Studia Orientalia 112

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antiochus I Soter

Antiochus I Soter home : ancient Persia : ancient Greece : Seleucids : index : article by Jona Lendering Antiochus I Soter Antiochus I Soter ('the savior'): name of a Seleucid king, ruled from 281 to 261. Successor of: Seleucus I Nicator Relatives: Father: Seleucus I Nicator Coin of Antiochus I Soter Mother: Apame I, daughter of Spitamenes (Museum of Anatolian Wife: Stratonice I (his stepmother), daughter of Demetrius Civilizations, Ankara) Poliorcetes Children: Seleucus Laodice Apame II (married to Magas of Cyrene) Stratonice II (married to Demetrius II of Macedonia) Antiochus II Theos Main deeds: 301: Present during the Battle of Ipsus 294/293: marriage with his father's wife Stratonice I 292: made co-regent and satrap of Bactria (perhaps Seleucus was thinking of the ancient Achaemenid office of mathišta) Stay in Babylon (on several occasions?), where he showed an interest in the cults of Sin and Marduk, and in the rebuilding of the Esagila and Etemenanki September 281: death of Seleucus (more...); accession of Antiochus; Philetaerus of Pergamon buys back Seleucus' corpse 280-279: Brief war against Ptolemy II Philadelphus (First Syrian War, first part); Cappadocia becomes independent when its leader Ariarathes II and his ally Orontes III of Armenia defeat the Seleucid general Amyntas 279: Intervention in Greece: soldiers sent to Thermopylae to fight against the Galatians; they are defeated 275 Successful "Elephant Battle" against the Galatians; they enter his army as mercenaries; Antiochus is called Soter, 'victor' 274-271: Unsuccessful war against Ptolemy (First Syrian War, second part) 268: Stay in Babylonia; rebuilding of the Ezida in Borsippa 266: Execution of his son Seleucus 263: Eumenes I of Pergamon, successor of Philetaerus, declares himself independent 262: Antiochus defeated by Eumenes Page 1 Antiochus I Soter 262: Antiochus defeated by Eumenes Dies 2 June 261 Succeeded by: Antiochus II Theos Sources: During Antiochus' years as crown prince, he played a large role in Babylonian policy. -

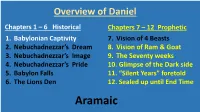

Aramaic Chapter 22 Chapter 7 Chapter 8

Overview of Daniel Chapters 1 – 6 Historical Chapters 7 – 12 Prophetic 1. Babylonian Captivity 7. Vision of 4 Beasts 2. Nebuchadnezzar’s Dream 8. Vision of Ram & Goat 3. Nebuchadnezzar’s Image 9. The Seventy weeks 4. Nebuchadnezzar’s Pride 10. Glimpse of the Dark side 5. Babylon Falls 11. “Silent Years” foretold 6. The Lions Den 12. Sealed up until End Time Aramaic Chapter 22 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Babylon Medo- Persia Greece Rome Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Persians Medes Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 8 Greek Empire Alexander The Great Lysimachus Cassander Ptolemy Seleucus Greek Empire Chapter 8 Alexander The Great King of the South King of the North 1. Ptolemy I Soter 1. Seleucus I Nicator 2. Antiochus I Soter 2. Ptolemy II Philadelphus 3. Antiochus II Theos 3. Ptolemy III Euergetes 4. Seleucus II Callinicus 5. Seleucus III Ceraunus 4. Ptolemy IV Philopator 6. Antiochus III Great 5. Ptolemy V Epiphanes 7. Seleucus IV Philopator 6. Ptolemy VI Philometor 8. Antiochus IV Epiphanes The account in 1 Maccabees continues: “Mothers who had allowed their babies to be circumcised were put to death in accordance with the king’s decree. Their babies were hung around their necks, and their families and those who had circumcised them were put to death” (1:60, TEV). ROME 10 11 8 D.T. BEAST 10 HORNS LITTLE HORN ANTI-CHRIST 3 FELL EYES & MOUTH LARGER THAN ASSOCIATES How Long? 2300 evenings & mornings = 167 BC 164 BC Antiochus Antiochus dies sacrificed a pig on the altar Start of Temple Maccabean Rededicated / Revolt cleansed He who has an ear, let him hear what the Spirit says to the churches.‘ Rev 2:7 Rev 2:11 Rev 2:17 Rev 2:29 Rev 3:6 Rev 3:13 Rev 3:22 To Gorsley in 2011 The Lord is sharpening the focus of the church and wants you to respond: with prayer and fasting and repentance and have ears to hear what the Spirit is saying and hearts and wills to respond to His leading and directing. -

