University of Zagreb Faculty of Humanities and Social

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Markets of Mediterranean

N A E THE MARKETS OF THE N A R R E T I MEDITERRANEAN D E Management Models and Good Practices M E H T F O S T E K R A M E H T THE MARKETS OF THE MEDITERRANEAN Management Models and Good Practices This study, an initiative of the Institut Municipal de Mercats INSTITUT MUNICIPAL DE MERCATS DE BARCELONA de Barcelona, has been possible thanks to the support of Governing Council the European Union through the Med Programme that has Raimond Blasi, President funded the MedEmporion project, promoted by the cities Sònia Recasens, Vice-President of Barcelona,Turin, Genoa and Marseilles. Gerard Ardanuy Mercè Homs Published by Jordi Martí Institut Municipal de Mercats de Barcelona Sara Jaurrieta Coordination Xavier Mulleras Oscar Martin Isabel Ribas Joan Laporta Texts Jordi Joly Genís Arnàs | Núria Costa | Agustí Herrero | Oscar Martin | Albert González Gerard Navarro | Oscar Ubide Bernat Morales Documentation Salvador Domínguez Joan Ribas | Marco Batignani and Ursula Peres Verthein, from Alejandro Goñi the Observatori de l’Alimentació (ODELA) | Research Centre Faustino Mora at the Universitat de Barcelona Joan Estapé Josep Lluís Gil Design and Layout Eva Maria Gajardo Serveis Editorials Estudi Balmes Lluís Orri Translation Jordi Torrades, Manager Neil Charlton | Pere Bramon Manel Armengol, Secretary Antonio Muñoz, Controller Photographs Jordi Casañas | Núria Costa Managing Board Jordi Torrades, Manager Acknowledgements Francisco Collados, Director of the Economic and Financial Service The Institut de Mercats de Barcelona wishes to thank all the Manel -

Hellozagreb5.Pdf

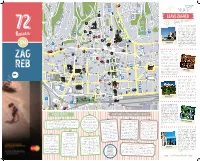

v ro e H s B o Šilobodov a u r a b a v h Put o h a r r t n e e o i k ć k v T T c e c a i a i c k Kozarčeve k Dvor. v v W W a a a Srebrnjak e l Stube l St. ć č Krležin Gvozd č i i s ć Gajdekova e k Vinogradska Ilirski e Vinkovićeva a v Č M j trg M l a a a Zamen. v č o e Kozarčeva ć k G stube o Zelengaj NovaVes m Vončinina v Zajčeva Weberova a Dubravkin Put r ić M e V v Mikloušić. Degen. Iv i B a Hercegovačka e k Istarska Zv k u ab on ov st. l on ar . ić iće Višnjica . e va v Šalata a Kuhačeva Franje Dursta Vladimira Nazora Kožarska Opatička Petrova ulica Novakova Demetrova Voćarska Višnjičke Ribnjak Voćarsko Domjanićeva stube naselje Voćarska Kaptol M. Slavenske Lobmay. Ivana Kukuljevića Zamenhoova Mletač. Radićeva T The closest and most charming Radnički Dol Posil. stube k v Kosirnikova a escape from Zagreb’s cityŠrapčeva noise e Jadranska stube Tuškanac l ć Tuškanac Opatovina č i i is Samobor - most joyful during v ć e e Bučarova Jurkovićeva J. Galjufa j j Markov v the famous Samobor Carnival i i BUS r r trg a Ivana Gorana Kovačića Visoka d d andJ. Gotovca widely known for the cream Bosanska Kamenita n n Buntićeva Matoševa A A Park cake called kremšnita. Maybe Jezuitski P Pantovčak Ribnjak Kamaufova you will have to wait in line to a trg v Streljačka Petrova ulica get it - many people arrive on l Vončinina i Jorgov. -

