ARI Projects Arab Securitocracies and Security Sector Reform

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Christians and Jews in Muslim Societies

Arabic and its Alternatives Christians and Jews in Muslim Societies Editorial Board Phillip Ackerman-Lieberman (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, USA) Bernard Heyberger (EHESS, Paris, France) VOLUME 5 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/cjms Arabic and its Alternatives Religious Minorities and Their Languages in the Emerging Nation States of the Middle East (1920–1950) Edited by Heleen Murre-van den Berg Karène Sanchez Summerer Tijmen C. Baarda LEIDEN | BOSTON Cover illustration: Assyrian School of Mosul, 1920s–1930s; courtesy Dr. Robin Beth Shamuel, Iraq. This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Murre-van den Berg, H. L. (Hendrika Lena), 1964– illustrator. | Sanchez-Summerer, Karene, editor. | Baarda, Tijmen C., editor. Title: Arabic and its alternatives : religious minorities and their languages in the emerging nation states of the Middle East (1920–1950) / edited by Heleen Murre-van den Berg, Karène Sanchez, Tijmen C. Baarda. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, 2020. | Series: Christians and Jews in Muslim societies, 2212–5523 ; vol. -

By Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Of

FROM DIWAN TO PALACE: JORDANIAN TRIBAL POLITICS AND ELECTIONS by LAURA C. WEIR Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Adviser: Dr. Pete Moore Department of Political Science CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY January, 2013 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of Laura Weir candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree *. Pete Moore, Ph.D (chair of the committee) Vincent E. McHale, Ph.D. Kelly McMann, Ph.D. Neda Zawahri, Ph.D. (date) October 19, 2012 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables v List of Maps and Illustrations viii List of Abbreviations x CHAPTERS 1. RESEARCH PUZZLE AND QUESTIONS Introduction 1 Literature Review 6 Tribal Politics and Elections 11 Case Study 21 Potential Challenges of the Study 30 Conclusion 35 2. THE HISTORY OF THE JORDANIAN ―STATE IN SOCIETY‖ Introduction 38 The First Wave: Early Development, pre-1921 40 The Second Wave: The Arab Revolt and the British, 1921-1946 46 The Third Wave: Ideological and Regional Threats, 1946-1967 56 The Fourth Wave: The 1967 War and Black September, 1967-1970 61 Conclusion 66 3. SCARCE RESOURCES: THE STATE, TRIBAL POLITICS, AND OPPOSITION GROUPS Introduction 68 How Tribal Politics Work 71 State Institutions 81 iii Good Governance Challenges 92 Guests in Our Country: The Palestinian Jordanians 101 4. THREATS AND OPPORTUNITIES: FAILURE OF POLITICAL PARTIES AND THE RISE OF TRIBAL POLITICS Introduction 118 Political Threats and Opportunities, 1921-1970 125 The Political Significance of Black September 139 Tribes and Parties, 1989-2007 141 The Muslim Brotherhood 146 Conclusion 152 5. -

The Migration of Indians to Eastern Africa: a Case Study of the Ismaili Community, 1866-1966

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2019 The Migration of Indians to Eastern Africa: A Case Study of the Ismaili Community, 1866-1966 Azizeddin Tejpar University of Central Florida Part of the African History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Tejpar, Azizeddin, "The Migration of Indians to Eastern Africa: A Case Study of the Ismaili Community, 1866-1966" (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 6324. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/6324 THE MIGRATION OF INDIANS TO EASTERN AFRICA: A CASE STUDY OF THE ISMAILI COMMUNITY, 1866-1966 by AZIZEDDIN TEJPAR B.A. Binghamton University 1971 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2019 Major Professor: Yovanna Pineda © 2019 Azizeddin Tejpar ii ABSTRACT Much of the Ismaili settlement in Eastern Africa, together with several other immigrant communities of Indian origin, took place in the late nineteenth century and early twentieth centuries. This thesis argues that the primary mover of the migration were the edicts, or Farmans, of the Ismaili spiritual leader. They were instrumental in motivating Ismailis to go to East Africa. -

