Inside the Trampoline

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Customer Order Form

#355 | APR18 PREVIEWS world.com ORDERS DUE APR 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Apr18 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 3/8/2018 3:51:03 PM You'll for PREVIEWS!PREVIEWS! STARTING THIS MONTH Toys & Merchandise sections start with the Back Cover! Page M-1 Dynamite Entertainment added to our Premier Comics! Page 251 BOOM! Studios added to our Premier Comics! Page 279 New Manga section! Page 471 Updated Look & Design! Apr18 Previews Flip Ad.indd 1 3/8/2018 9:55:59 AM BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SWORD SLAYER SEASON 12: DAUGHTER #1 THE RECKONING #1 DARK HORSE COMICS DARK HORSE COMICS THE MAN OF JUSTICE LEAGUE #1 THE LEAGUE OF STEEL #1 DC ENTERTAINMENT EXTRAORDINARY DC ENTERTAINMENT GENTLEMEN: THE TEMPEST #1 IDW ENTERTAINMENT THE MAGIC ORDER #1 IMAGE COMICS THE WEATHERMAN #1 IMAGE COMICS CHARLIE’S ANT-MAN & ANGELS #1 BY NIGHT #1 THE WASP #1 DYNAMITE BOOM! STUDIOS MARVEL COMICS ENTERTAINMENT Apr18 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 3/8/2018 3:39:16 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS · GRAPHIC NOVELS · PRINT InSexts Year One HC l AFTERSHOCK COMICS Lost City Explorers #1 l AFTERSHOCK COMICS Carson of Venus: Fear on Four Worlds #1 l AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Archie’s Super Teens vs. Crusaders #1 l ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS Solo: A Star Wars Story: The Official Guide HC l DK PUBLISHING CO The Overstreet Comic Book Price Guide Volume 48 SC/HC l GEMSTONE PUBLISHING Mae Volume 1 TP l LION FORGE 1 A Tale of a Thousand and One Nights: Hasib & The Queen of Serpents HC l NBM Shadow Roads #1 l ONI PRESS INC. -

Eric Clapton

ERIC CLAPTON BIOGRAFIA Eric Patrick Clapton nasceu em 30/03/1945 em Ripley, Inglaterra. Ganhou a sua primeira guitarra aos 13 anos e se interessou pelo Blues americano de artistas como Robert Johnson e Muddy Waters. Apelidado de Slowhand, é considerado um dos melhores guitarristas do mundo. O reconhecimento de Clapton só começou quando entrou no “Yardbirds”, banda inglesa de grande influência que teve o mérito de reunir três dos maiores guitarristas de todos os tempos em sua formação: Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck e Jimmy Page. Apesar do sucesso que o grupo fazia, Clapton não admitia abandonar o Blues e, em sua opinião, o Yardbirds estava seguindo uma direção muito pop. Sai do grupo em 1965, quando John Mayall o convida a juntar-se à sua banda, os “Blues Breakers”. Gravam o álbum “Blues Breakers with Eric Clapton”, mas o relacionamento com Mayall não era dos melhores e Clapton deixa o grupo pouco tempo depois. Em 1966, forma os “Cream” com o baixista Jack Bruce e o baterista Ginger Baker. Com a gravação de 4 álbuns (“Fresh Cream”, “Disraeli Gears”, “Wheels Of Fire” e “Goodbye”) e muitos shows em terras norte americanas, os Cream atingiram enorme sucesso e Eric Clapton já era tido como um dos melhores guitarristas da história. A banda separa-se no fim de 1968 devido ao distanciamento entre os membros. Neste mesmo ano, Clapton a convite de seu amigo George Harisson, toca na faixa “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” do White Album dos Beatles. Forma os “Blind Faith” em 1969 com Steve Winwood, Ginger Baker e Rick Grech, que durou por pouco tempo, lançando apenas um album. -

