Countering Militancy and Terrorism in Pakistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Al Shabaab's American Recruits

Al Shabaab’s American Recruits Updated: February, 2015 A wave of Americans traveling to Somalia to fight with Al Shabaab, an Al Qaeda-linked terrorist group, was described by the FBI as one of the "highest priorities in anti-terrorism." Americans began traveling to Somalia to join Al Shabaab in 2007, around the time the group stepped up its insurgency against Somalia's transitional government and its Ethiopian supporters, who have since withdrawn. At least 50 U.S. citizens and permanent residents are believed to have joined or attempted to join or aid the group since that time. The number of Americans joining Al Shabaab began to decline in 2012, and by 2014, the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) replaced Al Shabaab as the terrorist group of choice for U.S. recruits. However, there continue to be new cases of Americans attempting to join or aid Al Shabaab. These Americans have received weapons training alongside recruits from other countries, including Britain, Australia, Sweden and Canada, and have used the training to fight against Ethiopian forces, African Union troops and the internationally-supported Transitional Federal Government in Somalia, according to court documents. Most of the American men training with Al Shabaab are believed to have been radicalized in the U.S., especially in Minneapolis, according to U.S. officials. The FBI alleges that these young men have been recruited by Al Shabaab both on the Internet and in person. One such recruit from Minneapolis, 22-year-old Abidsalan Hussein Ali, was one of two suicide bombers who attacked African Union troops on October 29, 2011. -

The Parallax View: How Conspiracy Theories and Belief in Conspiracy Shape American Politics

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2020 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2020 The Parallax View: How Conspiracy Theories and Belief in Conspiracy Shape American Politics Liam Edward Shaffer Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2020 Part of the American Politics Commons, and the Political History Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Shaffer, Liam Edward, "The Parallax View: How Conspiracy Theories and Belief in Conspiracy Shape American Politics" (2020). Senior Projects Spring 2020. 236. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2020/236 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Parallax View: How Conspiracy Theories and Belief in Conspiracy Shape American Politics Senior Project Submitted to The Division of Social Studies of Bard College by Liam Edward Shaffer Annandale-on-Hudson, New York May 2020 Acknowledgements To Simon Gilhooley, thank you for your insight and perspective, for providing me the latitude to pursue the project I envisioned, for guiding me back when I would wander, for keeping me centered in an evolving work and through a chaotic time. -

Pakistan: Death Plot Against Human Rights Lawyer, Asma Jahangir

UA: 164/12 Index: ASA 33/008/2012 Pakistan Date: 7 June 2012 URGENT ACTION DEATH PLOT AGAINST HUMAN RIGHTS LAWYER Leading human rights lawyer and activist Asma Jahangir fears for her life, having just learned of a plot by Pakistan’s security forces to kill her. Killings of human rights defenders have increased over the last year, many of which implicate Pakistan’s Inter- Service Intelligence agency (ISI). On 4 June, the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) alerted Amnesty International to information it had received of a plot by Pakistan’s security forces to kill HRCP founder and human rights lawyer Asma Jahangir. As Pakistan’s leading human rights defender, Asma Jahangir has been threatened many times before. However news of the plot to kill her is altogether different. The information available does not appear to have been intentionally circulated as means of intimidation, but leaked from within Pakistan’s security apparatus. Because of this, Asma Jahangir believes the information is highly credible and has therefore not moved from her home. Please write immediately in English, Urdu, or your own language, calling on the Pakistan authorities to: Immediately provide effective security to Asma Jahangir. Promptly conduct a full investigation into alleged plot to kill her, including all individuals and institutions suspected of being involved, including the Inter-Services Intelligence agency. Bring to justice all suspected perpetrators of attacks on human rights defenders, in trials that meet international fair trial standards and -