Table 1 Comprehensive International Points List

Table 1 Comprehensive International Points List FCC ITU-T Country Region Dialing FIPS Comments, including other 1 Code Plan Code names commonly used Abu Dhabi 5 971 TC include with United Arab Emirates Aden 5 967 YE include with Yemen Admiralty Islands 7 675 PP include with Papua New Guinea (Bismarck Arch'p'go.) Afars and Assas 1 253 DJ Report as 'Djibouti' Afghanistan 2 93 AF Ajman 5 971 TC include with United Arab Emirates Akrotiri Sovereign Base Area 9 44 AX include with United Kingdom Al Fujayrah 5 971 TC include with United Arab Emirates Aland 9 358 FI Report as 'Finland' Albania 4 355 AL Alderney 9 44 GK Guernsey (Channel Islands) Algeria 1 213 AG Almahrah 5 967 YE include with Yemen Andaman Islands 2 91 IN include with India Andorra 9 376 AN Anegada Islands 3 1 VI include with Virgin Islands, British Angola 1 244 AO Anguilla 3 1 AV Dependent territory of United Kingdom Antarctica 10 672 AY Includes Scott & Casey U.S. bases Antigua 3 1 AC Report as 'Antigua and Barbuda' Antigua and Barbuda 3 1 AC Antipodes Islands 7 64 NZ include with New Zealand Argentina 8 54 AR Armenia 4 374 AM Aruba 3 297 AA Part of the Netherlands realm Ascension Island 1 247 SH Ashmore and Cartier Islands 7 61 AT include with Australia Atafu Atoll 7 690 TL include with New Zealand (Tokelau) Auckland Islands 7 64 NZ include with New Zealand Australia 7 61 AS Australian External Territories 7 672 AS include with Australia Austria 9 43 AU Azerbaijan 4 994 AJ Azores 9 351 PO include with Portugal Bahamas, The 3 1 BF Bahrain 5 973 BA Balearic Islands 9 34 SP include -

List of Certain Foreign Institutions Classified As Official for Purposes of Reporting on the Treasury International Capital (TIC) Forms

NOT FOR PUBLICATION DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY JANUARY 2001 Revised Aug. 2002, May 2004, May 2005, May/July 2006, June 2007 List of Certain Foreign Institutions classified as Official for Purposes of Reporting on the Treasury International Capital (TIC) Forms The attached list of foreign institutions, which conform to the definition of foreign official institutions on the Treasury International Capital (TIC) Forms, supersedes all previous lists. The definition of foreign official institutions is: "FOREIGN OFFICIAL INSTITUTIONS (FOI) include the following: 1. Treasuries, including ministries of finance, or corresponding departments of national governments; central banks, including all departments thereof; stabilization funds, including official exchange control offices or other government exchange authorities; and diplomatic and consular establishments and other departments and agencies of national governments. 2. International and regional organizations. 3. Banks, corporations, or other agencies (including development banks and other institutions that are majority-owned by central governments) that are fiscal agents of national governments and perform activities similar to those of a treasury, central bank, stabilization fund, or exchange control authority." Although the attached list includes the major foreign official institutions which have come to the attention of the Federal Reserve Banks and the Department of the Treasury, it does not purport to be exhaustive. Whenever a question arises whether or not an institution should, in accordance with the instructions on the TIC forms, be classified as official, the Federal Reserve Bank with which you file reports should be consulted. It should be noted that the list does not in every case include all alternative names applying to the same institution. -

