17-2233, Document 114, 11/01/2017, 2162193, Page1 of 93 RECORD NO

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Middle East Oil Pricing Systems in Flux Introduction

May 2021: ISSUE 128 MIDDLE EAST OIL PRICING SYSTEMS IN FLUX INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................................................ 2 THE GULF/ASIA BENCHMARKS: SETTING THE SCENE...................................................................................................... 5 Adi Imsirovic THE SHIFT IN CRUDE AND PRODUCT FLOWS ..................................................................................................................... 8 Reid l'Anson and Kevin Wright THE DUBAI BENCHMARK: EVOLUTION AND RESILIENCE ............................................................................................... 12 Dave Ernsberger MIDDLE EAST AND ASIA OIL PRICING—BENCHMARKS AND TRADING OPPORTUNITIES......................................... 15 Paul Young THE PROSPECTS OF MURBAN AS A BENCHMARK .......................................................................................................... 18 Michael Wittner IFAD: A LURCHING START IN A SANDY ROAD .................................................................................................................. 22 Jorge Montepeque THE SECOND SPLIT: BASRAH MEDIUM AND THE CHALLENGE OF IRAQI CRUDE QUALITY...................................... 29 Ahmed Mehdi CHINA’S SHANGHAI INE CRUDE FUTURES: HAPPY ACCIDENT VERSUS OVERDESIGN ............................................. 33 Tom Reed FUJAIRAH’S RISE TO PROMINENCE .................................................................................................................................. -

Vitol-Brochure-2019 FINAL-1.Pdf

02 VITOL | Contents Vitol 04 VLC Renewables 14 Vitol at a glance 05 Our investments 16 Operating Globally 08 VTTI 17 Trading portfolio 10 Vitol Aviation 17 Crude oil 10 Viva Energy 18 Middle distillates 10 Vivo Energy 18 Gasoline 10 Petrol Ofisi 19 Biofuel 11 OVH Energy 19 Fuel oil 11 VARO 20 Naphtha 12 Rodoil 20 Bitumen 12 Hascol 20 Coal 13 Cockett Marine Oil 20 Liquid petroleum gas (LPG) 13 VPI Immingham 21 Liquefied natural gas (LNG) 13 VLC Renewables 21 Natural gas 13 Exploration and production 24 Power 14 Vitol Foundation 25 Renewables 14 Our worldwide capabilities 26 Shipping 14 VITOL VITOL | 03 Vitol Vitol is at the For over 50 years Vitol has served the Responsibility heart of the world’s world’s energy markets, trading over We are mindful of the risks associated seven million barrels of crude oil and with handling energy. Our assets energy flows. Every products a day and delivering energy operate to international HSE standards day we use our products to countries worldwide. and we expect the same of our partners expertise and throughout the energy chain. We seek logistical networks Our customers include national oil to conduct our business in line with to distribute energy companies, multinationals, leading the ten principles of the UN Global industrial and chemical companies and Compact and to work with partners around the world, the world’s largest airlines. We deliver who share our commitment to high efficiently and the products they need on time and to standards of operation. responsibly. specification by sourcing and managing the movement of energy through the relevant infrastructures. -

Global Energy 2012 Conference & Exhibition

GLOBAL 12 ENERGY 20 29/30/31 OCTOBER 2012 HOTEL PRESIDENT WILSON Global Energy Geneva 2012 Where the oil & gas trade meets...with key participation of Cargill, Gunvor, Lundin, Lukoil, Mercuria, Socar, Trafigura To register: www.globalenergygeneva.com GLOBAL 12 ENERGY 20 GLOBAL ENERGY 2012 CONFERENCE & EXHIBITION 29/30/31 October 2012, Hotel President Wilson, Geneva T: +41 (0) 22 321 74 80 | F: +41 (0) 22 321 74 82 | E: [email protected] | www.globalenergygeneva.com About Global Energy 2012 The oil and gas trade is critical to the global economy and the effect of energy prices and trade is more profound than for any other traded commodity. Global Energy is a trade show, conference and exhibition unique to Geneva. Global Energy 2012 is being held on October 29/30/31 at the prestigious Hotel President Wilson in the heart of Geneva. The event brings together energy traders, banks, policymakers, delivering important keynote speeches and panel debates. Global Energy 2012 takes place during an important week in the Geneva commodities trade calendar. It will be attended by a “who’s who” in oil and gas in Switzerland and abroad. Who will attend Global Energy 2012? Major international oil & gas trading firms Traders from small and medium-sized firms throughout the globe Leaders in the Swiss energy trade community Upstream oil and gas majors – interested in the global S&D of oil and gas Oil and gas investors, including family offices and private banks Trade financiers specialising in oil and gas Professional firms: lawyers, advisory/management -