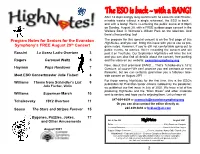

August Highnotes

After 18 depressingly long months with no concerts and 70 inter- minable weeks without a single rehearsal, the ESO is back – and with a bang! We’re re-entering the public arena at 6:00pm on Sunday, August 29, with a FREE outdoor pops concert in the Wallace Bowl in Wilmette’s Gillson Park on the lakefront. And there’s free parking, too! The program for this special concert is on the first page of this Program Notes for Seniors for the Evanston HighNotes, and you can bring this issue with you to use as pro- th Symphony’s FREE August 29 Concert gram notes. However, if you’re still not comfortable going out to public events, no worries. We’re recording the concert and will Rossini La Gazza Ladra Overture 3 post it on YouTube. Our September HighNotes will have the link and you can also find all details about the concert, free parking Rogers Carousel Waltz 5 and the video on our website: evanstonsymphony.org. Now, about that promised BANG!... That’s Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Hayman Pops Hoedown 7 Overture, of course! We can’t promise you real cannons or even fireworks, but we can certainly guarantee you a fabulous lake- Meet ESO Concertmaster Julie Fisher! 8 side concert on August 29th! For those seeing HighNotes for the first time, this is the ESO’s Williams Theme from Schindler’s List 9 publication for Evanston senior citizens isolated by the pandemic; Julie Fischer, Violin we published our first issue in July of 2020. We have a lot of fun producing HighNotes and the “Brain Break” and other materials Williams Superman March 10 sent to seniors, and hope you’re enjoying them. -

Anansi Boys Neil Gaiman

ANANSI BOYS NEIL GAIMAN ALSO BY NEIL GAIMAN MirrorMask: The Illustrated Film Script of the Motion Picture from The Jim Henson Company(with Dave McKean) The Alchemy of MirrorMask(by Dave McKean; commentary by Neil Gaiman) American Gods Stardust Smoke and Mirrors Neverwhere Good Omens(with Terry Pratchett) FOR YOUNG READERS (illustrated by Dave McKean) MirrorMask(with Dave McKean) The Day I Swapped My Dad for Two Goldfish The Wolves in the Walls Coraline CREDITS Jacket design by Richard Aquan Jacket collage from Getty Images COPYRIGHT Grateful acknowledgment is made for permission to reprint the following copyrighted material: “Some of These Days” used by permission, Jerry Vogel Music Company, Inc. Spider drawing on page 334 © by Neil Gaiman. All rights reserved. This book is a work of fiction. The characters, incidents, and dialogue are drawn from the author’s imagination and are not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to actual events or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental. ANANSI BOYS. Copyright© 2005 by Neil Gaiman. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of PerfectBound™. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gaiman, Neil. -

Ysu1311869143.Pdf (795.38

THIS IS LIFE: A Love Story of Friendship by Annie Murray Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of M.F.A. in the NEOMFA Program YOUNGSTOWN STATE UNIVERSITY May, 2011 THIS IS LIFE: A Love Story of Friendship Annie Murray I hereby release this thesis to the public. I understand that this thesis will be made available from the OhioLINK ETD Center and the Maag Library Circulation Desk for public access. I also authorize the University or other individuals to make copies of this thesis as needed for scholarly research. Signature: ________________________________________________________ Annie Murray, Student Date Approvals: ________________________________________________________ David Giffels, Thesis Advisor Date ________________________________________________________ Phil Brady, Committee Member Date ________________________________________________________ Mary Biddinger, Committee Member Date ________________________________________________________ Peter J. Kasvinsky, Dean, School of Graduate Studies and Research Date © A. Murray 2011 ABSTRACT This thesis explores the universal journey of self discovery against the specific backdrop of the south coast of England where the narrator, an American woman in her early twenties, lives and works as a barmaid with her female travel companion. Aside from outlining the journey from outsider to insider within a particular cultural context, the thesis seeks to understand the implications of a defining friendship that ultimately fails, the ways a young life is shaped through travel and loss, and the sacrifices a person makes when choosing a place to call home. The thesis follows the narrator from her initial departure for England at the age of twenty-two through to her final return to Ohio at the age of twenty-seven, during which time the friendship with the travel companion is dissolved and the narrator becomes a wife and a mother. -

