Amici Brief File Stamped 020718(Pdf)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Middle East Oil Pricing Systems in Flux Introduction

May 2021: ISSUE 128 MIDDLE EAST OIL PRICING SYSTEMS IN FLUX INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................................................ 2 THE GULF/ASIA BENCHMARKS: SETTING THE SCENE...................................................................................................... 5 Adi Imsirovic THE SHIFT IN CRUDE AND PRODUCT FLOWS ..................................................................................................................... 8 Reid l'Anson and Kevin Wright THE DUBAI BENCHMARK: EVOLUTION AND RESILIENCE ............................................................................................... 12 Dave Ernsberger MIDDLE EAST AND ASIA OIL PRICING—BENCHMARKS AND TRADING OPPORTUNITIES......................................... 15 Paul Young THE PROSPECTS OF MURBAN AS A BENCHMARK .......................................................................................................... 18 Michael Wittner IFAD: A LURCHING START IN A SANDY ROAD .................................................................................................................. 22 Jorge Montepeque THE SECOND SPLIT: BASRAH MEDIUM AND THE CHALLENGE OF IRAQI CRUDE QUALITY...................................... 29 Ahmed Mehdi CHINA’S SHANGHAI INE CRUDE FUTURES: HAPPY ACCIDENT VERSUS OVERDESIGN ............................................. 33 Tom Reed FUJAIRAH’S RISE TO PROMINENCE .................................................................................................................................. -

Global Energy 2012 Conference & Exhibition

GLOBAL 12 ENERGY 20 29/30/31 OCTOBER 2012 HOTEL PRESIDENT WILSON Global Energy Geneva 2012 Where the oil & gas trade meets...with key participation of Cargill, Gunvor, Lundin, Lukoil, Mercuria, Socar, Trafigura To register: www.globalenergygeneva.com GLOBAL 12 ENERGY 20 GLOBAL ENERGY 2012 CONFERENCE & EXHIBITION 29/30/31 October 2012, Hotel President Wilson, Geneva T: +41 (0) 22 321 74 80 | F: +41 (0) 22 321 74 82 | E: [email protected] | www.globalenergygeneva.com About Global Energy 2012 The oil and gas trade is critical to the global economy and the effect of energy prices and trade is more profound than for any other traded commodity. Global Energy is a trade show, conference and exhibition unique to Geneva. Global Energy 2012 is being held on October 29/30/31 at the prestigious Hotel President Wilson in the heart of Geneva. The event brings together energy traders, banks, policymakers, delivering important keynote speeches and panel debates. Global Energy 2012 takes place during an important week in the Geneva commodities trade calendar. It will be attended by a “who’s who” in oil and gas in Switzerland and abroad. Who will attend Global Energy 2012? Major international oil & gas trading firms Traders from small and medium-sized firms throughout the globe Leaders in the Swiss energy trade community Upstream oil and gas majors – interested in the global S&D of oil and gas Oil and gas investors, including family offices and private banks Trade financiers specialising in oil and gas Professional firms: lawyers, advisory/management -

Redstone Commodity Update Q3

Welcome to the Redstone Commodity Update 2020: Q3 Welcome to the Redstone Commodity Moves Update Q3 2020, another quarter in a year that has been strongly defined by the pandemic. Overall recruitment levels across the board are still down, although we have seen some pockets of hiring intent. There appears to be a general acknowledgement across all market segments that growth must still be encouraged and planned for, this has taken the form in some quite senior / structural moves. The types of hires witnessed tend to pre-empt more mid-junior levels hires within the same companies in following quarters, which leaves us predicting a stronger than expected finish to Q4 2020 and start to Q1 2021 than we had previously planned for coming out of Q2. The highest volume of moves tracked fell to the energy markets, notably, within power and gas and not within the traditional oil focused roles, overall, we are starting to see greater progress towards carbon neutrality targets. Banks such as ABN, BNP and SocGen have all reduced / pulled out providing commodity trade finance, we can expect competition for the acquiring of finance lines to heat up in the coming months until either new lenders step into the market or more traditional lenders swallow up much of the market. We must also be aware of the potential impact of the US elections on global trade as countries such as Great Britain and China (amongst others) await the outcome of the impending election. Many national trade strategies and corporate investment strategies will hinge on this result in a way that no previous election has. -