Corporate-Brochure 2020.Pdf

02 VITOL | Contents Vitol 04 VLC Renewables 14 Vitol at a glance 05 Our investments 16 Operating Globally 08 VTTI 17 Trading portfolio 10 Vitol Aviation 17 Crude oil 10 Viva Energy 18 Middle distillates 10 Vivo Energy 18 Gasoline 10 Petrol Ofisi 19 Biofuel 11 OVH Energy 19 Fuel oil 11 VARO 20 Naphtha 12 Rodoil 20 Bitumen 12 Hascol 20 Coal 13 Cockett Marine Oil 20 Liquid petroleum gas (LPG) 13 VPI Immingham 21 Liquefied natural gas (LNG) 13 VLC Renewables 21 Natural gas 13 Exploration and production 24 Power 14 Vitol Foundation 25 Renewables 14 Our worldwide capabilities 26 Shipping 14 VITOL VITOL | 03 Vitol Vitol is at the For over 50 years Vitol has served the Responsibility world’s energy markets, trading over We are mindful of the risks associated heart of the world’s eight million barrels of crude oil and with handling energy. Our assets energy flows. Every products a day and delivering energy operate to international HSE standards day we use our products to countries worldwide. and we expect the same of our partners expertise and throughout the energy chain. We seek logistical networks Our customers include national oil to conduct our business in line with to distribute energy companies, multinationals, leading the ten principles of the UN Global industrial and chemical companies and Compact and to work with partners around the world, the world’s largest airlines. We deliver who share our commitment to high efficiently and the products they need on time and to standards of operation. responsibly. specification by sourcing and managing the movement of energy through the relevant infrastructures. -

Oil and Gas News Briefs, December 3, 2018

Oil and Gas News Briefs Compiled by Larry Persily December 3, 2018 First Nation approves benefits agreements for LNG project in B.C. (Vancouver Sun; Nov. 29) - It wasn’t an easy decision for the Squamish First Nation to approve the C$1.6 billion Woodfibre LNG project 35 miles north of Vancouver, B.C., according to a spokesman, but it came with potential benefits of cash and land. The First Nation council approved three economic benefits agreements last week — one each with Woodfibre LNG, pipeline company FortisBC and the province, “contingent on the environmental conditions being met,” according to a news release Nov. 29. The 40-year agreements include cash totaling C$225.65 million, 1,600 short-term and 330 long-term jobs, business opportunities, and land transfers of almost 1,100 acres. “Communities are sometimes faced with difficult decisions and it is recognized that this was a difficult decision for many,” said Squamish Councillor Khelsilem, whose English name is Dustin Rivers. “As agreed by the proponents, we will be co-developing management plans for the project and will have our own monitors on the ground to report on any non-compliance with cultural, employment, and training conditions.” Work is expected to start next fall at the former pulp mill site. At full operation, the plant will be capable of making 2.1 million tonnes of LNG per year. The money will be paid to the First Nation at project milestones, including the start of construction and start of operations. Other payments will go toward a cultural fund for the Indigenous community and training and education programs. -

