An Examination of the Relationships Between Ethnicity, Acculturation, and Attitudes to Places and Their Products

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ethnic Identity, Consumer Ethnocentrism, and Purchase Intentions Among Bi-Cultural Ethnic Consumers: "Divided Loyalties" Or “Dual Allegiance”?

Ethnic identity, consumer ethnocentrism, and purchase intentions among bi-cultural ethnic consumers: "Divided loyalties" or “dual allegiance”? for Journal of Business Research Dr. Michel Laroche, Editor by Dr. Alia El Banna, Senior Lecturer 1, * Dr. Nicolas Papadopoulos, Chancellor's Professor 2 Dr. Steven A. Murphy, Professor 3 Dr. Michel Rod, Professor 2 Dr. José I. Rojas-Méndez, Professor 2 1 University of Bedfordshire Business School University Square, Bedfordshire, LU1 3JU, UK 2 Eric Sprott School of Business, Carleton University 1125 Colonel By Drive, Ottawa, Canada K1S 5B6 3 Ted Rogers School of Business, Ryerson University 350 Victoria Street, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5B 2K3 * Corresponding author Dr. Alia El Banna Senior Lecturer Department of International Business, Marketing, and Tourism University of Bedfordshire Business School University Square, Bedfordshire, LU1 3JU, UK Phone: +44 (0) 1582 489363 Email: [email protected] 1 Ethnic identity, consumer ethnocentrism, and purchase intentions among bi-cultural ethnic consumers: “Divided loyalties" or “dual allegiance”? ABSTRACT Consumer ethnocentrism has been studied extensively in international marketing in the context of one's country of residence. This paper investigates for the first time the notion of "dual ethnocentrism", which may be encountered among ethnic consumers who have an allegiance toward, or divided loyalties between, two countries: One with which they are ethnically linked, or "home", and one where they presently live and work, or "host". The study examines the relationship between ethnic identity, dual ethnocentrism, and purchase intentions among ethnic consumers, a market segment of growing importance in research and practice. The analysis focuses on differences in the respondents' home- and host-related ethnocentrism and finds that indeed ethnocentric feelings and their effects differ depending on the country of reference. -

Appendix 6 Board of Directors’ Response to the Recommendations Presented in the Ombudsmens’ Report

APPENDIX 6 BOARD OF DIRECTORS’ RESPONSE TO THE RECOMMENDATIONS PRESENTED IN THE OMBUDSMENS’ REPORT BOARD OF DIRECTORS of the CANADIAN BROADCASTING CORPORATION STANDING COMMITTEES ON ENGLISH AND FRENCH LANGUAGE BROADCASTING Minutes of the Meeting held on June 18, 2014 Ottawa, Ontario = by videoconference Members of the Committee present: Rémi Racine, Chairperson of the Committees Hubert T. Lacroix Edward Boyd Peter Charbonneau George Cooper Pierre Gingras Marni Larkin Terrence Leier Maureen McCaw Brian Mitchell Marlie Oden Members of the Committee absent: Cecil Hawkins In attendance: Maryse Bertrand, Vice-President, Real Estate, Legal Services and General Counsel Heather Conway, Executive Vice-President, English Services () Louis Lalande, Executive Vice-President, French Services () Michel Cormier, Executive Director, News and Current Affairs, French Services () Stéphanie Duquette, Chief of Staff to the President and CEO Esther Enkin, Ombudsman, English Services () Tranquillo Marrocco, Associate Corporate Secretary Jennifer McGuire, General Manage and Editor in Chief, CBC News and Centres, English Services () Pierre Tourangeau, Ombudsman, French Services () Opening of the Meeting At 1:10 p.m., the Chairperson called the meeting to order. 2014-06-18 Broadcasting Committees Page 1 of 2 1. 2013-2014 Annual Report of the English Services’ Ombudsman Esther Enkin provided an overview of the number of complaints received during the fiscal year and the key subject matters raised, which included the controversy about paid speaking engagements by CBC personalities, the reporting on results polls, the style of, and views expressed by, a commentator, questions relating to matters of taste, the coverage regarding the mayor of Toronto, and the website’s section for comments. She also addressed the manner in which non-news and current affairs complaints are being handled by the Corporation. -

