19Th Century Emigration from Cornwall As Experienced by the Wives ‘Left Behind’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Year 6 Term 3 Cornwall

Constantine’s Creative Curriculum Tresillian Class - Summer term Cornwall This term, children will be immersed in everything Cornish! Through studying our local area, children will learn about the mining heritage of our county. Children will also learn about Pip Staffieri, Europe’s first stand up surfer from Newquay and explore about how surfing became so popular in our county. Through geographical enquiry, children will discover the diverse features of Cornwall and be able to locate famous Cornish landmarks. A trip to Geevor Tin Mine will enable children to understand what life would have been like as a miner. Art will also be a large focus this term as we explore Cornwall’s most influential artists. Constantine Primary School Topic: Cornwall Y6 What I should already know: Vocabulary: Cornwall is a county in England in the South West Ordnance survey map – it creates up-to-date paper Cornwall is surrounded by coastline and digital maps Tourism is the main industry in Cornwall Aerial view – a viewpoint from great height Cornwall has a rich fishing and mining heritage Wheal (Vyvyan) meaning workplace Surfing is a popular sport in Cornwall Engine house building containing a steam engine Smelting the process in which tin metal is extracted from black tin By the end of this unit, I will: Industry – the companies and activities involved in Know the key events of the history of mining in the process of producing goods for sale Cornwall Industrial revolution – the transition to new Know the location of famous Cornish landmarks manufacturing processes Understand the impact that a significant Cornish Heritage – values, traditions, culture and artefacts figure has had on Cornwall handed down by previous generations Understand the location of Constantine parish in the Bal – a mine county, country and wider world Bal maiden – a female worker in the mining industry Be able to use OS maps to study a local area including Bonnet – a bal maiden’s traditional hat the Helford and Kenwyn rivers. -

Daily Report Thursday, 20 July 2017 CONTENTS

Daily Report Thursday, 20 July 2017 This report shows written answers and statements provided on 20 July 2017 and the information is correct at the time of publication (06:34 P.M., 20 July 2017). For the latest information on written questions and answers, ministerial corrections, and written statements, please visit: http://www.parliament.uk/writtenanswers/ CONTENTS ANSWERS 10 Social Tariffs: Torfaen 19 ATTORNEY GENERAL 10 Taxation: Electronic Hate Crime: Prosecutions 10 Government 19 BUSINESS, ENERGY AND Technology and Innovation INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY 10 Centres 20 Business: Broadband 10 UK Consumer Product Recall Review 20 Construction: Employment 11 Voluntary Work: Leave 21 Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy: CABINET OFFICE 21 Mass Media 11 Brexit 21 Department for Business, Elections: Subversion 21 Energy and Industrial Strategy: Electoral Register 22 Staff 11 Government Departments: Directors: Equality 12 Procurement 22 Domestic Appliances: Safety 13 Intimidation of Parliamentary Economic Growth: Candidates Review 22 Environment Protection 13 Living Wage: Jarrow 23 Electrical Safety: Testing 14 New Businesses: Newham 23 Fracking 14 Personal Income 23 Insolvency 14 Public Sector: Blaenau Gwent 24 Iron and Steel: Procurement 17 Public Sector: Cardiff Central 24 Mergers and Monopolies: Data Public Sector: Ogmore 24 Protection 17 Public Sector: Swansea East 24 Nuclear Power: Treaties 18 Public Sector: Torfaen 25 Offshore Industry: North Sea 18 Public Sector: Wrexham 25 Performing Arts 18 Young People: Cardiff Central -