Vitol Pays $164 Mln to Resolve U.S. Allegations of Oil Bribes in Latin

December 4, 2020 Vitol pays $164 mln to resolve U.S. allegations of according to the DOJ statement. oil bribes in Latin America Prosecutors said the bribes went to employees at Mexico's Vitol Group's U.S. subsidiary agreed to pay $164 state-run Pemex and Ecuadorian state oil company million to resolve probes by the U.S. government that Petroecuador. the energy trader paid bribes in Brazil and other Petroecuador and Pemex did not respond to requests for countries to boost its oil trading business, the U.S. comment. Department of Justice said on Thursday. Brazilian prosecutors announced in late 2018 that they Under a three-year deferred prosecution agreement, were investigating Petrobras' oil deals with trading houses, the Swiss trading firm admitted guilt and agreed to including the world's biggest oil traders - Vitol, Trafigura improve internal reporting and compliance functions. and Glencore. Vitol, run out of London, is the world's largest In early 2019, the DOJ opened its own probe into the three independent oil trader, trading some 8 million barrels company's dealings in Brazil. The FBI investigated two key of oil a day. Vitol executives who were overseeing the region during "Vitol paid bribes to government officials in Brazil, those years, including the head of Vitol's U.S. arm, Michael Ecuador and Mexico to win lucrative business "Mike" Loya, who retired earlier this year. contracts and obtain competitive advantages to which Loya did not immediately respond to a message sent to his they were not fairly entitled," Acting U.S. Attorney LinkedIn account. -

Redstone Commodity Update Q3

Welcome to the Redstone Commodity Update 2020: Q3 Welcome to the Redstone Commodity Moves Update Q3 2020, another quarter in a year that has been strongly defined by the pandemic. Overall recruitment levels across the board are still down, although we have seen some pockets of hiring intent. There appears to be a general acknowledgement across all market segments that growth must still be encouraged and planned for, this has taken the form in some quite senior / structural moves. The types of hires witnessed tend to pre-empt more mid-junior levels hires within the same companies in following quarters, which leaves us predicting a stronger than expected finish to Q4 2020 and start to Q1 2021 than we had previously planned for coming out of Q2. The highest volume of moves tracked fell to the energy markets, notably, within power and gas and not within the traditional oil focused roles, overall, we are starting to see greater progress towards carbon neutrality targets. Banks such as ABN, BNP and SocGen have all reduced / pulled out providing commodity trade finance, we can expect competition for the acquiring of finance lines to heat up in the coming months until either new lenders step into the market or more traditional lenders swallow up much of the market. We must also be aware of the potential impact of the US elections on global trade as countries such as Great Britain and China (amongst others) await the outcome of the impending election. Many national trade strategies and corporate investment strategies will hinge on this result in a way that no previous election has. -

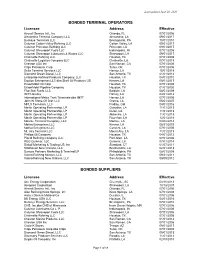

Bonded Terminal Operators

Last updated June 26, 2020 BONDED TERMINAL OPERATORS Licensee Address Effective Aircraft Service Intl., Inc Orlando, FL 07/01/2006 Alexandria Terminal Company LLC Alexandria, LA 09/01/2017 Buckeye Terminals LLC Breinigsville, PA 10/01/2010 Calumet Cotton Valley Refining LLC Cotton Valley, LA 09/01/2017 Calumet Princeton Refining LLC Princeton, LA 09/01/2017 Calumet Shreveport Fuels LLC Indianapolis, IN 07/01/2006 Calumet Shreveport Lubricants & Waxes LLC Shreveport, LA 09/01/2017 Chalmette Refining LLC Houston, TX 07/01/2006 Chalmette Logistics Company LLC Chalmette, LA 07/01/2018 Chevron USA Inc San Ramon, CA 07/01/2006 Citgo Petroleum Corp Tulsa, OK 07/01/2006 Delta Terminal Services LLC Harvey, LA 10/01/2018 Diamond Green Diesel, LLC San Antonio, TX 01/01/2014 Enterprise Refined Products Company, LLC Houston, TX 04/01/2010 Equilon Enterprises LLC dba Shell Oil Products US Kenner, LA 05/01/2017 ExxonMobil Oil Corp Houston, TX 07/01/2006 ExxonMobil Pipeline Company Houston, TX 01/01/2020 Five Star Fuels, LLC Baldwin, LA 08/01/2009 IMTT-Gretna Harvey, LA 04/01/2012 International-Matex Tank Terminals dba IMTT Harvey, LA 07/01/2006 John W Stone Oil Dist, LLC Gretna, LA 05/01/2007 MPLX Terminals, LLC Findlay, OH 04/01/2016 Martin Operating Partnership, LP Gueydan, LA 11/01/2013 Martin Operating Partnership, LP Dulac, LA 11/01/2013 Martin Operating Partnership, LP Abbeville, LA 11/01/2013 Martin Operating Partnership, LP Fourchon, LA 12/01/2016 Monroe Terminal Company, LLC Monroe, LA 04/08/2014 Motiva Enterprises LLC Kenner, LA 08/21/2009 Motiva Enterprises LLC Convent, LA 07/01/2006 Mt. -

