Pdf/5/1/5/919882/5Raengo.Pdf by Guest on 30 September 2021 FIGURE 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

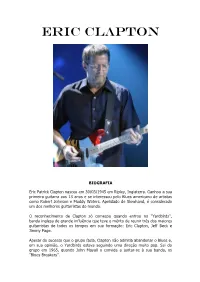

Eric Clapton

ERIC CLAPTON BIOGRAFIA Eric Patrick Clapton nasceu em 30/03/1945 em Ripley, Inglaterra. Ganhou a sua primeira guitarra aos 13 anos e se interessou pelo Blues americano de artistas como Robert Johnson e Muddy Waters. Apelidado de Slowhand, é considerado um dos melhores guitarristas do mundo. O reconhecimento de Clapton só começou quando entrou no “Yardbirds”, banda inglesa de grande influência que teve o mérito de reunir três dos maiores guitarristas de todos os tempos em sua formação: Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck e Jimmy Page. Apesar do sucesso que o grupo fazia, Clapton não admitia abandonar o Blues e, em sua opinião, o Yardbirds estava seguindo uma direção muito pop. Sai do grupo em 1965, quando John Mayall o convida a juntar-se à sua banda, os “Blues Breakers”. Gravam o álbum “Blues Breakers with Eric Clapton”, mas o relacionamento com Mayall não era dos melhores e Clapton deixa o grupo pouco tempo depois. Em 1966, forma os “Cream” com o baixista Jack Bruce e o baterista Ginger Baker. Com a gravação de 4 álbuns (“Fresh Cream”, “Disraeli Gears”, “Wheels Of Fire” e “Goodbye”) e muitos shows em terras norte americanas, os Cream atingiram enorme sucesso e Eric Clapton já era tido como um dos melhores guitarristas da história. A banda separa-se no fim de 1968 devido ao distanciamento entre os membros. Neste mesmo ano, Clapton a convite de seu amigo George Harisson, toca na faixa “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” do White Album dos Beatles. Forma os “Blind Faith” em 1969 com Steve Winwood, Ginger Baker e Rick Grech, que durou por pouco tempo, lançando apenas um album. -

Anansi Boys Neil Gaiman

ANANSI BOYS NEIL GAIMAN ALSO BY NEIL GAIMAN MirrorMask: The Illustrated Film Script of the Motion Picture from The Jim Henson Company(with Dave McKean) The Alchemy of MirrorMask(by Dave McKean; commentary by Neil Gaiman) American Gods Stardust Smoke and Mirrors Neverwhere Good Omens(with Terry Pratchett) FOR YOUNG READERS (illustrated by Dave McKean) MirrorMask(with Dave McKean) The Day I Swapped My Dad for Two Goldfish The Wolves in the Walls Coraline CREDITS Jacket design by Richard Aquan Jacket collage from Getty Images COPYRIGHT Grateful acknowledgment is made for permission to reprint the following copyrighted material: “Some of These Days” used by permission, Jerry Vogel Music Company, Inc. Spider drawing on page 334 © by Neil Gaiman. All rights reserved. This book is a work of fiction. The characters, incidents, and dialogue are drawn from the author’s imagination and are not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to actual events or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental. ANANSI BOYS. Copyright© 2005 by Neil Gaiman. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of PerfectBound™. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gaiman, Neil. -