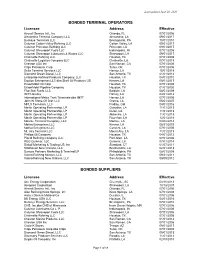

Bonded Terminal Operators

Last updated June 26, 2020 BONDED TERMINAL OPERATORS Licensee Address Effective Aircraft Service Intl., Inc Orlando, FL 07/01/2006 Alexandria Terminal Company LLC Alexandria, LA 09/01/2017 Buckeye Terminals LLC Breinigsville, PA 10/01/2010 Calumet Cotton Valley Refining LLC Cotton Valley, LA 09/01/2017 Calumet Princeton Refining LLC Princeton, LA 09/01/2017 Calumet Shreveport Fuels LLC Indianapolis, IN 07/01/2006 Calumet Shreveport Lubricants & Waxes LLC Shreveport, LA 09/01/2017 Chalmette Refining LLC Houston, TX 07/01/2006 Chalmette Logistics Company LLC Chalmette, LA 07/01/2018 Chevron USA Inc San Ramon, CA 07/01/2006 Citgo Petroleum Corp Tulsa, OK 07/01/2006 Delta Terminal Services LLC Harvey, LA 10/01/2018 Diamond Green Diesel, LLC San Antonio, TX 01/01/2014 Enterprise Refined Products Company, LLC Houston, TX 04/01/2010 Equilon Enterprises LLC dba Shell Oil Products US Kenner, LA 05/01/2017 ExxonMobil Oil Corp Houston, TX 07/01/2006 ExxonMobil Pipeline Company Houston, TX 01/01/2020 Five Star Fuels, LLC Baldwin, LA 08/01/2009 IMTT-Gretna Harvey, LA 04/01/2012 International-Matex Tank Terminals dba IMTT Harvey, LA 07/01/2006 John W Stone Oil Dist, LLC Gretna, LA 05/01/2007 MPLX Terminals, LLC Findlay, OH 04/01/2016 Martin Operating Partnership, LP Gueydan, LA 11/01/2013 Martin Operating Partnership, LP Dulac, LA 11/01/2013 Martin Operating Partnership, LP Abbeville, LA 11/01/2013 Martin Operating Partnership, LP Fourchon, LA 12/01/2016 Monroe Terminal Company, LLC Monroe, LA 04/08/2014 Motiva Enterprises LLC Kenner, LA 08/21/2009 Motiva Enterprises LLC Convent, LA 07/01/2006 Mt. -

Financing Options in the Oil and Gas Industry, Practical Law UK Practice Note

Financing options in the oil and gas industry, Practical Law UK Practice Note... Financing options in the oil and gas industry by Suzanne Szczetnikowicz and John Dewar, Milbank, Tweed, Hadley & McCloy LLP and Practical Law Finance. Practice notes | Maintained | United Kingdom Scope of this note Industry overview Upstream What is an upstream oil and gas project? Typical equity structure Relationship with the state Key commercial contracts in an upstream project Specific risks in financing an upstream project Sources of financing in the upstream sector Midstream, downstream and integrated projects Typical equity structures What is a midstream oil and gas project? Specific risks in financing a midstream project What is a downstream oil and gas project? Specific risks in financing a downstream project Integrated projects Sources of financing in midstream, downstream and integrated projects Multi-sourced project finance Shareholder funding Equity bridge financing Additional sources of financing Other financing considerations for the oil and gas sectors Expansion financings Hedging Refinancing Current market trends A note on the structures and financing options and risks typically associated with the oil and gas industry. © 2018 Thomson Reuters. All rights reserved. 1 Financing options in the oil and gas industry, Practical Law UK Practice Note... Scope of this note This note considers the structures, financing options and risks typically associated with the oil and gas industry. It is written from the perspective of a lawyer seeking to structure a project that is capable of being financed and also addresses the aspects of funding various components of the industry from exploration and extraction to refining, processing, storage and transportation. -

