Whitney M. Young, Jr., Oral History Interview I, 6/18/69, by Thomas Harrison Baker, Internet Copy, LBJ Library

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cuba Family Archives for Southern Jewish History at the Breman Museum

William Breman Jewish Heritage Museum Cuba Family Archives for Southern Jewish History Weinberg Center for Holocaust Education THE CUBA FAMILY ARCHIVES FOR SOUTHERN JEWISH HISTORY AT THE BREMAN MUSEUM MSS 250, CECIL ALEXANDER PAPERS BOX 1, FILE 10 BIOGRAPHY, 2000 THIS PROJECT WAS MADE POSSIBLE BY THE GENEROUS SUPPORT OF THE ALEXANDER FAMILY ANY REPRODUCTION OF THIS MATERIAL WITHOUT THE EXPRESSED WRITTEN CONSENT OF THE CUBA FAMILY ARCHIVES IS STRICTLY PROHIBITED The William Breman Jewish Heritage Museum ● 1440 Spring Street NW, Atlanta, GA 30309 ● (678) 222-3700 ● thebreman.org CubaFamily Archives Mss 250, Cecil Alexander Papers, The Cuba Family Archives for Southern Jewish History at The Breman Museum. THE AMERICAN INSTITUTE OF ARCIDTECTS October 2, 2000 Ben R. Danner, FAIA Director, Sowh Atlantic Region Mr. Stephen Castellanos, FAIA Whitney M. Young, Jr. Award C/o AlA Honors and Awards Department I 735 New York Avenue, NW Washington, D.C. 20006-5292 Dear Mr. Castellanos: It is my distinct privilege to nominate Cecil A. Alexander, FAIA for the Whitney M. Young, Jr. Award. Mr. Alexander is a man whose life exemplifies the meaning of the award. He is a distinguished architect who has led the effort to foster better understanding among groups and promote better race relations in Atlanta. Cecil was a co-founder, with Whitney Young, of Resurgens Atlanta, a group of civic and business leaders dedicated to improving race relations that has set an example for the rest of the nation. Cecil was actively involved with social issues long before Mr. Young challenged the AlA to assume its professional responsibility toward these issues. -

A Tale of Prosecutorial Indiscretion: Ramsey Clark and the Selective Non-Prosecution of Stokley Carmichael

South Carolina Law Review Volume 62 Issue 1 Article 2 Fall 2010 A Tale of Prosecutorial Indiscretion: Ramsey Clark and the Selective Non-Prosecution of Stokley Carmichael Lonnie T. Brown Jr. University of Georgia School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/sclr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Lonnie T. Brown, Jr., A Tale of Prosecutorial Indiscretion: Ramsey Clark and the Selective Non-Prosecution of Stokley Carmichael, 62 S. C. L. Rev. 1 (2010). This Article is brought to you by the Law Reviews and Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in South Carolina Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Brown: A Tale of Prosecutorial Indiscretion: Ramsey Clark and the Select A TALE OF PROSECUTORIAL INDISCRETION: RAMSEY CLARK AND THE SELECTIVE NON-PROSECUTION OF STOKELY CARMICHAEL LONNIE T. BROWN, JR.* I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 1 II. THE PROTAGONISTS .................................................................................... 8 A. Ramsey Clark and His Civil Rights Pedigree ...................................... 8 B. Stokely Carmichael: "Hell no, we won't go!.................................. 11 III. RAMSEY CLARK'S REFUSAL TO PROSECUTE STOKELY CARMICHAEL ......... 18 A. Impetus Behind Callsfor Prosecution............................................... 18 B. Conspiracy to Incite a Riot.............................................................. -