Sleepers 1996

Rev. 6/6/95 {Blue) Rev. 7/31/95 ("Pin.kl Rev. 8/14/95 {Yellow) Rev. 8/18/95 {Green) Rev'. 8/29/95 {Goldenrod) Rev. 8/30/95 {Buff) SLEEPERS screenplay by Barry Levinson based on the book by Lorenzo Carcaterra April 14, 1995 SCREEN IS BLACK LORENZO'S NARRATION I sat across the table from the man who had battered and tortured and brutalized me nearly thirty years ago. Al FADE IN Al TIGHT SHOT of a MAN'S face in shadow. The room is dimly-lit and we can't make out where we are. MAN I don't know what you want me to s.ay. I didn't mean all those things. None of us did. ADULT SHAKES O/C I don't need you to be sorry. It doesn't do me any good. MAN I'm begging you ... try to forgive me. Please ... try. ADULT SHAKES O/C Lea= to live with it. MAN I can't. Not any more. ADULT SHAKES 0/C Then die with it, just like the rest of us. FADE TO BLACK LORENZO'S NARRATION This is a true story about friendship that runs deeper than blood. FADE UP 1 INT. GYM - EVENING J. * The gym is full of BOYS and GIRLS between the ages of 9 and J.3. They're dancing in a 'twist' competition while a DJ plays records. However, there is no so1md, and the film is slightly slowed down, making the movements a little e'1<:aggerated. LORENZO'S NARRATION This is my story, and that of the only three friends in my life who truly mattered. -

Blasting at the Big Ugly: a Novel Andrew Donal Payton Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2014 Blasting at the Big Ugly: A novel Andrew Donal Payton Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Fine Arts Commons Recommended Citation Payton, Andrew Donal, "Blasting at the Big Ugly: A novel" (2014). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 13745. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/13745 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Blasting at the Big Ugly: A novel by Andrew Payton A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTERS OF FINE ARTS Major: Creative Writing and Environment Program of Study Committee: K.L. Cook, Major Professor Steve Pett Brianna Burke Kimberly Zarecor Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2014 Copyright © Andrew Payton 2014. All rights reserved. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iii ABSTRACT iv INTRODUCTION 1 BLASTING AT THE BIG UGLY 6 BIBLIOGRAPHY 212 VITA 213 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am graciously indebted: To the MFA Program in Creative Writing and Environment at Iowa State, especially my adviser K.L. Cook, who never bothered making the distinction between madness and novel writing and whose help was instrumental in shaping this book; to Steve Pett, who gave much needed advice early on; to my fellow writers-in-arms, especially Chris Wiewiora, Tegan Swanson, Lindsay Tigue, Geetha Iyer, Lindsay D’Andrea, Lydia Melby, Mateal Lovaas, and Logan Adams, who championed and commiserated; to the faculty Mary Swander, Debra Marquart, David Zimmerman, Ben Percy, and Dean Bakopolous for writing wisdom and motivation; and to Brianna Burke and Kimberly Zarecor for invaluable advice at the thesis defense. -

![Effects of Wind Farms on the Nest Distribution of Magpie (Pica Pica) ]] in Agroforestry Systems of Chongming Island, China ]]]]]]]]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0078/effects-of-wind-farms-on-the-nest-distribution-of-magpie-pica-pica-in-agroforestry-systems-of-chongming-island-china-1440078.webp)

Effects of Wind Farms on the Nest Distribution of Magpie (Pica Pica) ]] in Agroforestry Systems of Chongming Island, China ]]]]]]]]