Commodities Price Volatity in the 2000S Unpacking Financialisation Samuel K

Commodities Price Volatity in the 2000s Unpacking financialisation Samuel K. GAYI Special Unit on Commodities UNCTAD 0utline • Context – Price trends, 1960-2011 • New twists • Financialization – What is it? – Some concerns – Evidence – UNCTAD vs others • Refocus on fundamentals • Concluding remarks Context Overview of Price trends 1960-2011 Fig. 1: Non oil commodity price index in constant terms, 1960-2011 (2000 = 100) Fig. 2: Historical commodity real price indices, 1960-2011 600 500 400 300 Real price index, 2000=100 index, price Real 200 100 - 1960 1963 1966 1969 1972 1975 1978 1981 1984 1987 1990 1993 1996 1999 2002 2005 20082011e Food Tropical beverages Agricultural Raw Materials Minerals, Ores and Metals Crude petroleum Overview of price trends, 1960-2011 • Since 1960: real prices of non-fuel commodities relatively stable (highest peak in 1974 - oil shock); • 1980-2000: commodity prices volatile, but generally declined with temporary peaks in 1988 and 1997. • 1997—1999: Asian crisis contributed to slump in US $ prices for primary commodities of 20% (compared to 5% for manufactures) (Page & Hewitt, 2001); • By mid-2008, commodities had enjoyed 5-year price boom - longest & broadest rally of the post-World War II period, i.e., after almost 30 years of generally low but moderately fluctuating prices. • Relatively well established that there is a long-term downward decline in the relative prices of primary commodities vis-à-vis manufactures (Maizels, 1992). Overview of price trends (ii) • Since 1960, two major commodity price booms (1973-1980, & 2003- 2011); • Current (recent?) commodity price boom is different from 1970s boom. Note:1970s commodity price spikes were short- lived (Radetzki 2006; Kaplinsky and Farooki, 2009); • Historical data: significantly higher real prices for beverages and food commodities were recorded in the 1970s, relative to 2003 to 2011; • However, rise in commodity prices 2003-11, especially from 2006 to 2008, is particularly pronounced in the case of metals, crude oil and food (Fig. -

Swiss Extractivism: Switzerland's Role in Zambia's Copper Sector*

J. of Modern African Studies, , (), pp. – © Cambridge University Press . This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/./), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. doi:./SX Swiss extractivism: Switzerland’s role in Zambia’s copper sector* GREGOR DOBLER University of Freiburg, Institut für Ethnologie, Werthmannstr. , Freiburg, Germany Email: [email protected] and RITA KESSELRING University of Basel, Ethnologisches Seminar, Münsterplatz , Basel, Switzerland Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Switzerland is usually not looked upon as a substantial economic actor in Africa. Taking Zambian copper as a case study, we show how important Swiss companies have become in the global commodities trade and the services it depends on. While big Swiss trading firms such as Glencore and Trafigura have generated increasing scholarly and public interest, a multitude of Swiss companies is involved in logistics and transport of Zambian copper. Swiss extractivism, we argue, is a model case for trends in today’s global capitalism. We highlight that servicification, a crucial element of African mining regimes today, creates new and more flexible opportun- ities for international companies to capture value in global production networks. These opportunities partly rely on business-friendly regulation and tax regimes in Northern countries, a fact which makes companies potentially vulnerable to * Research for this article has been funded by SNIS, the Swiss Network for International Studies. We are grateful to all project partners in the Valueworks project. We finished the article as Fung Global Fellow at the Institute for International and Regional Studies (PIIRS), Princeton University (Rita Kesselring), and as Visitor at the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton (Gregor Dobler); we are very grateful to both institutions for the inspiring writing environment they offered. -