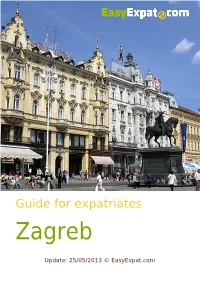

Guide for Expatriates Zagreb

Guide for expatriates Zagreb Update: 25/05/2013 © EasyExpat.com Zagreb, Croatia Table of Contents About us 4 Finding Accommodation, 49 Flatsharing, Hostels Map 5 Rent house or flat 50 Region 5 Buy house or flat 53 City View 6 Hotels and Bed and Breakfast 57 Neighbourhood 7 At Work 58 Street View 8 Social Security 59 Overview 9 Work Usage 60 Geography 10 Pension plans 62 History 13 Benefits package 64 Politics 16 Tax system 65 Economy 18 Unemployment Benefits 66 Find a Job 20 Moving in 68 How to look for work 21 Mail, Post office 69 Volunteer abroad, Gap year 26 Gas, Electricity, Water 69 Summer, seasonal and short 28 term jobs Landline phone 71 Internship abroad 31 TV & Internet 73 Au Pair 32 Education 77 Departure 35 School system 78 Preparing for your move 36 International Schools 81 Customs and import 37 Courses for Adults and 83 Evening Class Passport, Visa & Permits 40 Language courses 84 International Removal 44 Companies Erasmus 85 Accommodation 48 Healthcare 89 2 - Guide for expats in Zagreb Zagreb, Croatia How to find a General 90 Practitioner, doctor, physician Medicines, Hospitals 91 International healthcare, 92 medical insurance Practical Life 94 Bank services 95 Shopping 96 Mobile Phone 99 Transport 100 Childcare, Babysitting 104 Entertainment 107 Pubs, Cafes and Restaurants 108 Cinema, Nightclubs 112 Theatre, Opera, Museum 114 Sport and Activities 116 Tourism and Sightseeing 118 Public Services 123 List of consulates 124 Emergency services 127 Return 129 Before going back 130 Credit & References 131 Guide for expats in Zagreb - 3 Zagreb, Croatia About us Easyexpat.com is edited by dotExpat Ltd, a Private Company. -

Zagreb Winter 2016/2017

Maps Events Restaurants Cafés Nightlife Sightseeing Shopping Hotels Zagreb Winter 2016/2017 Trešnjevka Where wild cherries once grew Go Gourmet A Croatian feast Shopping Cheat Sheet Find your unique item N°86 - complimentary copy zagreb.inyourpocket.com Festive December Contents in Ljubljana ESSENTIAL CITY G UIDES Foreword 4 Sightseeing 46 A word of welcome Snap, camera, action Arrival & Getting Around 6 Zagreb Pulse 53 We unravel the A to Z of travel City people, city trends Zagreb Basics 12 Shopping 55 All the things you need to know about Zagreb Ready for a shopping spree Trešnjevka 13 Hotels 61 A city district with buzz The true meaning of “Do not disturb” Culture & Events 16 List of Small Features Let’s fill up that social calendar of yours Advent in Zagreb 24 Foodie’s Guide 34 Go Gourmet 26 Festive Lights Switch-on Event City Centre Shopping 59 Ćevap or tofu!? Both! 25. Nov. at 17:15 / Prešernov trg Winter’s Hot Shopping List 60 Restaurants 35 Maps & Index Festive Fair Breakfast, lunch or dinner? You pick... from 25. Nov. / Breg, Cankarjevo nabrežje, Prešernov in Kongresni trg Street Register 63 Coffee & Cakes 41 Transport Map 63 What a pleasure City Centre Map 64-65 St. Nicholas Procession City Map 66 5. Dec. at 17:00 / Krekov trg, Mestni trg, Prešernov trg Nightlife 43 Bop ‘till you drop Street Theatre 16. - 20. Dec. at 19:00 / Park Zvezda Traditional Christmas Concert 24. Dec. at 17:00 / in front of the Town Hall Grandpa Frost Proccesions 26. - 30. Dec. at 17:00 / Old Town New Year’s Eve Celebrations for Children 31. -