A Chronological Particular Timeline of Near East and Europe History

Introduction This compilation was begun merely to be a synthesized, occasional source for other writings, primarily for familiarization with European world development. Gradually, however, it was forced to come to grips with the elephantine amount of historical detail in certain classical sources. Recording the numbers of reported war deaths in previous history (many thousands, here and there!) initially was done with little contemplation but eventually, with the near‐exponential number of Humankind battles (not just major ones; inter‐tribal, dynastic, and inter‐regional), mind was caused to pause and ask itself, “Why?” Awed by the numbers killed in battles over recorded time, one falls subject to believing the very occupation in war was a naturally occurring ancient inclination, no longer possessed by ‘enlightened’ Humankind. In our synthesized histories, however, details are confined to generals, geography, battle strategies and formations, victories and defeats, with precious little revealed of the highly complicated and combined subjective forces that generate and fuel war. Two territories of human existence are involved: material and psychological. Material includes land, resources, and freedom to maintain a life to which one feels entitled. It fuels war by emotions arising from either deprivation or conditioned expectations. Psychological embraces Egalitarian and Egoistical arenas. Egalitarian is fueled by emotions arising from either a need to improve conditions or defend what it has. To that category also belongs the individual for whom revenge becomes an end in itself. Egoistical is fueled by emotions arising from material possessiveness and self‐aggrandizations. To that category also belongs the individual for whom worldly power is an end in itself. -

Antiochus IV Rome

Chapter 22 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9 Chapter 11 & 12 Babylon Medo- 445BC 4 Persian Kings Persia Alex the Great Greece N&S Kings Antiochus IV Rome Gap of Time Time of the Gentiles 1wk 3 ½ years Opposing king. Greek Empire Chapter 8 Alexander The Great King of the South King of the North 1. Ptolemy I Soter 1. Seleucus I Nicator 2. Antiochus I Soter 2. Ptolemy II Philadelphus 3. Antiochus II Theos 3. Ptolemy III Euergetes 4. Seleucus II Callinicus 5. Seleucus III Ceraunus 4. Ptolemy IV Philopator 6. Antiochus III Great 5. Ptolemy V Epiphanes 7. Seleucus IV Philopator 6. Ptolemy VI Philometor 8. Antiochus IV Epiphanes Daniel 9:27 The 70th Week 1 Week = 7 years 3 ½ years 3 ½ years Apostasy Make a covenant Stop to Temple sacrifice with the many Stop to grain offering Abomination of Desolation Crush the elect (Jews) Jacob’s Distress Jacob’s Trouble Tribulation Daniel 11:35 Some of those who have insight will fall, in order to refine, purge and make them pure until the end time; because it is still to come at the appointed time 1 John 3:2-3 2 Beloved, now we are children of God, and it has not appeared as yet what we will be. We know that when He appears, we will be like Him, because we will see Him just as He is. 3 And everyone who has his hope fixed on Him purifies himself, just as He is pure. Zechariah 13:7-9 8 “It will come about in all the land,” Declares the LORD, “That two parts in it will be cut off and perish; But the third will be left in it. -

The First Century of Seleucid Rule

Seleucid Study Day III: War within the Family: The First Century of Seleucid Rule. Bordeaux: Seleucid Study Group, Classical Press of Wales, Université de Bordeaux III, 05.09.2012-07.09.2012. Reviewed by Altay Coskun Published on H-Soz-u-Kult (October, 2012) As hosts of the VIIth Celtic Conference of Clas‐ convenor KYLE ERICKSON (Lampeter) identified sics Cf. the program of VIIth CCC: various desiderata: frst the necessity to more sys‐ http://www.ucd.ie/t4cm/Vi‐ tematically integrate into the picture the satrapies ieme%20Celtic%20Conference%20in%20Classics%20July%202012.pdfeast of the Euphrates as well as to analyse the (11.10.2012). , Anton Powell (Classical Press of continuity and ruptures in the transition from the Wales, Swansea) and Jean Yvonneau (University Achaemenid to the Seleucid Empires; secondly, to of Bordeaux III) invited the Seleucid Study Group focus more strongly on the periods intervening to organize a panel on the early Seleucid Kingdom between the rules of Seleucus I (320/311-281) and (3rd century BC). After previous gatherings at Ex‐ Antiochus III (223-187); and thirdly to reconsider eter and Waterloo in 2011, this meeting was the the roles of Seleucid royal women. third in a (counted) series dedicated to a collabo‐ Mitchell’s paper highlighted caution in using rative and interdisciplinary research agenda on a simple model of subjugation by suggesting a one of the most under-explored world empires. In new approach to Macedonian colonies in Asia Mi‐ fact, the roots of this joint effort goes back to pre‐ nor. Most of them had not been initiated and or‐ vious conferences in Exeter (2008) and Waterloo ganized by Hellenistic kings but were owed to (2010), as STEPHEN MITCHELL (Exeter) explained Greek or Macedonian private initiatives mainly in his welcome address. -

