Migration, Racial Discrimination and Promoting Equality in Cyprus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Sport and Physical Activity Policy for the Republic of Mauritius

NATIONAL SPORT AND PHYSICAL ACTIVITY POLICY FOR THE REPUBLIC OF MAURITIUS 2018-2028 A NEW VISION FOR COMMUNITY SPORT IN MAURITIUS HEALTHIER CITIZENS, HAPPIER COMMUNITIES AND A STRONGER NATION BANN SITWAYIN AN MEYER SANTE, BANN KOMINOTE PLI ERE, ENN NASION PLI FOR A NEW VISION FOR ELITE SPORT IN MAURITIUS INSPIRE MAURITIANS IN THE PURSUIT OF EXCELLENCE ON THE WORLD STAGE FER BANN MORISIEN DEVLOP ENN KILTIR KI VIZ NIVO EXSELANS LOR LASENN INTERNASIONAL Minister of Youth and Sports MESSAGE It is essential for every single Mauritian, and Mauritius as a Nation, to recognise the value of sport and physical activity in our daily lives, mental and physical wellbeing, productivity and future. We intend to use sport and physical activity through the delivery of this Policy as an opportunity to redefine our future and improve the lives of all our citizens. This Policy is both unique and timely: built upon a global review of best practices and deep local analysis we have created a ‘best in class’ policy against international benchmarks. It focuses on both physical activity and sport, describes tangible actions to address the health crisis our Nation is facing and outlines how we can create a more cohesive Mauritius through community sport. It also recognises our athletes’ essential role, our desire for success on the sporting stage and how these successes will collectively enhance our Nation’s international reputation. Sport and physical activity will also support our growing economy with new enterprises, jobs and a professional workforce. The twenty transformative actions that form the basis of the Policy provide a roadmap towards a healthier, wealthier, happier and enhanced Mauritius and define how our Nation will offer opportunities for everyone to participate, perform and benefit from sport and physical activity. -

Sport, Nationalism and Globalization: Relevance, Impact, Consequences

Hitotsubashi Journal of Arts and Sciences 49 (2008), pp.43-53. Ⓒ Hitotsubashi University SPORT, NATIONALISM AND GLOBALIZATION: RELEVANCE, IMPACT, CONSEQUENCES * ALAN BAIRNER Relevance International Sport At the most basiclevel of analysis, it is easy to see the extent to whichsport, arguably more than any other form of social activity in the modern world, facilitates flag waving and the playing of national anthems, both formally at moments such as medal ceremonies and informally through the activities of fans. Indeed there are many political nationalists who fear that by acting as such a visible medium for overt displays of national sentiment, sport can actually blunt the edge of serious political debate. No matter how one views the grotesque caricatures of national modes of behavior and dress that so often provide the colorful backdrop to major sporting events, one certainly cannot escape the fact that nationalism, in some form or another, and sport are closely linked. It is important to appreciate, however, that the precise nature of their relationship varies dramatically from one political setting to another and that, as a consequence, it is vital that we are alert to a range of different conceptual issues. For example, like the United Nations, sportʼs global governing bodies, such as the International OlympicCommittee or the Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA), consist almost exclusively of representatives not of nations but rather of sovereign nation states. It is also worth noting that pioneering figures in the organization of international sport, such as Baron Pierre de Coubertin who established the modern Olympics in 1896, commonly revealed a commitment to both internationalism and the interests of their own nation states. -

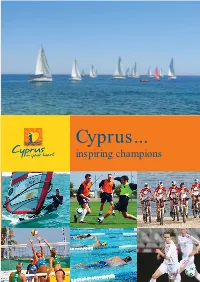

Visitcyprus.Com

Cyprus... inspiring champions “I found this training camp ideal. I must compliment the organisation and all involved for an excellent stay again. I highly recommend all professional teams to come to the island…” Gery Vink, Coach of Jong Ajax 1 Sports Tourism in Cyprus There are many reasons why athletes and sports lovers are drawn to the beautiful island of Cyprus… There’s the exceptional climate, the range of up-to-date sports facilities, the high-quality service industry, and the short travel times between city, sea and mountains. Cyprus offers a wide choice of sports facilities. From gyms Many international sports bodies have already recognized Cyprus to training grounds, from Olympic swimming pools to mountain as the ideal training destination. And it’s easy to see why National biking routes, there’s everything the modern sportsman or Olympic Committees from a number of countries have chosen woman could ask for. Cyprus as their pre-Olympic Games training destination. One of the world’s favourite holiday destinations, Cyprus also Medical care in Cyprus is of the highest standard, combining has an impressive choice of accommodation, from self-catering advanced equipment and facilities with the expertise of highly apartments to luxury hotels. When considering where to stay, it’s skilled practitioners. worth remembering that many hotels provide fully equipped The safe and friendly atmosphere also encourages athletes to fitness centres and health spas with qualified personnel - the bring families for an enjoyable break in the sun. Great restaurants, ideal way to train and relax. friendly cafes and great beaches make Cyprus the perfect place A gateway between Europe and the Middle East, Cyprus enjoys to unwind and relax. -