Esplanade Zagreb Hotel Fact Sheet

Press Release – Fact Sheet – Esplanade Zagreb Hotel 2018 Esplanade Zagreb Hotel Fact Sheet ADDRESS: Esplanade Zagreb Hotel, Mihanovićeva 1, 10000 Zagreb, Croa tia CONTACT: Tel: +385 1 4566 666 Fax: +385 1 4566 050 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.esplanade.hr YEAR OF OPENING: 1925 LAST RENOVATION: 2004 INTERIOR DESIGN: MKV Design, London, Maria K. Vafiadis GENERAL MANAGER: Ivica Max Krizmanić EXECUTIVE CHEF: Ana Grgić SHAREPOINT PHOTO ACCESS: https://esplanadehr.sharepoint.com/:f:/g/marketing/EqcnGanZgQ1Am- eDuQTE2TMBF_8PXdfVFQxlgyOUuKCnLg?e=Nx1nnR Location: The Esplanade Zagreb Hotel, situated in the heart of this historic city, is an art deco icon revered throughout the region and lauded for its impeccable standards of service. Dating back to 1925, the Esplanade has always been at the heart of Zagreb’s social scene and can count presidents, politicians, film and music stars among its many distinguished guests. Its famous Oleander terrace was once described as where ‘the Balkans end and where civilization begins’. The hotel, reopened in 2004 after a complete renovation, is designed to seamlessly merge the best modern comforts with art deco tradition. Zagreb is a blend of Baroque, Austro-Hungarian architecture, art nouveau, art deco, and contemporary design. It has been central to the zeitgeist of style for well over a hundred years. Accommodation: ⋅ 208 spacious and beautifully furnished rooms that capture the history of the building, seamlessly blending in contemporary touches. All rooms have free-to-use hard-wired and wireless Internet access, in-room movies, and personal bars. ⋅ 146 Superior rooms averaging 28 sqm. Elegantly and tastefully decorated with marble bathrooms with bathtubs and walk-in showers, luxurious toiletries, and fluffy bathrobes. -

ZAGREB Written Series of Guidebooks.” the New York Times

Hotels Restaurants Cafés Nightlife Sightseeing Events Maps “In Your Pocket: A cheeky, well- ZAGREB written series of guidebooks.” The New York Times October - November 2009 It’s our birthday! Gifts and specials to celebrate! It’s Autumn Perfect to sip on wine, nibble on cheese, fresh air... N°50 - complimentary copy zagreb.inyourpocket.com Culture Almanac Take a breakfast and cultural tour around the city with us! CONTENTS 3 ESSENTIAL CITY GUIDES Contents Arriving in Zagreb 6 Your first view of the capital city The Basics 7 More than just climate stats (not much) History 8 Kings, queens, rooks and pawns Culture & Events 9 Interesting and boring stuff included Autumn in Zagreb 24 Golden leaves, ruby wine, feelin‘ fine! Where to stay 28 The sounds of trumpets will add to the spice of life at the Vip Jazzg A place to rest your weary head Festival! See page 20. Dining & Nightlife 35 Lions, wolves and bear cubs welcome Sightseeing What to see 46 Cafés 40 All those things you mustn’t miss Easily the best scene in the world! Mail & Phones Nightlife 42 Smoke signals and carrier pigeons 50 When you just gotta boogie Getting around 51 Save on shoe leather Transport map 53 Directory Shopping 54 Helping you get rid of that extra cash Lifestyle Directory 56 The most essential support Business Directory 59 Become a millionaire in no time Maps & Index Street index 61 City centre map 62 City map 64 Autumn is here and there is not better time to savour a drop of fresh Country map 65 young wine as it gets blessed in and around the different counties of Zagreb on Martinje - a traditional day dedicated to St. -

Explore the Most Beautiful Outdoor Farmers' Market

Powered by THURSDAY / 08 JUNE / 2017 | YEAR 2 | ISSUE 07 FREE COPY DOLAC Explore the most beautiful outdoor farmers’ market recommended by locals INSIDERS' TIPS FOR RESTAURANTS, MUSEUMS, BARS, NIGHT CLUBS... MARKO MIŠČEVIĆ/HANZAMARKO MEDIA discover your story at croatia.hr Don´t fill your life with days, fill your days with life. photo by zoran jelača CONTENTS ISSUE 07 l YEAR 2 l THURSDAY / 08 JUNE / 2017 06 IMPRESSUM PUBLISHER: 18 04 HANZA MEDIA d.o.o. Koranska 2, Zagreb events 18 DOLAC visit OIB: 791517545745 Dolac is Zagreb's central farmers' EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: 4 SUMMER AT THE MUSEUM 34 SLJEME Goran Ogurlić market, located between the church OF CONTERPORARY ART [email protected] of St. Mary and Kaptol. If you want The highest peak of Medvednica A very succesful combination of to get to know real Zagreb and Nature Park, rising over Zagreb at EDITOR: music, art and film for the first time itsinhabitants, you have to visit their 1033m Viktorija Macukić includes unique art performances market known for best homemade [email protected] 37 SECRET ADVENTURES produce 6 THIS WEEK HOT LIST CREATIVE DIRECTOR: Landed solar sistem Borna Križančić 20 FUN WITH KIDS Don't miss the chance to see pre- [email protected] war Zagreb fashion, music and Zagreb offers great variety of places explore GRAPHICS EDITORS: lifestyle in Maksimir park, take that children will enjoy Hrvoje Netopil i a walk down Kurelčeva, a wine 38 TRIP TO ISTRIA Žaneta Zjakić lover's street map Unique gourmet experience and TRANSLATION: Romana Pezić -