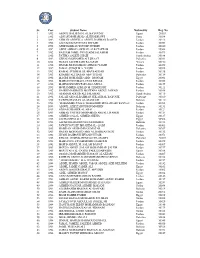

Sr. Year Student Name Nationality Reg. No. 1 1992 ABDUL HALEEM M

Sr. Year Student Name Nationality Reg. No. 1 1992 ABDUL HALEEM M. AL BAYOUMY Egypt 20053 2 1992 ADNAN MOHAMAD AL KHADRAWI Syria 30038 3 1992 AHMAD ABDULLA ABDUL RAHMAN DAOUD Jordan 30213 4 1992 ALI SALEM MUSTAFA DWAIRI Jordan 40051 5 1992 ATEF HABBAS YOUSEF HUSEIN Jordan 40040 6 1992 AWNI AHMAD AWWAD ALFATAFTAH Jordan 20064 7 1992 BASSAM JAMIL SWAILAIM SALAMEH Jordan 40073 8 1992 FATIMA SALEH GHAZI Saudi Arabia 30188 9 1992 GEHAD MOHAMED ALI SHAAT Palestine 30031 10 1992 HASAN SALEH SAID BAJAFAR Yemen 30150 11 1992 ISMAIL MOHAMMAD AHMAD YAGHI Jordan 40059 12 1992 JAMAL SUDQI M.A. YASIN Jordan 30028 13 1992 KAMAL SUBHI M. EL-HAJ BADDAR Jordan 30136 14 1992 KHAMIS ALI HASAN ABU TUHAH Palestine 30134 15 1992 MAGDI MOHAMED ABD - MONAM Egypt 20061 16 1992 MAHMOUD ISMAEL OUDI KHALIL Jordan 40028 17 1992 MAHMOUD MUSTAFA ESA MUSA Jordan 30157 18 1992 MOHAMMED AHMAD M. HAMSHARI Jordan 30111 19 1992 NAJEH MAHMOUD MOSTAFA ABDUL JAWAD Jordan 30058 20 1992 OSAMAH ADEEB ALI SALAMAH Saudi Arabia 30119 21 1992 SALAH ABD ALRAHMAN SHLASH AL BAYOUK Palestine 30010 22 1992 TAWFIQ HASSAN AL-MASKATI Bahrain 30110 23 1993 "MOHAMMED JUMA'A" MOHAMMED HUSSAIN ABU RAYYAN Jordan 40058 24 1993 ABDUL-AZIZ ZAINUDDIN MOHSIN Bahrain 30131 25 1993 ADNAN SHAHER AL'ARAJ Jordan 40121 26 1993 AHMAD YOUSEF MOHAMMD ABDALL HABEH Jordan 40124 27 1993 AHMED GALAL AHMED SHEHA Egypt 20137 28 1993 ALI HASHEM ALI Egypt 30306 29 1993 ALI MOHAMED HUSSN MOHAMED Bahrain 30183 30 1993 FAWZI YOUSEF IBRAHIM AL- QAISI Jordan 40003 31 1993 HAMDAN ALI HAMDAN MATAR Palestine 30267 32 1993 HASAN MOHAMED ABD AL RAHMAN BZEI Jordan 40132 33 1993 HUSNI BAHPOUH HUSAIN UTAIR Jordan 30071 34 1993 KHALIL GUMMA HEMDAN EL-MASRY Palestine 30007 35 1993 MAHMOUD ATYEH MOHD DAHBOUR Jordan 30079 36 1993 MOH'D ABDUL M. -

General Assembly

United Nations FOURTH COMMITTEE, 1571st GENERAL MEETING ASSEMBLY Monday, 29 November 1965, at 10.20 a.m. TJf/E,,'TIETH SESSIO;'' Official Records NEW YORK CONTENTS AGENDA ITEMS 69 AND 70 Page Question of South West Africa: reports of the Special Requests for hearings (continued) Com"nittee on the Situation with regard to the Requests concerning Oman (agenda item 73) lmiJiementation of the Declaration on the Granting (continued) . • . • . 331 of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples (continued) (A/5690 and Add.1-3; A/5781, A/5800/ Agenda items 69 and 70: Rev .1, chap. IV; A/5840, A/5949, A/5993, A/6000/ Question of South West Africa: reports of Rev.1, chap. IV: A/6035 and Add.1-4) the Special Committee on the Situation with regard to the Implementation of the Special educational and training programmes for Declaration on the Granting of Independence South West Africa: reports of the Secretary-General to Colonial Countries and Peoples (continued) (continued) (A/5782 and (orr .1, Add.l and Add.lj Special educational and training programmes Corr.l; A/6080 and Add.l and 2) for South West Africa: reports of the GEl"ERAL DEBATE (continued) Secretary-General (continued) General debate (continued). • 331 4. Mr. G. E. 0. \VILLIAMS (Sierra Leone) said that he would like to express his delegation's satisfaction Agenda item 73: at the announcement made at the previous meeting that Question of Oman: report of the Ad Hoc Com three South West African polit\cal parties would unite mittee on Oman to further their cause. General debate. -