The Cyprus Sport Organisation and the European Union

TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................................................ 2 1. THE ESSA-SPORT PROJECT AND BACKGROUND TO THE NATIONAL REPORT ............................................ 4 2. NATIONAL KEY FACTS AND OVERALL DATA ON THE LABOUR MARKET ................................................... 8 3. THE NATIONAL SPORT AND PHYSICAL ACTIVITY SECTOR ...................................................................... 13 4. SPORT LABOUR MARKET STATISTICS ................................................................................................... 26 5. NATIONAL EDUCATION AND TRAINING SYSTEM .................................................................................. 36 6. NATIONAL SPORT EDUCATION AND TRAINING SYSTEM ....................................................................... 42 7. FINDINGS FROM THE EMPLOYER SURVEY............................................................................................ 48 8. REPORT ON NATIONAL CONSULTATIONS ............................................................................................ 85 9. NATIONAL CONCLUSIONS ................................................................................................................... 89 10. NATIONAL ACTION PLAN AND RECOMMENDATIONS ......................................................................... 92 BIBLIOGRAPHY ...................................................................................................................................... -

National Sport National Food: Sports in Global Games

S P A I N Capital: Madrid Official Language: Spanish National Animal: Bull National Sport Football National Food: Paella or Churros Sports in Global Games: Athletics and Swimming S P A I N Capital: Madrid Official Language: Spanish Head of State: His Majesty King Felipe VI Head of Government: Prime Minister HE Mr Perdro Sanchez Perez- Castejon Population: 46.3 million(2017) Land Area: 498,800 Sq km Currency: Euro Major Australian Exports: Coal, Fruit & nuts, electronic integrated circuits Sports in the Global Games: Athletics and Swimming S P A I N Located in south-western Europe, Spain borders the Mediterranean Sea, North Atlantic Ocean, Bay of Biscay and the Pyrenees Mountains. It covers an area of 498,800 sq km south-west of France. With a population of 46.4 million (2016), Spain’s official languages include Castilian (Spanish), Basque, Catalan and Galician. Ninety-four per cent of the population identifies as Roman Catholic. In the 2016 Census 119,952 Australian residents claimed Spanish descent, while 15,391 indicated they were born in Spain. The Spanish community in Australia comprises principally those who migrated to Australia in the 1960s under a government-to-government assisted migrant passage program, and their children, but also includes the descendants of nineteenth-century, primarily agricultural, immigrants. (Source: DFAT Website) G E R M A N Y Capital: Berlin Official Language: German National Animal: Black Eagle National Sport Football National Food: Bratwurst Sports in Global Games: Table Tennis G E R M A N Y Capital: -

The Social Dialogue in Professional Football at European and National Level ( Cyprus and Italy )

The Social Dialogue in professional football at European and National Level ( Cyprus and Italy ) By Dimitra Theodorou Supervisor: Professor Dr. Roger Blanpain Second reader: Dr. S.F.H.Jellinghaus Tilburg University LLM International and European Labour Law TILBURG 2013 1 Dedicated to: My own ‘hero’, my beloved mother Arsinoe Ioannou and to the memory of my wonderful grandmother Androulla Ctoridou-Ioannou. Acknowledgments: I wish to express my appreciation and gratitude to my honored Professor and supervisor of this Master Thesis Dr. Roger Blanpain and to my second reader Dr. S.F.H.Jellinghaus for all the support and help they provided me. This Master Thesis would not have been possible if I did not have their guidance and valuable advice. Furthermore, I would like to mention that it was an honor being supervised by Professor Dr. R. Blanpain and have his full support from the moment I introduced him my topic until the day I concluded this Master Thesis. Moreover, I would like to address special thanks to Mr. Spyros Neofitides, the president of PFA, and Mr. Stefano Sartori, responsible for the trade union issues and CBAs in the AIC, for their excellent cooperation and willingness to provide as much information as possible. In addition, I would like to thank Professor Dr. Michele Colucci, who introduced me to Sports Law and helped me with my research by not only providing relevant publications, but also by introducing me to Mr. Stefano Sartori. Last but not least, I want to thank all my friends for their support and patience they have shown all these months. -

