COMPETITIVENESS and POTENTIAL in SPAS and HEALTH RESORTS in SOME CENTRAL EUROPEAN REGIONS (Conclusions from On-Going Research in South Transdanubia, Hungary)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Act Cciii of 2011 on the Elections of Members Of

Strasbourg, 15 March 2012 CDL-REF(2012)003 Opinion No. 662 / 2012 Engl. only EUROPEAN COMMISSION FOR DEMOCRACY THROUGH LAW (VENICE COMMISSION) ACT CCIII OF 2011 ON THE ELECTIONS OF MEMBERS OF PARLIAMENT OF HUNGARY This document will not be distributed at the meeting. Please bring this copy. www.venice.coe.int CDL-REF(2012)003 - 2 - The Parliament - relying on Hungary’s legislative traditions based on popular representation; - guaranteeing that in Hungary the source of public power shall be the people, which shall pri- marily exercise its power through its elected representatives in elections which shall ensure the free expression of the will of voters; - ensuring the right of voters to universal and equal suffrage as well as to direct and secret bal- lot; - considering that political parties shall contribute to creating and expressing the will of the peo- ple; - recognising that the nationalities living in Hungary shall be constituent parts of the State and shall have the right ensured by the Fundamental Law to take part in the work of Parliament; - guaranteeing furthermore that Hungarian citizens living beyond the borders of Hungary shall be a part of the political community; in order to enforce the Fundamental Law, pursuant to Article XXIII, Subsections (1), (4) and (6), and to Article 2, Subsections (1) and (2) of the Fundamental Law, hereby passes the following Act on the substantive rules for the elections of Hungary’s Members of Parliament: 1. Interpretive provisions Section 1 For the purposes of this Act: Residence: the residence defined by the Act on the Registration of the Personal Data and Resi- dence of Citizens; in the case of citizens without residence, their current addresses. -

Communication from the Minister for National

13.6.2017 EN Official Journal of the European Union C 187/47 Communication from the Minister for National Development of Hungary pursuant to Article 3(2) of Directive 94/22/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on the conditions for granting and using authorisations for the prospection, exploration and production of hydrocarbons (2017/C 187/14) PUBLIC INVITATION TO TENDER FOR A CONCESSION FOR THE PROSPECTION, EXPLORATION AND PRODUCTION OF HYDROCARBON UNDER CONCESSION IN THE SOMOGYVÁMOS AREA On behalf of the Hungarian State, the Minister for National Development (‘the Contracting Authority’ or ‘the Minister’) as the minister responsible for mining and for overseeing state-owned assets hereby issues a public invitation to tender for the prospection, exploration and production of hydrocarbon under a concession contract on the basis of Act CXCVI of 2011 on national assets (‘the National Assets Act’), Act XVI of 1991 on Concessions (‘the Concessions Act’) and Act XLVIII of 1993 on mining (‘the Mining Act’), subject to the following conditions. 1. The Minister will publish the invitation to tender, adjudge the bids and conclude the concession contract in coop eration with the Hungarian Office for Mining and Geology (Magyar Bányászati és Földtani Hivatal) in accordance with the Concessions Act and the Mining Act. Bids that meet the tender specifications will be evaluated by an Evaluation Committee set up by the Minister. On the recommendation of the Evaluation Committee the Minister will issue the decision awarding the concession, on the basis of which the Minister may then conclude the concession contract with the successful bidder in accordance with Section 5(1) of the Concessions Act (1). -

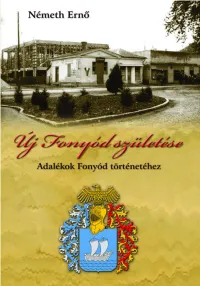

Új Fonyód Születése

Németh Ernô Új Fonyód születése Fonyód várossá avatásának 25. évfordulójára Németh Ernô Új Fonyód születése Adalékok Fonyód történetéhez Fonyód, 2015 Írta és szerkesztette: Németh Ernő A kézirat lezárásának éve: 2015 Minden jog fenntartva. Bármilyen másolás, sokszorosítás illetve adatszolgáltató rendszerben való tárolás a kiadó elôzetes írásbeli hozzájárulásához van kötve. ISBN 978-963-12-1895-4 © Németh Ernô Magánkiadás Borítóterv: Matucza Ferenc Nyomdai munkák: Centrál Press Nyomda Kaposvár Felelôs vezetô: Nagy László Zsoldos László Tartalom Előszó ............................................................................................................... 9 Bevezetés ........................................................................................................ 11 A KÖZIGAZGATÁS ÁTALAKÍTÁSA ............................................................... 12 A tanácsrendszer bevezetése ...................................................................... 12 A megyei tanács megalakulása .................................................................. 12 Fonyód járási székhely lett ....................................................................... 14 A járási tanács megalakulása ..................................................................... 17 A végrehajtó bizottság szervezeti rendszerének kialakítása ..................... 20 A járási hivatal elhelyezése ....................................................................... 21 A járási tanács személyi állományának kiválasztása ................................. -

