1 Title: Old Country Passions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Influence of Terrorism on Discriminatory Attitudes and Behaviors

Shades of Intolerance: The Influence of Terrorism on Discriminatory Attitudes and Behaviors in the United Kingdom and Canada. by Chuck Baker A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Global Affairs Written under the direction of Dr. Gregg Van Ryzin and approved by ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ Newark, New Jersey May, 2015 Copyright page: © 2015 Chuck Baker All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The Influence of Terrorism on Discriminatory Attitudes and Behaviors in the United Kingdom and Canada by Chuck Baker Dissertation Director: Dr. Gregg Van Ryzin, Ph.D. Terrorism has been shown to have a destabilizing impact upon the citizens of the nation- state in which it occurs, causing social distress, fear, and the desire for retribution (Cesari, 2010; Chebel d’Appollonia, 2012). Much of the recent work on 21st century terrorism carried out in the global north has placed the focus on terrorism being perpetuated by Middle East Muslims. In addition, recent migration trends show that the global north is becoming much more diverse as the highly populated global south migrates upward. Population growth in the global north is primarily due to increases in the minority presence, and these post-1960 changes have increased the diversity of historically more homogeneous nations like the United Kingdom and Canada. This research examines the influence of terrorism on discriminatory attitudes and behaviors, with a focus on the United Kingdom in the aftermath of the July 7, 2005 terrorist attacks in London. -

Ethnic Identity, Consumer Ethnocentrism, and Purchase Intentions Among Bi-Cultural Ethnic Consumers: "Divided Loyalties" Or “Dual Allegiance”?

Ethnic identity, consumer ethnocentrism, and purchase intentions among bi-cultural ethnic consumers: "Divided loyalties" or “dual allegiance”? for Journal of Business Research Dr. Michel Laroche, Editor by Dr. Alia El Banna, Senior Lecturer 1, * Dr. Nicolas Papadopoulos, Chancellor's Professor 2 Dr. Steven A. Murphy, Professor 3 Dr. Michel Rod, Professor 2 Dr. José I. Rojas-Méndez, Professor 2 1 University of Bedfordshire Business School University Square, Bedfordshire, LU1 3JU, UK 2 Eric Sprott School of Business, Carleton University 1125 Colonel By Drive, Ottawa, Canada K1S 5B6 3 Ted Rogers School of Business, Ryerson University 350 Victoria Street, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5B 2K3 * Corresponding author Dr. Alia El Banna Senior Lecturer Department of International Business, Marketing, and Tourism University of Bedfordshire Business School University Square, Bedfordshire, LU1 3JU, UK Phone: +44 (0) 1582 489363 Email: [email protected] 1 Ethnic identity, consumer ethnocentrism, and purchase intentions among bi-cultural ethnic consumers: “Divided loyalties" or “dual allegiance”? ABSTRACT Consumer ethnocentrism has been studied extensively in international marketing in the context of one's country of residence. This paper investigates for the first time the notion of "dual ethnocentrism", which may be encountered among ethnic consumers who have an allegiance toward, or divided loyalties between, two countries: One with which they are ethnically linked, or "home", and one where they presently live and work, or "host". The study examines the relationship between ethnic identity, dual ethnocentrism, and purchase intentions among ethnic consumers, a market segment of growing importance in research and practice. The analysis focuses on differences in the respondents' home- and host-related ethnocentrism and finds that indeed ethnocentric feelings and their effects differ depending on the country of reference. -

