Conservation Status and Protection of Migratory Species in Germany

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Godesberg Programme and Its Aftermath

Karim Fertikh The Godesberg Programme and its Aftermath A Socio-histoire of an Ideological Transformation in European Social De- mocracies Abstract: The Godesberg programme (1959) is considered a major shift in European social democratic ideology. This article explores its genesis and of- fers a history of both the written text and its subsequent uses. It does so by shedding light on the organizational constraints and the personal strategies of the players involved in the production of the text in the Social Democra- tic Party of Germany. The article considers the partisan milieu and its trans- formations after 1945 and in the aftermaths of 1968 as an important factor accounting for the making of the political myth of Bad Godesberg. To do so, it explores the historicity of the interpretations of the programme from the 1950s to the present day, and highlights the moments at which the meaning of Godesberg as a major shift in socialist history has become consolidated in Europe, focusing on the French Socialist Party. Keywords: Social Democracy, Godesberg Programme, socio-histoire, scienti- fication of politics, history of ideas In a recent TV show, “Baron noir,” the main character launches a rant about the “f***g Bad Godesberg” advocated by the Socialist Party candidate. That the 1950s programme should be mentioned before a primetime audience bears witness to the widespread dissemination of the phrase in French political culture. “Faire son Bad Godesberg” [literally, “doing one’s Bad Godesberg”] has become an idiomatic French phrase. It refers to a fundamental alteration in the core doctrinal values of a politi- cal party (especially social-democratic and socialist ones). -

Central Europe

Central Europe West Germany FOREIGN POLICY wTHEN CHANCELLOR Ludwig Erhard's coalition government sud- denly collapsed in October 1966, none of the Federal Republic's major for- eign policy goals, such as the reunification of Germany and the improvement of relations with its Eastern neighbors, with France, NATO, the Arab coun- tries, and with the new African nations had as yet been achieved. Relations with the United States What actually brought the political and economic crisis into the open and hastened Erhard's downfall was that he returned empty-handed from his Sep- tember visit to President Lyndon B. Johnson. Erhard appealed to Johnson for an extension of the date when payment of $3 billion was due for military equipment which West Germany had bought from the United States to bal- ance dollar expenses for keeping American troops in West Germany. (By the end of 1966, Germany paid DM2.9 billion of the total DM5.4 billion, provided in the agreements between the United States government and the Germans late in 1965. The remaining DM2.5 billion were to be paid in 1967.) During these talks Erhard also expressed his government's wish that American troops in West Germany remain at their present strength. Al- though Erhard's reception in Washington and Texas was friendly, he gained no major concessions. Late in October the United States and the United Kingdom began talks with the Federal Republic on major economic and military problems. Relations with France When Erhard visited France in February, President Charles de Gaulle gave reassurances that France would not recognize the East German regime, that he would advocate the cause of Germany in Moscow, and that he would 349 350 / AMERICAN JEWISH YEAR BOOK, 1967 approve intensified political and cultural cooperation between the six Com- mon Market powers—France, Germany, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg. -