Handout: Daniel Lesson 7 Daniel 11:2-45 Covers the Period from the Persian Age to Seleucid Ruler Antiochus IV in Three Parts: 1

Handout: Daniel Lesson 7 Daniel 11:2-45 covers the period from the Persian Age to Seleucid ruler Antiochus IV in three parts: 1. The Persian kings from Cambyses to Xerxes I: 529-465 BC (11:2) 2. Alexander the Great and the division of his empire: 336-323 BC (11:3-4). 3. Battles of the Greek Seleucids, the kings of the north and the Greek Ptolemies, the kings of the south (11:5-45). Part three concerning the history of the Greek Seleucids and Greek Ptolemies divides into six sections (11:5-45): 1. The reigns Ptolemy I Soter, 323-285 BC, and Seleucus I Nicator 312/11-280 BC (11:5) 2. The intrigues of Ptolemy II Philadelphus 285-246 BC and Antiochus II Theos 261-246 BC (11:6). 3. The revenge of Ptolemy III Evergetes 246-221 for the deaths of his sister Berenice and her baby by making war against the kingdom of Seleucus II Collinicus 246-226 BC (11:7-9). 4. The reign of Antiochus IV the Great 223-187 BC (11:10-19). 5. The reign of Seleucus IV Philopator 187-175 BC (11:20). 6. The cruel reign of Antiochus IV Epiphanes 175-164 BC, his persecution of the Jews, and his destruction (11:21-45). 2 Three more kings are going to rise in Persia; a fourth will come and be richer than all the others, and when, thanks to his wealth, he has grown powerful, he will make war on all the kingdoms of Greece. The four kings of Persia who came after Cyrus: 1. -

Daniel 11:1-19 Commentary

Daniel 11:1-19 Commentary Click chart to enlarge PREVIOUS Charts from recommended resource Jensen's Survey of the OT - used by permission NEXT Daniel 11:1 "IN THE FIRST YEAR OF DARIUS THE MEDE, I AROSE TO BE AN ENCOURAGEMENT AND A PROTECTION FOR HIM. First year: Da 5:31 9:1 Be an encouragement: Da 10:18 Ac 14:22 Daniel 11 Resources - Multiple Sermons and Commentaries Daniel 11:1 - Fits Better as Last Verse of Daniel 10 Daniel 11:2 - Persia Prophecy Daniel 11:3-4 - Alexander the Great/Greek Prophecy Daniel 11:5-20 - Seleucid and Ptolemy Prophecies Daniel 11:21-35 - Despicable Person Prophecy Daniel 11:36-45 - King Does As He Pleases Prophecy First year of Darius - 538BC I arose - This is still the supernatural interpreter of Daniel 10, presumably an angel. This verse would best be included at the end of Daniel 10 not the beginning of Daniel 11. Obviously the "chapter breaks" are not inspired but added by men. Encouragement (02388) (chazaq) means to make firm or strong, to strengthen, to give strength, to encourage (frome n = in + coeur = the heart) (to fill with courage or strength of purpose). Protection (04581) (ma'oz) signifies a stronghold or fortress, a protected place, a place of safety. Ma'oz - Seven of 35 OT uses are in Daniel 11 - Jdg 6:26; 2Sa 22:33; Neh 8:10; Ps 27:1; 28:8; 31:2, 4; 37:39; 43:2; 52:7; 60:7; 108:8; Pr 10:29; Isa 17:9, 10; 23:4, 11, 14; 25:4; 27:5; 30:2, 3; Jer 16:19; Ezek 24:25; 30:15; Da 11:1, 7, 10, 19, 31, 38, 39; Joel 3:16; Nah 1:7; 3:11 To be an encouragement and protection for him - The benevolent angel's role in the context of angelic conflict over the Persian empire reflects the supernatural protection God provided through His angel for King Darius the Mede, who reaffirmed the decree by Cyrus which permitted Israel to rebuild their Holy Temple in Jerusalem including the return of the Holy utensils used in Temple worship (see Ezra 6:1, 2, 3, 4, 5). -

Queen Regency in the Seleucid Empire

Interregnum: Queen Regency in the Seleucid Empire by Stacy Reda A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in Ancient Mediterranean Cultures Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2014 © Stacy Reda 2014 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract An examination of the ancient sources indicates that there were possibly seven Queens Regent throughout the course of the Seleucid Dynasty: Apama, Laodice I, Berenice Syra, Laodice III, Laodice IV, Cleopatra I Thea, and Cleopatra II Selene. This thesis examines the institution of Queen Regency in the Seleucid Dynasty, the power and duties held by the Queen Regent, and the relationship between the Queen and her son—the royal heir. This thesis concludes that Queen Regency was not a set office and that there were multiple reasons and functions that could define a queen as a regent. iii Acknowledgements I give my utmost thanks and appreciation to the University of Waterloo’s Department of Classical Studies. The support that I have received from all members of the faculty during my studies has made a great impact on my life for which I will always be grateful. Special thanks to my advisor, Dr. Sheila Ager, for mentoring me through this process, and Dr. Maria Liston (Anthropology) for her support and guidance. -

