey is to identify a representative as diverse as bridges, mills, thatched houses, selection of the architectural heritage of barns and outbuildings, gate piers and water Donegal, of which this Introduction highlights pumps; while in towns there are houses, only a small portion. The Inventory should not shopfronts and street furniture. be regarded as exhaustive and, over time, other A maritime county, Donegal also has a rich buildings and structures of merit may come to built heritage relating to the coast: piers, light. -

The Ulster Women's Unionist Council and Ulster Unionism

“No Idle Sightseers”: The Ulster Women’s Unionist Council and Ulster Unionism (1911-1920s) Pamela Blythe McKane A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN POLITICAL SCIENCE YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO JANUARY 2015 ©Pamela Blythe McKane 2015 Abstract Title: “No Idle Sightseers”: The Ulster Women’s Unionist Council and Ulster Unionism (1911-1920s) This doctoral dissertation examines the Ulster Women’s Unionist Council (UWUC), an overlooked, but historically significant Ulster unionist institution, during the 1910s and 1920s—a time of great conflict. Ulster unionists opposed Home Rule for Ireland. World War 1 erupted in 1914 and was followed by the Anglo-Irish War (1919- 1922), the partition of Ireland in 1922, and the Civil War (1922-1923). Within a year of its establishment the UWUC was the largest women’s political organization in Ireland with an estimated membership of between 115,000 and 200,000. Yet neither the male- dominated Ulster unionist institutions of the time, nor the literature related to Ulster unionism and twentieth-century Irish politics and history have paid much attention to its existence and work. This dissertation seeks to redress this. The framework of analysis employed is original in terms of the concepts it combines with a gender focus. It draws on Rogers Brubaker’s (1996) concepts of “nation” as practical category, institutionalized form (“nationhood”), and contingent event (“nationness”), combining these concepts with William Walters’ (2004) concept of “domopolitics” and with a feminist understanding of the centrality of gender to nation. -

Political-Cartoons.Pdf

Dublin City Library and Archive, 138 - 144 Pearse Street, Dublin 2. Tel: +353 1 6744999 Political Cartoons Date Newspaper Title Subtitle Location The Master of the ScRolls! Folder 04/01 The Extinguisher Folder 04/02 Ex Officio Examination Folder 04/03 A Theological Antidote firing off Lees of oppostition Folder 04/04 The New Hocus Pocus or Excellent escape, with the juglers all in an uproar Folder 04/05 founded on a new Sevic comic, Rattle Bottle Pantomine lately performed at the new Theatre Royal The Bottle Conjurers ARMS God Save the King: The Glorious and Immortal Memory Folder 04/06 Date c. 1810 1830 A Turning General and three and twenty Bottle holders Folder 04/07 all in a Row 01 June 2011 Page 1 of 84 Date Newspaper Title Subtitle Location Irish Fireside The Old, Old Home! Box 01 F01/07 The Lepracaun Box 06/47 The Lepracaun Box 06/48 United Ireland The Suppression of the League, or Catching a Tartar Bloody Balfour- Hello Uncle, I've caught a Tartar Folder 01/42 Salisbury- Dragf him along here B.B.- I cant 14/08/1869 Vanity Fair Statesmen, No. 28 "He married Lady Waldegrave and governed Ireland" Box 01 F05/01 09/04/1870 Vanity Fair Statesman No. 46 "An exceptional Irishman" Box 01 F05/02 25/03/1871 Vanity Fair Statesmen, No. 79 "An Irish wit and Solicitor-General" Box 01 F05/03 30/12/1871 Vanity Fair Statesmen No. 102 "An Art critic" Box 01 F05/04 23/03/1872 Vanity Fair Statesmen, No. 109 "A Home Ruler" Box 01 F05/05 28/09/1872 Vanity Fair Statesmen, No. -

Bibliography

BIbLIOGRApHY PRIMARY SOURCEs: ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS BODLEIAN LIbRARY, OXFORD H. H. Asquith BRITIsH LIbRARY Walter Long CLAYDON EsTATE, BUCKINGHAMsHIRE Harry Verney IRIsH MILITARY ARCHIVEs Bureau of Military History Contemporary Documents Bureau of Military History Witness Statements (http://www.bureauofmilitaryhis- tory.ie) Michael Collins George Gavan Duffy © The Author(s) 2019 305 M. C. Rast, Shaping Ireland’s Independence, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-21118-9 306 BIblIOgraPhY NATIONAL ARCHIVEs OF IRELAND Dáil Éireann Debates (http://oireachtas.ie) Dáil Éireann Documents Department of the Taoiseach Documents on Irish Foreign Policy (printed and http://www.difp.ie) NATIONAL LIbRARY OF IRELAND G. F. Berkeley Joseph Brennan Bryce Erskine Childers George Gavan Duffy T. P. Gill J. J. Hearn Thomas Johnson Shane Leslie Monteagle Maurice Moore Kathleen Napoli McKenna Art Ó Briain William O’Brien (AFIL) J. J. O’Connell Florence O’Donoghue Eoin O’Duffy Horace Plunkett John Redmond Austin Stack NEW YORK PUbLIC LIbRARY Horace Plunkett, The Irish Convention: Confidential Report to His Majesty the King by the Chairman (1918). PUbLIC RECORD OFFICE NORTHERN IRELAND J. B. Armour J. Milne Barbour Edward Carson Craigavon (James Craig) BIblIOgraPhY 307 Adam Duffin Frederick Crawford H. A. Gwynne Irish Unionist Alliance Theresa, Lady Londonderry Hugh de Fellenberg Montgomery Northern Ireland Cabinet Ulster Unionist Council Unionist Anti-Partition League Lillian Spender Wilfrid B. Spender The Stormont Papers: Northern Ireland Parliamentary Debates (http://stor- -