February 2009 with the Support of the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany & the Conference of European Rabbis

Lo Tishkach Foundation European Jewish Cemeteries Initiative Avenue Louise 112, 2nd Floor | B-1050 Brussels | Belgium Telephone: +32 (0) 2 649 11 08 | Fax: +32 (0) 2 640 80 84 E-mail: [email protected] | Web: www.lo-tishkach.org The Lo Tishkach European Jewish Cemeteries Initiative was established in 2006 as a joint project of the Conference of European Rabbis and the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany. It aims to guarantee the effective and lasting preservation and protection of Jewish cemeteries and mass graves throughout the European continent. Identified by the Hebrew phrase Lo Tishkach (‘do not forget’), the Foundation is establishing a comprehensive publicly-accessible database of all Jewish burial grounds in Europe, currently featuring details on over 9,000 Jewish cemeteries and mass graves. Lo Tishkach is also producing a compendium of the different national and international laws and practices affecting these sites, to be used as a starting point to advocate for the better protection and preservation of Europe’s Jewish heritage. A key aim of the project is to engage young Europeans, bringing Europe’s history alive, encouraging reflection on the values that are important for responsible citizenship and mutual respect, giving a valuable insight into Jewish culture and mobilising young people to care for our common heritage. Preliminary Report on Legislation & Practice Relating to the Protection and Preservation of Jewish Burial Grounds Hungary Prepared by Andreas Becker for the Lo Tishkach Foundation in February 2009 with the support of the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany & the Conference of European Rabbis. -

Possibilities of Including Roma Population in Ecotourism Development of Koprivnica-Križevci County

RESEARCH STUDY POSSIBILITIES OF INCLUDING ROMA POPULATION IN ECOTOURISM DEVELOPMENT OF KOPRIVNICA-KRIŽEVCI COUNTY Sandra Kantar Kristina Svržnjak INVOLVEMENT OPPORTUNITIES OF THE ROMA POPULATION IN ECOTOURISM Viktória Szente Attila Pintér Orsolya Szigeti POSSIBILITIES OF INCLUDING ROMA POPULATION IN ECOTOURISM DEVELOPMENT OF KOPRIVNICA-KRIŽEVCI COUNTY Sandra Kantar Kristina Svržnjak Križevci College of Agriculture 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................................... 5 1.1. PROJECT PURPOSE, OBJECTIVES AND ACTIVITIES .............................................................................................................................................. 5 1.2. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY ........................................................................................................................................................................................ 6 2. CHALLENGES OF ECOTOURISM DEVELOPMENT IN KOPRIVNICA-KRIŽEVCI COUNTY: RESULTS OF RESEARCH CONDUCTED WITHIN »ECOTOP« PROJECT ......................................................................................... 7 3. ROMA COMMUNITY IN THE REPUBLIC OF CROATIA ........................................................................................... 9 3.1. DEMOGRAPHIC DATA ABOUT ROMA POPULATION IN THE REPUBLIC OF CROATIA ............................................................................... 10 3.2. ROMA POPULATION IN KOPRIVNICA-KRIŽEVCI -

Regional Development

HUHR/1101/2.1.4/0005 Sectoral Studies: 1., Regional Development Regional Development Contents Situation Analysis .................................................................................................................. 2 Local Infrastructure, Urban Development .......................................................................... 2 Hierarchy of Settlements................................................................................................ 3 Public Services .................................................................................................................. 5 Local Economic Development ........................................................................................... 6 Economic Development, Economic Sectors................................................................... 6 Characteristics of Entrepreneurship ............................................................................... 8 Local Economic Characteristics ..................................................................................... 9 Business Infrastructure .....................................................................................................13 Stakeholder Analysis ............................................................................................................14 National and Local Actors Interested in Regional Development ........................................14 Government Office for Somogy County ........................................................................14 Széchenyi Program -

Lake Balaton and Sustainable Tourism Development (Hungary)