Cross-National Study on the Perception of the Korean Wave and Cultural Hybridity in Indonesia and Malaysia Using Discourse on Social Media

sustainability Article Cross-National Study on the Perception of the Korean Wave and Cultural Hybridity in Indonesia and Malaysia Using Discourse on Social Media Yu Lim Lee 1, Minji Jung 1, Robert Jeyakumar Nathan 2 and Jae-Eun Chung 1,* 1 Department of Consumer Science, Sungkyunkwan University, Sungkyunkwan-ro 25-2, Jongno-gu, Seoul 03063, Korea; [email protected] (Y.L.L.); [email protected] (M.J.) 2 Faculty of Business, Multimedia University, Melaka 75450, Malaysia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-2-760-0508 Received: 25 June 2020; Accepted: 24 July 2020; Published: 28 July 2020 Abstract: In the era of globalization, due to the prevalent cultural exchange between countries, inflows of foreign cultural products can enrich local culture by hybridizing local and global culture together. Although there have been numerous studies on cultural hybridity using qualitative interviews with recipients of foreign cultural products in single countries, cross-national studies that examine the national characteristics that facilitate or impede cultural hybridity remain scarce. The purpose of the present study is to identify the factors that promote or hinder cultural hybridity between the Korean Wave and Muslim culture by probing the similarities and differences in social media data on Korean cultural products between Indonesia and Malaysia using a semantic network analysis. The results of the study uncovered the three factors that promote cultural hybridity (‘Asian identity’, policies emphasizing ‘unity in ethnic diversity’, and ‘local consumers xenocentrism’) and the two hindering elements (‘a conservative nature of religion’ and ‘discrimination between ethnic groups’). Theoretical contributions and practical implications are also provided for promoting cultural hybridity. -

Appendix 6 Board of Directors’ Response to the Recommendations Presented in the Ombudsmens’ Report

APPENDIX 6 BOARD OF DIRECTORS’ RESPONSE TO THE RECOMMENDATIONS PRESENTED IN THE OMBUDSMENS’ REPORT BOARD OF DIRECTORS of the CANADIAN BROADCASTING CORPORATION STANDING COMMITTEES ON ENGLISH AND FRENCH LANGUAGE BROADCASTING Minutes of the Meeting held on June 18, 2014 Ottawa, Ontario = by videoconference Members of the Committee present: Rémi Racine, Chairperson of the Committees Hubert T. Lacroix Edward Boyd Peter Charbonneau George Cooper Pierre Gingras Marni Larkin Terrence Leier Maureen McCaw Brian Mitchell Marlie Oden Members of the Committee absent: Cecil Hawkins In attendance: Maryse Bertrand, Vice-President, Real Estate, Legal Services and General Counsel Heather Conway, Executive Vice-President, English Services () Louis Lalande, Executive Vice-President, French Services () Michel Cormier, Executive Director, News and Current Affairs, French Services () Stéphanie Duquette, Chief of Staff to the President and CEO Esther Enkin, Ombudsman, English Services () Tranquillo Marrocco, Associate Corporate Secretary Jennifer McGuire, General Manage and Editor in Chief, CBC News and Centres, English Services () Pierre Tourangeau, Ombudsman, French Services () Opening of the Meeting At 1:10 p.m., the Chairperson called the meeting to order. 2014-06-18 Broadcasting Committees Page 1 of 2 1. 2013-2014 Annual Report of the English Services’ Ombudsman Esther Enkin provided an overview of the number of complaints received during the fiscal year and the key subject matters raised, which included the controversy about paid speaking engagements by CBC personalities, the reporting on results polls, the style of, and views expressed by, a commentator, questions relating to matters of taste, the coverage regarding the mayor of Toronto, and the website’s section for comments. She also addressed the manner in which non-news and current affairs complaints are being handled by the Corporation. -

Making the Connection Between Social Media and Intercultural Technical Communication Laura Anne Ewing University of South Florida, [email protected]

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 11-16-2015 #networkedglobe: Making the Connection between Social Media and Intercultural Technical Communication Laura Anne Ewing University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Higher Education and Teaching Commons, Other Communication Commons, and the Rhetoric Commons Scholar Commons Citation Ewing, Laura Anne, "#networkedglobe: Making the Connection between Social Media and Intercultural Technical Communication" (2015). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/5945 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. #networkedglobe: Making the Connection between Social Media and Intercultural Technical Communication by Laura Anne Ewing A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Meredith Johnson, Ph.D. Marc Santos, Ph.D. Nathan Johnson, Ph.D. Julie Staggers, Ph.D. Date of Approval November 18, 2015 Keywords: Pedagogy, Engagement, Japan, Higher Education, Taxonomy Copyright (c) 2015, Laura Anne Ewing Dedication For Joe, because the greatest challenges cannot be accomplished without unwavering support, inspiration, and a beer. For Tom, you are my motivation for all things. May you never stop exploring the world. わたしは、あなたを愛しています。 Acknowledgments This project could not have come to fruition without a team of support that stretched 7,000 miles. -

