The Causes of Revolution: a Case Study of Iranian Revolution of 1978-79 Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tracing the Role of Technology in Iranian Politics: from the Islamic Revolution of 1979 to the Presidential Election of 2009

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 21, Issue 4, Ver. 7 (Apr. 2016) PP 06-16 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Tracing the Role of Technology in Iranian Politics: From the Islamic Revolution of 1979 to the Presidential Election of 2009 Dr. Farid M.S Al-Salim History Program . Department of Humanities . College of Arts and Sciences. Qatar University P.O Box 2713 Doha, Qatar Abstract: This paper will attempt to examine the question: Given the advances in technology, why did the 2009 election protest movement fail to accomplish any of their goals while the participations of the 1979 Revolution were able to succeed in accomplishing their expressed objective? This question will provide a simplified test to a common tenant of those that support the use of technology as a means of bringing about regime change: that advances in communication technology are diffusing power away from governments and toward individual citizens and non-state actors. In order to answer this question this paper will examine the role of technology as an enabling factor in both the 1979 revolution and 2009 election protests. A brief historical context of the 1979 and 2009 conflicts will be provided, followed by a short history about the use of the Internet in Iran and finally the concluding remarks. Shah Muhammad Reza Pahlavi was said to be “The Shah-in-Shah” or the King of Kings.1 The head of the Iranian government, son of Reza Shah and architect of the White Revolution, Shah Muhammad Reza Pahlavi would also be the final ruling monarch of Iran. -

Islamic Education in Malaysia

Islamic Education in Malaysia RSIS Monograph No. 18 Ahmad Fauzi Abdul Hamid i i RSIS MONOGRAPH NO. 18 ISLAMIC EDUCATION IN MALAYSIA Ahmad Fauzi Abdul Hamid S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies i Copyright © 2010 Ahmad Fauzi Abdul Hamid Published by S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies Nanyang Technological University South Spine, S4, Level B4, Nanyang Avenue Singapore 639798 Telephone: 6790 6982 Fax: 6793 2991 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.idss.edu.sg First published in 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies. Body text set in 11/14 point Warnock Pro Produced by BOOKSMITH ([email protected]) ISBN 978-981-08-5952-7 ii CONTENTS 1 Introduction 1 2 Islamic Education 7 3 Introductory Framework and Concepts 7 4 Islamic Education in Malaysia: 13 The Pre-independence Era 5 Islamic Education in Malaysia: 25 The Independence and Post-Independence Era 6 The Contemporary Setting: Which Islamic 44 Education in Malaysia? 7 The Darul Arqam—Rufaqa’—Global Ikhwan 57 Alternative 8 Concluding Analysis 73 Appendixes 80 Bibliography 86 iii The RSIS/IDSS Monograph Series Monograph No. Title 1 Neither Friend Nor Foe Myanmar’s Relations with Thailand since 1988 2 China’s Strategic Engagement with the New ASEAN 3 Beyond Vulnerability? Water in Singapore-Malaysia Relations 4 A New Agenda for the ASEAN Regional Forum 5 The South China Sea Dispute in Philippine Foreign Policy Problems, Challenges and Prospects 6 The OSCE and Co-operative Security in Europe Lessons for Asia 7 Betwixt and Between Southeast Asian Strategic Relations with the U.S. -