University of London Oman and the West

University of London Oman and the West: State Formation in Oman since 1920 A thesis submitted to the London School of Economics and Political Science in candidacy for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Francis Carey Owtram 1999 UMI Number: U126805 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U126805 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 bLOSiL ZZLL d ABSTRACT This thesis analyses the external and internal influences on the process of state formation in Oman since 1920 and places this process in comparative perspective with the other states of the Gulf Cooperation Council. It considers the extent to which the concepts of informal empire and collaboration are useful in analysing the relationship between Oman, Britain and the United States. The theoretical framework is the historical materialist paradigm of International Relations. State formation in Oman since 1920 is examined in a historical narrative structured by three themes: (1) the international context of Western involvement, (2) the development of Western strategic interests in Oman and (3) their economic, social and political impact on Oman. -

UK Armed Forces Operational Deaths Post World War II

UK armed forces Deaths: Operational deaths post World War II 3 September 1945 to 28 February 2021 Published 25 March 2021 This Official Statistic provides summary information on the number of in-service deaths among UK armed forces personnel which occurred as a result of a British, United Nations (UN) or North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) medal earning operation since World War II. This report is updated annually at the end of March and six weeks after the end of each medal earning operation. Key points and trends Since the end of World War II, 7,190 UK armed forces personnel have died as a result of operations in medal earning theatres. There have been no operational deaths since the previous publication. The largest number of deaths among UK armed forces personnel in one operation was the loss of 1,442 lives in Malaya. NATO or United Nations led operations in Cyprus, the Balkans, Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria are ongoing. As at 28 February 2021: - Four UK armed forces personnel have died as a result of operations in Cyprus (UNFICYP). - 72 UK armed forces personnel have died as a result of operations in the Balkans. - 457 UK armed forces personnel have died as a result of operations in Afghanistan. - Four UK armed forces personnel have died as a result of Operation SHADER. Three deaths occurred in Iraq and one in Cyprus. Responsible statistician: Deputy Head of Defence Statistics Health Tel. 030 679 84411 [email protected] Further information/mailing list: [email protected] Background quality report: The Background Quality Report for this publication can be found here at www.gov.uk Enquiries: Press Office: 020 721 83253 Would you like to be added to our contact list, so that we can inform you about updates to these statistics and consult you if we are thinking of making changes? You can subscribe to updates by emailing [email protected] 1 Contents Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………………………….. -