Market Street, Hayle, TR27 4DZ £1,500,000 Freehold

• PLANNING APPROVAL FOR 70 HOMES Market Street, Hayle, TR27 4DZ • PA15/10513 DEVELOPMENT SITE FOR 70 HOMES IN THE POPULAR COASTAL TOWN OF HAYLE • SITE EXTENDS TO 3,600sqm * VIDEO TOUR AVAILABLE ON OUR WEBSITE * • HAYLE SURROUNDS A BEAUTIFUL ESTUARY ON THE EDGE OF ST IVES BAY IN WEST CORNWALL £1,500,000 Freehold SITE This is an excellent opportunity to acquire a 3600sqm development site with detailed Planning Permission for 70 new dwellings situated in the heart of West Cornwall's ever popular town of Hayle. Hayle is famed for its three miles of golden sands, Hayle is one of the most popular holiday locations in the South West. The modern parish shares boundaries with St Ives, approximately 3 miles to the west, and St Erth to the south, Gwinear and Gwithian in the east. A site of this magnitude in such an enviable location is seldom available, and as such is certainly an eye catching development opportunity. PA15/10513 Demolition of existing warehouse type building comprising 3,600 square metres of floorspace and the erection of a 70 unit residential development comprising:- 1 x 4 bedroom house. 2 x 2 bedroom houses. 10 x 1 bedroom flats and 57 x 2 bedroom flats. Revised and improved access road. Parking provision. Landscaping. Cycle and bin storage. Retention of existing 'Scoria' block retaining wall at the rear of the site. R & J Supplies, Copper Terrace, Copperhouse, Hayle, Cornwall TR27 4DZ for further information please contact 01736 754115. LOCATION Situated on the opposite side of St Ives Bay, Hayle is famed for its three miles of golden sand. -

O-TYPE VOWELS in CORNISH Dr Ken George

GEORGE 2013 2ovowels O-TYPE VOWELS IN CORNISH by Dr Ken George Cornish Language Board 1 A B S T R A C T Evidence from traditional Cornish texts and from place-names is used to trace the development of the two o-type vowels, /o/ and / ɔ/. Recent denials by Williams of the existence of two long o-type vowels are refuted. Further evidence shows a difference between /o/ and / ɔ/ when short, and by inference, when of mid-length. The significance of this for the spelling of the revived language is briefly discussed. 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 /ɔ/ and /o/ In George (1984), I showed that there were two o-type vowels in Middle Cornish (MidC), which will be denoted /o/ and / ɔ/. /o/, from Old Cornish (OldC) /ui/ and /ɔ/ from OldC / ɔ/ were separate phonemes. Support for their separateness, when followed by [s], [z], [ θ] and [ ð] appears in three different historical orthographies, in rhymes and in place-names. (The evidence in other phonetic environments, particularly when followed by nasal and liquid consonants, is weaker, and is reviewed below). My discovery has gained wide acceptance, but has been persistently attacked by Nicholas Williams. In Williams (2006), he devoted a whole chapter (31 pages) to the case of the long stressed vowels, concluding: “Middle Cornish never contained two separate long vowels /o ː/ and / ɔː/. 2. The distinction … between troes ‘foot’ and tros ‘noise’ is unjustified.” In this paper, the evidence for the two o-type vowels is reviewed in detail, and the reasons for Williams’ erroneous conclusion are examined. -