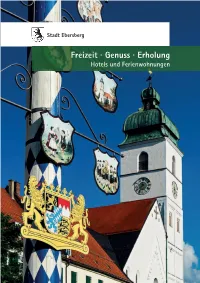

Freizeit · Genuss · Erholung

Stadt Ebersberg Freizeit · Genuss · Erholung Hotels und Ferienwohnungen Inhaltsverzeichnis Seite 4 – 5 Zwischen München und den Alpen Seite 6 – 7 Historisches Erbe Seite 8 – 9 Sehenswürdigkeiten Seite 10 – 11 Ebersberger Stadtführungen Seite 12 – 13 Naturschönheiten Seite 14 – 15 Aktiv in der Natur Seite 16 – 17 Kulturfeuer Seite 18 – 19 Veranstaltungen – Die Highlights Seite 20 – 21 Kurze Wege zu Ihrer Tagung Seite 22 – 23 Einkaufen & Gastronomie Seite 24 – 25 Anreise / Überblick Seite 26 – 27 Hotels und Ferienwohnungen Seite 28 Business Class Hotel / Hotel Hölzer Bräu Seite 29 Hotel-Gasthof Huber / Hotel „seeluna“ Seite 30 – 32 Appartements / Ferien- / Gästehäuser Seite 34 – 35 Ebersberger Stadtplan Seite 36 Hörpfade Ebersberg Seite 38 Museum Wald und Umwelt Seite 39 Erläuterung der Piktogramme Liebe Gäste, auf den nachfolgenden Seiten möchten wir Ihnen möglichst kompakt Informa- tionen über unsere Sehenswürdigkeiten, Freizeitmöglichkeiten und Gastgeber auf- zeigen und Ihnen somit Lust auf einen Besuch unserer schönen Stadt machen. Ebersberg, rund 30 km östlich der Landes- hauptstadt München gelegen, ist gut mit PKW, Bahn und Flugzeug zu erreichen. Dank der verkehrsgünstigen Lage sind wir idealer Ausgangspunkt für Ausflüge nach München und ins oberbayerische Umland. Auch zur nahe gelegenen Messe München und in die Berge gelangt man von hier aus schnell. Die Geschichte unserer Stadt ist eng mit dem Kloster Ebersberg und der Wallfahrt ver- bunden und unsere Innenstadt mit vielen gut erhaltenen historischen Gebäuden ist am besten im Rahmen einer Stadtführung erlebbar. Einheimische und Besucher genießen gerne die echte bayerische Tradition und Veranstaltungen, wie das jährlich stattfin- dende Volksfest. Und die reizvolle hügelige Voralpenlandschaft sowie der angrenzende Ebersberger Forst, eines der größten zusammenhängenden Waldgebiete Deutschlands, bieten hervorragende Voraussetzungen für abwechslungsreiche Wander- und Rad- touren. -

An Integrated Marine Data Collection for the German Bight

Discussions https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-2021-45 Earth System Preprint. Discussion started: 16 February 2021 Science c Author(s) 2021. CC BY 4.0 License. Open Access Open Data An Integrated Marine Data Collection for the German Bight – Part II: Tides, Salinity and Waves (1996 – 2015 CE) Robert Hagen1, Andreas Plüß1, Romina Ihde1, Janina Freund1, Norman Dreier2, Edgar Nehlsen2, Nico Schrage³, Peter Fröhle2, Frank Kösters1 5 1Federal Waterways Engineering and Research Institute, Hamburg, 22559, Germany 2Hamburg University of Technology, Hamburg, 21073, Germany ³Bjoernsen Consulting Engineers, Koblenz, 56070, Germany Correspondence to Robert Hagen ([email protected], ORCID: 0000-0002-8446-2004) 10 Abstract The German Bight within the central North Sea is of vital importance to many industrial nations in the European Union (EU), which have obligated themselves to ensure the development of green energy facilities and technology, while improving natural habitats and still being economically competitive. These ambitious goals require a tremendous amount of careful planning and considerations, which depends heavily on data availability. For this reason, we established in close cooperation with 15 stakeholders an open-access integrated, marine data collection from 1996 to 2015 for bathymetry, surface sediments, tidal dynamics, salinity, and waves in the German Bight for science, economy, and governmental interest. This second part of a two-part publication presents data products from numerical hindcast simulations for sea surface elevation, current velocity, bottom shear stress, salinity, wave parameters and wave spectra. As an important improvement to existing data collections our model represents the variability of the bathymetry by using annually updated model topographies. -

Regionales Naturschutzkonzept Für Den Forstbetrieb Wasserburg Am Inn

Regionales Naturschutzkonzept für den Forstbetrieb Wasserburg am Inn Stand: Mai 2013 Naturschutzkonzept Forstbetrieb Wasserburg 1 Verantwortlich für die Erstellung Bayerische Staatsforsten Bayerische Staatsforsten Zentrale Forstbetrieb Wasserburg Bereich Waldbau, Naturschutz, Jagd und Fischerei Salzburger Straße 14 Naturschutzspezialist Klaus Huschik 83512 Wasserburg Hindenburgstraße 30 Tel.: 08071 - 9236- 0 83646 Bad Tölz [email protected] Hinweis Alle Inhalte dieses Naturschutzkonzeptes, insbesondere Texte, Tabellen und Abbildungen sind urheberrechtlich geschützt (Copyright). Das Urheberrecht liegt, soweit nicht ausdrücklich anders gekennzeichnet, bei den Bayeri- schen Staatsforsten. Nachdruck, Vervielfältigung, Veröffentlichung und jede andere Nutzung bedürfen der vorherigen Zustimmung des Urhebers. Wer das Urheberrecht verletzt, unterliegt der zivilrechtlichen Haftung gem. §§ 97 ff. Urheberrechtsgesetz und kann sich gem. §§ 106 ff. Urheberrechtsgesetz strafbar machen. Naturschutzkonzept Forstbetrieb Wasserburg 2 Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Zusammenfassung ............................................................................................... 5 2 Allgemeines zum Forstbetrieb Wasserburg ....................................................... 7 2.1 Kurzcharakteristik für den Naturraum .................................................................................... 8 2.2 Ziele der Waldbewirtschaftung ............................................................................................... 9 3 Naturschutzfachlicher Teil -

