The Table-Talk of a Mesopotamian Judge, Being the First Part of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Lo Ndo N Soas the Umayyad Caliphate 65-86

UNIVERSITY OF LONDON SOAS THE UMAYYAD CALIPHATE 65-86/684-705 (A POLITICAL STUDY) by f Abd Al-Ameer 1 Abd Dixon Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philoso] August 1969 ProQuest Number: 10731674 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10731674 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 2. ABSTRACT This thesis is a political study of the Umayyad Caliphate during the reign of f Abd a I -M a lik ibn Marwan, 6 5 -8 6 /6 8 4 -7 0 5 . The first chapter deals with the po litical, social and religious background of ‘ Abd al-M alik, and relates this to his later policy on becoming caliph. Chapter II is devoted to the ‘ Alid opposition of the period, i.e . the revolt of al-Mukhtar ibn Abi ‘ Ubaid al-Thaqafi, and its nature, causes and consequences. The ‘ Asabiyya(tribal feuds), a dominant phenomenon of the Umayyad period, is examined in the third chapter. An attempt is made to throw light on its causes, and on the policies adopted by ‘ Abd al-M alik to contain it. -

6 X 10.Long New.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-51517-7 - The Languages of Gift in the Early Middle Ages Edited by Wendy Davies and Paul Fouracre Index More information Index al-Abbas b. al-Hasan, vizier, 152 Arlanza, monastery, 222 Abd al-Hamid ibn Yahya, 158 Artemios, saint, 36 Abd al-Rahman III, caliph, 157 Aruin, duke, 134 Abellar, monastery, 229 Athala, abbot, 97 Abu Bakr Muhammad, 154 Athanasios of Athos, saint, 178, 179, 182, AbuUthmanSa’d,154 186, 188 Adalard, 140 Athos, mount, 13, 33, 116, 192, 247, Adalbert II, marquis of Tuscany, 150, 151, 253 152, 250 Iviron monastery, 13, 180, 183, 185, adventus, 194, 262 189, 190, 191 Ælffled, 102 Lavra, 176, 178, 182, 183, 185, 186, Æthelwold Moll, king, 101, 102 187, 188, 191 al-Afdal, 158 Auden, W. H., 14 Agatho, pope, 96, 105, 240 Audiperto of Brioni, 197 Agde, council of, 30 Augustine of Hippo, 26, 27, 30, 67 agros, 185, 262 Augustus, emperor, 133 Aidan, saint, 110, 250 al-Awhadi, 153 Ai’isha, wife of Muhammad, 166 al-‘Aziz, caliph, 166 Airlie, Stuart, 146 al-Azmeh, 168 Albelda, monastery, 222 Alchfrith, 103 Bagaudano, 229 Alcuin, 125, 129, 139, 251 Balthild, queen, 249 Aldfrid, king, 105, 113 Basil I, emperor, 48, 50, 52, 57, 59 Aldfrith, abbot, 100, 104, 106 Basil II, emperor, 47, 188, 189, 190 Alexander, emperor, 50, 51, 56, 58 Bede, 10, 30, 89–115, 240 Alexander the Great, 133 Historia Abbatum, 89, 93, 96, 109 Alexios I, emperor, 48, 55 Historia Ecclesiastica, 92 Algazi, Gadi, 2, 3 Vita Cuthberti, 102 Alhfrid, sub-king, 101 bema, 46, 262 ‘Ali, caliph, 166 Benedict Biscop, 90–115 ‘Ali ibn Khalaf, -

