Joseph Benson's Initial Letter to John Wesley Concerning Spirit Baptism and Christian Perfection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collection on British Wesleyan Conference Presidents

Collection on British Wesleyan Conference Presidents A Guide to the Collection Overview Creator: Bridwell Library Title: Collection on British Wesleyan Conference Presidents Inclusive Dates: 1773-1950 Bulk Dates: 1790-1900 Abstract: Bridwell Library’s collection on British Wesleyan Conference Presidents comprises three scrapbook albums containing printed likenesses, biographical sketches, autographs, correspondence, and other documents relating to every British Wesleyan Conference president who served between 1790 (John Wesley) and 1905 (Charles H. Kelly). The collection represents the convergence of British Victorian interests in Methodistica and scrapbooking. To the original scrapbooks Bishop Frederick DeLand Leete added materials by and about ten additional twentieth-century Conference presidents. Accession No: BridArch 302.26 Extent: 6 boxes (3.5 linear feet) Language: Material is in English Repository Bridwell Library, Perkins School of Theology, Southern Methodist University Historical Note Conference Presidents in the Methodist Church of Great Britain serve one year terms in which they travel throughout Great Britain preaching and representing the denomination. Conference Presidents may serve non-consecutive additional terms. John Wesley personally presided over 1 Bridwell Library * Perkins School of Theology * Southern Methodist University annual conferences of ordained ministers and lay preachers serving in connection with the Methodist movement beginning in 1744. The office of President was instituted after Wesley’s death in 1791. Bridwell Library is the principal bibliographic resource at Southern Methodist University for the fields of theology and religious studies. Source: “The President and Vice-President,” Methodist Church of Great Britain website http://www.methodist.org.uk/who-we-are/structure/the-president-and-vice-president, accessed 07/23/2013 Scope and Contents of the Collection The engraved portraits, biographical notes, autographs, and letters in this collection represent every Conference president who served between 1790 and 1905. -

125 BOOK REVIEW J. Russell Frazier

Methodist History, 53:2 (January 2015) BOOK REVIEW J. Russell Frazier, True Christianity, The Doctrine of Dispensations in the Thought of John William Fletcher (1729-1785). Eugene, OR: Pickwick Publications, 2014. 320 pp. $31.50. J. Russell Frazier has offered a comprehensive interpretation of John William Fletcher’s doctrine of dispensations. He appropriately entitled it, True Christianity. Frazier has provided the context for understanding the thought of John Fletcher, highlighting that in his mature theological understanding he developed a soteriology corresponding to the history of salvation. Fletcher shows that the development of God’s revelation as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit generally reflects the personal history of salvation. In this reckoning, each individual believer progressively transitions from a general awareness of God to a more specific knowledge of God as Father and Creator revealed in the Old Testament. The believer then progresses to the knowledge of Jesus Christ, whose life is distinguished between his earthly ministry entailing his life, death, and resurrection (Easter) and the outpouring of his Holy Spirit upon the church (Pentecost). Frazier shows that the most problematic feature of Fletcher’s theology of dispensations is the soteriological use that he made between the early followers of Jesus (pre-Pentecostal believers) and Pentecostal believers. This theology of dispensations, as Frazier so rightly pointed out, has nothing in common with the dispensational theology of Darby or Schofield. As Frazier showed, Fletcher understood Jesus’ earthly life as a brief period of time which represented a development of faith which was “singular” (as Fletcher put it) to John the Baptist and the early disciples of Jesus. -