Bob Ellis at 70 PROFILE from the Bank to the Birdcage

20 12 HONIWeek Eleven October 17 SOIT Senate Results: Writing, women, From the Bank What Senator Pat and wowsers: to the Birdcage: means for you Bob Ellis at 70 Sydney’s drag kings CAMPUS 4 PROFILE 11 FEATURE 12 Contents This Week The Third Drawer SRC Pages 8 Sex, Messages, Reception. 19 Mason McCann roadtests the iPhone 5 The Back Page 23 Presenting the Honi Laureates Spooky Soit for 2012 10 Mariana Podesta-Diverio looks on the bright side of death Editor in Chief: Rosie Marks-Smith Editors: James Alexander, Hannah Bruce, Bebe D’Souza, 11 Profile: Bob Ellis Paul Ellis, Jack Gow, Michael Koziol, James O’Doherty, Michael Koziol talks to one of his Kira Spucys-Tahar, Richard Withers, Connie Ye heroes, Bob Ellis Reporters: Michael Coutts, Fabian Di Lizia, Eleanor Gordon-Smith, Brad Mariano, Virat Nehru, Drag Kings Sean O’Grady, Andrew Passarello, Justin Pen, 12 Lucy Watson walks the streets of Hannah Ryan, Lane Sainty, Lucy Watson, Dan Zwi Newtown to teach us about drag Contributors: Rebecca Allen, Chiarra Dee, John Gooding, kings John Harding-Easson, Joseph Istiphan, Stephanie Langridge, 11 Mason McCann, Mariana Podesta-Diverio, Ben Winsor Culture Vulture 3 Spam 14 Crossword: Paps Dr Phil wrote us a letter! Well, sort of. Where has the real Slim Shady gone? Cover: Angela ‘panz’ Padovan of Panz Photography Asks John Gooding Advertising: Amanda LeMay & Jessica Henderson [email protected] Campus 16 Tech & Online 4 Connie Ye teaches us how to dance Justin Pen runs us through social your PhD media in modern Aussie politics HONISOIT.COM News Review Action-Reaction Disclaimer: 6 17 Honi Soit is published by the Students’ Representative Council, University of Sydney, Level 1 Why are Sydney buses exploding? An open letter to the Australian Rugby Wentworth Building, City Road, University of Sydney, NSW, 2006. -

Icons of Catastrophe: Diagramming Blackness in Until the Quiet Comes

"U NTIL THE Q U IET C OMES” (D IREC TED BY K AHLIL J OSEPH , 2013, WHAT MATTERS MOST/P U LSE FILMS), FRAME GRAB . Kahlil Joseph’s “Until the Quiet leaning to the right, the camera Comes” is a short film about a series pans to an ambulance parked on the of miraculous and catastrophic street. It is possible the emergency Icons of events. The camera moves gracefully vehicle arrived in response to the through a dreamy Los Angeles dancer’s wounds, but now its red Catastrophe: sunset as black children play and, flashing lights illuminate the entire as if it were predestined, die. Then, neighborhood with a warning signal. without warning, bodies begin to Even as the film fades to black—the move gracefully in reverse while editing transition and color that the world around them continues has become cinema’s definitive Diagramming to move forward. Finally, in the last word—this discontinuous dramatic conclusion of the film, a narrative about black bodies remains man bleeding from bullet wounds incomplete and in suspension. Blackness in Until on the ground miraculously rises and begins to dance. He removes The central conceit of “Until the his bloodstained shirt and, evidently, Quiet Comes” is contradiction. The the Quiet Comes the finality of death. Then, he enters film subjects viewers to violence a car and drives off into the night. that is horrific yet beautifully surreal Lauren M. The film moves effortlessly between and to an unending cycle of death Cramer different settings and times, without and vibrancy. Similarly, we see giving viewers a sense of direction, blackness through the contradictory but this stunning possibility for forces that shape it, boundless change (and even reanimation) possibility and crushing confinement. -

Ysu1311869143.Pdf (795.38

THIS IS LIFE: A Love Story of Friendship by Annie Murray Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of M.F.A. in the NEOMFA Program YOUNGSTOWN STATE UNIVERSITY May, 2011 THIS IS LIFE: A Love Story of Friendship Annie Murray I hereby release this thesis to the public. I understand that this thesis will be made available from the OhioLINK ETD Center and the Maag Library Circulation Desk for public access. I also authorize the University or other individuals to make copies of this thesis as needed for scholarly research. Signature: ________________________________________________________ Annie Murray, Student Date Approvals: ________________________________________________________ David Giffels, Thesis Advisor Date ________________________________________________________ Phil Brady, Committee Member Date ________________________________________________________ Mary Biddinger, Committee Member Date ________________________________________________________ Peter J. Kasvinsky, Dean, School of Graduate Studies and Research Date © A. Murray 2011 ABSTRACT This thesis explores the universal journey of self discovery against the specific backdrop of the south coast of England where the narrator, an American woman in her early twenties, lives and works as a barmaid with her female travel companion. Aside from outlining the journey from outsider to insider within a particular cultural context, the thesis seeks to understand the implications of a defining friendship that ultimately fails, the ways a young life is shaped through travel and loss, and the sacrifices a person makes when choosing a place to call home. The thesis follows the narrator from her initial departure for England at the age of twenty-two through to her final return to Ohio at the age of twenty-seven, during which time the friendship with the travel companion is dissolved and the narrator becomes a wife and a mother. -