Forgotten Queens F19 Syllabus

HIS 381: The Forgotten Queens of Islam Fall 2019 Tuesdays and Thursdays, 11:00 AM – 12:15 PM Main Hall 402 Syllabus Professor: Dr. Elizabeth Urban Office: Wayne Hall 713 EMail: [email protected] Office Hours: TBA Phone: (610) 436-2541 Course Description: For the Past 1,400 years, woMen have had a Profound iMPact on institutions and ideologies in the Islamic world. They have Mastered branches of knowledge, Produced works of culture, amassed wealth, and eVen ruled as queens. In this course, students will read about ProMinent women's lives in historical texts froM the Islamic world, focusing on the Period froM 600–1700 CE. Students will learn to read these historical texts "against the grain" through the lens of feMinist history, which uses feMale PersPectiVes to reframe and reconfigure our understanding of the Past. By the end of the course, students will be equiPPed to analyze the Various forMs of Power that have historically been available (and unavailable) to woMen the Islamic Middle East, and to assess the Many ways woMen have navigated unequal Power structures in order to ParticiPate in their Polities. The course will also equiP students to articulate an informed, reasoned oPenness to differences related to issues such as: gender roles, family structures (including concubinage and polygyny), clothing/veiling, sex segregation (including the hareM institution), sexuality, and legal status (particularly, the Many complex Meanings of slaVery and freedom). This course challenges students to MoVe beyond siMPle, binary thinking when considering woMen froM the Islamic Middle East. Such woMen have neVer been either PassiVe, oPPressed VictiMs on the one hand, or fully liberated, agentiVe indiViduals on the other. -

University Microfilms

INFORMATION TO USERS This dissertation was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

In the Medieval Islamic World

LEGACY OF ARABIC MEDICINE Female Patients, Patrons and Practitioners In the medieval Islamic world – Written by Peter E. Pormann, UK Women constitute roughly half the FEMALE PATRONS increased the endowment of the hospital population. This is true now as it must Patronage played a powerful role in the founded by Badr al-Mu‘tadidi (d. 902), have been during the heyday of the Islamic provision of health services. In ‘Abbasid the commander-in-chief of the caliph al- medieval period. The sources from this times, caliphs, viziers and other high- Mu‘tadid (r. 892-902). time, however, whether medical writings, ranking officials sponsored the building histories or works of literature, were mostly of hospitals, the digging of wells and in The Mistress written by men, for men. Male doctors one case even the improvement of access The most powerful woman in ‘Abbasid sometimes even vilified women and put to medical services in prisons and remote times, however, was Shaghab, the mother them into the same category as charlatans, areas. It was not only men, however, who of the caliph al-Muqtadir (r. 908-32). Her the proverbial ‘medical others’. It is therefore financed these charitable activities. Women son became caliph at the tender age of not surprising that the woman’s voice only occasionally rose to some prominence in 13 and remained devoted to his mother reaches us faintly across the centuries. And the palaces of the powerful. For instance, throughout his life. She turned the harem yet, by combining a range of variegated Khayruzan (d. 789) and Zubayda (d. -

Ill. BIBLIOGRAPHICAL REFERENCES

Ill. BIBLIOGRAPHICAL REFERENCES IlI.1. Primary sources § 1. Manuscripts used Dunquz, Sar/:! = Dunquz, Sar/:! al-marii/:!, 100311585, private. Dunquz, Sar/:! B = Dunquz, Sar/:! al-marii/:! B, 959 A.H.l1527, owned by the Department of Middle East languages at Lund University. Ibn Mas'Ud, MS A = Ai,lmad b. 'AU b. Mas'ud, Marii/:! al-arwii/:!, 4166, 947/1540, Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris. Ibn Mas'ud, MS B = Ai,lmad b. 'AU b. Mas'ud, Marii/:! al-arwii/:!, 4167, 966/1559, Bibliotheque NationaIe, Paris. Ibn Mas'ud, MS C = Ai,lmad b. 'AU b. Mas'ud, Marii/:! al-arwii/:!, 4168, 16th century A.D., Bibliotheque NationaIe, Paris. Ibn Mas'ud, MS D = Ai,lmad b. 'AU b. Mas'Ud, Marii/:! al-arwii/:!, 4169, 16th century A.D., Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris. Ibn Mas'ud, MS E = Ai,lmad b. 'AU b. Mas'ud, Marii/:! al-arwii/:!, 4170, 16th century A.D., Bibliotheque NationaIe, Paris. Ibn Mas'Ud, MS G = Ai,lmad b. 'AU b. Mas'ud, Marii/:! al-arwii/:!, 4172, 16th century A.D., Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris. Ibn Mas'ud, MS H = Ai,lmad b. 'AU b. Mas'ud, Marii/:! al-arwii/:!, 4173, 1033/1624, Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris. Ibn Mas'Ud, MS 1 = Ai,lmad b. 'AU b. Mas'ud, Marii/:! al-arwii/:!, 4174, 17th century A.D., BibIiotheque NationaIe, Paris. Ibn Mas'ud, MS J = Ai,lmad b. 'AU b. Mas'Ud, Marii/:! al-arwii/:!, 4182, 18th century A.D., Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris. Nlksm, Mifrii/:! = Nlksm, J:Iasan Pasa b. 'Alii'a I-DIn al-Aswad, the commentary al-Mifrii/:! fi sar/:! al-marii/:!,18th century, private. -