Global Ecology and Conservation 27 (2021) e01536 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Global Ecology and Conservation journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/gecco Effects of wind farms on the nest distribution of magpie (Pica pica) ]] in agroforestry systems of Chongming Island, China ]]]]]]]] Ningning Songa, Huan Xua, Shanshan Zhaoa, Ningning Liua, Shurong Zhonga, Ben Lia,c,⁎, Tianhou Wanga,b,⁎ a School of Life Science, East China Normal University, Shanghai 200062, China b Institute of Eco-Chongming, Shanghai 202162, China c Shanghai Key Lab for Urban Ecological Processes and Eco-Restoration, Shanghai 200241, China article info abstract Article history: The use of wind turbines for energy generation has complex impacts on ecosystems, espe Received 11 January 2021 cially for flying wildlife. Given the importance of birds in many ecosystems and food webs, Received in revised form 4 March 2021 they are often used as ecological indicators to evaluate the direct (e.g., collision mortality) Accepted 5 March 2021 and indirect (e.g., habitat degradation and loss, low food available) impact of wind farms. To test the effect of wind farms on the nest distribution of magpie (Pica pica), a common bird Keywords: species in agroforestry systems on Chongming Island, China, the differences in magpie nest Magpie Nest density variables density variables and character variables were compared between quadrats inside and Nest character outside a wind farm. The relationship between magpie nest character variables and density Wind farm variables in each quadrat was also examined and the impacts of landscape variables on Landscape magpie nest density variables were clarified in each quadrat. From March to December 2019, nest density variables (including total and in-use nest density) were recorded in quadrats inside and outside a wind farm in an agroforestry system on Chongming Island, Shanghai. -

By Rasmuson Foundation by Kyle Clayton Across Southeast Alaska and the Wayne Price Was Honored Yukon

Assembly discusses EOC pay - page 2 Large cruise line courts Haines - page 3 Serving Haines and Klukwan, Alaska since 1966 Volume LIV, Issue 17 Thursday, April 30, 2020 $1.25 State relaxes mandates, some remain cautious As oil prices By Kyle Clayton Injury Disaster Loan Emergency While some local business owners Advance because she has no crash, residents are expanding operations since the employees, and she was turned state’s “Reopen Alaska Responsibly” away from applying for a Paycheck question high plan began Friday, some are reluctant Protection Program (PPP) loan to open their doors. In the midst because First National Bank Alaska is of reopening, some businesses are currently not accepting applications pump prices unable to apply for federal relief for that program. By Kyle Clayton loans and are reeling from the loss She said she’ll have to drum up Oil prices began to plummet in of revenue. local support and find additional mid-February due to the COVID-19 The state released a health mandate revenue streams. She said she is worldwide pandemic and economic last week that loosened restrictions planning on renting out a part of her downturn and bottomed out around on retail businesses, restaurants, building to another business. April 21. Haines gas prices are still personal care services, fishing First National Bank Alaska Haines higher than most communities across charters and other non-essential branch manager Wendell Harren the region, which has befuddled some businesses. said the bank is no longer accepting Haines residents. The Magpie Gallery owner Laura applications because they’re still “A barrel of oil costs 12 bucks, but Rogers has three children who can’t processing an “unprecedented not if you go to Delta Western,” Fred go to school and her husband, Manuel, amount and continue to process Shields quipped this week. -

Tattersalls Catalogue Page

THE PROPERTY OF MR. PATRICK A. O'BRIEN LOT 1 1 Kenmare Highest Honor Take Risks (FR) High River Be My Guest BAY MARE (FR) Baino Bluff Rapids (2005) Petong (Third Produce) Chateau Lina (IRE) Paris House Foudroyer (1997) General Assembly Talina Cyriana This mare is broken. Guaranteed untried. Sold with Veterinary Certificate. (See Conditions of Sale). 1st dam CHATEAU LINA (IRE): 2 wins at 2 and 3 years and £7854; dam of 2 winners from 3 runners and 7 foals; Legal Spirit (IRE) (2003 c. by Even Top (IRE)): 6 wins at 3 and 6 years, 2009 in Greece and £42,235 and placed 13 times. Sand Castle (FR) (2007 c. by Marchand de Sable (USA)): winner at 3 years, 2010 in France and £6991 and placed 3 times. Topo Gigio (FR) (2004 g. by Even Top (IRE)): placed once over hurdles at 5 years, 2009 and placed once over fences at 6 years, 2010. Chateau de Cartes (FR) (2006 g. by Martaline (GB)): unraced to date. Art House (FR) (2009 c. by Definite Article (GB)). 2nd dam TALINA: 3 wins at 3 years in France; dam of 3 winners from 5 runners and 5 foals inc.: TALINA'S LAW (IRE) (f. by Law Society (USA)): 4 wins, £26,180: winner at 4 years and placed twice; also 3 wins over hurdles at 4 years and £21,901 inc. RTE Spring Juvenile Hurdle, Leopardstown, L. and Murphys Irish Stout Juvenile Hurdle, Punchestown, L., placed 4 times; dam of 6 winners inc.: MAJESTIC CONCORDE (IRE): 9 wins, £242,618: 4 wins at 3 and 5 years and placed 6 times; also 2 wins over hurdles at 4 years and placed 3 times inc. -