O'brien Cahirmoyle LIST 64

Leabharlann Naisiúnta na hÉireann National Library of Ireland Collection List No. 64 PAPERS OF THE FAMILY OF O’BRIEN OF CAHIRMOYLE, CO. LIMERICK (MSS 34,271-34,277; 34,295-34,299; 36,694-36,906) (Accession No. 5614) Papers of the descendents of William Smith O’Brien, including papers of the painter Dermod O’Brien and his wife Mabel Compiled by Peter Kenny, 2002-2003 Contents Introduction 7 The family 7 The papers 7 Bibliography 8 I. Land tenure 9 I.1. Altamira, Co. Cork 9 I.2 Ballybeggane 9 I.3. Bawnmore 9 I.4. Cahirmoyle 9 I.5. Clanwilliam (Barony) 11 I.6. Clorane 11 I.7. The Commons, Connello Upper 11 I.8. Connello (Barony) 11 I.9. Coolaleen 11 I.10. Cork City, Co. Cork 11 I.11. Dromloghan 12 I.12. Garrynderk 12 I.13. Glanduff 12 I.14. Graigue 12 I.15. Killagholehane 13 I.16. Kilcoonra 12 I.17. Killonahan 13 I.18. Killoughteen 13 I.19. Kilmurry (Archer) 14 I.20. Kilscannell 15 I.21. Knockroedermot 16 I.22. Ligadoon 16 I.23. Liscarroll, Co. Cork 18 I.24. Liskillen 18 I.25. Loghill 18 I.26. Mount Plummer 19 I.27. Moyge Upper, Co. Cork 19 I.28. Rathgonan 20 2 I.29. Rathnaseer 21 I.30. Rathreagh 22 I.31. Reens 22 I.32 Correspondence etc. relating to property, finance and legal matters 23 II. Family Correspondence 25 II.1. Edward William O’Brien to his sister, Charlotte Grace O’Brien 25 II.2. Edward William O’Brien to his sister, Lucy Josephine Gwynn (d. -

Newsletter No

The Irish Garden Plant Society Newsletter No. 133 September 2015 In this issue 1 Editorial 2 A word from the Chair 3 Myddelton House, the garden of E.A. Bowles by Dr. Mary Forrest 6 My memories of the Irish Gardeners’ Association by Thomas Byrne 13 The 34 th Annual General Meeting May 2015 18 Worth a read by Paddy Tobin 21 Notes on some Irish Plants by Paddy Tobin 24 Memories are made of plants by Carmel Duignan 26 Irish heritage plants update by Stephen Butler 27 Seed Distribution Scheme 2015/16 by Stephen Butler 28 Regional reports 34 A Wonderful Project – Plandaí Oidhreachta by Paddy Tobin 36 Aubrieta 'Shangarry' by Edel McDonald and Brendan Sayers 38 Details of upcoming events organised by the regional committees Front cover photograph of Escallonia ‘Glasnevin Hybrid’ courtesy of Pearse Rowe. This is one of a number of Escallonia cultivars raised by Charles Frederick Ball at Glasnevin where he worked as Assistant Keeper before joining the 7th Royal Dublin Fusiliers in World War l. Escallonia ‘Alice’ was named by Ball for his wife, he married in December 1914. The more widely available E. ‘C.F. Ball’ was named in his honour after his death; he died aged 36 years from shrapnel wounds at Gallipoli on 13 th September 1915. In his obituary he was described as “a delightful companion, unassuming, sincere and a most lovable man”. Editorial Dr. Mary Forrest on page 3 writes of a visit to Myddelton House London, the home of E. A. Bowles. In Moorea volume 15 Mary included in a list of horticultural trade organisations of the early 20 th century the Irish Gardeners’ Association. -