AL-Qa'da of the Kharijites, Their Principles and Ideas from Their Inception Until the End of the Reign of Yazid Ibn Mu'awiyah (41-64 / 661-683)

Historical Research Letter www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-3178 (Paper) ISSN 2225-0964 (Online) Vol.50, 2019 AL-Qa'da of the Kharijites, Their Principles and Ideas From Their Inception Until the End of the Reign of Yazid Ibn Mu'awiyah (41-64 / 661-683) Dr- zaid Ghandi Altalafha Part-time lecturer Faculty of Arts and Humanities, department of History Abstract This study aims to highlight the opinions and principles of Al-Qa'da,as a division of the most important Kharijites who were instrumental in the political movement and fueling the spirit of opposition against the Umayyad authority represented by their wards on Iraq, especially since the Umayyad authority took a repressive policy towards them, which had a clear impact in the emergence of several revolutions that demanded the overthrow of the Umayyad rule and the establishment of a religious state according to the concept of the Koran Constitution. Keywords: Umayyad state, Kharijites, Al-Qa’ada of the Kharijites DOI : 10.7176/HRL/50-04 Publication date: November 30 th 2019 1. Introduction It is known that the Umayyad power in politics against the people of Iraq (Kufa 1 and Basra 2) to the area of the opponent to rule Ali bin Abi Talib (d. 40 AH / 660 AD), so we find that those who were known later Kharidjites and Mu'awiya ibn Abi Sufyan (d. 60 AH / 680 CE), could they be rejecting the Umayyad power? After the emergence of the arbitration case in favor of Muawiya, and disbelieve all who accept the outcome of the arbitration of the general public 3came to be called the first court. -

Arabic Manuscripts

:\ HAXDLIST OF THE Arabic l\Ianuscripts THE CHESTER BEATTY LIBRARY A HANDLIST OF THE Arabic Manuscripts Volu,ne III. MSS. 3501 to 3750 BY AR'THU R ]. ARBERRY LITT. D., F.B.A. Sir Thomas Adams's Professor of Arabic in the University of Cambridge With 3 I plates DUBLIN HODGES, FIGGIS & CO. LTD. 1958 PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN TEXT BY CHARLES BATEY, PRINTER TO THE UNIVERSITY UNIVERSITY PRESS, OXFORD PLATES BY MESSRS. EMERY WALKER, LTD. LONDON DESCRIPTIONS OF MANUSCRIPTS 3501 (1) SHJ'R AL-SHANFARA, by AL-SHANFARA al-Azdi (ft. 6th century A.D.). [Collected poems with a brief anonymous comn1entary; foll. 1-27.] Brockelmann i. 25, Suppl. i. 52-54. (2) SHARIJ QA$1DAT AL-BURDA, by Abu Zakariya' Yal_iya b. 'Ali al-Khatib AL-TIBRIZI (d. 502/1108). [ A commentary on the well-known panegyric of the Prophet Mu}:iammad by KA'B B. ZUHAIR (ft. 1st/7th century); foll. 28-5 5.] DatedJumada I 836 (January 1433). Brockelmann i. 3 9, Sup pl. i. 69. (3) AL-MAQfURAT AL-KUBRA, by IBN DURAID (d. 321/ 934). [ A well-known poem illustrating a point of orthography, with a brief anonymous interlineary commentary; foll. 56-58.] Brockelmann i. 1 12, Sup pl. i. 173. Foll. 60. 18 X 13· 5 cm. Clear scholar's naskh. Copyist, 'Abd al-Karim b. Mu}:iammad al-Shafi'L Dated (fol. 1a)Jumada II 835 (February 1432) and 836 (1433). 3502 (1) AL-MURSHID AL-WAJlZ.ILA'ULUM TATA'ALLAQ BI'L-KITAB AL-'AZlZ, by ABO SHAMA (d. 665/1268). -