The Powerbroker: Whitney Young’S Fight for Civil Rights

DISCUSSION GUIDE The Powerbroker: Whitney Young’s Fight for Civil Rights PBS.ORG/indePendenTLens/POWERBROKER Table of Contents 1 Using this Guide 2 From the Filmmaker 3 The Film 4 Background Information 5 Biographical Information on Whitney Young 6 The Leaders and Their Organizations 8 From Nonviolence to Black Power 9 How Far Have We Come? 10 Topics and Issues Relevant to The Powerbroker: Whitney Young’s Fight for Civil Rights 10 Thinking More Deeply 11 Suggestions for Action 12 Resources 13 Credits national center for MEDIA ENGAGEMENT Using this Guide Community Cinema is a rare public forum: a space for people to gather who are connected by a love of stories, and a belief in their power to change the world. This discussion guide is designed as a tool to facilitate dialogue, and deepen understanding of the complex issues in the film The Powerbroker: Whitney Young’s Fight for Civil Rights. It is also an invitation to not only sit back and enjoy the show — but to step up and take action. This guide is not meant to be a comprehensive primer on a given topic. Rather, it provides important context, and raises thought provoking questions to encourage viewers to think more deeply. We provide suggestions for areas to explore in panel discussions, in the classroom, in communities, and online. We also provide valuable resources, and connections to organizations on the ground that are fighting to make a difference. For information about the program, visit www.communitycinema.org DISCUSSION GUIDE // THE POWERBROKER 1 From the Filmmaker I wanted to make The Powerbroker: Whitney Young’s Fight for Civil Rights because I felt my uncle, Whitney Young, was an important figure in American history, whose ideas were relevant to his generation, but whose pivotal role was largely misunderstood and forgotten. -

Black-Jewish Coalition” Unraveled: Where Does Israel Fit?

The “Black-Jewish Coalition” Unraveled: Where Does Israel Fit? A Master’s Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Hornstein Jewish Professional Leadership Program Professors Ellen Smith and Jonathan Krasner Ph.D., Advisors In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Leah Robbins May 2020 Copyright by Leah Robbins 2020 Acknowledgements This thesis was made possible by the generous and thoughtful guidance of my two advisors, Professors Ellen Smith and Jonathan Krasner. Their content expertise, ongoing encouragement, and loving pushback were invaluable to the work. This research topic is complex for the Jewish community and often wrought with pain. My advisors never once questioned my intentions, my integrity as a researcher, or my clear and undeniable commitment to the Jewish people of the past, present, and future. I do not take for granted this gift of trust, which bolstered the work I’m so proud to share. I am also grateful to the entire Hornstein community for making room for me to show up in my fullness, and for saying “yes” to authentically wrestle with my ideas along the way. It’s been a great privilege to stretch and grow alongside you, and I look forward to continuing to shape one another in the years to come. iii ABSTRACT The “Black-Jewish Coalition” Unraveled: Where Does Israel Fit? A thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Brandeis University Waltham, Massachusetts By Leah Robbins Fascination with the famed “Black-Jewish coalition” in the United States, whether real or imaginary, is hardly a new phenomenon of academic interest. -

Women in the Modern Civil Rights Movement

Women in the Modern Civil Rights Movement Introduction Research Questions Who comes to mind when considering the Modern Civil Rights Movement (MCRM) during 1954 - 1965? Is it one of the big three personalities: Martin Luther to Consider King Jr., Malcolm X, or Rosa Parks? Or perhaps it is John Lewis, Stokely Who were some of the women Carmichael, James Baldwin, Thurgood Marshall, Ralph Abernathy, or Medgar leaders of the Modern Civil Evers. What about the names of Septima Poinsette Clark, Ella Baker, Diane Rights Movement in your local town, city or state? Nash, Daisy Bates, Fannie Lou Hamer, Ruby Bridges, or Claudette Colvin? What makes the two groups different? Why might the first group be more familiar than What were the expected gender the latter? A brief look at one of the most visible events during the MCRM, the roles in 1950s - 1960s America? March on Washington, can help shed light on this question. Did these roles vary in different racial and ethnic communities? How would these gender roles On August 28, 1963, over 250,000 men, women, and children of various classes, effect the MCRM? ethnicities, backgrounds, and religions beliefs journeyed to Washington D.C. to march for civil rights. The goals of the March included a push for a Who were the "Big Six" of the comprehensive civil rights bill, ending segregation in public schools, protecting MCRM? What were their voting rights, and protecting employment discrimination. The March produced one individual views toward women of the most iconic speeches of the MCRM, Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a in the movement? Dream" speech, and helped paved the way for the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and How were the ideas of gender the Voting Rights Act of 1965. -