Egyptian Canadian Cultural Association of Ottawa Articles Of

ECCAO Articles Of Incorporation Egyptian Canadian Cultural Association of Ottawa Articles of Incorporation Page 1 of 4 ECCAO Articles Of Incorporation Contents 1. The Name of the Corporation: ............................................................................................. 3 2. Address of the Corporation: ................................................................................................. 3 3. The objects for which the Corporations incorporated are: ................................................... 3 4. Restrictions: ......................................................................................................................... 4 5. Membership: ........................................................................................................................ 4 6. Voting Rights: ...................................................................................................................... 4 Page 2 of 4 ECCAO Articles Of Incorporation 1. The Name of the Corporation: 1.1. EGYPTIAN CANADIAN CULTURAL ASSOCIATION OF OTTAWA (ECCAO) 2. Address of the Corporation: 2.1. 2 Swans Way, Gloucester Ontario K1J 6J2 3. The objects for which the Corporations incorporated are: 3.1. To foster the identity of the Egyptian Individual and community in Ottawa: 3.1.1.1.1. Creating programs and activities which provide information about the history and culture of Egypt. 3.1.1.2.2. Create programs and activities utilizing the inherent advantages and strengths of unified ethnic group within the Canadian and North-American -

Page 1 of 27 Curriculum Vitae Department of Political Science

Curriculum Vitae Department of Political Science, University of Waterloo Balsillie School of International Affairs 200 University Avenue W. 67 Erb Street Waterloo, ON Waterloo, ON N2L 3G1 N2L 6C2 PHONE 519-888-4567 x32823 (UW) or 226-772-3110 EMAIL [email protected] WEBSITE www.arts.uwaterloo.ca/~bmomani LANGUAGES English, Arabic, Basic French EDUCATION Ph.D. 2002, University of Western Ontario M.A. 1996, University of Guelph B.A. 1994, University of Toronto CURRENT POSITIONS 2009- Associate Professor, Political Science, University of Waterloo and Balsillie School of International Affairs, Waterloo, Canada. 2005- Senior Fellow, Centre for International Governance and Innovation, Waterloo, Canada. PAST ACADEMIC POSITIONS 2011-2014 Non-Resident Senior Fellow, Brookings Institution, Washington, DC. 2012-2013 Visiting Associate, Georgetown University’s Mortara Research Center, Washington, DC. 2009-2010 Visiting Fellow, Amman Institute 2004-2009 Assistant Professor, University of Waterloo 1998-2004 Adjunct Professor, University of Western Ontario 2002-2003 Lecturer, Wilfrid Laurier University EXPERTISE • Middle Eastern Economies • Middle Eastern Foreign Policies • ‘Arab Spring’ and revolutions in the Middle East • International Financial Institutions • International Political Economy • International Monetary Fund Page 1 of 27 GRANTS, AWARDS, AND HONOURS 2014-2015 IDRC Small Partnership Grant ($12,500) 2014 UBC Scholarly Publication Award ($8,000) 2013-2014 UW Lois Claxton HSS Endowment Fund Award ($7,000) 2013-2014 UW Research Incentive Fund ($8,000) 2012-2013 Fulbright Scholar Award ($12,500) 2013- Nominated for the Arab Ambassadors Award, political category. 2012-2013 UW/SSHRC Seed Grant ($5,000) 2011-2012 UW Research Incentive Fund ($8,000) 2011-2013 UW International Collaboration Grant ($10,000) 2011 Nominated for the Canadian Public Administration’s J.E.H. -

Citizenship Revocation in the Mainstream Press: a Case of Re-Ethni- Cization?