Financing Options in the Oil and Gas Industry, Practical Law UK Practice Note

Financing options in the oil and gas industry, Practical Law UK Practice Note... Financing options in the oil and gas industry by Suzanne Szczetnikowicz and John Dewar, Milbank, Tweed, Hadley & McCloy LLP and Practical Law Finance. Practice notes | Maintained | United Kingdom Scope of this note Industry overview Upstream What is an upstream oil and gas project? Typical equity structure Relationship with the state Key commercial contracts in an upstream project Specific risks in financing an upstream project Sources of financing in the upstream sector Midstream, downstream and integrated projects Typical equity structures What is a midstream oil and gas project? Specific risks in financing a midstream project What is a downstream oil and gas project? Specific risks in financing a downstream project Integrated projects Sources of financing in midstream, downstream and integrated projects Multi-sourced project finance Shareholder funding Equity bridge financing Additional sources of financing Other financing considerations for the oil and gas sectors Expansion financings Hedging Refinancing Current market trends A note on the structures and financing options and risks typically associated with the oil and gas industry. © 2018 Thomson Reuters. All rights reserved. 1 Financing options in the oil and gas industry, Practical Law UK Practice Note... Scope of this note This note considers the structures, financing options and risks typically associated with the oil and gas industry. It is written from the perspective of a lawyer seeking to structure a project that is capable of being financed and also addresses the aspects of funding various components of the industry from exploration and extraction to refining, processing, storage and transportation. -

Amici Brief File Stamped 020718(Pdf)

Case 17-2233, Document 173-2, 02/07/2018, 2231672, Page1 of 39 17-2233 IN THE United States Court of Appeals FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT >> >> PRIME INTERNATIONAL TRADING LTD., ON BEHALF OF ITSELF AND ALL OTHERS SIMILARLY SITUATED, WHITE OAKS FUND LP, ON BEHALF OF ITSELF AND ALL OTHERS SIMILARLY SITUATED, KEVIN MCDONNELL, ON BEHALF OF THEMSELVES AND ALL OTHERS SIMILARLY SITUATED,ANTHONY INSINGA, AND ALL OTHERS SIMILARLY SITUATED, ROBERT MICHIELS, ON BEHALF OF THEMSELVES AND ALL OTHERS SIMILARLY SITUATED, JOHN DEVIVO, ON BEHALF OF THEMSELVES AND ALL OTHERS SIMILARLY SITUATED, NEIL TAYLOR, AARON SCHINDLER, PORT 22, LLC, ATLANTIC TRADING USA LLC, XAVIER LAURENS, ON BEHALF OF THEMSELVES AND ALL OTHERS SIMILARLY SITUATED, Plaintiffs-Appellants, (caption continued on inside cover) On Appeal from the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York BRIEF FOR THE CHAMBER OF COMMERCE OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, THE SECURITIES INDUSTRY AND FINANCIAL MARKETS ASSOCIATION, THE INTERNATIONAL SWAPS AND DERIVATIVES ASSOCIATION, AND THE FUTURES INDUSTRY ASSOCIATION AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF DEFENDANTS-APPELLEES AND AFFIRMANCE GEORGE T. CONWAY III WACHTELL, LIPTON, ROSEN & KATZ 51 West 52nd Street New York, New York 10019 (212) 403–1000 Attorneys for Amici Curiae Case 17-2233, Document 173-2, 02/07/2018, 2231672, Page2 of 39 MICHAEL SEVY, ON BEHALF OF HIMSELF AND ALL OTHERS SIMILARLY SITUATED, GREGORY H. SMITH, INDIVIDUALLY AND ON BEHALF OF ALL OTHERS SIMILARLY SITUATED, PATRICIA BENVENUTO, ON BEHALF OF HERSELF AND ALL OTHERS SIMI- -