Wujud Dan Tajalli Allah

36 35 PEMIKIRAN YUSUF QARDHAWI TENTANG ISLAM DAN DEMOKRASI A. Rusdiana Fakulas Tarbiyah dan Keguruan UIN Bandung ABSTRACT This study discusses Islamic Thinking and Democracy Yusuf Qoedhawi; through descriptive- analytical, the focus of this study looks at how the thinking is. It is known that the essence of democracy according to Yusuf Qardhawi is: "the people who choose the people who will govern and organize their problems, should not be forced upon those rulers whom they do not like or the regimes they hate.” The truth is that they are given the right to correct the authorities if they are wrong, given the right to revoke and replace them if they deviate, they are not allowed to be forced to follow various economic, social and political systems they neither know nor like. If some of them refuse, they should not be tortured, persecuted, and killed. "Democracy will provide some form and practical way in the life of the nation and the state.” Therefore, the study of the historical reflection of Yusuf Qardhawi is very urgent and strategic to do. Discussion begins with the life history, the works of Yusuf Qardhawi, and ends the style of thought and the basis of his argument. Keywords: participation, equity, understanding, supervision, and coverage. PENDAHULUAN universitas terkemuka di Barat. Sejak etelah runtuhnya Kekhalifahan Islam itulah banayk cendikiawan-cendikiawan Sterakhir yaitu Turki Utsmani, poros Muslim yang mempelajari ilmu kekuatan dunia berubah drastis. Barat pengetahuan dari Barat, salah satunya mulai menguasai dunia dengan adalah ideologi demokrasi. hegemoninya yang mencakup berbagai Demokrasi adalah pemerintahan bidang, baik bidang sosial, budaya, oleh rakyat, dari rakyat, untuk rakyat. -

Khomeinism, the Islamic Revolution and Anti Americanism

Khomeinism, the Islamic Revolution and Anti Americanism Mohammad Rezaie Yazdi A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham For the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Political Science and International Studies University of Birmingham March 2016 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract The 1979 Islamic Revolution of Iran was based and formed upon the concept of Khomeinism, the religious, political, and social ideas of Ayatullah Ruhollah Khomeini. While the Iranian revolution was carried out with the slogans of independence, freedom, and Islamic Republic, Khomeini's framework gave it a specific impetus for the unity of people, religious culture, and leadership. Khomeinism was not just an effort, on a religious basis, to alter a national system. It included and was dependent upon the projection of a clash beyond a “national” struggle, including was a clash of ideology with that associated with the United States. Analysing the Iran-US relationship over the past century and Khomeini’s interpretation of it, this thesis attempts to show how the Ayatullah projected "America" versus Iranian national freedom and religious pride. -

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS Studia Iranica Upsaliensia 28

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS Studia Iranica Upsaliensia 28 Traces of Time The Image of the Islamic Revolution, the Hero and Martyrdom in Persian Novels Written in Iran and in Exile Behrooz Sheyda ABSTRACT Sheyda, B. 2016. Traces of Time. The Image of the Islamic Revolution, the Hero and Martyrdom in Persian Novels Written in Iran and in Exile. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. Studia Iranica Upsaliensia 28. 196 pp. Uppsala. ISBN 978-91-554-9577-0 The present study explores the image of the Islamic Revolution, the concept of the hero, and the concept of martyrdom as depicted in ten post-Revolutionary Persian novels written and published in Iran compared with ten post-Revolutionary Persian novels written and published in exile. The method is based on a comparative analysis of these two categories of novels. Roland Barthes’s structuralism will be used as the theoretical tool for the analysis of the novels. The comparative analysis of the two groups of novels will be carried out within the framework of Foucault’s theory of discourse. Since its emergence, the Persian novel has been a scene for the dialogue between the five main discourses in the history of Iran since the Constitutional Revolution; this dialogue, in turn, has taken place within the larger framework of the dialogue between modernity and traditionalism. The main conclusion to be drawn from the present study is that the establishment of the Islamic Republic has merely altered the makeup of the scene, while the primary dialogue between modernity and traditionalism continues unabated. This dialogue can be heard in the way the Islamic Republic, the hero, and martyrdom are portrayed in the twenty post-Revolutionary novels in this study. -