Sleepers 1996

Rev. 6/6/95 {Blue) Rev. 7/31/95 ("Pin.kl Rev. 8/14/95 {Yellow) Rev. 8/18/95 {Green) Rev'. 8/29/95 {Goldenrod) Rev. 8/30/95 {Buff) SLEEPERS screenplay by Barry Levinson based on the book by Lorenzo Carcaterra April 14, 1995 SCREEN IS BLACK LORENZO'S NARRATION I sat across the table from the man who had battered and tortured and brutalized me nearly thirty years ago. Al FADE IN Al TIGHT SHOT of a MAN'S face in shadow. The room is dimly-lit and we can't make out where we are. MAN I don't know what you want me to s.ay. I didn't mean all those things. None of us did. ADULT SHAKES O/C I don't need you to be sorry. It doesn't do me any good. MAN I'm begging you ... try to forgive me. Please ... try. ADULT SHAKES O/C Lea= to live with it. MAN I can't. Not any more. ADULT SHAKES 0/C Then die with it, just like the rest of us. FADE TO BLACK LORENZO'S NARRATION This is a true story about friendship that runs deeper than blood. FADE UP 1 INT. GYM - EVENING J. * The gym is full of BOYS and GIRLS between the ages of 9 and J.3. They're dancing in a 'twist' competition while a DJ plays records. However, there is no so1md, and the film is slightly slowed down, making the movements a little e'1<:aggerated. LORENZO'S NARRATION This is my story, and that of the only three friends in my life who truly mattered. -

Blasting at the Big Ugly: a Novel Andrew Donal Payton Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2014 Blasting at the Big Ugly: A novel Andrew Donal Payton Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Fine Arts Commons Recommended Citation Payton, Andrew Donal, "Blasting at the Big Ugly: A novel" (2014). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 13745. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/13745 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Blasting at the Big Ugly: A novel by Andrew Payton A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTERS OF FINE ARTS Major: Creative Writing and Environment Program of Study Committee: K.L. Cook, Major Professor Steve Pett Brianna Burke Kimberly Zarecor Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2014 Copyright © Andrew Payton 2014. All rights reserved. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iii ABSTRACT iv INTRODUCTION 1 BLASTING AT THE BIG UGLY 6 BIBLIOGRAPHY 212 VITA 213 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am graciously indebted: To the MFA Program in Creative Writing and Environment at Iowa State, especially my adviser K.L. Cook, who never bothered making the distinction between madness and novel writing and whose help was instrumental in shaping this book; to Steve Pett, who gave much needed advice early on; to my fellow writers-in-arms, especially Chris Wiewiora, Tegan Swanson, Lindsay Tigue, Geetha Iyer, Lindsay D’Andrea, Lydia Melby, Mateal Lovaas, and Logan Adams, who championed and commiserated; to the faculty Mary Swander, Debra Marquart, David Zimmerman, Ben Percy, and Dean Bakopolous for writing wisdom and motivation; and to Brianna Burke and Kimberly Zarecor for invaluable advice at the thesis defense. -

Lauren Cramer

Lauren M. Cramer Curriculum Vitae Department of Film & Screen Studies Pace University 41 Park Row New York, New York 10038 [email protected] PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Sept 2016 - Present Pace University, New York, NY Assistant Professor Film & Screen Studies EDUCATION August 2016 Georgia State University, Atlanta, GA PhD – Communication, Moving Image Studies Dissertation: “A Hip-Hop Joint: Thinking Architecturally About Blackness” Committee: Dr. Alessandra Raengo (Chair); Dr. Jennifer Barker; Dr. Angelo Restivo; Dr. Derek Conrad Murray May 2009 Emory University, Atlanta, GA M.A. – Film Studies May 2007 Villanova University, Villanova, PA B.A. – Communication, Sociology and Africana Studies RESEARCH SPECIALIZATIONS African American Popular Culture Film/Media Studies Architectural Theory/Digital Aesthetics Hip Hop Studies Blackness Visual Culture PUBLICATIONS Peer Reviewed Co-Authored with Alessandra Raengo. “Freeing Black Codes: liquid blackness Plays the Jazz Ensemble.” in "Black Code Studies,” ed. Jessica Marie Johnson and Mark Anthony Neal, special issue, The Black Scholar 47 (Summer 2017). “The Black (Universal) Archive and the Architecture of Black Cinema.” Black Camera 8, no. 1 (Fall 2016). Cramer – Curriculum Vitae 2 “Race at the Interface: Rendering Blackness on WorldStarHipHop.com.” Film Criticism 40, no. 2 (January 2016). doi:10.3998/fc.13761232.0040.205. Book Reviews Invited Review of Pulse of the People: Political Rap Music and Black Politics by Lakeyta M. Bonnette. Journal of African American History 102, (Spring 2016) – Forthcoming -