2017 Greenhouse Gas Inventory Tables and Figures

2017 Greenhouse Inventory June 2018 Prepared by: Puget Sound Energy Prepared by: Puget Sound Energy 2017 Greenhouse Inventory TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................. 3 1.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................. 4 1.1 Purpose ........................................................................................... 4 1.2 Inventory Organization .................................................................... 4 2.0 BACKGROUND .............................................................................. 5 2.1 Regulatory Actions .......................................................................... 5 2.2 Inventory and GHG Reporting Compliance ..................................... 6 3.0 MAJOR ACCOUNTING ISSUES .................................................... 7 4.0 BOUNDARIES AND SOURCES ..................................................... 8 4.1 Organizational Boundaries .............................................................. 8 4.1.1 Electrical Operations .............................................................................................. 8 4.1.2 Natural Gas Operations ......................................................................................... 8 4.2 Operational Boundaries .................................................................. 9 4.2.1 Scope I (Direct Emissions) .................................................................................... -

Commodities Price Volatity in the 2000S Unpacking Financialisation Samuel K

Commodities Price Volatity in the 2000s Unpacking financialisation Samuel K. GAYI Special Unit on Commodities UNCTAD 0utline • Context – Price trends, 1960-2011 • New twists • Financialization – What is it? – Some concerns – Evidence – UNCTAD vs others • Refocus on fundamentals • Concluding remarks Context Overview of Price trends 1960-2011 Fig. 1: Non oil commodity price index in constant terms, 1960-2011 (2000 = 100) Fig. 2: Historical commodity real price indices, 1960-2011 600 500 400 300 Real price index, 2000=100 index, price Real 200 100 - 1960 1963 1966 1969 1972 1975 1978 1981 1984 1987 1990 1993 1996 1999 2002 2005 20082011e Food Tropical beverages Agricultural Raw Materials Minerals, Ores and Metals Crude petroleum Overview of price trends, 1960-2011 • Since 1960: real prices of non-fuel commodities relatively stable (highest peak in 1974 - oil shock); • 1980-2000: commodity prices volatile, but generally declined with temporary peaks in 1988 and 1997. • 1997—1999: Asian crisis contributed to slump in US $ prices for primary commodities of 20% (compared to 5% for manufactures) (Page & Hewitt, 2001); • By mid-2008, commodities had enjoyed 5-year price boom - longest & broadest rally of the post-World War II period, i.e., after almost 30 years of generally low but moderately fluctuating prices. • Relatively well established that there is a long-term downward decline in the relative prices of primary commodities vis-à-vis manufactures (Maizels, 1992). Overview of price trends (ii) • Since 1960, two major commodity price booms (1973-1980, & 2003- 2011); • Current (recent?) commodity price boom is different from 1970s boom. Note:1970s commodity price spikes were short- lived (Radetzki 2006; Kaplinsky and Farooki, 2009); • Historical data: significantly higher real prices for beverages and food commodities were recorded in the 1970s, relative to 2003 to 2011; • However, rise in commodity prices 2003-11, especially from 2006 to 2008, is particularly pronounced in the case of metals, crude oil and food (Fig.