Jazz at Congo Square Festival

Lighting The Road To The Future Data Zone Transformation! Page 4 “The People’s Paper” August 7 - August 13, 2021 56th Year Volume 15 www.ladatanews.com A Data News Weekly Exclusive Sunni Patterson The Stooges Brass Band Delfeayo Marsalis Presents: The First Annual Kyle Roussell Jazz at Vegas Cola Band Congo Downtown Leslie Brown Square Luther Gray Festival Tonya Boyd-Cannon Page 2 Mykia Jovan Newsmaker State & Local John Bel Edwards City to Host Community- Temporarily Reinstates Based Rental Indoor Mask Mandate Assistance Event Page 6 Page 7 Page 2 August 7 - August 13, 2021 Cover Story www.ladatanews.com Delfeayo Marsalis Presents: The First Annual Jazz at Congo Square Festival Delfeayo Marsalis and the Uptown Jazz Orchestra. Photos by Zac Smith Edwin Buggage Editor-in-Chief Celebrating and Honoring A Rich Cultural Heritage New Orleans continues to be a City rich and amazing in its heri- tage; one where people from across the globe keep coming to ex- perience its awe. In its over three centuries, it has given the world many gifts in food, music, culture, and a way of life that merges Af- rica, Europe, the Caribbean and South America into a rich gumbo. It is the drumbeat of Bamboula, that began at Congo Square, and continues to be the heartbeat of the City. On August 8, 2021, from 1-7 p.m. at Congo Square, Delf- eayo Marsalis and the Uptown Jazz Orchestra will host the Delfeayo Marsalis and his father, the late great educator, musician and bandleader Cover Story, Continued on page 3. Ellis Marsalis. -

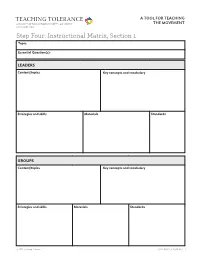

Step Four: Instructional Matrix, Section 1 Topic

TEACHING TOLERANCE A TOOL FOR TEACHING A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER THE MOVEMENT TOLERANCE.ORG Step Four: Instructional Matrix, Section 1 Topic: Essential Question(s): LEADERS Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Strategies and skills Materials Standards GROUPS Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Strategies and skills Materials Standards © 2014 Teaching Tolerance CIVIL RIGHTS DONE RIGHT TEACHING TOLERANCE A TOOL FOR TEACHING A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER THE MOVEMENT TOLERANCE.ORG STEP FOUR: INSTRUCTIONAL MATRIX, SECTION 1 (CONTINUED) Topic: EVENTS Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Strategies and skills Materials Standards HISTORICAL CONTEXT Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Strategies and skills Materials Standards © 2014 Teaching Tolerance CIVIL RIGHTS DONE RIGHT TEACHING TOLERANCE A TOOL FOR TEACHING A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER THE MOVEMENT TOLERANCE.ORG STEP FOUR: INSTRUCTIONAL MATRIX, SECTION 1 (CONTINUED) Topic: OPPOSITION Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Strategies and skills Materials Standards TACTICS Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Strategies and skills Materials Standards © 2014 Teaching Tolerance CIVIL RIGHTS DONE RIGHT TEACHING TOLERANCE A TOOL FOR TEACHING A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER THE MOVEMENT TOLERANCE.ORG STEP FOUR: INSTRUCTIONAL MATRIX, SECTION 1 (CONTINUED) Topic: CONNECTIONS Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Strategies and skills Materials Standards © 2014 Teaching Tolerance CIVIL RIGHTS DONE RIGHT TEACHING TOLERANCE A TOOL FOR TEACHING A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER THE MOVEMENT TOLERANCE.ORG Step Four: Instructional Matrix, Section 1 (SAMPLE) Topic: 1963 March on Washington Essential Question(s): How do the events and speeches of the 1963 March on Washington illustrate the characteristics of the civil rights movement as a whole? LEADERS Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Martin Luther King Jr., A. -