Lake Balaton and sustainable tourism development (Hungary) Nanchang, 21th November 2014 14th Living Lakes Conference Zita Egerszegi environmental director Lake Balaton Development Coordination Agency Location • Central-Europe • Carpathian basin Nature – the Lake and its surroundings • Largest freshwater lake in Central Europe • Natural shallow lake, average depth is 3.2 m • Lake surface area is 600 sqkm - Flora and fauna • One of the most significant natural treasure of Hungary, a unique ecological asset of the CE region • Large areas of nature and landscape protection, such as the Balaton Upland National Park, and Ramsar sites Nature – Facts number • 2000 species of algae • 1200 species of invertebrates • 41 species of fish • 616 km2 protected area, of which 147 km2 is under Ramsar Convention • Natura 2000 sites 1981 km2 (43 sites) • 207 species of protected plants • 37 species of protected animals Ecosystem services • Provisioning services (food, water, row material…) • Regulating services (climate regulation, purification of water, pest and disease control) • Cultural services (recreational experiences, ecotourism, science, education, painting, folklore) People – Culture and History • Cultural values, heritage sites, folk art as well as events cultivating these traditions and memories are determinative factors in developing the regional image. • The permanent population is about 275.000 people, considering the families of weekend house owners it rises well above 500.000 people. • In summer time, taking into account tourists and visitors, as well, the number of population increases up to 1-2 million people. Economy – Tourism: the driving force of the economy • Bathing in Lake Balaton started in 19th century. • About one third of tourism related revenues in Hungary are generated in the Lake Balaton Region. -

A Study on the Competitiveness Factors of Spas and Health Resorts in Hungary and Neighbouring Central European Regions*

MÁRTA BAKUCZ, Dr. Associate Professor University of Pécs, Faculty of Business & Economics 7622 Pécs, Rákóczi út 80, Hungary +36 (72) 501-599/23386 [email protected] A STUDY ON THE COMPETITIVENESS FACTORS OF SPAS AND HEALTH RESORTS IN HUNGARY AND NEIGHBOURING CENTRAL EUROPEAN REGIONS* Abstract The paper covers two topics which are, broadly, inseparable. The first has as its main target the competitiveness of Spa Tourism in two Regions of Hungary - in settlements with different characteristics; the second, recognising the need for a new way to measure competitiveness in the sector, deals with the creation of a new competitiveness index. The benefits of virtually all forms of Tourism - economic or social – are well enough known to need no repetition. This is especially true of such fields as Spa or Health Tourism, in which there is a natural trend towards longer stays and higher expenditure by visitors. For a relatively poor country such as Hungary – weak in natural resources apart from agricultural land – the basic presence of a generous supply of easily accessible thermal or medicinal water below a huge proportion of its surface area (70%) is a remarkable gift. Nevertheless, many factors are to be studied if a rational, sustainable development policy is to be elaborated by public and private interests. There are many spas – settlements with thermal or medicinal waters (or both) - spread across Hungary, and their variety is extraordinary. There are huge differences in terms of size, visitor numbers, accommodation facilities, overnights, leisure or treatment facilities and location – that is, their closeness to favourable population areas (domestic or foreign). -

An Analytical, Evaluation and Comparative Study Conducted on the Implemented Tourism Investments in the Border Region of Hungary and Croatia

An analytical, evaluation and comparative study conducted on the implemented tourism investments in the border region of Hungary and Croatia Hungary-Croatia IPA Cross-border Co-operation Programme 2007-2013 HUHR/1101/1.2.5/0003 Written by: Zala Wine Route Association on behalf of Zala County Chamber of Commerce and Industry 2013 An analytical, evaluation and comparative study conducted on the implemented tourism investments in the border region of Hungary and Croatia CONTENT 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Description of the project ................................................................................ 2 1.2 The purpose and subject of the study............................................................... 2 1.3 Description of the method of investigation...................................................... 3 2. THE GENERAL POSITION OF THE BORDER REGION, THE STATE AND OPPORTUNITIES OF TOURISM SECTOR ........................................................................................................ 5 2.1 Situation analysis ............................................................................................. 5 2.2 Strategy of tourism development in the target area on the basis of planning documents ................................................................................................................. 10 3. DESCRIPTION OF TOURISM DEVELOPMENTS IMPLEMENTED IN THE BORDER REGION OF HUNGARY AND CROATIA ......................................................................................... -

Local Economic and Employment Development : Business Clusters

Business Clusters PROMOTING ENTERPRISE IN CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPE Business Clusters of firms and related organisations in a range of industry specialisations are a striking feature of the economic landscape in all countries. Their growth and survival depends on Clusters internal processes of specialisation, co-operation and rivalry, and knowledge flows that underpin the competitiveness of the firms within them. Cluster building is now among the PROMOTING ENTERPRISE most important economic development activities in OECD countries and beyond. This book looks at the importance and potential of cluster initiatives in Central and Eastern Europe as IN CENTRAL AND these countries integrate ever more strongly into the global economy. Existing clusters are EASTERN EUROPE mapped, recent policy advances are described and conclusions are drawn on the potential of business clusters to foster economic growth in the wider Central, East and South East European region. CLUSTERS: BUSINESS Do clusters only occur spontaneously or can they be formally encouraged? What role do public authorities play? What, if any, is the impact of specific national political and economic initial conditions on cluster development? Which policies work best? These are just some of the questions raised in this publication, which provides practical insights on clusters and cluster policies to governments, local development practitioners and entrepreneurs alike. This publication is one of the outputs of a major programme of conferences and research on cluster building in Central and Eastern Europe led by the OECD LEED Programme in collaboration with the Central European Initiative and the European Bank for Reconstruction Europe Eastern and Central in Enterprise Promoting and Development. -