Parish Boundaries

Parishes affected by registered Common Land: May 2014 94 No. Name No. Name No. Name No. Name No. Name 1 Advent 65 Lansall os 129 St. Allen 169 St. Martin-in-Meneage 201 Trewen 54 2 A ltarnun 66 Lanteglos 130 St. Anthony-in-Meneage 170 St. Mellion 202 Truro 3 Antony 67 Launce lls 131 St. Austell 171 St. Merryn 203 Tywardreath and Par 4 Blisland 68 Launceston 132 St. Austell Bay 172 St. Mewan 204 Veryan 11 67 5 Boconnoc 69 Lawhitton Rural 133 St. Blaise 173 St. M ichael Caerhays 205 Wadebridge 6 Bodmi n 70 Lesnewth 134 St. Breock 174 St. Michael Penkevil 206 Warbstow 7 Botusfleming 71 Lewannick 135 St. Breward 175 St. Michael's Mount 207 Warleggan 84 8 Boyton 72 Lezant 136 St. Buryan 176 St. Minver Highlands 208 Week St. Mary 9 Breage 73 Linkinhorne 137 St. C leer 177 St. Minver Lowlands 209 Wendron 115 10 Broadoak 74 Liskeard 138 St. Clement 178 St. Neot 210 Werrington 211 208 100 11 Bude-Stratton 75 Looe 139 St. Clether 179 St. Newlyn East 211 Whitstone 151 12 Budock 76 Lostwithiel 140 St. Columb Major 180 St. Pinnock 212 Withiel 51 13 Callington 77 Ludgvan 141 St. Day 181 St. Sampson 213 Zennor 14 Ca lstock 78 Luxul yan 142 St. Dennis 182 St. Stephen-in-Brannel 160 101 8 206 99 15 Camborne 79 Mabe 143 St. Dominic 183 St. Stephens By Launceston Rural 70 196 16 Camel ford 80 Madron 144 St. Endellion 184 St. Teath 199 210 197 198 17 Card inham 81 Maker-wi th-Rame 145 St. -

A Sensory Guide to King Edward

Sensory experiences a sensory guide to Blackberries from the hedgerow, a pasty picnic. King Edward Mine Carn Brea monument, towering engine houses. A buzzards cry, the silence, imagine the constant hammering of the stamps. The granite blocks of the engine houses. Gorse flowers, clean air. A tale of the Bal I used to leave Carwinnen at six o’clock in the morning. It was alright in the summer, but in the winter mornings I was afraid of the dark. When I “ got to Troon the children used to come along from Welcome to King Edward Mine Black Rock and Bolenowe. We used to lead hands King Edward Mine has been an important part of Cornish and sing to keep“ our spirits up. Sometimes when Mining history for the last 200 years. It began as a copper mine, we got to the Bal the water was frozen over. I have then it turned to tin. Many men, women and children from cried scores of times with wonders in my fingers the surrounding area would have walked to work here every and toes. day, undertaking hard physical work all day long to mine and process the ore from the ground into precious Cornish tin. A Dolcoath Bal Maiden 1870, Mrs Dalley. The site later became home to the Camborne School of Mines. This internationally renowned institution taught students from all around the world the ways of mining. These students then took the skills learnt here in Cornwall across the globe. www.sensorytrust.org.uk The landscape would have Working life Recollections of the Red River Tin looked like this.. -

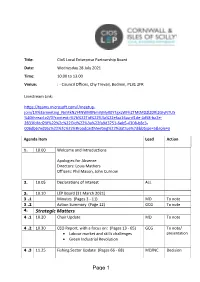

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Cornwall and Isles of Scilly Local

Title: CIoS Local Enterprise Partnership Board Date: Wednesday 28 July 2021 Time: 10.00 to 13.00 Venue: : - Council Offices, Chy Trevail, Bodmin, PL31 2FR Livestream Link: https://teams.microsoft.com/l/meetup- join/19%3ameeting_NmFkNzY4NWMtNmVjMy00YTgxLWFhZTMtMDZlZDRlZGIyNTU5 %40thread.v2/0?context=%7b%22Tid%22%3a%22efaa16aa-d1de-4d58-ba2e- 2833fdfdd29f%22%2c%22Oid%22%3a%22fa9d3751-6eb5-4308-b8c3- 006db67ed9ac%22%2c%22IsBroadcastMeeting%22%3atrue%7d&btype=a&role=a Agenda Item Lead Action 1. 10.00 Welcome and Introductions Apologies for Absence Directors: Louis Mathers Officers: Phil Mason, John Curnow 2. 10.05 Declarations of Interest ALL 3. 10.10 LEP Board (31 March 2021) 3 .1 Minutes (Pages 3 - 11) MD To note 3 .2 Action Summary (Page 12) GCG To note 4. Strategic Matters 4 .1 10.20 Chair Update MD To note 4 .2 10.30 CEO Report, with a focus on: (Pages 13 - 65) GCG To note/ Labour market and skills challenges presentation Green Industrial Revolution 4 .3 11.25 Fishing Sector Update (Pages 66 - 68) MD/NC Decision Page 1 4 .4 11.50 Nominations Committee Update (Pages 69 - GCG Decision 122) 4 .5 12.15 Audit & Assurance Committee Update (Pages GCG Decision 123 - 198) 4 .6 12.25 Enterprise Zones Board Update (Pages 199 - SJ/GCG To note 202) 4 .7 12.35 Any other business 5. Exclusion of Press and Public 5 .1 12.40 Investment & Oversight Panel Update (Pages MD/GCG To note 203 - 206) 5 .2 12.50 Any other confidential business ALL Page 2 Agenda No. 3.1 Information Classification: CONTROLLED CORNWALL AND ISLES OF SCILLY LOCAL ENTERPRISE PARTNERSHIP MINUTES of a Meeting of the Cornwall and Isles of Scilly Local Enterprise Partnership held in the Online - Virtual Meeting on Wednesday 31 March 2021 commencing at 10.00 am. -