Nationalism and Sporting Culture: a Media Analysis of Croatia's Participation in the 1998 World

Nationalism and Sporting Culture: A Media Analysis of Croatia’s Participation in the 1998 World Cup Andreja Milasincic, BPHED Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Applied Health Sciences (Health and Physical Education) Supervisor: Ian Ritchie, PhD Faculty of Applied Health Sciences, Brock University St. Catharines, Ontario L2S 3A1 Andreja Milasincic © November 2013 Abstract The past two centuries have witnessed the rise of nationalist movements and widespread nationalism. As these movements gained strength in Europe, sport played a role in their development. Media representations of sport recount events in a way that reinforces cultural values and this research investigates media representations of Croatian nationalism in the weeks surrounding the country’s third place victory in the 1998 FIFA World Cup. Sociological theories alongside more contemporary theories of sport and nation construction are considered. Croatian newspapers were analyzed for elements of national identity construction. The study concludes that the 1998 World Cup played an important role in Croatia’s on-going construction of nationhood and invention of nationalist traditions. This research further demonstrates sport’s ability to evoke strong emotions that are difficult to witness in other areas of social life and the direct role of sport in garnering nationalism. Keywords: nationalism, identities, newspapers, Croatia, soccer Acknowledgments The successful composition of this thesis required the support and direction of various individuals. First and foremost, a thank you to my supervisor, Dr. Ian Ritchie, for the countless hours spent encouraging, advising, and offering constructive criticisms throughout the research process. Your support and guidance have been not only appreciated but also vital to the completion of this thesis. -

Football Discipline As a Barometer of Racism in English Sport and Society, 2004-2007: Spatial Dimensions

Middle States Geographer, 2012, 44:27-35 FOOTBALL DISCIPLINE AS A BAROMETER OF RACISM IN ENGLISH SPORT AND SOCIETY, 2004-2007: SPATIAL DIMENSIONS M.T. Sullivan*1, J. Strauss*2 and D.S. Friedman*3 1Department of Geography Binghamton University Binghamton, New York 13902 2Dept. of Psychology Macalester College 1600 Grand Avenue St. Paul, MN 55105 3MacArthur High School Old Jerusalem Road Levittown, NY 11756 ABSTRACT: In 1990 Glamser demonstrated a significant difference in the disciplinary treatment of Black and White soccer players in England. The current study builds on this observation to examine the extent to which the Football Association’s antiracism programs have changed referee as well as fan behavior over the past several years. Analysis of data involving 421 players and over 10,500 matches – contested between 2003-04 and 2006-07 – indicates that a significant difference still exists in referees’ treatment of London-based Black footballers as compared with their White teammates at non-London matches (p=.004). At away matches in other London stadia, the difference was not significant (p=.200). Given the concentration of England’s Black population in the capital city, this suggests that it is fan reaction/overreaction to Black players’ fouls and dissent that unconsciously influences referee behavior. Keywords: racism, sport, home field advantage, referee discipline, match location INTRODUCTION The governing bodies of international football (FIFA) and English football (The FA or Football Association) have certainly tried to address racism in sport – a “microcosm of society.” In April of 2006, FIFA expelled five Spanish fans from a Zaragoza stadium and fined each 600 Euros for monkey chants directed towards Cameroonian striker Samuel Eto’o. -

Racism, Xenophobia and Structural Discrimination in Sports Country

® Racism, xenophobia and structural discrimination in sports Country report Germany Mario Peucker european forum for migration studies (efms) Bamberg, March 2009 Table of Content 1. Executive summary ...........................................................................4 2. Political and social context ...............................................................7 3. Racist incidents.................................................................................9 3.1. Racist incidents in organised men's amateur adult sport................9 3.2. Racist incidents in men's professional adult sport........................14 3.3. Racist incidents in organised women's amateur adult sport.........19 3.4. Racist incidents in women's professional adult sport...................19 3.5. Racist incidents in organised children's and youth sport .............20 4. Indirect (structural) racial/ethnic discrimination ............................21 4.1. Structural discrimination in all sports ..........................................21 4.2. Structural discrimination in the three focus sports .......................26 4.2.1. Organised men's amateur sport 26 4.2.2. Men's professional sport 29 4.2.3. Organised women's amateur sport 29 4.2.4. Women’s professional sport 30 4.2.5. Organised children's and youth sport 30 4.2.6. Media 31 5. Regulations and positive initiatives (good practice) ........................32 5.1. Regulations preventing racism, anti-Semitism and ethnic discrimination in sport ........................................................................32 -