Equatorial Guinea | Freedom House

Equatorial Guinea | Freedom House https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2019/equatorial-guinea A. ELECTORAL PROCESS: 0 / 12 A1. Was the current head of government or other chief national authority elected through free and fair elections? 0 / 4 President Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo, Africa’s longest-serving head of state, has held power since 1979. He was awarded a new seven-year term in the April 2016 presidential election, reportedly winning 93.5 percent of the vote. The main opposition party at the time, Convergence for Social Democracy (CPDS), boycotted the election, and other factions faced police violence, detentions, and torture. One opposition figure who had been barred from running for president, Gabriel Nsé Obiang Obono, was put under house arrest during the election, and police used live ammunition against supporters gathered at his home. A2. Were the current national legislative representatives elected through free and fair elections? 0 / 4 The bicameral parliament consists of a 70-seat Senate and a 100-seat Chamber of Deputies, with members of both chambers serving five-year terms. Fifteen senators are appointed by the president, 55 are directly elected, and there can be several additional ex officio members. The Chamber of Deputies is directly elected. In the November 2017 legislative elections, the ruling Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea (PDGE) and its subordinate allied parties won 99 seats in the lower house, all 55 of the elected seats in the Senate, and control of all municipal councils. The opposition CI, led by Nsé Obiang, took a single seat in the Chamber of Deputies and a seat on the capital’s city council. -

Crisis Response Bulletin Page 1-16

IDP IDP IDP CRISIS RESPONSE BULLETIN April 06, 2015 - Volume: 1, Issue: 12 IN THIS BULLETIN HIGHLIGHTS: English News 3-29 Punjab to help Sindh computerise land record 03 Three more killed as heavy rain, Hailstones continue to Hit Sindh 03 48,076 Rescued by 1122 in One Month 05 Natural Calamities Section 3-8 NDMA issues flood warning for areas in Punjab 06 Safety and Security Section 9-14 Curbing terrorism:Counter-terror stations to start probes in two weeks 09 Police gear up for Easter Day protection against terrorism 09 Public Services Section 15-29 No country for old Afghans: ‘Post-1951 immigrants to be considered 10 illegal’ Maps 30-36 WB extends financial help of $75m to Fata TDPs 11 Free the streets: SHC orders law enforcers to continue action against 11 barriers Urdu News 50-37 AJK to expel 11,000 Afghans; bans 63 outfits in the region 12 IDPs’ return to North Waziristan begins 13 Natural Calamities Section 50-48 Ranking of Pakistan in education 15 Scheduled and unscheduled load shedding increases in Lahore 17 Safety and Security section 47-43 Power shortfall decreases to 3,400MW 18 Public Service Section 42-37 New cybercrime bill tough on individuals’ rights, soft on crime 19 PAKISTAN WEATHER MAP WIND SPEED MAP OF PAKISTAN TEMPERATURE MAP OF PAKISTAN PUNJAB - FIRE INCIDENTS MAP MAPS CNG SECTOR GAS LOAD MANAGEMENT PLAN-SINDH VEGETATION ANALYSIS MAP OF PAKISTAN REGISTERED AND UNREGISTERED MADRASA IN SINDH 70°0'0"E REGISTERED AND UNREGISTERED MADRASA IN SINDH Legend Number of Registered & KARACHI: Twenty per cent of the seminaries functioning Unregistered Madrasa across the province are situated in Karachi west district alone, it emerged on Friday as the home department Registered carried out an exercise aimed at establishing a database 35 Kashmore of madressahs and streamlining their registration Balochistan 54 Punjab process. -