Generalni Urbanistički Plan Grada Zagreba Izmjene I Dopune 2016

GRADZAGREB GRADSKI URED ZA STRATEGIJSKO PLANIRANJE I RAZVOJ GRADA Ulica Republike Austrije 18, Zagreb ZAVOD ZA PROSTORNO UREĐENJE GRADA ZAGREBA Ulica Republike Austrije 18_10 000 Zagreb_www.zzpugz.hr GENERALNI URBANISTIČKI PLAN GRADA ZAGREBA IZMJENE I DOPUNE 2016. TEKSTUALNI DIO PLANA KNJIGA I - ODREDBE ZA PROVOĐENJE SVIBANJ, 2016. NAZIV ELABORATA: GENERALNI URBANISTIČKI PLAN GRADA ZAGREBA IZMJENE I DOPUNE 2016. TEKSTUALNI DIO PLANA KNJIGA I - ODREDBE ZA PROVOĐENJE NOSITELJ IZRADE PLANA: GRAD ZAGREB GRADSKI URED ZA ZA STRATEGIJSKO PLANIRANJE I RAZVOJ GRADA PROČELNIK: p.o. gradonačelnika Grada Zagreba pomoćnica pročelnika Jadranka Veselić Bruvo, dipl.ing.arh. ODGOVORNA OSOBA ZA PROVOĐENJE JAVNE RASPRAVE: Ankica Pavlović, dipl.ing.arh. IZRAĐIVAČ PLANA: ZAVOD ZA PROSTORNO UREĐENJE GRADA ZAGREBA RAVNATELJ: vršitelj dužnosti ravnatelja Ivica Rovis, dipl.iur. ODGOVORNI VODITELJ IZRADE PLANA: Sanja Šerbetić Tunjić, dipl.ing.arh. STRUČNI TIM: Dragica Barešić, dipl.ing.arh. Mirela Bokulić Zubac, dipl.ing.arh. Marija Brković, bacc.oec. Maja Bubrić, građ.teh. Martina Čavlović, dipl.iur. Ivica Fanjek, dipl.ing.arh. Boris Gregurić, dipl.ing.arh. Ivan Lončarić, prof.geog. i pov. Dubravka – Petra Lubin, dipl.ing.arh. Tomislav Mamić Katica Mihanović, dipl. ing šum. Nives Mornar, dipl.ing.arh. Jasmina Doko, dipl.ing.agr. Vladimir Ninić, dipl.ing.građ. Larisa Nukić Alen Pažur, mag.geog. Zoran Radovčić, dipl.oec. Ana - Marija Rajčić, dipl.ing.arh. Lidija Sekol, dipl.ing.arh. Jasmina Sirovec Vanić, dipl.ing.arh. Sabina Pavlić, dipl.ing.arh. Sanja Šerbetić Tunjić, dipl.ing.arh. Dubravko Širola, dipl.ing.prom. Dubravka Žic, dipl.ing.arh. GENERALNI URBANISTIČKI PLAN GRADA ZAGREBA, IZMJENE I DOPUNE 2016. GRAD ZAGREB GENERALNI URBANISTIČKI PLAN GRADA ZAGREBA – IZMJENE I DOPUNE 2015. -