Women in the Movement

WOMEN IN THE MOVEMENT ESSENTIAL QUESTION ACTIVITIES How did women leaders influence the civil rights movement? 2 Do-Now: Opening Questions LESSON OVERVIEW 2 A Close View: In this lesson students will expand their historical understanding and appreciation Analyzing Images of women in the Civil Rights Movement, especially the role of Coretta Scott King as 3 Analyzing Film as Text a woman, mother, activist, and wife. Students also will learn about other women leaders in the movement through listening and analyzing first-person interviews 4 Close View of Interview from The Interview Archive. Threads Students will apply the historical reading skills of sourcing, contextualization, 5 Research: Corroboration and corroboration, and broaden their skills and use of close reading strategies by analyzing historical images, documentary film, and first-person interviews alongside 5 Closing Discussion Questions the transcript. As a demonstration of learning and/or assessment, students will 6 Homework or Extended write a persuasive essay expanding on their understanding of women in the Civil Learning Rights Movement through a writing prompt. Through this process students will continue to build upon the essential habits of a historian and establish a foundation for critical media literacy. HANDOUTS LESSON OBJECTIVES 7 Close View of the Film Students will use skills in reading history and increase their understanding of history, particularly of women in the Civil Rights Movement, by: 8 Women in the Movement: • Analyzing primary source materials including photographs and documents Interview Thread One • Critically viewing documentary film and first-person interviews to inform 10 Women in the Movement: their understanding of the lesson topic Interview Thread Two • Synthesizing new learning through developing questions for further historical inquiry • Demonstrating their understanding of the lesson topic through a final writing exercise MATERIALS • Equipment to project photographs • Equipment to watch video • Copies of handouts 1 ACTIVITIES 1. -

Nixon Leads Mourners at Young Funeral

Nixon Leads Mourners at Young Funeral 13y THOMAS A. JOHNSON that officials of the adjacent, LEXINGTON, Ky., March 17 racially mixed Lexington Ceme- — President Nixon said today tery had offered a more expan- that "A great nation will pay sive burial plot but, that the its respects to Whitney Young family had chosen to have Mr. by continuing the work to which Young buried in the black-ceme- he dedicated his entire fife." tery in lots that had been Standing in a small Negro owned for many years by his cemetery beside the flower- parents. It was said that Mr. decked coffin of Mr. Young, Young's deceased mother had who was the executive direc- requested that he be buried tor of the National Urban near her grave. League, the President eulo- The area in which Mr. Young gized the civil rights 'leader "as was buried had fallen into dis- a very complex man" who will repair in recent years, and Gov. be remembered as a doer, not Louis Nunn ordered it cleaned 'a talker." up last week. It was overgrown Wearing a gray suit without with weeds and abandoned a topcoat, despite the chilly cars, and refuse had been overcast day, Mr. Nixon stood spread over the plots. erect and spoke without the State crews also cut back the benefit of notes. In solemn, sagging limbs of several ceme- measured tones, he said that tery oak trees that today Mr. Young's genius was that showed the fresh, white scars "he knew how to accomplish against the rough, black bark what other people were merely of the tree trunks. -

Martin Luther King Jr January 2021

Connections Martin Luther King Jr January 2021 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR PMB Administrative Services and the Office of Diversity, Inclusion and Civil Rights Message from the Deputy Assistant Secretary for Administrative Services January 2021 Dear Colleagues, The life and legacy of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., inspires me every day, particularly when the troubles of the world seem to have placed what appear to be insurmountable obstacles on the path to achieving Dr. King’s vision. Yet I know that those obstacles will eventually melt away when we focus our hearts and minds on finding solutions together. While serving as leaders of the civil rights movement, Dr. and Mrs. King raised their family in much the same way my dear parents raised my brothers and myself. It gives me comfort to know that at the end of the day, their family came together in love and faith the same way our family did, grateful for each other and grateful knowing the path ahead was illuminated by a shared dream of a fair and equitable world. This issue of Connections begins on the next page with wise words of introduction from our collaborative partner, Erica White-Dunston, Director of the Office of Diversity, Inclusion and Civil Rights. Erica speaks eloquently of Dr. King’s championing of equity, diversity and inclusion in all aspects of life long before others understood how critically important those concepts were in creating and sustaining positive outcomes. I hope you find as much inspiration and hope within the pages of this month’s Connections magazine as I did. -