HUMAN SPIRITUALITY PHASES in SUFISM the Study of Abu> Nas}R Al

Teosofia: Indonesian Journal of Islamic Mysticism, Volume 6, Number 1, 2017 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21580/tos.v6i1.1699Human Spirituality Phases in Sufism… HUMAN SPIRITUALITY PHASES IN SUFISM The Study of Abu> Nas}r Al-Sarra>j’s Thought in The Book of al-Luma' Ayis Mukholik Ph.D Candidate, Pascasarjana Universitas Indonesia [email protected] Abstract This study discusses the phases that human beings must go through to achieve a noble degree in the sight of God. In Sufism, this topic is known as maqa>ma>t and ah}wa>l. Maqa>ma>t is the spiritual position, that is, the existence of a person in the way of Allah by trying to practice the deeds to be closer to Allah. While ahwa>l is a condition or spiritual circumstance within heart bestowed by God because of the intensity of the dh}ikr (remembering God). To reach the highest level (ma'rifatullah), it can not be reached in a way that is easy and short time. Man must try to empty himself from sin and fill it with good deeds. For only with a holy soul, God gives much of His knowledge. This paper describes and analyze the stages of human spirituality in the book of a classic Sufi figure, Abu Nas}r Al-Sarra>j. Through inner experience, Sarraj formulated the concept of being close to God. This thought is based on the social conditions of society at that time concerning with material matters rather than spiritual ones. Therefore, the question is how the spiritual phases should be achieved by Al-Sarra>j? To answer this question, the researcher uses a qualitative method by examining the text and analyzing it to find the sequences of phases. -

1 UCSD, Department of History HINE 126 – Iranian Revolution In

1 UCSD, Department of History HINE 126 – Iranian Revolution in Historical Perspective Winter Quarter 2006 Professor: Dr. Ali Gheissari E-mail: [email protected] Office: HSS 4086B, Phone: (858) 534 3541 Office Hrs: Tuesday / Thursday 2:45-3:20 PM Class: Tuesday / Thursday 3:30-4:50 PM, Peterson Hall 103 Tests: Midterm: Thursday, February 16, 2006, 3:30-4:50 PM, in-class. Final: Friday, March 24, 2006, 3:00-6:00 PM, in-class. Iranian Revolution in Historical Perspective This course will study the Iranian revolution of 1979 in its historical context, and will examine major aspects of the political and social history of modern Iran. It will include reformist ideas in the 19th century Qajar society, the Constitutional movement of the early 20th century, nationalism, formation and development of the Pahlavi state, anatomy of the 1979 revolution, and a survey of the Islamic Republic. Further attention will be given to certain political, social, and intellectual themes in 20th century Iran and their impact on the revolution, as well as discussions on the reception of (and response to) Western ideas in diverse areas such as political ideologies, legal theory, and ethics. Ultimately focus will be given to major currents after the revolution, such as debates on democracy and electoral politics, factionalism, reform movement, and conservative consolidation. Evaluation and Grading: There will be two tests: one midterm (35 points) and a final (65 points). Both tests will consist of a mixture of short and long Essays, based on two Study Guides relating to each half of the course. Students are advised to pay utmost attention in fulfilling these Study Guides. -

Khomeini's Theory of Islamic State and the Making of the Iranian

Khomeini's Theory of Islamic State and the Making of the Iranian Revolution 1 Mehdi Shadmehr2 1I wish to thank Hassan Ansari, Charles Cameron, Jose Cheibub, Amaney Jamal, Ali Kadivar, Mehran Kamrava, Charles Kurzman, Paulina Marek, Charles Ragin, Kris Ramsay and seminar par- ticipants at the University of Rochester and the University of South Carolina, and MPSA Conference for helpful suggestions and comments. 2Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton. E-mail: [email protected]. Phone: (305) 747-5896. Abstract The Iranian Revolution is one of the most influential events of the late twentieth century, with far-reaching consequences that still echo through the rise of Islamic state. Drawing from both primary (interviews, autobiographies, documents, and data) and secondary sources, the paper shows that Khomeini's the doctrine of the Guardianship of the Jurist played a decisive role in the making of the Iranian Revolution by changing the goals and strategies of the religious opposition from reforming government policies to establishing an Islamic state. Khomeini's doctrine was first published in 1970 in his treatise, Islamic State. The paper argues that Khomeini's ideological innovation can account for the sharp contrast between the outcomes of widespread protests in the early 1960s and the late 1970s: they both shook the Pahlavi regime, but the former protests dissipated, while the latter culminated in the Iranian Revolution. Expanding the scope beyond Iran and Islam, the paper explores the role of ideological innovations in the Russian and American Revolutions, and discusses the potentially critical role of ideological innovations in democracy movements in Islamic countries. The revolution was in the minds and hearts of the people; a change in their religious sentiments, of their duties and obligations.. -