St Hilary Neighbourhood Development Plan

St Hilary Neighbourhood Development Plan Survey review & feedback Amy Walker, CRCC St Hilary Parish Neighbourhood Plan – Survey Feedback St Hilary Parish Council applied for designation to undertake a Neighbourhood Plan in December 2015. The Neighbourhood Plan community questionnaire was distributed to all households in March 2017. All returned questionnaires were delivered to CRCC in July and input to Survey Monkey in August. The main findings from the questionnaire are identified below, followed by full survey responses, for further consideration by the group in order to progress the plan. Questionnaire responses: 1. a) Which area of the parish do you live in, or closest to? St Hilary Churchtown 15 St Hilary Institute 16 Relubbus 14 Halamanning 12 Colenso 7 Prussia Cove 9 Rosudgeon 11 Millpool 3 Long Lanes 3 Plen an Gwarry 9 Other: 7 - Gwallon 3 - Belvedene Lane 1 - Lukes Lane 1 Based on 2011 census details, St Hilary Parish has a population of 821, with 361 residential properties. A total of 109 responses were received, representing approximately 30% of households. 1 . b) Is this your primary place of residence i.e. your main home? 108 respondents indicated St Hilary Parish was their primary place of residence. Cornwall Council data from 2013 identify 17 second homes within the Parish, not including any holiday let properties. 2. Age Range (Please state number in your household) St Hilary & St Erth Parishes Age Respondents (Local Insight Profile – Cornwall Council 2017) Under 5 9 5.6% 122 5.3% 5 – 10 7 4.3% 126 5.4% 11 – 18 6 3.7% 241 10.4% 19 – 25 9 5.6% 102 4.4% 26 – 45 25 15.4% 433 18.8% 46 – 65 45 27.8% 730 31.8% 66 – 74 42 25.9% 341 14.8% 75 + 19 11.7% 202 8.8% Total 162 100.00% 2297 100.00% * Due to changes in reporting on data at Parish level, St Hilary Parish profile is now reported combined with St Erth. -

Natural Phonetic Tendencies and Social Meaning: Exploring the Allophonic Raising Split of PRICE and MOUTH on the Isles of Scilly

This is a repository copy of Natural phonetic tendencies and social meaning: Exploring the allophonic raising split of PRICE and MOUTH on the Isles of Scilly. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/133952/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Moore, E.F. and Carter, P. (2018) Natural phonetic tendencies and social meaning: Exploring the allophonic raising split of PRICE and MOUTH on the Isles of Scilly. Language Variation and Change, 30 (3). pp. 337-360. ISSN 0954-3945 https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954394518000157 This article has been published in a revised form in Language Variation and Change [https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954394518000157]. This version is free to view and download for private research and study only. Not for re-distribution, re-sale or use in derivative works. © Cambridge University Press. Reuse This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (CC BY-NC-ND) licence. This licence only allows you to download this work and share it with others as long as you credit the authors, but you can’t change the article in any way or use it commercially. More information and the full terms of the licence here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Title: Natural phonetic tendencies -