Egyptian Canadian Cultural Association of Ottawa Articles Of

ECCAO Articles Of Incorporation Egyptian Canadian Cultural Association of Ottawa Articles of Incorporation Page 1 of 4 ECCAO Articles Of Incorporation Contents 1. The Name of the Corporation: ............................................................................................. 3 2. Address of the Corporation: ................................................................................................. 3 3. The objects for which the Corporations incorporated are: ................................................... 3 4. Restrictions: ......................................................................................................................... 4 5. Membership: ........................................................................................................................ 4 6. Voting Rights: ...................................................................................................................... 4 Page 2 of 4 ECCAO Articles Of Incorporation 1. The Name of the Corporation: 1.1. EGYPTIAN CANADIAN CULTURAL ASSOCIATION OF OTTAWA (ECCAO) 2. Address of the Corporation: 2.1. 2 Swans Way, Gloucester Ontario K1J 6J2 3. The objects for which the Corporations incorporated are: 3.1. To foster the identity of the Egyptian Individual and community in Ottawa: 3.1.1.1.1. Creating programs and activities which provide information about the history and culture of Egypt. 3.1.1.2.2. Create programs and activities utilizing the inherent advantages and strengths of unified ethnic group within the Canadian and North-American -

Page 1 of 27 Curriculum Vitae Department of Political Science

Curriculum Vitae Department of Political Science, University of Waterloo Balsillie School of International Affairs 200 University Avenue W. 67 Erb Street Waterloo, ON Waterloo, ON N2L 3G1 N2L 6C2 PHONE 519-888-4567 x32823 (UW) or 226-772-3110 EMAIL [email protected] WEBSITE www.arts.uwaterloo.ca/~bmomani LANGUAGES English, Arabic, Basic French EDUCATION Ph.D. 2002, University of Western Ontario M.A. 1996, University of Guelph B.A. 1994, University of Toronto CURRENT POSITIONS 2009- Associate Professor, Political Science, University of Waterloo and Balsillie School of International Affairs, Waterloo, Canada. 2005- Senior Fellow, Centre for International Governance and Innovation, Waterloo, Canada. PAST ACADEMIC POSITIONS 2011-2014 Non-Resident Senior Fellow, Brookings Institution, Washington, DC. 2012-2013 Visiting Associate, Georgetown University’s Mortara Research Center, Washington, DC. 2009-2010 Visiting Fellow, Amman Institute 2004-2009 Assistant Professor, University of Waterloo 1998-2004 Adjunct Professor, University of Western Ontario 2002-2003 Lecturer, Wilfrid Laurier University EXPERTISE • Middle Eastern Economies • Middle Eastern Foreign Policies • ‘Arab Spring’ and revolutions in the Middle East • International Financial Institutions • International Political Economy • International Monetary Fund Page 1 of 27 GRANTS, AWARDS, AND HONOURS 2014-2015 IDRC Small Partnership Grant ($12,500) 2014 UBC Scholarly Publication Award ($8,000) 2013-2014 UW Lois Claxton HSS Endowment Fund Award ($7,000) 2013-2014 UW Research Incentive Fund ($8,000) 2012-2013 Fulbright Scholar Award ($12,500) 2013- Nominated for the Arab Ambassadors Award, political category. 2012-2013 UW/SSHRC Seed Grant ($5,000) 2011-2012 UW Research Incentive Fund ($8,000) 2011-2013 UW International Collaboration Grant ($10,000) 2011 Nominated for the Canadian Public Administration’s J.E.H. -

Citizenship Revocation in the Mainstream Press: a Case of Re-Ethni- Cization?