Discussion Papers

CENTRE FOR REGIONAL STUDIES OF HUNGARIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES DISCUSSION PAPERS No. 61 Development Issues of the Balaton Region by Attila Buday-Sántha Series editor Zoltán GÁL Pécs 2007 Supported by the OTKA (Hungarian Scientific Research Fund) Grant No. T 046964 KGJ. Read by Gyula Bora, Miklós Oláh. Translated by Zoltán Raffay. ISSN 0238–2008 ISBN 978 963 9052 92 5 2007 by Centre for Regional Studies of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. Technical editor: Ilona Csapó. Printed in Hungary by Sümegi Nyomdaipari, Kereskedelmi és Szolgáltató Ltd., Pécs. 2 Contents 1 Preface ...................................................................................................................... 8 2 Characteristics and history of the Balaton region ................................................... 11 2.1 The physical geography of the Lake Balaton ................................................. 11 2.2 The administrative conditions of the Balaton region ...................................... 17 2.3 History of the Lake Balaton............................................................................ 18 3 Population, employment and incomes in the Balaton region ................................. 41 3.1 Demographic situation of the Balaton Region ................................................ 41 3.2 Training and education ................................................................................... 45 3.3 Employment of the labour force ..................................................................... 46 3.4 Incomes ......................................................................................................... -

Iskolai Felvételi Körzethatárok Tervezete a 2021/2022-Es Tanévre a Siófoki Tankerületi Központ Feladatellátási Területén

8600 Siófok, Szépvölgyi utca 2. Telefon: +36 (84) 795-236 E-mail: [email protected] Iskolai felvételi körzethatárok tervezete a 2021/2022-es tanévre a Siófoki Tankerületi Központ feladatellátási területén A tanuló A tanuló körzeti Feladatellátási hely Feladatellátási hely lakóhelye, iskolája címe tartózkodási helye melyik településen van (A: alsó tagozat, F: felső tagozat; évfolyam) 2021/2022 FONYÓD Fonyód Palonai Magyar 8640 Fonyód, Fő Bálint Általános utca 8. Iskola Balatonboglár Balatonboglár Boglári Általános 8630 Balatonboglár, Iskola és Alapfokú Árpád utca 5. Művészeti Iskola Balatonfenyves Balatonfenyves Balatonfenyvesi 8646 Fekete István Balatonfenyves, Általános Iskola Kölcsey utca 38-39. Balatonlelle Balatonlelle Balatonlelle-Karádi 8638 Balatonlelle, Általános Iskola és Petőfi utca 1. Alapfokú Művészeti Iskola Buzsák Buzsák Buzsáki Általános 8695 Buzsák, Fő tér Iskola 2. Gamás Gamás Gamási Általános 8685 Gamás, Fő Iskola utca 94. Gyugy Lengyeltóti Fodor András 8693 Lengyeltóti, Általános Iskola, Csokonai utca 15. Alapfokú Művészeti Iskola Hács Lengyeltóti Fodor András 8693 Lengyeltóti, Általános Iskola, Csokonai utca 15. Alapfokú Művészeti Iskola Siófoki Tankerületi Központ 8600 Siófok, Szépvölgyi utca 2. Telefon: +36 (84) 795-236 E-mail: [email protected] 1 8600 Siófok, Szépvölgyi utca 2. Telefon: +36 (84) 795-236 E-mail: [email protected] Karád Karád A: Balatonlelle- A:8676 Karád, Karádi Általános Gárdonyi utca 2. Iskola Gárdonyi Géza Tagiskolája F: Balatonlelle- F: 8676 Karád, Karádi Általános Kossuth park Iskola Gárdonyi 1057/2. Gézas Tagiskola Kossuth Parki Telephelye Kisberény felmenő Buzsáki Általános 8695 Buzsák, Fő tér rendszerben a Iskola 2. 2020/2021-es tanévtől Buzsák Látrány Látrány Látrányi Fekete 8681 Látrány, István Általános Szabadság utca 11. Iskola és Alapfokú Művészeti Iskola Lengyeltóti Lengyeltóti Fodor András 8693 Lengyeltóti, Általános Iskola, Csokonai utca 15.