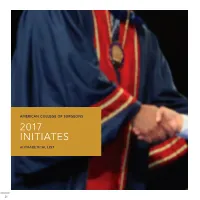

2017 Initiates Alphabetical List

AMERICAN COLLEGE OF SURGEONS 2017 INITIATES ALPHABETICAL LIST 30 Hanser Antonio Abreu Quezada Khaled Sami Ahmad Ali Alaraj A Santiago, Dominican Republic Riyadh, Saudi Arabia Chicago, IL Amaar Awad Hussien Hussien Carlos Maria Abril Vega Siddique Ahmad Yakout Hameed Alaraji Aamery Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates Peshawar, Pakistan Dubai, United Arab Emirates Wolverhampton, United Kingdom Walid Abu Tahoun Usman Ahmad Nasrin Alavi Wesley M. Abadie Dhahran, Saudi Arabia Cleveland, OH Tehran, Iran, Islamic Republic of Williamsburg, VA Abdelrahman Hassan Abusabeib Azam S. Ahmed Marco Alfonso Albán Garcia Andrea M. Abbott Doha, Qatar Madison, WI Santiago, Chile Mount Pleasant, SC Jihad Achkar Tanveer Ahmed Hamdullah Hadi Al-Baseesee Abdel Rahman Abdel Fattah M. Beirut, Lebanon Dhaka, Bangladesh Najaf, Iraq Abdel Aal Doha, Qatar Alison Alden Acott Manish Ahuja Michael A. Albin Little Rock, AR Mumbai, India South Pasadena, CA Karim Sabry Abdel Samee Cairo, Egypt Badih Adada Naveen Kumar Ahuja Saleh Mohammad Aldaqal Weston, FL Hamilton, NJ Jeddah, Saudi Arabia Eltayib Yousif Abdelaleem Doha, Qatar Patrick Temi Adegun Begum Akay Saad A. A. A. Aldousari Ado-Ekiti, Nigeria Birmingham, MI Kuwait City, Kuwait Tamer Mohamed Said Abdelbaki Salama James Olaniyi Adeniran Hakkı Tankut Akay Matthew J. Alef Cairo, Egypt Ilorin, Kwara State, Nigeria Ankara, Turkey Winooski, VT Kareem R. AbdelFattah Adedoyin Adekunle Adesanya Raed Hatmal Akayleh Farzad Alemi Dallas, TX Lagos, Nigeria Amman, Jordan Kansas City, MO Khaled Mohamed Saad Obinna Ogochukwu Adibe Ahmet Akman Naif Abdullah Alenazi Mostafa Abdelgalel Chapel Hill, NC Ankara, Turkey Riyadh, Saudi Arabia Ajman, United Arab Emirates Farrell C. Adkins Mohamed Gomah Hamed Falih Mohssen Algazgooz Ahmed Mohamed Abdelkader Roanoke, VA Al Aqqad Basra, Iraq Dubai, United Arab Emirates Dubai, United Arab Emirates John Affuso Mohammed S. -

Britain in Iraq: Contriving King and Country'

H-Albion Satia on Sluglett, 'Britain in Iraq: Contriving King and Country' Review published on Friday, February 1, 2008 Peter Sluglett. Britain in Iraq: Contriving King and Country. New York: Columbia University Press, 2007. 318 pp. $24.50 (paper), ISBN 978-0-231-14201-4. Reviewed by Priya Satia (Department of History, Stanford University)Published on H-Albion (February, 2008) Lessons in Imperialism from Iraq's Past The current war in Iraq has had many ironic consequences, the least sordid being perhaps the belated interest in Iraq's history. As Peter Sluglett confesses in the opening pages of the reissue of his thirty-year-old classic, Britain in Iraq, his happiness about the book's new lease of life is severely undercut by his awareness of its unhappy cause. (One at once anticipates and dreads a similar resurrection of long-neglected works on Iranian history in the near future.) While the continued obscurity of important historical texts underscores the ignorance guiding the prosecution of American war and diplomacy in the Middle East, the irony lies as much in the pedagogue's self- defeatist awareness that if only such books had been read in the halls of power earlier, they would have remained neatly irrelevant to our wider political life. That said, the timely reissue of Sluglett's book is an opportunity to comment on scholarship as much as politics, and that is, happily, a notably less pathetic story. Sluglett's original 1976 edition has long been the definitive text on the period of the British mandate in Iraq, from World War I to 1932. -

Oman's Foreign Policy : Foundations and Practice

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 11-7-2005 Oman's foreign policy : foundations and practice Majid Al-Khalili Florida International University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Al-Khalili, Majid, "Oman's foreign policy : foundations and practice" (2005). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1045. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/1045 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida OMAN'S FOREIGN POLICY: FOUNDATIONS AND PRACTICE A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS by Majid Al-Khalili 2005 To: Interim Dean Mark Szuchman College of Arts and Sciences This dissertation, written by Majid Al-Khalili, and entitled Oman's Foreign Policy: Foundations and Practice, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this dissertation and recommend that it be approved. Dr. Nicholas Onuf Dr. Charles MacDonald Dr. Richard Olson Dr. 1Mohiaddin Mesbahi, Major Professor Date of Defense: November 7, 2005 The dissertation of Majid Al-Khalili is approved. Interim Dean Mark Szuchman C lege of Arts and Scenps Dean ouglas Wartzok University Graduate School Florida International University, 2005 ii @ Copyright 2005 by Majid Al-Khalili All rights reserved.