Servants at the Gate: Eunuchs at the Court of Al-Muqtadir

JESHO_art 666Cheikh_234-252 5/23/05 4:50 PM Page 234 SERVANTS AT THE GATE: EUNUCHS AT THE COURT OF AL-MUQTADIR BY NADIA MARIA EL-CHEIKH* Abstract This paper investigates the eunuch’s institution in the court of the Abbasid caliph al-Muqtadir and seeks, first, to delineate the variety of functions that the eunuchs held in the early fourth/tenth century Abbasid court both in the harem and in ceremonial; second, it investi- gates the careers of the eunuchs —®f¬ al-ºuram¬ and MufliΩ al-Kh®dim al-Aswad, exploring their sources of authority and their various networks which allowed them to exercise a high degree of political influence. Le but de ce travail est d’étudier l’institution “Eunuque” au coeur de la cour Abbaside du caliphe al-Muqtadir. En premier lieu nous soulignons les fonctions multiples que les eunuques performaient dans la cour abbaside (début 4/10ème siècle) tant au sein du harem pendant le ceremonial royal. En second lieu nous explorons plus en détail les carrières des eunuques —®f¬ al-ºuram¬ et MufliΩ al-Kh®dim al-Aswad, identifiant les sources de leur pou- voir et les réseaux differents qui leur permirent d’éxercer une veritable influence politique. Keywords: eunuchs, court, al-Muqtadir, harem, ceremonial INTRODUCTION In his recent comprehensive work on eunuchs in Islam, David Ayalon tried to show “how the eunuch institution functioned in fact.” He acknowledges that his study can “at best be considered as a skeleton with many bones missing, and others only partly restored.”1 This paper seeks to restore more bone to the skeleton by investigating eunuchs in the early fourth/tenth century, focusing on the nature of their presence and the extent of their power in the court of the Abbasid caliph al-Muqtadir (295-320/908-932). -

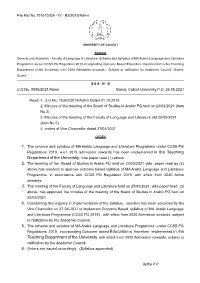

In the Teaching Department of the University, Vide Paper Read (1) Above

File Ref.No.101610/GA - IV - B2/2019/Admn UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT Abstract General and Academic - Faculty of Language & Literature- Scheme and Syllabus of MA Arabic Language and Literature Programme as per CCSS PG Regulation 2019 incorporating Outcome Based Education- Implemented in the Teaching Department of the University w.e.f 2020 Admission onwards - Subject to ratification by Academic Council -Orders Issued. G & A - IV - B U.O.No. 5598/2021/Admn Dated, Calicut University.P.O, 26.05.2021 Read:-1. U.O.No. 15363/2019/Admn Dated 31.10.2019 2. Minutes of the meeting of the Board of Studies in Arabic PG held on 23/02/2021 (Item No 2) 3. Minutes of the meeting of the Faculty of Language and Literature dtd 25/03/2021 (item No 5) 4. orders of Vice Chancellor dated 27/04/2021 ORDER 1. The scheme and syllabus of MA Arabic Language and Literature Programme under CCSS PG Regulations 2019, w.e.f 2019 admission onwards has been implemented in the Teaching Department of the University, vide paper read (1) above. 2. The meeting of the Board of Studies in Arabic PG held on 23/02/2021 vide paper read as (2) above has resolved to approve outcome based syllabus of MA Arabic Language and Literature Programme, in accordance with CCSS PG Regulation 2019, with effect from 2020 Admn onwards. 3. The meeting of the Faculty of Language and Literature held on 25/03/2021, vide paper read (3) above, has approved the minutes of the meeting of the Board of Studies in Arabic PG held on 23/02/2021. -