THE HIP HOP TURN Contemporary Art’S Love Affair with Hip Hop Culture from Manhattan to Dakar

1 Dulcie Abrahams Altass THE HIP HOP TURN Contemporary Art’s Love Affair with Hip Hop Culture from Manhattan to Dakar The Dadaist should be a man who has That” was screened at the Fondation Louis fully understood that one is entitled to Vuitton in Paris and at the Los Angeles County have ideas only if one can transform Museum of Art. Hip hop culture seems to be increasingly present in spaces for contem- them into life – the completely active porary art as key figures from both worlds type, who lives only through action, be- collaborate. Beyond the bombastic improb- cause it holds the possibility of achiev- ability and glamour of their fusion, however, ing knowledge. this recent love affair needs to be understood —Richard Huelsenbeck in a nuanced way. It would be short-sighted to ignore the threat of cultural and financial We are not the PDS, not the democrats, appropriation by a majority white art world of we are the PBS, a new party. a multi-facetted culture that was born within Black and Latino communities of the Bronx, —Positive Black Soul at a gaping distance from the white cubes of Manhattan. In 2013, superstar rapper Jay Z teamed up with performance artist Marina Abramovic to Perhaps the clue to understanding this “hip shoot his music video “Picasso Baby” at Pace hop turn” lays in the fact that more than any Gallery in New York during the run of her “The other musical form or cultural genre of the Artist is Present” retrospective at MoMA. The last century, hip hop has shattered the bar- following year artist Kara Walker guest-curat- riers between art and life, fulfilling the aspi- ed Ruffneck Constructivists at the Institute rations of twentieth century avant-gardism. -

Name Artist Album Track Number Track Count Year Wasted Words

Name Artist Album Track Number Track Count Year Wasted Words Allman Brothers Band Brothers and Sisters 1 7 1973 Ramblin' Man Allman Brothers Band Brothers and Sisters 2 7 1973 Come and Go Blues Allman Brothers Band Brothers and Sisters 3 7 1973 Jelly Jelly Allman Brothers Band Brothers and Sisters 4 7 1973 Southbound Allman Brothers Band Brothers and Sisters 5 7 1973 Jessica Allman Brothers Band Brothers and Sisters 6 7 1973 Pony Boy Allman Brothers Band Brothers and Sisters 7 7 1973 Trouble No More Allman Brothers Band Eat A Peach 1 6 1972 Stand Back Allman Brothers Band Eat A Peach 2 6 1972 One Way Out Allman Brothers Band Eat A Peach 3 6 1972 Melissa Allman Brothers Band Eat A Peach 4 6 1972 Blue Sky Allman Brothers Band Eat A Peach 5 6 1972 Blue Sky Allman Brothers Band Eat A Peach 5 6 1972 Ain't Wastin' Time No More Allman Brothers Band Eat A Peach 6 6 1972 Oklahoma Hills Arlo Guthrie Running Down the Road 1 6 1969 Every Hand in the Land Arlo Guthrie Running Down the Road 2 6 1969 Coming in to Los Angeles Arlo Guthrie Running Down the Road 3 6 1969 Stealin' Arlo Guthrie Running Down the Road 4 6 1969 My Front Pages Arlo Guthrie Running Down the Road 5 6 1969 Running Down the Road Arlo Guthrie Running Down the Road 6 6 1969 I Believe When I Fall in Love Art Garfunkel Breakaway 1 8 1975 My Little Town Art Garfunkel Breakaway 1 8 1975 Ragdoll Art Garfunkel Breakaway 2 8 1975 Breakaway Art Garfunkel Breakaway 3 8 1975 Disney Girls Art Garfunkel Breakaway 4 8 1975 Waters of March Art Garfunkel Breakaway 5 8 1975 I Only Have Eyes for You Art Garfunkel Breakaway 7 8 1975 Lookin' for the Right One Art Garfunkel Breakaway 8 8 1975 My Maria B. -