Truro 1961 Repairs BLISLAND St

Locality Church Name Parish County Diocese Date Grant reason BALDHU St. Michael & All Angels BALDHU Cornwall Truro 1961 Repairs BLISLAND St. Pratt BLISLAND Cornwall Truro 1894-1895 Reseating/Repairs BOCONNOC Parish Church BOCONNOC Cornwall Truro 1934-1936 Repairs BOSCASTLE St. James MINSTER Cornwall Truro 1899 New Church BRADDOCK St. Mary BRADDOCK Cornwall Truro 1926-1927 Repairs BREA Mission Church CAMBORNE, All Saints, Tuckingmill Cornwall Truro 1888 New Church BROADWOOD-WIDGER Mission Church,Ivyhouse BROADWOOD-WIDGER Devon Truro 1897 New Church BUCKSHEAD Mission Church TRURO, St. Clement Cornwall Truro 1926 Repairs BUDOCK RURAL Mission Church, Glasney BUDOCK RURAL, St. Budoc Cornwall Truro 1908 New Church BUDOCK RURAL St. Budoc BUDOCK RURAL, St. Budoc Cornwall Truro 1954-1955 Repairs CALLINGTON St. Mary the Virgin CALLINGTON Cornwall Truro 1879-1882 Enlargement CAMBORNE St. Meriadoc CAMBORNE, St. Meriadoc Cornwall Truro 1878-1879 Enlargement CAMBORNE Mission Church CAMBORNE, St. Meriadoc Cornwall Truro 1883-1885 New Church CAMELFORD St. Thomas of Canterbury LANTEGLOS BY CAMELFORD Cornwall Truro 1931-1938 New Church CARBIS BAY St. Anta & All Saints CARBIS BAY Cornwall Truro 1965-1969 Enlargement CARDINHAM St. Meubred CARDINHAM Cornwall Truro 1896 Repairs CARDINHAM St. Meubred CARDINHAM Cornwall Truro 1907-1908 Reseating/Repairs CARDINHAM St. Meubred CARDINHAM Cornwall Truro 1943 Repairs CARHARRACK Mission Church GWENNAP Cornwall Truro 1882 New Church CARNMENELLIS Holy Trinity CARNMENELLIS Cornwall Truro 1921 Repairs CHACEWATER St. Paul CHACEWATER Cornwall Truro 1891-1893 Rebuild COLAN St. Colan COLAN Cornwall Truro 1884-1885 Reseating/Repairs CONSTANTINE St. Constantine CONSTANTINE Cornwall Truro 1876-1879 Repairs CORNELLY St. Cornelius CORNELLY Cornwall Truro 1900-1901 Reseating/Repairs CRANTOCK RURAL St. -