Narendra Modi Takes Oath As Prime Minister of India for the Second Term

# 1 Indian American Weekly: Since 2006 VOL 13 ISSUE 22 ● NEW YORK / DALLAS ● MAY 31 - JUNE 06, 2019 ● ENQUIRIES: 646-247-9458 www.theindianpanorama.news IAF chief Dhanoa is new chairman of chiefs Narendra Modi Takes Oath as Prime of staff committee Minister of India for the Second Term Amit Shah inducted into Cabinet 36 ministers sworn in for a second term 20 MPs take oath of office as cabinet ministers for the first time 24 cabinet ministers, ministers of state sworn in Nine sworn in as MoS (Independent charge) Air Chief Marshal B S Dhanoa on Wednesday , May 29, received the baton Smriti Irani, 5 other women in Modi government of Chairman of Chiefs of Staff Committee from outgoing Navy Chief Admiral Sunil NEW DELHI (TIP): Narendra Modi Lanba who retires on May 31. took oath of office and secrecy as the NEW DELHI (TIP): "Air Chief Prime Minister of India for a second Marshal Birender Singh Dhanoa will consecutive term amid thunderous be the Chairman COSC with effect applause from a select gathering in the from May 31 consequent to sprawling forecourt of the Rashtrapati relinquishment of charge by Bhavan, May 30th evening. Admiral Sunil Lanba upon President Ram Nath Kovind superannuation," a Defense ministry administered the oath to Modi, 24 spokesperson said. Cabinet colleagues, nine Ministers of The Chairman of Chiefs of Staff State (Independent Charge) and 24 Committee is tasked with ensuring Ministers of State. The loudest cheer synergy among the three services was reserved for BJP chief Amit Shah, and evolve common strategy to deal whose induction means the party will with external security challenges have to elect a new president. -

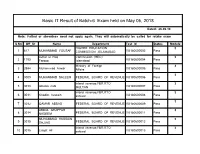

Basic IT Result of Batch-6 Exam Held on May 05, 2018

Basic IT Result of Batch-6 Exam held on May 05, 2018 Dated: 26-06-18 Note: Failled or absentees need not apply again. They will automatically be called for retake exam S.No Off_Sr Name Department Test Id Status Module HIGHER EDUCATION 3 1 617 MUHAMMAD YOUSAF COMMISSION ,ISLAMABAD VU180600002 Pass Azhar ul Haq Commission (HEC) 3 2 1795 Farooq Islamabad VU180600004 Pass Ministry of Foreign 3 3 2994 Muhammad Anwar Affairs VU180600005 Pass 3 4 3009 MUHAMMAD SALEEM FEDERAL BOARD OF REVENUE VU180600006 Pass inland revenue,FBR,RTO 3 5 3010 Ghulan nabi MULTAN VU180600007 Pass inland revenue,FBR,RTO 3 6 3011 Khadim hussain sahiwal VU180600008 Pass 3 7 3012 QAMAR ABBAS FEDERAL BOARD OF REVENUE VU180600009 Pass ABDUL GHAFFAR 3 8 3014 NADEEM FEDERAL BOARD OF REVENUE VU180600011 Pass MUHAMMAD HUSSAIN 3 9 3015 SAJJAD FEDERAL BOARD OF REVENUE VU180600012 Pass inland revenue,FBR,RTO 3 10 3016 Liaqat Ali sahiwal VU180600013 Pass inland revenue,FBR,RTO 3 11 3017 Tariq javed sahiwal VU180600014 Pass 3 12 3018 AFTAB AHMAD FEDERAL BOARD OF REVENUE VU180600015 Pass Basic IT Result of Batch-6 Exam held on May 05, 2018 Dated: 26-06-18 Muhammad inam-ul- inland revenue,FBR,RTO 3 13 3019 haq MULTAN VU180600016 Pass Ministry of Defense (Defense Division) 3 Rawalpindi. 14 4411 Asif Mehmood VU180600018 Pass 3 15 4631 Rooh ul Amin Pakistan Air Force VU180600022 Pass Finance/Income Tax 3 16 4634 Hammad Qureshi Department VU180600025 Pass Federal Board Of Revenue 3 17 4635 Arshad Ali Regional Tax-II VU180600026 Pass 3 18 4637 Muhammad Usman Federal Board Of Revenue VU180600027 -

(1) Government of Pakistan Pakistan Meteorological Department Headquarters Office, Sector H-8/2 P. O. Box No. 1214, Islamabad

GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTAN PAKISTAN METEOROLOGICAL DEPARTMENT HEADQUARTERS OFFICE, SECTOR H-8/2 P. O. BOX NO. 1214, ISLAMABAD PROVISIONAL SENIORITY LIST OF METEOROLOGICAL ASSISTANT (BS-14) AS ON 30-10-2019 S. Name & Qualification Direct/ Domicile Date of Date of Date of Place of Posting Remarks Promotee Birth Entry in Entry in No Govt. Present . Service Scale (BS- 14) M/s. 1. Jawaid Iqbal, B. Sc., M. A. Promotee Sindh (U) 01-06-1961 07-08-1985 08-01-2014 IMG, Karachi. Merged from Prof. Assnt (BS-13) 2. Mazhar Ahmed Siddiqi, M.Sc. Promotee Sindh (U) 13-09-1969 26-11-1988 08-01-2014 RMC, Karachi Merged from Prof. Assnt (BS-13) 3. Sial-Ur-Rehman, B.Sc. Promotee K.P.K 11-02-1968 28-11-1987 08-01-2014 RMC, Peshawar Merged from Prof. Assnt (BS-13) 4. Syed M. Sajjad Raza, B.Sc. Promotee Punjab 13-03-1965 10-08-1986 08-01-2014 RMC, Karachi Merged from Prof. Assnt (BS-13) 5. Muhammad Tahir Shahzad Promotee Punjab 07-03-1970 06-06-1995 08-01-2014 Met. Office, Multan Merged from Prof. Assnt (BS-13) Bhatti, M.Sc. 6. Arshad Ali, M.Sc. Promotee Punjab 10-09-1970 13-11-1989 08-01-2014 Met. Office, Karachi Merged from Prof. Assnt (BS-13) Airport 7. Malik Zahid Mahmood, B. Sc. Promotee Punjab 03-04-1969 15-11-1989 08-01-2014 RCDPC, RMC, Merged from Prof. Assnt (BS-13) Lahore. 8. Ijaz Hussain, M Sc. Promotee Punjab 11-11-1968 05-06-1995 08-01-2014 Met.Obsy. -

Pakistan's Military Elite Paul Staniland University of Chicago Paul

Pakistan’s Military Elite Paul Staniland University of Chicago [email protected] Adnan Naseemullah King’s College London [email protected] Ahsan Butt George Mason University [email protected] DRAFT December 2017 Abstract: Pakistan’s Army is a very politically important organization. Yet its opacity has hindered academic research. We use open sources to construct unique new data on the backgrounds, careers, and post-retirement activities of post-1971 Corps Commanders and Directors-General of Inter-Services Intelligence. We provide evidence of bureaucratic predictability and professionalism while officers are in service. After retirement, we show little involvement in electoral politics but extensive involvement in military-linked corporations, state employment, and other positions of influence. This combination provides Pakistan’s military with an unusual blend of professional discipline internally and political power externally - even when not directly holding power. Acknowledgments: Michael Albertus, Jason Brownlee, Christopher Clary, Hamid Hussain, Sana Jaffrey, Mashail Malik, Asfandyar Mir, Vipin Narang, Dan Slater, and seminar participants at the University of Texas at Austin have provided valuable advice and feedback. Extraordinary research assistance was provided by Yusuf al-Jarani and Eyal Hanfling. 2 This paper examines the inner workings of Pakistan’s army, an organization central to questions of local, regional, and global stability. We investigate the organizational politics of the Pakistan Army using unique individual-level -

PAKISTAN NEWS DIGEST a Selected Summary of News, Views and Trends from Pakistani Media