Voorhoeve, Handlist, Index Personal Names, Part 2

Ibrahim b. Ismä'il Ibn al-Agdäbi Ibrahim b. Ismä'il ag-gaffär al-Bukhäri Ibrahim b.Khälid al -'UlufI (gärim ad-DIn) c. 1147/1734: Su'älät Ibrahim b. Mahmud al-Äqsarä'i al - Mawähibi Ibrahim b. al-Muballit asS-Säfi'i H. 977: v. 'Agä'ib az-zamän IbrähTm b. al-Mufarriq as-gflrl IbrähTm b. Muhammad al-AndalusI IbrähTm b. Muhammad al - Bägürl Ibrahim b. Muhammad al-Baihaqi IbrähTm b. Muhammad al-Gadanfar at-Tibrizi IbrähTm b. Muhammad al -HadawT IbrShTm b. Muhammad al-HalabT Ibrahim b. Muhammad Ibn AbT garif Ibrahim b. Muhammad al-Isfara'ini IbrähTm b. Muhammad al-IstakhrT Ibrahim b. Muhammad al-Maimüru Ibrähfrn b. Muhammad al-Ma'munT IbrähTm b. Muhammad al-QiratT Ibrahim b. Muhammad as -Suhüll IbrähTm b. Sahl al-Isrä'ill IbrähTm b. Sälih al-HindJ IbrähTm b. Särim ad-DIn as-Saidäwi Ibrahim b. 'Umar al-Biqä'I Ibrahim b. 'Umar al-Óa'bari Ibrahim b. Yahyä Ibn az -Zarqäla Ibrahim b. Yüsuf Ibn Qurqül Ibrahim Ibn Hiläl as-Säbi Ibrahim al-KIéi ("Izz ad-Din) Ibrahim al-Laqäni Ibrahim ar-Raqqi Ibrahim ar-Ras"idT; Natigat al-aflcär Ibrahim aä-ääti'l al-Aé'arl asS-SattärT (Faqlh): GamT' al-gawämi' Ibrahim §aläh ad-DTn b. 'Abd Allah H. 1066: Mamlakat sayyid al-kawnain IbrBhTm ae-äämi IbrähTm aä-Sitibi (Abu Ishäq) Ibrahim as -Süfi IbrähTm at-Taiml Ibrahim al-Taqafi al-Ibslhi (Muhammad b. Ahmad) d. c. 850/1446: al-Mustafraf Idris: Du'ä' IdrTsb. Ahmad b.Idrïs a^-Säfi'I: Fatäwi Idris b. Baidukin(?) b. -

The Function of Poetry in the Maqamat Al-Hariri

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2-24-2020 The Function of Poetry in the Maqamat al-Hariri Hussam Almujalli Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Arabic Language and Literature Commons, Arabic Studies Commons, and the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation Almujalli, Hussam, "The Function of Poetry in the Maqamat al-Hariri" (2020). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 5156. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/5156 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE FUNCTION OF POETRY IN THE MAQAMAT AL-HARIRI A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Humanities and Social Sciences College in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Comparative Literature by Hussam Almujalli B.A., Al-Imam Muhammad Ibn Saud Islamic University, 2006 M.A., Brandeis University, 2014 May 2020 Acknowledgments I would like to acknowledge all of the help that the faculty members of the Comparative Literature Department at Louisiana State University have given me during my time there. I am particularly grateful to my advisor, Professor Gregory Stone, and to my committee members, Professor Mark Wagner and Professor Touria Khannous, for their constant help and guidance. This dissertation would not have been possible without the funding support of the Comparative Literature Department at Louisiana State University.