Citizenship RevoCation in the MainstReaM pRess: a Case of Re-ethni- Cization? elke WinteR ivana pRevisiC Abstract. Under the original version of the Strengthening Canadian Citizenship Act (2014), dual citizens having committed high treason, terrorism or espionage could lose their Canadian citizenship. In this paper, we examine how the measure was dis- cussed in Canada’s mainstream newspapers. We ask: who/what is seen as the target of citizenship revocation? What does this tell us about the direction that Canadian more often critical than supportive of the citizenship revocation provision. However, the press ignored the involvement of non-Muslim, white, Western-origin Canadians in terrorist acts and interpreted the measure as one that was mostly affecting Canadian Muslims. Thus, despite advocating for equal citizenship in principle, in their writing and reporting practice, Canadian newspapers constructed Canadian Muslims as sus- picious and less Canadian nonetheless. Keywords: Muslim Canadians; Citizenship; Terrorism; Canada; Revocation Résumé: Au sein de la version originale de la Loi renforçant la citoyenneté cana- dienne (2014), les citoyens canadiens ayant une double citoyenneté et ayant été condamnés pour haute trahison, pour terrorisme ou pour espionnage, auraient pu se faire révoquer leur citoyenneté canadienne. Dans cet article, nous étudions comment ce projet de loi fut discuté au sein de la presse canadienne. Nous cherchons à répondre à deux questions: Qui/quoi est perçu comme pouvant faire l’objet d’une révocation de citoyenneté? En quoi cela nous informe-t-il sur les orientations futures de la citoy- enneté canadienne? Nos résultats démontrent que les journaux canadiens sont plus critiques à l’égard de la révocation de la citoyenneté que positionnés en sa faveur. -

University of Alberta Perception of Climate Change Among Egyptians

University of Alberta Perception of Climate Change Among Egyptians Living in Egypt and Canada By Tarek Ahmed Zaki A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science In Rural Sociology Department of Resources Economics and Environmental Sociology ©Tarek Ahmed Zaki Fall 2011 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-90280-6 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-90280-6 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l'Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. -

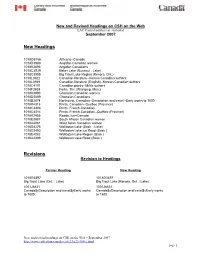

New and Revised Headings on CSH on the Web LAC Control Numbers Are Included September 2007

New and Revised Headings on CSH on the Web LAC Control numbers are included September 2007 New Headings 1018G3756 Africans--Canada 1018D3988 Angolan Canadian women 1018K3893 Angolan Canadians 1018C3539 Baker Lake (Nunavut : Lake) 1018C3555 Big Trout Lake Region (Kenora, Ont.) 1018L3922 Canadian literature--Korean Canadian authors 1018L3949 Canadian literature (English)--Korean Canadian authors 1018C4101 Canadian poetry--Métis authors 1018F3838 Forks, The (Winnipeg, Man.) 1018K3990 Ghanaian Canadian women 1018D3899 Ghanaian Canadians 1018B3874 Northwest, Canadian--Description and travel--Early works to 1800 1018K4318 Prints, Canadian--Québec (Province) 1018C4306 Prints, French-Canadian 1018C4314 Prints, French-Canadian--Québec (Province) 1018K2455 Roads, Ice--Canada 1018E3987 South African Canadian women 1018A4081 West Asian Canadian women 1018D4275 Wollaston Lake (Sask. : Lake) 1018D2493 Wollaston Lake Ice Road (Sask.) 1018E4282 Wollaston Lake Region (Sask.) 1018A2399 Wollaston Lake Road (Sask.) Revisions Revision to Headings Former Heading New Heading 1018G3497 1018G3497 Big Trout Lake (Ont. : Lake) Big Trout Lake (Kenora, Ont. : Lake) 1001J6831 1001J6831 Canada$xDescription and travel$yEarly works Canada$xDescription and travel$vEarly works to 1800 to 1800 New and revised headings on CSH on the Web – September 2007 http://www.collectionscanada.ca/6/23/s23-300-e.html page 1 Revision only to References and/or Notes 1017E5712 Algerian Canadians 1011J2717 Art, French-Canadian--Québec (Province) 0200E4955 Asian Canadians 0200D1167 Canadian -

Citizenship Revocation in the Mainstream Press: a Case of Re-Ethni- Cization?