THE JOURNAL of the UNITED REFORMED CHURCH HISTORY

THE JOURNAL of the UNITED REFORMED CHURCH HISTORY SOCIETY (incorporating the Congregational Historical Society, founded in 1899, and the Presbyterian Historical Society of England founded in 1913.) . EDITOR; Dr. CLYDE BINFIELD, M.A., F.S.A. Volume 5 No.8 May 1996 CONTENTS Editorial and Notes .......................................... 438 Gordon Esslemont by Stephen Orchard, M.A., Ph.D. 439 The Origins of the Missionary Society by Stephen Orchard, M.A., Ph.D . ........................... 440 Manliness and Mission: Frank Lenwood and the London Missionary Society by Brian Stanley, M.A., Ph.D . .............................. 458 Training for Hoxton and Highbury: Walter Scott of Rothwell and his Pupils by Geoffrey F. Nuttall, F.B.A., M.A., D.D. ................... 477 Mr. Seymour and Dr. Reynolds by Edwin Welch, M.A., Ph.D., F.S.A. ....................... 483 The Presbyterians in Liverpool. Part 3: A Survey 1900-1918 by Alberta Jean Doodson, M.A., Ph.D . ....................... 489 Review Article: Only Connect by Stephen Orchard, M.A., Ph.D. 495 Review Article: Mission and Ecclesiology? Some Gales of Change by Brian Stanley, M.A., Ph.D . .............................. 499 Short Reviews by Daniel Jenkins and David M. Thompson 503 Some Contemporaries by Alan P.F. Sell, M.A., B.D., Ph.D . ......................... 505 437 438 EDITORIAL There is a story that when Mrs. Walter Peppercorn gave birth to her eldest child her brother expressed the hope that the little peppercorn would never get into a piclde. This so infuriated Mr. Peppercorn that he changed their name to Lenwood: or so his wife's family liked to believe. They were prosperous Sheffielders whom he greatly surprised by leaving a considerable fortune; he had proved to be their equal in business. -

Catalogue from Selecat

GENERAL AND REFERENCE 13 ) Osborn, G.; OUTLINES OF WESLEYAN BIBLIOGRAPHY OR A RECORD OF METHODIST 1 ) ; THE FIRST ANNUAL REPORT OF THE WESLEYAN LITERATURE FROM THE BEGINNING IN TWO PARTS; CHAPEL COMMITTEE 1855 [BOUND WITH] THE WCO; 1869; Osborn, G.Osborn, G. 220pp; Hardback, purple SECOND 1856 THE THIRD 1857 THE FOURTH 1858 cloth, spine faded & nicked. (M12441) £40 THE FIFTH 1859 THE SIXTH 1860 THE SEVENTH ANNUAL REPORT 1861; Hayman Brothers; 1855; pp; 14 ) Relly, James; UNION OR A TREATISE OF THE Rebound in black quarter leather. 7 parts bound together. Some CONSANGUINITY AND AFFINITY BETWEEN CHRIST dampstaining, mainly to the 3rd report. Illustrated with AND HIS CHURCH [WITH] THE SADDUCEE DETECTED lithographs. (M12201) £75 AND REFUTED IN REMARKS ON THE WORKS OF RICHARD COPPIN [1764]; Printed in the year; 1759; Relly, 2 ) ; THE METHODIST WHO'S WHO 1912; Charles H. JamesRelly, James 138+94+94pp; Full calf, gilt. Red leather Kelly; 1912; 255pp; Hardback, red cloth. (M12318) spine labels. Also bound in "The Trial of Spirits" 1762 without £20 title page. 3 works bound together, all rare. (M11994) 3 ) Batty, Margaret; STAGES IN THE DEVELOPMENT £100 AND CONTROL OF WESLEYAN LAY LEADERSHIP 1791- 15 ) Sangster, W.E.; METHODISM CAN BE BORN AGAIN; 1878; MPH; 1988; Batty, MargaretBatty, Margaret 275pp; Hodder & Stoughton; 1938; Sangster, W.E.Sangster, W.E. Paperback, covers dusty. Ring bound. (M12629) £10 128pp; Paperback. (M12490) £3 4 ) Cadogan, Claude L.; METHODISM: ITS IMPACT ON 16 ) Skewes, John Henry; A COMPLETE AND POPULAR CARIBBEAN PEOPLE A BICENTENNIAL LECTURE; St. DIGEST OF THE POLITY OF METHODISM EACH George's Grenada; 1986; Cadogan, Claude L.Cadogan, Claude SUBJECT ALPHABETICALLY ARRANGED; Elliot Stock; L. -