Anlage 2: Wildbäche

Anlage 2 Wildbäche lfd. Kenn-Nr. Einzugsgebiet Anfangspunkt Endpunkt Bemerkungen Nr. 1 Regierungsbezirk Oberbayern (41) 2 Wildbäche im Amtsbereich des WWA München (412) 3 412001 Klosterschluchtgraben Kreuzung mit der Bundesstraße 11 in Unteres Ende des Schluchtlaufs ca. 200 m Ebenhausen, Gde. Schäftlarn, Lkr. westlich der Staatsstraße 207, Gde. München Schäftlarn, Lkr. München 4 Wildbäche im Amtsbereich des WWA Rosenheim (413) 5 413021 Achen (Thalkirchner Ache) Ursprung beim Stöttener Filz, Gde. Mündung in den Simssee, Markt Bad Frasdorf, Lkr. Rosenheim Endorf, Lkr. Rosenheim 6 413093 Almgraben Ursprung zwischen kleinem Tegernseer Mündung in den Tegernsee, Stadt Berg und Riederstein, Stadt Tegernsee, Tegernsee, Lkr. Miesbach Lkr. Miesbach 7 413087 Alpbach (MB) Ursprung zwischen Ostiner Berg, Mündung in den Tegernsee, Stadt Baumgartenschneid und kleinem Tegernsee, Lkr. Miesbach Tegernseer Berg, Stadt Tegernsee, Lkr. Miesbach 8 413080 Altdorfer Mühlbach Straßendurchlass unterhalb Gern, Gde. Mündung in den Nasenbach, Markt Gars Soyen, Lkr. Rosenheim a.Inn, Lkr. Mühldorf a.Inn 9 413048 Ameranger Dorfbach Ursprünge nördlich und südwestlich von Brücke Gemeindestraße Amerang - Taiding, Gde. Amerang, Lkr. Rosenheim Kammer, Gde. Amerang, Lkr. Rosenheim 10 413024 Angerbach (RO) Ursprung östlich von Haring, Gde. Mündung in den Simssee, Gde. Riedering, Riedering, Lkr. Rosenheim Lkr. Rosenheim 11 413025 Antworter Berg: Gräben am Ursprung am Antworter Berg, Markt Bad Mündung in die Antworter Ache bzw. Nordwesthang Endorf, Lkr. Rosenheim Einlauf in die Rohrleitung südlich von Antwort, Markt Bad Endorf, Lkr. Rosenheim 12 413045 Aubach (RO) Ursprung auf der Niklasreuther Höhe, Gde. Ehemalige Bahnbrücke unterhalb von Au, Ausgenommen Zufluss aus Irschenberg, Lkr. Miesbach Gde. Bad Feilnbach, Lkr. Rosenheim Brettschleipfen 13 413006 Auerbach Ursprung östlich des Tagweidkopfes, Gde. -

BROWN COLT Foaled 8Th September 2015

BROWN COLT Foaled 8th September 2015 Sire Dynaformer Roberto Hail to Reason AMERICAIN (USA) Andover Way His Majesty 2005 America Arazi Blushing Groom Green Rosy Green Dancer Dam Hussonet Mr. Prospector Raise a Native LAVENHAM Sacahuista Raja Baba 2010 Lady Succeed Brian's Time Roberto Hydro Calido Nureyev AMERICAIN (USA) (Bay or Brown 2005-Stud U.S.A. 2013, Aust. 2013). Head of the 2011 World Thoroughbred Rankings (Ext.). 11 wins-1 at 2-from 1400m to 3200m, VRC Melbourne Cup, Gr.1, MRC Zipping Classic, Gr.2. Half-brother to SP Amarak, SP Spycrawler and SP Last Born. Sire of Folk Magic, Lizzie's Way and of the placegetters American Deluxe, Bella Bella, Derval, Domestic Vintage, etc. His oldest Aust.-bred progeny are 2YOs and inc the placegetters Aspen Angel, Geegee Blackprince, etc. 1st dam LAVENHAM, by Hussonet. 2 wins at 1100m, 1150m. Half-sister to Supido. This is her first foal. 2nd dam LADY SUCCEED, by Brian's Time. 2 wins at 1700m, 1800m in Japan. Half-sister to ESPERERO, SHINKO CALIDO, Heraklia (dam of FIFTY ONER). Dam of 6 named foals, 4 to race, all winners, inc:- Supido (Sebring). 6 wins to 1200m, A$380,400, to 2015-16, VRC Dalray H., AB/ATA Celebrates Women Trainers H., Phillip Schuler H., Michael Stewart H., MRC The Cove Hotel P., MVRC PKF Tour of Victoria Sprint H., 2d MRC Pancare Foundation P., 3d SAJC Goodwood S., Gr.1, ATC Challenge S., Gr.2. Kung Hei Fat Choy. 9 wins from 7f to 1m, 3d Doncaster William Hill Download the App H. -