The Endgame for Commodity Traders Why Only the Biggest and Digitally Advanced Traders Will Thrive

THE ENDGAME FOR COMMODITY TRADERS WHY ONLY THE BIGGEST AND DIGITALLY ADVANCED TRADERS WILL THRIVE Alexander Franke • Roland Rechtsteiner • Graham Sharp he commodity trading industry is a critical mass in one or more commodities confronting a new, less profitable reality. and the rest of the pack is widening. Within TAfter flatlining for several years, the a few years, the industry will have a different industry’s gross margins in 2016 dipped 4.5 profile – one that is even more dominated by percent to $42 billion, our research shows. the biggest players. (See Exhibit 1.) This decline is setting off a torrent of deal-making and speculation that is transforming the face of commodity WHY BIG MATTERS trading – with examples like Hong Kong-based Noble Group selling part of its business to the The beginning of the endgame started last global energy trader, Vitol; oil trader Gunvor in year with the decline in margins and took off talks with potential acquirers; and Swiss trading in earnest in 2017, as we predicted in our 2016 giant Glencore circling US grain trader Bunge. report, “Reimagining Commodity Trading.” As companies tried to adjust to the industry’s The industry’s endgame has started. From new economics, the clear edge for larger oil to agriculture, building scale is proving operations started to become evident. It didn’t to be the key competitive advantage for the matter if commodity traders had sprawling future. The largest trading companies – both global businesses diversified across various diversified firms and those concentrating commodities or if they specialized in one or two. -

Oil Producers Eye Asia As Western Demand Falters

Oil Producers Eye Asia As Western Demand Falters SPECIAL PDF REPORT SEPTEMBER 2011 An oil rig lights up Cape Town harbour as the sun sets, August 6, 2011. REUTERS/Mike Hutchings Oil price volatility a concern for Asia Indian Oil bars Vitol from tenders-sources Two reasons why Asia's still thirsty for crude: Clyde Russell Iran imports 4-5 cargoes of gasoline per month-sources Litasco 2011 revenue to rise 10 pct -CEO Iran restores fuel oil export vols from Oct COMMODITIESOIL PRODUCERS SHIVER EYE ASIA AFTER AS WESTERNU.S. CREDIT DEMAND DOWNGRADE FALTERS SEPTEMBER AUGUST 20112011 Oil price volatility a concern for Asia SINGAPORE, Sept 8 (Reuters) - il traders have been the only beneficiaries from this year's sharp swings in energy prices, but even they have been caught off guard at times, falling prey to geopolitics and wider financial market risk appetite swings. That sums up reflections at Singapore's Asia Pacific Petroleum Conference (APPEC) this week, where oil traders, O company executives and business leaders gathered to discuss an increasingly turbulent and volatile trading envi- ronment. Three years on from the deepest recession since the Great Depression, oil producers and trading firms continue to look to Asia as the saviour for energy markets, while Europe and the U.S. struggle to sustain an economic recovery. This tension has made oil markets the most volatile since 2009, complicating trading strategies and giving trading houses an overdose of the price fluctuations they normally thrive on. "It's too much volatility and sometimes it's not easy to develop trading strategies," said Tony Nunan, a risk manager with To- kyo-based Mitsubishi Corp on the sidelines of the conference. -