President's Daily Diary, July 27, 1967

fem House Date July 27, 1967 « NT LYNDON B. JOHNSON WA*Y Th e Whit e House Thursday 'resident began his day at (Place)___ Day Time Telephone 1 1 Activity (include visited by) la Out Lo LD 3:28a £ The Situation Room * 7:53a f Hon. Cyrus Vance - Detroit, Michigan 8:54a tf "4^ Justice Abe Fortas - Westport , Connecticu t 9:09a f Walt Rostow ' 9:31a t Secretary Fowler 9:44a t_ Harr y McPherson - pl 10:05a £ Douglass Cater - pl 10:20a £ Hon. Ramsey Clark - the Attorney General ^" • | 10:30a t j Hon . Ramsey Clark - the Attorney General- I | 10:35a t | Joseph Califano 10:45a f I "~ MW •^— .. -^-^—— 10:47a t M W - pl 11:05aJ} . f 1 Joe Califano 'HUE HOUSE Date Jul y 27, 1967 ENT LYNDON B. JOHNSON MARY The White 'resident began his day at (Place) House Day Thursda y Tune Telephone j Activity (include visited by) In Out Lo LD 11:14a t Secy McNamara / 11:19a t Gov. Farris Bryant 11:25a t Joe Califan o - pl \ /_• ^ZjZZ_ _ : 11:32a t General Andrew Goodpaster / : 11:41a t Hon. Ramsey Clark - the Attorney General 12:15p t Secy McNamara 12:25p t Joe Califano - pl 12:26p t Tom Johnson - pl /: 12:43p f The Attorney General - Hon. Ramsey Clark 12:55p j To the Oval Ofc I 7~~12:56p 1:00p| i Presentation D of Credentials - Fish Room CS H. E. Dr. Alexandre Ohin, Ambassador of the Republic of Togo ^ H. E. Corneliu Bogdan, Ambassador of the Socialist Republic of Romania VHITE Hoosf n a,. -

Whitney M. YOUNG Scholars Program®, Is Cre- Ated to Serve the Educational Needs of Academically Tal- Ented, Economically Disadvantaged Middle/High School Students

Lincoln Foundation Historical Timeline 1904 - Passage of the Day Law halts interracial education at Berea College in Berea, Kentucky. Scholar Oath 1908 - Day Law is ruled constitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court. “I can, 1909 - Berea College Board of Trustees purchases 444.4 I must acres in Lincoln Ridge, KY, the site of Lincoln Institute. I will be somebody. Whitney M. YOUNG 1910 - Lincoln Institute becomes a legal entity and the Lincoln Institute of Kentucky Board of Trustees is estab- For all that I do, Scholars Program® lished to oversee and manage its assets. Spirit tried and true, 1911 - Cornerstone for Berea Hall is laid in October. Only the best of me 1912 - The Lincoln Institute is dedicated and 85 black stu- Will come shining through dents enroll on October 1. Not my mother 1928 - The junior college is Not my father closed in order to focus on the core mission of being an Nor my enemies who try to stray me, elite boarding high school for But by my own undying heart, blacks. Berea Hall, Lincoln Institute 1947 - Lincoln Institute becomes Which beats on ever steady. a public school. Lincoln Institute of Kentucky is renamed It is with this pledge, the Lincoln Foundation. I set my life, 1949 - Whitney Young, Sr. is named the first black presi- dent of the Institute after having served as principal since And with it vow to be, 1935. A winner first, 1950 - Kentucky General Assembly repeals the Day Law. A winner last Kentucky slowly begins the process of integrating schools. 1954 - The U.S.