Gemeinsame Zeitung „Gutetiden“ Der Ostfriesischen Insel Erschienen Ostfriesische Inseln Gmbh Goethestr

Auslagehinweis Gemeinsame Zeitung „gutetiden“ der Ostfriesischen Insel erschienen Ostfriesische Inseln GmbH Goethestr. 1 26757 Borkum T. 04922 933 120 M. 0151 649 299 53 Geschäftsführer: Göran Sell www.ostfriesische-inseln.de gutetiden Ausgabe 01 - Das Beste in der Nordsee. In unserer ersten Ausgabe von "gutetiden" erfahren Sie mehr zur Gründung der Ostfriesische Inseln GmbH, zum kostbaren Vermächtnis - dem UNESCO-Weltnaturerbe Wattenmeer, sehen die Inselwelt von oben und erfahren Spannendes über das Leben der Insulaner. gutetiden ist auf den Inseln in den Tourist Informationen erhältlich oder kann ganz bequem über diesen Link geblättert https://issuu.com/ostfriesische-inseln/docs/zeitung- ofi_ausgabe_01 werden. Viel Freude beim Lesen. www.ostfriesische-inseln.de Auf Wangerooge finden Interessierte die „gutetiden“ im ServiceCenter der Kurverwaltung sowie in der Tourist Information in der Zedeliusstraße und im Meerwasser-Erlebnisbad und Gesundheitszentrum Oase. Über die Ostfriesische Inseln GmbH: Die Ostfriesische Inseln GmbH wurde im Dezember 2017 als Dachorganisation gegründet. Ihr Anspruch ist es, die Stärken der Ostfriesischen Inseln nach außen zu tragen und sie als international führende Urlaubsregion zu etablieren. Schon jetzt gehören die Ostfriesischen Inseln zu den Top-Destinationen in Deutschland. Durch den Tourismus erwirtschaften sie einen Bruttoumsatz von rund 1 Milliarde Euro im Jahr. Gesellschafter der Ostfriesische Inseln GmbH sind die Tourismusorganisationen der Inseln Borkum, Juist, Norderney, Langeoog, Spiekeroog und Wangerooge – außerdem die Reedereien AG EMS, AG Norden- Frisia, Baltrum-Linie GmbH & Co. KG, Schiffahrt Langeoog, Schifffahrt Spiekeroog und in Kürze auch Schifffahrt Wangerooge. Der Geschäftsführer der Ostfriesische Inseln GmbH ist Göran Sell, der gleichzeitig auch Geschäftsführer der Nordseeheilbad Borkum GmbH ist. Den Vorsitz der Gesellschafterversammlung hat Wilhelm Loth, Geschäftsführer der Staatsbad Norderney GmbH. -

The Visitation of Alois Ersin, S.J., to the Province of Lower Germany in 1931

Chapter 10 The Visitation of Alois Ersin, S.J., to the Province of Lower Germany in 1931 Klaus Schatz, S.J. Translated by Geoffrey Gay 1 Situation and Problems of the Province Around the year 1930, the Lower German province of the Society of Jesus was expanding but not without problems and internal tensions.1 The anti-Jesuit laws passed in 1872 during the Kulturkampf had been abrogated in 1917.2 The Weimar Constitution of 1919 had dismantled the final barriers that still existed between the constituent elements of Germany and granted religious freedom. The German province numbered 1,257 members at the beginning of 1921, when the province was divided into two: the Lower German (Germania Inferior) and the Upper German (Germania Superior), known informally as the northern and southern provinces. The southern or Upper German province, with Munich as its seat, comprised Jesuit communities in the states of Bavaria, Württemberg, Baden, and Saxony. These consisted of Munich (three residences), Aschaffen- burg, Nuremberg, Straubing, Rottmannshöhe (a retreat house), Stuttgart, and Dresden. The northern or Lower German province, with Cologne as its seat, was spread over the whole of northern Germany and included the territory of Prussia and the smaller states of northern Germany (of which only Hamburg had a Jesuit residence). At the time of the division, the new province contained fifteen residences: Münster in Westphalia, Dortmund, Essen, Duisburg, Düs- seldorf, Aachen, Cologne, Bonn, Bad Godesberg (Aloisiuskolleg), Waldesruh, 1 See Klaus Schatz, S.J., Geschichte der deutschen Jesuiten 1814–1983, 5 vols. (Münster/W.: Aschendorff, 2013) for greater detail. -