Citizenship RevoCation in the MainstReaM pRess: a Case of Re-ethni- Cization? elke WinteR ivana pRevisiC Abstract. Under the original version of the Strengthening Canadian Citizenship Act (2014), dual citizens having committed high treason, terrorism or espionage could lose their Canadian citizenship. In this paper, we examine how the measure was dis- cussed in Canada’s mainstream newspapers. We ask: who/what is seen as the target of citizenship revocation? What does this tell us about the direction that Canadian more often critical than supportive of the citizenship revocation provision. However, the press ignored the involvement of non-Muslim, white, Western-origin Canadians in terrorist acts and interpreted the measure as one that was mostly affecting Canadian Muslims. Thus, despite advocating for equal citizenship in principle, in their writing and reporting practice, Canadian newspapers constructed Canadian Muslims as sus- picious and less Canadian nonetheless. Keywords: Muslim Canadians; Citizenship; Terrorism; Canada; Revocation Résumé: Au sein de la version originale de la Loi renforçant la citoyenneté cana- dienne (2014), les citoyens canadiens ayant une double citoyenneté et ayant été condamnés pour haute trahison, pour terrorisme ou pour espionnage, auraient pu se faire révoquer leur citoyenneté canadienne. Dans cet article, nous étudions comment ce projet de loi fut discuté au sein de la presse canadienne. Nous cherchons à répondre à deux questions: Qui/quoi est perçu comme pouvant faire l’objet d’une révocation de citoyenneté? En quoi cela nous informe-t-il sur les orientations futures de la citoy- enneté canadienne? Nos résultats démontrent que les journaux canadiens sont plus critiques à l’égard de la révocation de la citoyenneté que positionnés en sa faveur. -

University of Alberta Perception of Climate Change Among Egyptians

University of Alberta Perception of Climate Change Among Egyptians Living in Egypt and Canada By Tarek Ahmed Zaki A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science In Rural Sociology Department of Resources Economics and Environmental Sociology ©Tarek Ahmed Zaki Fall 2011 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-90280-6 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-90280-6 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l'Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. -

WHAT's WRONG with the SOCIAL SCIENCES? the Perils of the Postmodern

WHAT'S WRONG WITH THE SOCIAL SCIENCES? The Perils of the Postmodern Michael A. Faia College of William & Mary 1993 For Caitlin, Josephine, Gusty, and Pancho Et si je connais, moi, une fleur unique au monde, qui n'existe nulle part, sauf dans ma planète, et qu'un petit mouton peut anéantir d'un seul coup, comme ça, un matin, sans se rendre compte de ce qu'il fait, ce n'est pas important ça! —Antoine de Saint-Exupéry iii Table of Contents Introduction Chapter 1: WHAT'S WRONG WITH THE SOCIAL SCIENCES? 1 (1) The dialectics of disenchantment 2 (1.1) Predictability, vulcanology, seismology, and (especially) meteorology 6 (1.2) Molecular mysteries and habits of the quark 8 (1.3) Rosaldo revisited: How would the catcher in the rye have felt? 12 (2) The trouble with feminist theory 13 (3) Titles and tribulations 17 (4) Solicitous gatekeepers, #1 25 (5) Itching and scratching: a Lazarsfeldian digression through an SPSS 27 hologram (6) Transcending the transcendentalists 30 (7) What do you presuppose, and when did you presuppose it? The Sisyphus of the social sciences 33 (8) The meaning of politics and the politics of meaning 38 Chapter 2: MICHEL FOUCAULT, MACHINES WHO THINK, AND THE HUMAN SCIENCES 57 (1) “Man the machine—man the impersonal engine” 57 (2) Good, bad, or ugly? 67 (3) Mitigating circumstances 70 iv (4) In conclusion: Oodles of Boodles 74 (5) Why Foucault needed Lindroth, and why Lindroth needed Foucault 75 Chapter 3: IN PRAISE OF THE NULL HYPOTHESIS: THE MYTH OF “THE VALUE-FREE MYTH” 83 (1) The nature and extent of bias in scientific research 83 (2) Quashing the indictment: Can a Comtean rule a country? 85 (2.1) Positions 86 (2.2) Correctives 87 (2.3) Motives: A series of acts contrary .. -