The Teachings of Sufism in the Suluk Pesisiran

The Teachings of Sufism in the Suluk Pesisiran Mohamad Zaelani¹, Zuriyati², Saifur Rohman2 ¹Doctoral Program of Language Education, Postgraduate, Universitas Negeri Jakarta, Indonesia 2Faculty of Language and Art, Universitas Negeri Jakarta, Jakarta, Indonesia Keywords: Sufism, suluk literature, Suluk Pesisiran, mystical teaching Abstract: Islam developed in Java, since the beginning, Sufism-style Islam. The world of Sufism among them is expressed through literary works. In the history of Javanese literature, the problem of Sufism is expressed in the form of suluk literature. Suluk literature was pioneered by one of Walisanga's members, namely Sunan Bonang at the end of the 15th century. This article focuses on the study of Sufism in one of Javanese suluk literary works, Suluk Pesisiran. The purpose of writing is to analyze Sufism in Suluk Pesisiran. The method used for this study is hermeneutics. The results of this study are in the form of an analysis of the meaning of mysticism values in the Suluk Pesisiran. From the results of these studies, it can be concluded that Suluk Pesisiran does have a close relationship with the teachings of Sufism, especially the moral teachings taken from the mystical teachings of Islam. 1 INTRODUCTION a literary tradition, there was a kind of view that Javanese society is a society that has a distinctive The presence of Islam in the archipelago --not only in mystical style (Ricklefs, 2013: 22). Because of the Java-- has influenced various joints of life. Not spared tendency of the people believe of mysticism, the from the influence of Islam, including in the field of attendance of Sufism-style of Islam which initially as literature. -

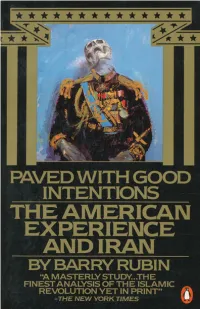

Paved-With-Good-Intentions-Final.Pdf

Paved with Good Intentions PENGUIN BOOKS PAVED WITH GOOD INTENTIONS Barry Rubin is a specialist on American foreign policy and on Middle East politics. He is a Fellow at George town University’s Center for Strategic and International Studies. PAVED WITH GOOD INTENTIONS The American Experience and Iran BARRY RUBIN PENGUIN BOOKS PENGUIN BOOKS Published by the Penguin Group Viking Penguin Inc., 40 West 23rd Street, New York, New York 10010, U.S.A. Penguin Books Ltd, 27 Wrights Lane, London W8 5TZ, England Penguin Books Australia Ltd, Ringwood, Victoria, Australia Penguin Books Canada Ltd, 2801 John Street, Markham, Ontario, Canada L3R 1B4 Penguin Books (N.Z.) Ltd, 182190 Wairau Road, Auckland 10, New Zealand Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England First published in Great Britain and the United States by Oxford University Press, Inc., 1980 Published in Penguin Books 1981 10 9 8 7 6 5 Copyright © Oxford University Press, Inc., 1980 All rights reserved LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING IN PUBLICATION DATA Rubin, Barry M. Paved with good intentions. Originally published: New York: Oxford University Press, 1980. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. United States—Foreign relations—Iran. 2. Iran— Foreign relations—United States. I. Title. E183.8.I55R83 1981 327.73055 814634 ISBN 0 14 00.5964 4 AACR2 Printed in the United States of America Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser Artificial sprites As by the strength of their illusion Shall draw him on to his confusion He shall spurn fate, scorn death and bear: His hopes ‘bove wisdom, grace and fear: And you all know security Is mortal’s chiefest enemy. -