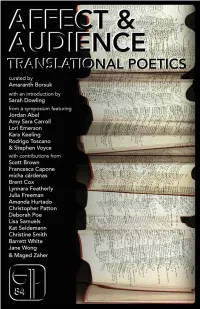

Borsuk Spreads 150.Pdf

AFFECT & AUDIENCE TRANSLATIONAL POETICS curated by AMARANTH BORSUK with an introduction by SARAH DOWLING from a symposium at the University of Washington in January 2016 featuring JORDAN ABEL, AMY SARA CARROLL, LORI EMERSON, KARA KEELING, RODRIGO TOSCANO, & STEPHEN VOYCE with contributions from SCOTT BROWN, FRANCESCA CAPONE, MICHA CÁRDENAS, BRENT COX, LYNNARA FEATHERLY, JULIA FREEMAN, AMANDA HURTADO, CHRISTOPHER PATTON, DEBORAH POE, LISA SAMUELS, KAT SEIDEMANN, CHRISTINE SMITH, BARRETT WHITE, JANE WONG, & MAGED ZAHER #84 ESSAY PRESS LT SERIES CONTENTS In the Essay Press Listening Tour series, we have commissioned some of our favorite conveners of public discussions to curate conversation-based chapbooks. Overhearing such dialogues among poets, prose writers, critics, and artists, we hope Introduction vii to further envision how Essay can emulate by SARAH DOWLING and expand upon recent developments in trans-disciplinary small-press culture. Roundtable Conversation 5 Contributor Bios 59 Series Editors Maria Anderson Andy Fitch Ellen Fogelman Aimee Harrison Courtney Mandryk Victoria A. Sanz Travis A. Sharp Ryan Spooner Series Assistants Cristiana Baik Ryan Ikeda Christopher Liek Emily Pifer Randall Tyrone Cover Image Francesca Capone, Loom of Language Book Design Aimee Harrison INTRODUCTION —Sarah Dowling, Fall 2016 On January 29th, 2016, Amaranth Borsuk (University of Washington, Bothell), micha cárdenas (University of Washington, Bothell), Gregory Laynor (University of Washington, Seattle), Brian Reed (University of Washington, Seattle), and I convened an audience for the one- day symposium Affect & Audience in the Digital Age: Translational Poetics. Building upon a prior conference in 2013, and upon a series of performances and scholarly events during the 2014-2015 academic year, our 2016 symposium sought to investigate contemporary scholarly, aesthetic, and activist projects that engage the processes and thematics of translation. -

From Colorism to Conjurings: Tracing the Dust in Beyoncé's Lemonade Cienna Davis Freie Universitat, Berlin, Germany, [email protected]

Taboo: The Journal of Culture and Education Volume 16 | Issue 2 Article 4 September 2017 From Colorism to Conjurings: Tracing the Dust in Beyoncé's Lemonade Cienna Davis Freie Universitat, Berlin, Germany, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/taboo Recommended Citation Davis, C. (2018). From Colorism to Conjurings: Tracing the Dust in Beyoncé's Lemonade. Taboo: The Journal of Culture and Education, 16 (2). https://doi.org/10.31390/taboo.16.2.04 Taboo,Cienna Fall Davis 2017 7 From Colorism to Conjurings Tracing the Dust in Beyoncé’s Lemonade Cienna Davis Abstract Colorism creates relentless tension and pressure in the lives of Black women. Pop-star Beyoncé Gisele Knowles-Carter is an interesting case in the discussion of colorism because her career has expressed a rich intimacy to Southern Black cul- ture and female empowerment while also playing into tropes of the mulatta “fancy girl,” whose relative proximity to whiteness adheres social value within mainstream culture. Finding aesthetic and thematic parallels between Beyoncé’s recent project Lemonade (2016) and Julie Dash’s cult-classic film Daughters of the Dust (1991) I draw a critical connection between Yellow Mary Peazant and Beyoncé, the prodigal child and the licentious “post-racial,” pop-star to argue that while Lemonade may not present the same critique of exclusionary Black womanhood present within Daughters of the Dust, reactions to the Beyoncé’s visual album and the “Formation” music video inadvertently demonstrate the longevity of harmful colorist prejudices and the disparaging of Black female sexual and creative agency within the Black community.