Sogdiana During the Hellenistic Period by Gurtej Jassar B.Sc, Th

Hellas Eschate The Interactions of Greek and non-Greek Populations in Bactria- Sogdiana during the Hellenistic Period by Gurtej Jassar B.Sc, The University of British Columbia, 1992 B.A.(Hon.), The University of British Columbia, 1995 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of Classical, Near Eastern, and Religious Studies) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April 1997 ©Gurtej Jassar, 1997 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of OA,S5J The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada DE-6 (2/88) II ABSTRACT This study deals with the syncretism between Greek and non-Greek peoples as evidenced by their architectural, artistic, literary and epigraphic remains. The sites under investigation were in the eastern part of the Greek world, particularly Ai Khanoum, Takht-i-Sangin, Dilberdjin, and Kandahar. The reason behind syncretism was discussed in the introduction, which included the persistence of the ancient traditions in Egypt, Mesopotamia, and Bactria even after being conquered by the Greeks. -

Studies in the Archaeology of Hellenistic Pontus: the Settlements, Monuments, and Coinage of Mithradates Vi and His Predecessors

STUDIES IN THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF HELLENISTIC PONTUS: THE SETTLEMENTS, MONUMENTS, AND COINAGE OF MITHRADATES VI AND HIS PREDECESSORS A dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D.) In the Department of Classics of the College of Arts and Sciences 2001 by D. Burcu Arıkan Erciyas B.A. Bilkent University, 1994 M.A. University of Cincinnati, 1997 Committee Chair: Prof. Brian Rose ABSTRACT This dissertation is the first comprehensive study of the central Black Sea region in Turkey (ancient Pontus) during the Hellenistic period. It examines the environmental, archaeological, literary, and numismatic data in individual chapters. The focus of this examination is the central area of Pontus, with the goal of clarifying the Hellenistic kingdom's relationship to other parts of Asia Minor and to the east. I have concentrated on the reign of Mithradates VI (120-63 B.C.), but the archaeological and literary evidence for his royal predecessors, beginning in the third century B.C., has also been included. Pontic settlement patterns from the Chalcolithic through the Roman period have also been investigated in order to place Hellenistic occupation here in the broadest possible diachronic perspective. The examination of the coinage, in particular, has revealed a significant amount about royal propaganda during the reign of Mithradates, especially his claims to both eastern and western ancestry. One chapter deals with a newly discovered tomb at Amisos that was indicative of the aristocratic attitudes toward death. The tomb finds indicate a high level of commercial activity in the region as early as the late fourth/early third century B.C., as well as the significant role of Amisos in connecting the interior with the coast. -

La Basilissa En Els Regnes Hel·Lenístics Selèucides

La basilissa en els regnes hel·lenístics selèucides Ester Gomà Juncosa Tutor: Victor Revilla Calvo Curs 2017-2018 Treball Final de Grau Grau d'Història Facultat de Geografia i Història Índex INTRODUCCIÓ ............................................................................................................................................... 2 I. LA IDEOLOGIA DE LA MONARQUIA HEL·LENÍSTICA I EL PAPER PÚBLIC DE LA REINA. 4 1. LA MONARQUIA HEL·LENÍSTICA ................................................................................................................. 4 1.1. La naturalesa militar de la monarquia hel·lenística .......................................................................... 4 1.2. Les influències macedòniques i aquemènides .................................................................................... 5 1.3. La ideologia de la monarquia hel·lenística ........................................................................................ 7 2. L’EVOLUCIÓ DEL PAPER PÚBLIC DE LA REINA ............................................................................................. 9 1. Les dones argèades com a primer model .............................................................................................. 9 2. D’esposa a basilissa: legitimació del poder reial ............................................................................... 11 3. De la poligàmia a la monogàmia: Evolució de la imatge pública de la reina.................................... 14 4. La imatge de la reina: Els retrats perduts ......................................................................................... -

The Discovery of India by the Greeks

The discovery of India by the Greeks Autor(en): Jong, J.W. de Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: Asiatische Studien : Zeitschrift der Schweizerischen Asiengesellschaft = Études asiatiques : revue de la Société Suisse-Asie Band (Jahr): 27 (1973) Heft 2 PDF erstellt am: 10.10.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-146366 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch THE DISCOVERY OF INDIA BY THE GREEKS* J.W. DE JONG One of the first records of India is to be found in the inscriptions of the rulers of the Achaemenid empire in Persia. Darius who reigned from 522 to 48 5 enumerates among the countries which belonged to his empire Gadära and Hidu.