Consumer Xenocentrism: Antecedents, Consequences (And Moderators) and Related Constructs

Consumer Xenocentrism: Antecedents, consequences (and moderators) and related constructs by Dhanachitra Rettanai Kannan A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Management Carleton University, Ottawa, Ontario ©2020 Dhanachitra Rettanai Kannan Abstract Purpose: The purpose of this thesis is to identify and test the antecedents, related constructs and consequences and moderators of consumers xenocentrism. Design/methodology/approach: An extensive literature review was performed across different disciplines (international business, economics, sociology, psychology, political science, anthropology and consumer behavior) and interviews with five different experts from the five different fields were conducted to put together the initial model. A combined sample of 1306 respondents from four different countries namely Kenya, India, Ecuador and Romania in four different continents Africa, Asia, South America and Europe were collected through online questionnaires. The data was analyzed using structural equation modeling (SEM) to either confirm or disprove the hypotheses that had been set. Findings: International travel experience, status consumption and susceptibility to normative influence were the most significant antecedents that positively influenced consumer xenocentrism. Culture (power distance and collectivism) had an indirect positive influence on consumer xenocentrism through the consumption-specific constructs, status consumption and susceptibility to normative influence respectively. With respect to related constructs, consumer worldmindedness was positively significantly related to consumer xenocentrism and consumer ethnocentrism and national identity were negatively ii significantly related to consumer xenocentrism. With respect to the consequences’ variables, consumer xenocentrism positively influenced ownership (actual purchase) of foreign products and purchase intention of foreign products. -

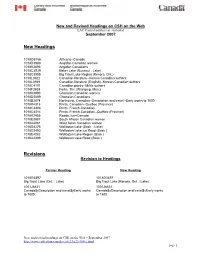

New and Revised Headings on CSH on the Web LAC Control Numbers Are Included September 2007

New and Revised Headings on CSH on the Web LAC Control numbers are included September 2007 New Headings 1018G3756 Africans--Canada 1018D3988 Angolan Canadian women 1018K3893 Angolan Canadians 1018C3539 Baker Lake (Nunavut : Lake) 1018C3555 Big Trout Lake Region (Kenora, Ont.) 1018L3922 Canadian literature--Korean Canadian authors 1018L3949 Canadian literature (English)--Korean Canadian authors 1018C4101 Canadian poetry--Métis authors 1018F3838 Forks, The (Winnipeg, Man.) 1018K3990 Ghanaian Canadian women 1018D3899 Ghanaian Canadians 1018B3874 Northwest, Canadian--Description and travel--Early works to 1800 1018K4318 Prints, Canadian--Québec (Province) 1018C4306 Prints, French-Canadian 1018C4314 Prints, French-Canadian--Québec (Province) 1018K2455 Roads, Ice--Canada 1018E3987 South African Canadian women 1018A4081 West Asian Canadian women 1018D4275 Wollaston Lake (Sask. : Lake) 1018D2493 Wollaston Lake Ice Road (Sask.) 1018E4282 Wollaston Lake Region (Sask.) 1018A2399 Wollaston Lake Road (Sask.) Revisions Revision to Headings Former Heading New Heading 1018G3497 1018G3497 Big Trout Lake (Ont. : Lake) Big Trout Lake (Kenora, Ont. : Lake) 1001J6831 1001J6831 Canada$xDescription and travel$yEarly works Canada$xDescription and travel$vEarly works to 1800 to 1800 New and revised headings on CSH on the Web – September 2007 http://www.collectionscanada.ca/6/23/s23-300-e.html page 1 Revision only to References and/or Notes 1017E5712 Algerian Canadians 1011J2717 Art, French-Canadian--Québec (Province) 0200E4955 Asian Canadians 0200D1167 Canadian