Step by Step

en jabukovac ulica josipa torbara kamenjak upper town medveščak ulica nike grškovića nova ves tuškanac 8 opatička street Stroll along the splendid palaces that line this 10 croatian history ancient street, from the jurjevska ulica museum three-winged palace that’s ul. baltazara dvorničića medvedgradska ulica Soak up this stunning home to the Croatian krležin gvozd Institute of History (at mirogoj cemetery showcase of Baroque, the 7 stone gate → 10 minutes by bus from Kaptol Vojković-Oršić-Kulmer- #10) to the neo-classical Rauch Palace built in the palace of the aristocratic Light a candle and take in the silence inside the only city gate Meander around the maze of walking paths that 18th century. Once the “it” Drašković family (at #18). preserved since the Middle Ages, a place of worship for the crisscross this monumental cemetery, opened in spot for the city’s elite Check out the Zagreb City devout from all over Croatia. First mentioned in the medieval 1876 and today Croatia’s largest. Shaded by tall trees who gathered in its grand Museum inside the former times, the gate was rebuilt after the big fire that swept the city and dotted with sculptures and pavilions, Mirogoj ulica vladimira nazora hall for balls and concerts, convent of St Claire and in 1731 but miraculously spared a painting of Virgin Mary – and is a serene, gorgeously landscaped park with neo- today the majestic palace take a peep at the turret so the gate became a chapel dedicated to the Mother of God, Renaissance arcades designed by Herman Bollé. houses the Croatian called the Priest’s Tower at with flickering candle lights and plaques of gratitude covering History Museum, with 9 st mark’s square the northern end, built in the walls. -

Zagrebački Holding D.O.O

PROFIL TVRTKE / COMPANY PROFILE SADRŽAJ / CONTENT 2 3 UVOD 4 INTRODUCTION POVIJEST 8 HISTORY VIZIJA I MISIJA 12 VISION AND MISSION ORGANIZACIJSKA STRUKTURA 14 ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE ZAPOSLENICI 16 EMPLOYEES PODRUŽNICE 18 BRANCHES TRGOVAČKA DRUŠTVA 54 COMMERCIAL COMPANIES ZAGREB HOLDING // COMPANY PROFILE USTANOVA 64 INSTITUTION ZAGREBAČKI HOLDING D.O.O. // PROFIL TVRTKE POSLOVATI ODGOVORNO 66 RESPONSIBLE BUSINESS UVOD / INTRODUCTION Zagrebački holding d.o.o. osnovan je 2005. godine prema Zagreb Holding was founded in 2005 pursuant to the Zakonu o trgovačkim društvima kao Gradsko komunalno Companies Act as the City Municipal Services Company gospodarstvo d.o.o., da bi 2007. promijenio naziv u Za- (Gradsko komunalno gospodarstvo), and in 2007 it changed grebački holding. U stopostotnom je vlas ništvu Grada its name to Zagreb Holding. It is completely owned by the City of Zagreb. Zagreba. It consists of 18 branches, which perform the work of the Sastoji se od 18 podružnica koje obavljaju djelatnosti ne- former city companies and it employs a total of 12,000 kadašnjih gradskih poduzeća, a ukupni broj zaposlenih je people. The Holding is also the owner of six commercial 4 oko 12 000. Holding je vlasnik i šest trgo vačkih društava 5 companies and one institution, with a further thousand te jedne ustanove s još oko tisuću zapo slenih. employees. Djelatnosti Društva grupirane su u tri poslovna po dručja: The work of the Company is divided into three areas of 1. komunalne djelatnosti business: 2. prometne djelatnosti 1. Municipal work 3. tržišne djelatnosti. 2. Transport Čistoća, Zagrebački digitalni grad, Gradska groblja, Trž- 3. Market activities nice Zagreb, Vodoopskrba i odvodnja, Zagrebačke ceste, Waste Disposal, Zagreb Digital City, City Graveyards, Zagreb Markets, Water Supply and Drainage, Zagreb Roads, City ZAGREB HOLDING // COMPANY PROFILE Zbrinjavanje gradskog otpada (ZGOS) i Zrinjevac podruž- ZAGREBAČKI HOLDING D.O.O. -

Mogućnosti Implementacije Novih Sadrţaja U Nastavu Likovne Umjetnosti – Interpretacija Suvremenih Grafita