Name Artist Album Track Number Track Count Year Wasted Words

Name Artist Album Track Number Track Count Year Wasted Words Allman Brothers Band Brothers and Sisters 1 7 1973 Ramblin' Man Allman Brothers Band Brothers and Sisters 2 7 1973 Come and Go Blues Allman Brothers Band Brothers and Sisters 3 7 1973 Jelly Jelly Allman Brothers Band Brothers and Sisters 4 7 1973 Southbound Allman Brothers Band Brothers and Sisters 5 7 1973 Jessica Allman Brothers Band Brothers and Sisters 6 7 1973 Pony Boy Allman Brothers Band Brothers and Sisters 7 7 1973 Trouble No More Allman Brothers Band Eat A Peach 1 6 1972 Stand Back Allman Brothers Band Eat A Peach 2 6 1972 One Way Out Allman Brothers Band Eat A Peach 3 6 1972 Melissa Allman Brothers Band Eat A Peach 4 6 1972 Blue Sky Allman Brothers Band Eat A Peach 5 6 1972 Blue Sky Allman Brothers Band Eat A Peach 5 6 1972 Ain't Wastin' Time No More Allman Brothers Band Eat A Peach 6 6 1972 Oklahoma Hills Arlo Guthrie Running Down the Road 1 6 1969 Every Hand in the Land Arlo Guthrie Running Down the Road 2 6 1969 Coming in to Los Angeles Arlo Guthrie Running Down the Road 3 6 1969 Stealin' Arlo Guthrie Running Down the Road 4 6 1969 My Front Pages Arlo Guthrie Running Down the Road 5 6 1969 Running Down the Road Arlo Guthrie Running Down the Road 6 6 1969 I Believe When I Fall in Love Art Garfunkel Breakaway 1 8 1975 My Little Town Art Garfunkel Breakaway 1 8 1975 Ragdoll Art Garfunkel Breakaway 2 8 1975 Breakaway Art Garfunkel Breakaway 3 8 1975 Disney Girls Art Garfunkel Breakaway 4 8 1975 Waters of March Art Garfunkel Breakaway 5 8 1975 I Only Have Eyes for You Art Garfunkel Breakaway 7 8 1975 Lookin' for the Right One Art Garfunkel Breakaway 8 8 1975 My Maria B. -

Preowned 1970S Sheet Music

Preowned 1970s Sheet Music. PLEASE NOTE THE FOLLOWING FOR CONDITION AND PRICES PER TITLE ex No marks or deteriation Priced £15. good As appropriate for age of the manuscript. Slight marks on front cover (shop stamp or owner's name). Possible slight marking (pencil) inside. Priced £12. fair Some damage such as edging tears. Reasonable for age of manuscript. Priced £5 Album Contains several songs and photographs of the artist(s). Priced £15+ condition considered.. Year Year of print. Usually the same year as copyright (c) but not always. Photo Artist(s) photograph on front cover. n/a No artist photo on front cover LOOKING FOR THESE ARTISTS? You’ve come to the right place for The Bee Gees, Eric Clapton, Russ Conway, John B.Sebastian, Status Quo or even “Woodstock”. Just look for the artist’s name on the lists below. Email us if the title you’re looking for, isn’t here. We may still be able to get it for you. STAMP OUT FORGERIES. Although we take every reasonable precaution to ensure that the items we have for sale are genuine and from the period described, we urge buyers to verify purchases from us and bring to our attention any item discovered to be fake or falsely described. The public can thus be warned and the buyer recompensed. Your cooperation is appreciated. 1970s Title Writer and composer condition Photo year Abba Greatest Hits 19 songs B.Andersson/B.Ulvaeus album Abba © 1992 After the goldrush Neil Young ex Prelude 1970 Albertross Peter Green fair Fleetwood Mac 1970 Albertross (piano solo) Peter Green ex n/a © 1970 All around