Mohammad Reza Shah

RAHAVARD, Publishes Peer Reviewed Scholarly Articles in the field of Persian Studies: (Literature, History, Politics, Culture, Social & Economics). Submit your articles to Sholeh Shams by email: [email protected] or mail to:Rahavard 11728 Wilshire Blvd. #B607, La, CA. 90025 In 2017 EBSCO Discovery & Knowledge Services Co. providing scholars, researchers, & university libraries with credible sources of research & database, ANNOUNCED RAHAVARD A Scholarly Publication. Since then they have included articles & researches of this journal in their database available to all researchers & those interested to learn more about Iran. https://www.ebsco.com/products/research-databases/ultimate-databases. RAHAVARD Issues 132/133 Fall 2020/Winter 2021 2853$67,163,5(6285)8785( A Quarterly Bilingual Journal of Persian Studies available (in Print & Digital) Founded by Hassan Shahbaz in Los Angeles. Shahbaz passed away on May 7th, 2006. Seventy nine issues of Rahavard, were printed during his life in diaspora. With the support & advise of Professor Ehsan Yarshater, an Advisory Commit- tee was formed & Rahavard publishing continued without interuption. INDEPENDENT: Rahavard is an independent journal entirely supported by its Subscribers dues, advertisers & contributions from its readers, & followers who constitute the elite of the Iranians living in diaspora. GOAL: To empower our young generation with the richness of their Persian Heritage, keep them informed of the accurate unbiased history of the ex- traordinary people to whom they belong, as they gain mighty wisdom from a western system that embraces them in the aftermath of the revolution & infuses them with the knowledge & ideals to inspire them. OBJECTIVE: Is to bring Rahavard to the attention & interest of the younger generation of Iranians & the global readers educated, involved & civically mobile. -

Malfoozaat on Tasawwuf – Part One

Malfoozaat on Tasawwuf – Part One Of Hazrat Moulana Ashraf Ali Thanwi rahmatullahi alayh TASAWWUF – The Rooh (Soul) of the Deen TASAWWUF IS THE ROOH (SOUL) OF ISLAM Tasawwuf in reality is nothing but the ROOH of Islam. Islam consists of two fundamental parts, viz the external laws pertaining to Ibadat and. the internal state of beauty, concern, sincerity and perfection on which (he external laws are to be based. Thus Tasawwuf is an integral part of the Shariat of Islam. Any “tasawwuf” beyond the confines of the Shariat is not the Tasawwuf of the Qur’an and Hadith, but is a practice of fraud and deception. The Tasawwuf of ALL the great and illustrious Auliyaa operate within strict control of the Sunnat of our Nabi (sallallahu alayhi wasallam). A tasawwuf which is at variance with the Tasawwuf of Rasulullah (Sallallahu alayhi wasallam) is not Tasawwuf, but is some satanic concept designed to obtain the pleasure of shaitaan. The main purpose of Tasawwuf is to eliminate the bestial qualities in man and to supplant them with the noble and virtuous qualities of angels. In this direction, Tasawwuf employs the advices, exhortations, restrictions, prohibitions and remedies prescribed by the Qur’aan, Hadith and the authoritative and authentic Auliyaa of Islam. TWO EXTREMES WITH REGARD TO TASAWWUF (SUFISM) All the authentic principles of Tasawwuf are to be found in the Qur’an and Hadith. The notion that Tasawwuf is not in the Qur’an is erroneous. Errant Sufis as well as the superficial Ulama (Ulama-e-Khushk) entertain this notion. Both groups have misunderstood the Qur’an and Ahadith.