CITIZENSHIP REVOCATION IN THE MAINSTREAM PRESS: A CASE OF RE-ETHNI- CIZATION? ELKE WINTER IVANA PREVISIC Abstract. Under the original version of the Strengthening Canadian Citizenship Act (2014), dual citizens having committed high treason, terrorism or espionage could lose their Canadian citizenship. In this paper, we examine how the measure was dis- cussed in Canada’s mainstream newspapers. We ask: who/what is seen as the target of citizenship revocation? What does this tell us about the direction that Canadian citizenship is moving towards? Our findings show that Canadian newspapers were more often critical than supportive of the citizenship revocation provision. However, the press ignored the involvement of non-Muslim, white, Western-origin Canadians in terrorist acts and interpreted the measure as one that was mostly affecting Canadian Muslims. Thus, despite advocating for equal citizenship in principle, in their writing and reporting practice, Canadian newspapers constructed Canadian Muslims as sus- picious and less Canadian nonetheless. Keywords: Muslim Canadians; Citizenship; Terrorism; Canada; Revocation Résumé: Au sein de la version originale de la Loi renforçant la citoyenneté cana- dienne (2014), les citoyens canadiens ayant une double citoyenneté et ayant été condamnés pour haute trahison, pour terrorisme ou pour espionnage, auraient pu se faire révoquer leur citoyenneté canadienne. Dans cet article, nous étudions comment ce projet de loi fut discuté au sein de la presse canadienne. Nous cherchons à répondre à deux questions: Qui/quoi est perçu comme pouvant faire l’objet d’une révocation de citoyenneté? En quoi cela nous informe-t-il sur les orientations futures de la citoy- enneté canadienne? Nos résultats démontrent que les journaux canadiens sont plus critiques à l’égard de la révocation de la citoyenneté que positionnés en sa faveur. -

1 Title: Old Country Passions

1 Title: Old Country Passions: An International Examination of Country Image, Animosity, and Affinity among Ethnic Consumers Abstract: Ethnic consumers are an important market segment in both traditionally multicultural countries as well as newer recipients of growing immigration movements. Such consumers may carry with them views toward "old friends and foes" which may influence their attitudes toward the products of countries perceived as friendly or hostile in relation to their original home countries. This study examines together for the first time four place-related constructs, namely, country and people images, product images, affinity, and animosity, and their potential effects on purchase intentions, juxtaposing these measures against views toward countries that may be perceived as friendly or hostile from the perspective of the ethnic consumers' homeland, alongside a neutral "benchmark" country for comparison. The results show that country/people and product images, affinity, and animosity work differently depending on the target country, product and people evaluations are influenced by both affective and cognitive factors, and attitudes vary in their predictive ability on purchase intentions, sometimes in line with earlier findings and sometimes not. Implications and directions for future research are discussed. Keywords: Country image, Animosity, Affinity, Ethnic consumers 2 INTRODUCTION The influx of immigrants and refugees in host countries over the past few decades, and their potential as significant markets, makes it vital to understand ethnic consumers' consumption- related behaviours. For instance, in his review of the relevant literature Cui (2001) noted that three ethnic groups in the U.S. (African, Asian, and Hispanic Americans) represent 25% of the population and account for a trillion-dollar growth market. -

An Examination of the Relationships Between Ethnicity, Acculturation, and Attitudes to Places and Their Products