February 2017 PAKISTAN NEWS DIGEST A Selected Summary of News, Views and Trends from Pakistani Media Prepared by Dr Ashish Shukla & Nazir Ahmed (Research Assistants, Pakistan Project, IDSA) PAKISTAN NEWS DIGEST FEBRUARY 2017 A Select Summary of News, Views and Trends from the Pakistani Media Prepared by Dr Ashish Shukla & Nazir Ahmed (Pak-Digest, IDSA) INSTITUTE FOR DEFENCE STUDIES AND ANALYSES 1-Development Enclave, Near USI Delhi Cantonment, New Delhi-110010 Pakistan News Digest, February (1-15) 2017 PAKISTAN NEWS DIGEST, FEBRUARY 2017 CONTENTS ....................................................................................................................................... 0 ABBREVIATIONS ..................................................................................................... 2 POLITICAL DEVELOPMENTS ............................................................................. 3 NATIONAL POLITICS ....................................................................................... 3 THE PANAMA PAPERS .................................................................................... 7 PROVINCIAL POLITICS .................................................................................... 8 EDITORIALS AND OPINION .......................................................................... 9 FOREIGN POLICY ............................................................................................ 11 EDITORIALS AND OPINION ........................................................................ 12 MILITARY AFFAIRS ............................................................................................. -

Newsletter – April 2008

Newsletter – April 2008 Syed Yousaf Raza Gillani sworn in as Hon. Dr Fahmida Mirza takes her seat th 24 Prime Minister of Pakistan as Pakistan’s first woman Speaker On 24 March Syed Yousaf A former doctor made history Raza Gillani was elected in Pakistan on 19 March by as the Leader of the becoming the first woman to House by the National be elected Speaker in the Assembly of Pakistan and National Assembly of the next day he was Pakistan. Fahmida Mirza won sworn in as the 24th 249 votes in the 342-seat Lower House of parliament. Prime Minister of Pakistan. “I am honoured and humbled; this chair carries a big Born on 9 June 1952 in responsibility. I am feeling that responsibility today and Karachi, Gillani hails from will, God willing, come up to expectations.” Multan in southern Punjab and belongs to a As Speaker, she is second in the line of succession to prominent political family. His grandfather and the President and occupies fourth position in the Warrant grand-uncles joined the All India Muslim League of Precedence, after the President, the Prime Minister and were signatories of the historical Pakistan and the Chairman of Senate. Resolution passed on 23 March 1940. Mr Gillani’s father, Alamdar Hussain Gillani served as a Elected three times to parliament, she is one of the few Provincial Minister in the 1950s. women to have been voted in on a general seat rather than one reserved for women. Mr Yousaf Raza Gillani joined politics at the national level in 1978 when he became a member Fahmida Mirza 51, hails from Badin in Sindh and has of the Muslim League’s central leadership. -

Office of the Governor

SUBJECT: POLITICAL SCIENCE IV TEACHER: MS. DEEPIKA GAHATRAJ MODULE: XI, GOVERNOR: POWERS, FUNCTIONS AND POSITION Topic: Office of the Governor GOVERNOR The Constitution of India envisages the same pattern of government in the states as that for the Centre, that is, a parliamentary system. Part VI of the Constitution, which deals with the government in the states. Articles 153 to 167 in Part VI of the Constitution deal with the state executive. The state executive consists of the governor, the chief minister, the council of ministers and the advocate general of the state. Thus, there is no office of vice-governor (in the state) like that of Vice-President at the Centre. The governor is the chief executive head of the state. But, like the president, he is a nominal executive head (titular or constitutional head). The governor also acts as an agent of the central government. Therefore, the office of governor has a dual role. Usually, there is a governor for each state, but the 7th Constitutional Amendment Act of 1956 facilitated the appointment of the same person as a governor for two or more states. APPOINTMENT OF GOVERNOR The governor is neither directly elected by the people nor indirectly elected by a specially constituted electoral college as is the case with the president. He is appointed by the president by warrant under his hand and seal. In a way, he is a nominee of the Central government. But, as held by the Supreme Court in 1979, the office of governor of a state is not an employment under the Central government.