Cornwall. Pub 1445

TRADES DIRECTORY.] CORNWALL. PUB 1445 . Barley Sheaf, Mrs. Mary Hawken, Lower Bore st. Bodmin Commercial hotel,John Wills,Dowugate,Linkiuhorne,Liskrd Barley Sheaf, Mrs. Elizabeth Hill, Church street, Liskeard Commercial hotel & posting house, Abraham Bond, Gunnis~ Barley Sheaf inn, Fred Liddicoat, Union square, St. Columb lake, Tavistock Major R.S.O Commercial hotel & posting establishment (Herbert Henry Barley Sheaf hotel, Mrs. Elizh. E. Reed, Old Bridge st. Truro Hoare, proprietor), Grampound Road Barley Sheaf, William Richards, Gorran, St. Austell Commercial hotel, family, commercial & posting house, Basset Arms, William Laity, Basset road, Camborne William Alfred Holloway, Porthleven, Helston Basset Arms, Solomon Rogers, Pool, Carn Brea R.S. 0 Commercial hotel, family, commercial & posting, Richard Basset Arms, Charles Wills, Portreath, Redruth Lobb. South quay, Padstow R.S.O Bay Tree, Mrs. Elizabeth Rowland, Stratton R.S.O Cornish Arms, Thomas Butler, Crockwell street, Bodmin .Bennett's Arms, Charles Barriball, Lawhitton, Launceston Cornish Arms, Jarues Collins, Wadebridge R.S.O Bell inn, William Ca·rne, Meneage street, Helston Cornish Arms, Mrs. Elizh. Eddy, Market Jew st. Penzance Bell inn, Daniel Marshall, Tower street, Launceston Cornish Arms, Jakeh Glasson, Trelyon, St. Ives R.S.O Bell commercial hotel & posting house, Mrs. Elizabeth Cornish Arms, Nicholas Hawken, Pendoggett, St. Kew, Sargent, Church street, Li.skeard Wadebridge R.S.O Bideford inn, Lewis Butler, l:ltratton R.S. 0 Cornish Arms, William LObb, St. Tudy R.S.O Black Horse, Richard Andrew, Kenwyn street, Truro CornishArms,Mrs.M.A. Lucas,St. Dominick,St. MellionR. S. 0 BliBland inn, Mrs. R. Williams, Church town,Blislaud,Bodmin Cornish Arms, Rd. -

ACTION NOTES Camborne Pool Illogan Redruth and Mining Villages

Information Classification: CONFIDENTIAL Notes Meeting Title: Camborne Pool Illogan Redruth and Mining Villages Community Network Meeting Date: 13 April 2021 Time: 5.45pm-7pm Location: Microsoft Teams Meeting Chaired by: Ian Thomas CC Present Title/ Representing Cllr David Atherfold Cornwall Councillor (Camborne Treslothan) Cllr Stephen Barnes Cornwall Councillor (Redruth North) Cllr Philip Desmonde Cornwall Councillor (Pool and Tehidy) Cllr Joyce Duffin Cornwall Councillor (Mount Hawke and Portreath) Cllr David Ekinsmyth CC Cornwall Councillor (Illogan) Cllr Barbara Ellenbroek CC Cornwall Councillor (Redruth Central) Cllr Ian Thomas CC (Chairman of CNP) Cornwall Councillor (Redruth South) Cllr Mary Anson Lanner Parish Council Cllr Chris Bell St Day Parish Council Cllr Valerie Chown Carharrack Parish Council Cllr Bettina Holland Carharrack Parish Council Cllr Rob Knill MVRG representative Cllr Cathy Page Redruth Town Council Cllr Deborah Reeve Redruth Town Council Cllr David Squire Lanner Parish Council Cllr Ian Stewart Portreath Parish Council Cllr Richard Williams Gwennap Parish Council Cllr Danielle Wills Carn Brea Parish Council Tamsin Mallett Kresen Kernow Claire Meakin Pool Academy Brian Piper Stithians Energy Group Anne Rowe Red Cross Lisa Stratton Reed in Partnership, Partnership Manager Allister Young Coastline Housing Cornwall Council Officers & Speakers Samantha Alexander Cornwall Council, Locality Manager, Kerrier Elisabeth Allcorn Cornwall Council, Communities Support Assistant Brian Barber Redruth Rotary Charlotte Caldwell Cornwall Council, Community Link Officer Ashley Wood Mining Villages Regeneration Group Apologies for absence: Dave Ager, Olly Bayliss, Helen Charlesworth-May, Eugene Clemence, Jeff Collins CC, Nicki Finn, Cllr Graham Ford, Rose Hitchens-Todd, Rob Nolan CC, Paul White CC, Fiona Wootton Information Classification: CONFIDENTIAL Notes: Item Key/ Action Points Action by 1 Welcome, introductions and apologies Councillor Ian Thomas welcomed everyone to the meeting.