Disclosure Guide

WEEKS® 2021 - 2022 DISCLOSURE GUIDE This publication contains information that indicates resorts participating in, and explains the terms, conditions, and the use of, the RCI Weeks Exchange Program operated by RCI, LLC. You are urged to read it carefully. 0490-2021 RCI, TRC 2021-2022 Annual Disclosure Guide Covers.indd 5 5/20/21 10:34 AM DISCLOSURE GUIDE TO THE RCI WEEKS Fiona G. Downing EXCHANGE PROGRAM Senior Vice President 14 Sylvan Way, Parsippany, NJ 07054 This Disclosure Guide to the RCI Weeks Exchange Program (“Disclosure Guide”) explains the RCI Weeks Elizabeth Dreyer Exchange Program offered to Vacation Owners by RCI, Senior Vice President, Chief Accounting Officer, and LLC (“RCI”). Vacation Owners should carefully review Manager this information to ensure full understanding of the 6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, FL 32821 terms, conditions, operation and use of the RCI Weeks Exchange Program. Note: Unless otherwise stated Julia A. Frey herein, capitalized terms in this Disclosure Guide have the Assistant Secretary same meaning as those in the Terms and Conditions of 6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, FL 32821 RCI Weeks Subscribing Membership, which are made a part of this document. Brian Gray Vice President RCI is the owner and operator of the RCI Weeks 6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, FL 32821 Exchange Program. No government agency has approved the merits of this exchange program. Gary Green Senior Vice President RCI is a Delaware limited liability company (registered as 6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, FL 32821 Resort Condominiums -

A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences 2010 The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World" (2010). Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard. 20. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans/20 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 200 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World Paul A. Johnsgard Pages xvii–xxiii: recent taxonomic changes, I have revised sev- Introduction to the Family Anatidae eral of the range maps to conform with more current information. For these updates I have Since the 978 publication of my Ducks, Geese relied largely on Kear (2005). and Swans of the World hundreds if not thou- Other important waterfowl books published sands of publications on the Anatidae have since 978 and covering the entire waterfowl appeared, making a comprehensive literature family include an identification guide to the supplement and text updating impossible. -

51 20 Sommerfaltkarte EN.Indd

Want to see the towns and villages on the map? Please turn over! 1 Good to know 2 Region & people 1.1 Tourism Boards Long-distance hiking MTB Climbing Families X 1.2 Travelling to Tirol 2.1 Tirol‘s Mountains XX 2.3 Food & Drink Telephone number & Towns and villages in this region e-mail address Webseite Region good for ARRIVING BY TRAIN coming from Switzerland Tirol is a land of mountains, home to more than 500 summits International Intercity via St. Anton am Arlberg. over 3,000 metres. The northern part of Tirol is dominated by 1 Achensee Tourismus Achenkirch, Maurach, Pertisau, +43.5246.5300-0 www.achensee.com trains run by the ÖBB Drivers using Austrian the Northern Limestone Alps, which include the Wetterstein Steinberg am Rofan [email protected] (Austrian Federal Rail- motorways must pay a and Kaiser Mountains, the Brandenberg and Lechtal Alps, the ways) are a comfortable way toll charge. Toll stickers Karwendel Mountains and the Mieming Mountains. The Sou- 2 Alpbachtal Alpbach, Brandenberg, Breitenbach am Inn, +43.5337.21200 www.alpbachtal.at to get to Tirol. The central (Vignetten) can be bought Brixlegg, Kramsach, Kundl, Münster, Radfeld, [email protected] thern Limestone Alps run along the borders with Carinthia Rattenberg, Reith im Alpbachtal train station in Innsbruck from Austrian automobile and Italy. They comprise the Carnic and Gailtal Alps as well serves as an important hub associations as well as at as the Lienz Dolomites. The Limestone Alps were formed long 3 Erste Ferienregion Aschau, Bruck am Ziller, Fügen, Fügenberg, +43.5288.62262 www.best-of-zillertal.at im Zillertal Gerlos, Hart, Hippach, Hochfügen, Kaltenbach, [email protected] and so do the stations at petrol stations and border ago by sediments of an ancient ocean.