An Examination of the Relationships between Ethnicity, Acculturation, and Attitudes to Places and their Products By Alia R. El Banna A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Management Sprott School of Business Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2014 Alia R. El Banna i Abstract Ethnic consumers' "dual allegiance" to their ethnic affiliation and residence countries raises unique research opportunities to examine the role of ethnicity and acculturation in product and place buyer behaviour in the context of research on product country image and place constructs. This study examines ethnic consumers' place and product evaluations in a complex framework that combines multiple cultural, social, and marketing concepts. This research centres on the idea that ethnic individuals who decide to migrate from their country of origin to host countries, or who are born in a host country to immigrant parents, are affiliated with two places that may or may not be aligned economically, politically, or culturally. Therefore, ethnic individuals could possibly be tagged in two directions depending on their ethnicity and acculturative tendency. The principal compelling element in this study, which comprises its main intended contribution, is consumers’ identification with the notions of “home” and “host” countries in an ethnic context, and the forces that influence their relationship with places and their offerings. The main proposition of the research is, therefore, set to systematically investigate the extent to which consumers’ ethnic strength with their country of origin, and the degree of their acculturation to the host culture, both influence their evaluations and willingness to buy products that originate from countries that are expected to be viewed negatively or positively by them. -

Engaging Ethnocultural Communities on Hepatitis C Partpart IVII

Engaging Ethnocultural Communities on Hepatitis C PartPart IVII Canadian Liver Foundation and Canadian Ethnocultural Council Final Report March 31, 2009 Engaging Ethnocultural Communities on Hepatitis C Part IV Prepared by: Canadian Liver Foundation and Canadian Ethnocultural Council Submitted to: Hepatitis C Prevention, Support, and Research Program Public Health Agency of Canada Final Report March 31, 2009 Engaging Ethnocultural Communities on Hepatitis C - Part IV Table of Contents 1.0 Executive Summary .......................................................................................................... 1 2.0 Background ....................................................................................................................... 7 2.1 Partners ....................................................................................................................... 7 2.1.1 Canadian Liver Foundation (CLF) .................................................................. 7 2.1.2 Canadian Ethnocultural Council (CEC) .......................................................... 7 2.2 Hepatitis C .................................................................................................................. 8 2.2.1 About Hepatitis C ........................................................................................... 8 2.2.2 Hepatitis C in Ethnocultural Communities in Canada .................................... 9 2.3 Engaging Ethnocultural Communities on Hepatitis C – Part I ..................................10 2.4 Engaging -

The Relationship Between Parenting Styles, Acculturation, Individuation, and Mental Health in Arab American Adults

University of Central Florida STARS HIM 1990-2015 2014 The Relationship Between Parenting Styles, Acculturation, Individuation, and Mental Health in Arab American Adults Mira Atia University of Central Florida Part of the Psychology Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses1990-2015 University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIM 1990-2015 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Atia, Mira, "The Relationship Between Parenting Styles, Acculturation, Individuation, and Mental Health in Arab American Adults" (2014). HIM 1990-2015. 1631. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses1990-2015/1631 THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN PARENTING STYLES, ACCULTURATION, INDIVIDUATION, AND MENTAL HEALTH IN ARAB AMERICAN ADULTS By MIRA ATIA A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Major Program in Psychology in the College of Sciences and in The Burnett Honors College at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Summer Term 2014 Thesis Chair: Dr. Bernard Jensen ABSTRACT Parents are among the important socialization agents that influence the persons we become. Previous research (Baumrind, 1967; 1972; 1991; 1987) has identified three primary parenting styles: permissive, authoritative, and authoritarian, and a large amount of research has investigated the long term implications of these styles. The current study aimed to investigate the universality of these parenting styles, in particular, among Arab American Adults (N =22). The study examined the relationships between overall mental health and parenting styles, acculturation, and individuation in this population.