Maria Forde Ireland Celtic Tour

2020 Maria Forde Ireland Celtic Tour 19 SEPTEMBER – 03 OCTOBER 15 Days / 14 Nights CONTACT: Suite 1A, 339 Ferrars Street South Melbourne VIC 3205 TEL: 03 9690 2123 DAY ONE DAY TWO DAY THREE Saturday, 19 September 2020 Sunday, 20 September 2020 Monday, 21 September 2020 ARRIVE DUBLIN DUBLIN HIGHLIGHTS KILMOKEA GARDENS & WEXFORD Land at Dublin Airport, complete customs and Set off with a local guide who will show you This morning, we head to New Ross and visit immigration formalities before meeting your around Dublin. The city has been molded Dunbrody Emigrant Ship, a replica of a sailing driver, who will welcome you to Ireland through the centuries by economic, political vessel built in 1845. The visit will give you an Transfer to your hotel, check in and settle into and artistic influences that has shaped its insight as to what life on board ship was like as your room. architecture. Stop at Trinity College to see the well as filling you in on the history of the famine Book of Kells, an 8th century illuminated years. You will have the day at leisure manuscript of the gospels and see the Old Library. Tour Guinness Storehouse to see We continue our travels to Campile and visit the There are plenty of museums of Irish interest exhibits on how this world-famous stout was first gardens at Kilmokea Gardens. The gardens are such as the National Museum, the National created and why it is so popular today. Finish divided into two distinct parts. Around the Gallery or the Writers Museum, EPIC Ireland. -

Book Auction Catalogue

1. 4 Postal Guide Books Incl. Ainmneacha Gaeilge Na Mbail Le Poist 2. The Scallop (Studies Of A Shell And Its Influence On Humankind) + A Shell Book 3. 2 Irish Lace Journals, Embroidery Design Book + A Lace Sampler 4. Box Of Pamphlets + Brochures 5. Lot Travel + Other Interest 6. 4 Old Photograph Albums 7. Taylor: The Origin Of The Aryans + Wilson: English Apprenticeship 1603-1763 8. 2 Scrap Albums 1912 And Recipies 9. Victorian Wildflowers Photograph Album + Another 10. 2 Photography Books 1902 + 1903 11. Wild Wealth – Sears, Becker, Poetker + Forbeg 12. 3 Illustrated London News – Cornation 1937, Silver Jubilee 1910-1935, Her Magesty’s Glorious Jubilee 1897 13. 3 Meath Football Champions Posters 14. Box Of Books – History Of The Times etc 15. Box Of Books Incl. 3 Vols Wycliff’s Opinion By Vaughan 16. Box Books Incl. 2 Vols Augustus John Michael Holroyd 17. Works Of Canon Sheehan In Uniform Binding – 9 Vols 18. Brendan Behan – Moving Out 1967 1st Ed. + 3 Other Behan Items 19. Thomas Rowlandson – The English Dance Of Death 1903. 2 Vols. Colour Plates 20. W.B. Yeats. Sophocle’s King Oedipis 1925 1st Edition, Yeats – The Celtic Twilight 1912 And Yeats Introduction To Gitanjali 21. Flann O’Brien – The Best Of Myles 1968 1st Ed. The Hard Life 1973 And An Illustrated Biography 1987 (3) 22. Ancient Laws Of Ireland – Senchus Mor. 1865/1879. 4 Vols With Coloured Lithographs 23. Lot Of Books Incl. London Museum Medieval Catalogue 24. Lot Of Irish Literature Incl. Irish Literature And Drama. Stephen Gwynn A Literary History Of Ireland, Douglas Hyde etc 25. -

Joseph Maunsell Hone Papers P229 UCD ARCHIVES

Joseph Maunsell Hone Papers P229 UCD ARCHIVES [email protected] www.ucd.ie/archives T + 353 1 716 7555 F + 353 1 716 1146 © 2009 University College Dublin. All Rights Reserved ii CONTENTS CONTEXT Biographical History iv Archival History iv CONTENT AND STRUCTURE Scope and Content v System of Arrangement vi CONDITIONS OF ACCESS AND USE Access vii Language vii Finding Aid vii DESCRIPTION CONTROL Archivist’s Note vii iii CONTEXT Biographical history Born in Dublin in February 1882, Joseph Maunsell Hone was educated at Wellington and Jesus College, Cambridge and began a writing career which gained him a reputation as a leading figure of the Irish literary revival. He wrote well regarded biographies of George Moore (1939), Henry Tonks (1936), and W.B. Yeats (1943) with whom he was on terms of close friendship. His political writings included books on the 1916 rebellion, the Irish Convention, and a history of Ireland since independence, published in 1932. He had a strong interest in philosophy, translating Daniel Halévy’s life of Nietzsche and working with Arland Ussher on an anthology of philosophers which was never completed. He was elected President of the Irish Academy of Letters in 1957. With George Roberts and Stephen Gwynn, he co-founded Maunsel & Company, publishers, and served as its chairman. The company published more than five hundred titles to become Ireland’s largest publishing house, publishing works by all the revival’s leading figures. The imprint later changed to Maunsel & Roberts. Joseph Hone died in March 1959 and was survived by his wife Vera (neé Brewster), a noted beauty from New York who he had married in 1911.