SVEUĈILIŠTE U ZAGREBU FILOZOFSKI FAKULTET Odsjek za povijest umjetnosti Diplomski rad MOGUĆNOSTI IMPLEMENTACIJE NOVIH SADRŢAJA U NASTAVU LIKOVNE UMJETNOSTI – INTERPRETACIJA SUVREMENIH GRAFITA Hana Juranović Mentor: dr. sc. Jasmina Nestić, doc. Komentor: dr. sc. Frano Dulibić, red. prof. ZAGREB, 2019. Temeljna dokumentacijska kartica Sveuĉilište u Zagrebu Diplomski rad Filozofski fakultet Odsjek za povijest umjetnosti Diplomski studij MOGUĆNOSTI IMPLEMENTACIJE NOVIH SADRŢAJA U NASTAVU LIKOVNE UMJETNOSTI – INTERPRETACIJA SUVREMENIH GRAFITA The possibilities for implementing new contents in visual arts education – an interpretation of contemporary graffiti Hana Juranović U radu je predstavljena mogućnost implementacije suvremenih grafita i uliĉne umjetnosti kao novog sadrţaja u nastavi Likovne umjetnosti. Grafiti kao dio umjetnosti u javnom prostoru su fenomen prisutan na svim gradskim površinama te će se uĉenicima pobliţe predstaviti putem projektne nastave. Za projektnu nastavu je predviĊeno trajanje od tri tjedna. Tijekom nje će se uĉenici u prvome tjednu upoznati sa svjetskom grafiterskom scenom i njenim umjetnicima, dok će se u drugome tjednu upoznati s onom domaćom, toĉnije scenom zagrebaĉkih grafita. U trećemu tjednu uĉenici će se pobliţe upoznati s problematikom podruĉja grafita kao marginalnog dijela umjetnosti te u nju ulaze diskusijom. Kroz cijelo trajanje projektne nastave uĉenici će razvijati svoje kompetencije i vještine kritiĉkim promišljanjem u uĉioniĉkoj i terenskoj nastavi. U nastavi se takoĊer potiĉe samostalnost uĉenika, oni su glavni akteri debate putem koje se dotiĉu aktualnih pitanja na koja će pokušati odgovoriti kroz kvalitetnu argumentaciju i jasno izraţavanje stavova. Kontinuiranim radom na metodiĉkim vjeţbama uĉenici će njegovati kulturu ruke i vlastite kreativne sposobnosti koje će se izraziti i na kraju prezentirati kroz finalni projektni zadatak. Metodom samoevaluacije i koevaluacije uĉenici će razvijati smisao za odgovornost te vrednovati meĊusobnu zainteresiranost i kvalitetu aktivnosti. -

Zagreb Winter 2019-2020

Maps Events Restaurants Cafés Nightlife Sightseeing Shopping Zagreb Winter 2019-2020 COOL-TURE The best of culture and events this winter N°98 - complimentary copy zagreb.inyourpocket.com Contents ESSENTIAL CIT Y GUIDES Foreword 4 Zagorje Day Trip 51 A zesty editorial to unfold Beautiful countryside Cool-ture 6 Shopping 52 The best of culture and events this winter Priceless places and buys Restaurants 32 Arrival & Getting Around 60 We give you the bread ‘n’ butter of where to eat SOS! Have no fear, ZIYP is here Coffee & Cakes 43 Maps “How’s that sweet tooth?” Street Register 63 City Centre Map 64-65 Nightlife 46 City Map 66 Are you ready to party? Sightseeing 49 Discover what we‘ve uncovered Bowlers, Photo by Ivo Kirin, Prigorje Museum Archives facebook.com/ZagrebInYourPocket Winter 2019-2020 3 Foreword Winter is well and truly here and even though the days are shorter and the nights both longer and colder, there is plenty of room for optimism and cheer and we will give you a whole load of events and reasons to beg that receptionist back at the hotel/hostel to prolong your stay for another day or week! But the real season by far is Advent, the lead up to Christmas where Zagrebians come out in force and Publisher Plava Ponistra d.o.o., Zagreb devour mulled wine, grilled gourmet sausages, hot round ISSN 1333-2732 doughnuts, and many other culinary delights. And since Advent is in full swing, we have a resounding wrap up of Company Office & Accounts Višnja Arambašić what to do and see.