Self-Determination and Indigenous Sport Policy in Canada

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Electronic Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers 1-1-2009 What is the spirit of our gathering? Self-determination and indigenous sport policy in Canada. Braden Paora Te Hiwi University of Windsor Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd Recommended Citation Te Hiwi, Braden Paora, "What is the spirit of our gathering? Self-determination and indigenous sport policy in Canada." (2009). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 7163. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd/7163 This online database contains the full-text of PhD dissertations and Masters’ theses of University of Windsor students from 1954 forward. These documents are made available for personal study and research purposes only, in accordance with the Canadian Copyright Act and the Creative Commons license—CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution, Non-Commercial, No Derivative Works). Under this license, works must always be attributed to the copyright holder (original author), cannot be used for any commercial purposes, and may not be altered. Any other use would require the permission of the copyright holder. Students may inquire about withdrawing their dissertation and/or thesis from this database. For additional inquiries, please contact the repository administrator via email ([email protected]) or by telephone at 519-253-3000ext. 3208. NOTE TO USERS This reproduction is the best copy available. UMI' What is the Spirit of our Gathering? Self-Determination and Indigenous Sport Policy in Canada. -

With God on Their Side

With God on their Side 'Sport' and 'religion' are cultural institutions with a global reach. Each is characterised by ritualised performance and by the ecstatic devotion of its followers, whether in the sports arena or the cathedral of worship. This fasci nating collection is the first to examine, in detail, the relationship between these two cultural institutions from an international, religiously pluralistic perspective. It illuminates the role of sport and religion in the social forma tion of collective groups and explores how sport might operate in the service of a religious community. The book offers a series of cutting-edge contemporary historical case studies, wide-ranging in their geographical coverage and in their social and religious contexts. It presents important new work on the following topics: • sport and Catholicism in Northern Ireland • Shinto and sumo in Japan • women, sport and American Jewish identity • religion, race and rugby in South Africa • sport and Islam in France and North Africa • sport and Christian fundamentalism in the US • Muhammad Ali and the Nation of Islam With God on their Side is vital reading for all students of the history, sociology and culture of sport. It also presents important new research material that will be of interest to religious studies students, historians and anthropologists. Tara Magdalinski is Senior Lecturer in Australian and Cultural Studies in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at the University of the Sunshine Coast, Queensland, Australia. Timothy J.L. Chandler is Associate Dean at the College of Fine and Professional Arts and Professor of Sport Studies in the School of Exercise, Leisure and Sport at Kent State University, USA. -

1 National Sports and National Landscapes: Real and Imagined Alan Bairner (Loughborough University, UK) Introduction: on Nations

National Sports and National Landscapes: real and imagined Alan Bairner (Loughborough University, UK) Introduction: On nations and nationalisms It is relatively standard practice in sociological and political studies of nations and nationalisms to differentiate between primordialist and modernist perspectives. Central to the former is the belief that the nation has its roots in one or more relatively objective criteria – language, ethnicity, geography, religion - which are almost certain to predate the emergence of the modern nation state and of nationalism as a modern political ideology. The modernist perspective, on the other hand, focuses on nations and nationalisms as modern inventions which emerge in response to new social and economic challenges. Somewhere between those two extreme positions is the view that whilst nations and nationalism are indeed modern, their existence and resilience rely heavily on the existence of certain historic criteria, both real and imagined, upon which nationalists themselves consistently draw. “Blood and soil” motifs are commonly thought of as the key ingredients of aggressive, xenophobic nationalism. For example, as Vejdovsky (Vejdovsky 10) notes, “Nazi propaganda would use the aesthetics of the pastoral to illustrate the necessity and the ethical justification of a garden like Lebensraum (vital space) where the germ of virtue of the Aryan race could be planted, and where it could grow to subdue and fill the earth”. Relatively seldom though is the actual physical character of the nation invoked by primordialists, compared with the frequent invocations of blood ties and 1 language. Nevertheless, Anthony D. Smith (Smith 56), more sympathetic than most academic commentators to the merits of primordialism, notes the territorial “homeland” component of nations and suggests that “the landscapes of the nation define and characterise the identity of its people”.