Section C COMMODITY TRADING and FINANCIAL MARKETS

Section C COMMODITY TRADING AND FINANCIAL MARKETS Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Managing risk Funding commodity trading p.3 p.11 2 Section C. Commodity Trading and Financial Markets Chapter Introduction Commodity Trading and Financial Markets INTRODUCTION This guide sets out to present a thumbnail portrait reflected here. Deliberately and inevitably, we have of commodities trading. The aim is to inform readers focused on energy, metals and minerals trading, and about the specialist nature of the business and have made only passing reference to trading the services it provides, as well as to dispel some of agricultural products. the myths that have grown up around trading over We have tried as far as possible to capture factors the years. that are generic to commodity trading firms and It makes clear that this is at its core, a physical their basic functions and techniques. and logistical business, and not the dematerialised, This section drills into the more challenging details speculative activity that is sometimes suggested. of risk management, price-hedging and finance. The Trafigura Group, one of the world’s largest independent commodity traders, with a focus on oil and petroleum products and metals and minerals, is at the centre of the narrative. The company focus is designed to provide concrete case studies and illustrations. We do not claim that this is a definitive guide to all facets of the industry. Other firms than Trafigura will have their own unique characteristics, which are not 3 Section C. Commodity Trading and Financial Markets Chapter 10. Managing risk Chapter 10 MANAGING RISK Risk management is a core competence for trading firms. -

Mexico in the Time of COVID-19: an OPIS Primer on the Impact of the Virus Over the Country’S Fuel Market

Mexico in the Time of COVID-19: an OPIS Primer on the Impact of the Virus Over the Country’s Fuel Market Your guide to diminishing prices and fuel demand Mexico in the Time of COVID-19 Leading Author Daniel Rodriguez Table of Contents OPIS Contributors Coronavirus Clouds Mexico’s Energy Reform ................................................................1 Justin Schneewind Eric Wieser A Historic Demand Crash ....................................................................................................2 OPIS Editors IHS Markit: Worst Case Drops Mexico’s Gasoline Sales to 1990 levels ...................3 Lisa Street Bridget Hunsucker KCS: Mexico Fuel Demand to Drop Up to 50% .............................................................4 IHS Markit ONEXPO: Retail Sales Drop 60% ......................................................................................4 Contirbuitors Carlos Cardenas ONEXPO: A Retail View on COVID-19 Challenges..........................................................5 Debnil Chowdhury Felipe Perez IHS Markit: USGC Fuel Prices to Remain Depressed Into 2021 .................................6 Kent Williamson Dimensioning the Threat ....................................................................................................7 Paulina Gallardo Pedro Martinez Mexico Maps Timeline for Returning to Normality ......................................................7 OPIS Director, Tales of Two Quarantines ...................................................................................................8 Refined -

Redstone Commodity Update Q4 2020

Welcome to the Redstone Commodity Update 2020: Q4 Welcome to the Redstone Commodity Moves Update Q4 2020, a very interesting period to report on as Redstone witnessed the busiest quarter of the year so far. This is exactly the opposite to what we have witnessed in previous years, the stronger than usual recruitment drive was very much spear headed by a particularly strong showing in the energy space which in turn was led by energy recruitment activity within the EMEA region which we shall cover below. Overall EMEA saw the largest volume of moves in each of the covered sections with the Americas outperforming Asia consistently outside of the Shipping and Bunker space. Overall as we enter 2021 right across the board commodities markets seem to be entering a bullish period with talk of a new super cycle driven by green led commodities and energy. The early signs for 2021 from a recruitment standpoint seem quite positive with many companies who held back last year making early approaches for recruitment projects, many buoyed by the rollout of various Covid-19 vaccines. The certainty around Brexit and the US election allows people to make their plans accordingly with the remaining ongoing issues (such disruption in the US relating to fallout from the election and a serious uptick in Corona cases throughout the western world / new strains etc) seemingly not putting investors off, as at least in the medium term, we can see the light at the end of the tunnel. Noteworthy Energy Talent Moves EMEA saw the greatest volume of moves in Q4 2020 further extending the volumes previously witnessed in terms of both total number of moves reported and as a percentage share of total moves tracked, within this we can see a particularly strong performance for all things power, gas or LNG related, as European power and gas markets provide ROI’s that are too attractive to ignore.