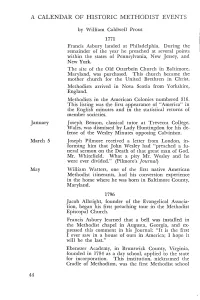

}\ Calendar of Historic Methodist Events

}\ CALENDAR OF HISTORIC METHODIST EVENTS by \IVilliam Caldwell Prout 1771 Francis Asbury landed at Philadelphia. During the remainder of the year he preached at several points within the states of Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and New York. The site of the Old Otterbein Church in Baltimore, Maryland, was purchased. This church became the mother church for the United Brethren in Christ. Methodists arrived in Nova Scotia from Yorkshire, England. Methodists in the American Colonies numbered 316. This listing was the first appearance of "America" in the English minutes and in the statistical returns of member societies. January Joseph Benson, classical tutor at Trevecca Col~ege, Wales, was dismissed by Lady Huntingdon for his de fense of the Wesley Minutes opposing Calvinism. March 5 Joseph Pilmore received a letter from London, in forming him that John Wesley had "preached a fu neral sermon on the Death of that great 11lan of God, Mr. Whitefield. What a pity Mr. '!\Tesley and he were ever divided." (Pilmore's ] oUTnal) May William Watters, one of the first native American Methodist itinerants, had his conversion experienc~ in the home where he was born in Baltimore County, Maryland. 1796 Jacob Albright, founder of the Evangelical Associa tion, began his first preaching tour in the Methodist Episcopal Church. Francis Asbury learned that a bell was installed in the Methodist chapel in Augusta, Georgia, and ex pressed this comment in his Journal: "It is the first I ever sa,,y in a house of ours in America; I hope it will be the last." Ebenezer Academy, in Brunswick County, Virginia, founded in 1784 as a day school, applied to the state for incorporation. -

MH-1996-April-Vickers.Pdf (7.931Mb)

ONE-MAN BAND: THOMAS COKE AND THE ORIGINS OF METHODIST MISSIONS I I I JOHN A. VICKERS I r When I became interested in Thomas Coke back in the 1950s, I was surprised how little seemed to be known about him~ and how much that was "known" proved to be wrong- or at the very least questionable. That was one thing which drew me to him. Another was the sheer variety of his commitments and act1ivities. To American Methodists, Coke is primarily Asbury's fellow bishop, who had a key role in the Christmas Conference in Baltimore and in the events that developed from it. To British Methodists (if indeed they have ever heard of him) Coke is first and last the "father of overseas missions" (and by that term we don't mean "converting the Americans''). And what is note worthy is this: his involvement in the formative days of the Methodist Episcopal Church and his pioneer role in overseas missions both date from the same year, 1784, and both occupied his time and energies concurrently during the years that followed. Coke was nothing if not a fireball of dedicated energy! It is as the missionary pioneer that Thomas Coke deserves our attention. For a seemingly definitive statement about the origin of British Methodist overseas missions we may turn to the Constitution of the Methodist Missionary Society (popularly known as the MMS, and now the Overseas Division). This was adopted in 1943, and states: "From the beginning of Methodist Overseas Missions at the Conference of 1786, the initiation, direction and support of Overseas Missions have been under taken by the Conference ..." and it goes on to claim: "The Methodist Missionary Society is none othet than the Methodist Church itself orga nised for Overseas Missions . -

Proceedings Wesley Historical Society

Proceedings OF THE Wesley Historical Society Editor: REv. WESLEY F. SWIFT VolomeXXvn ·1949-50 EDITORIAL E confidently anticipate that the List of Members of our Society-printed as. a supplement to this issue of the WProceedings by resolution of the Annual Meeting-will be perused with keen interest. Most of us have been working in the dark, without knowledge of the identity of our fellow-members; now at last we stand revealed to one another. The last List of Members was issued in 1936. What changes have taken place in our ranks since then! Many honoured brethren whose contributions enriched the early volumes of the Proceedings, some of them founder-members of the Society in 1893, have passed away. In numbers our Society has increased out of all knowledge. And what an interesting cross-section of the religious community the membership list is: peers and parsons, Presidents of the Con ference (nine out of a possible twelve) and probationers, super numeraries and students, Anglican clergymen and Methodist lay men-all of them deeply interested in the purposes for which the Society exists. And to what distant places of the earth does the Proceedings go! In Australia, New Zealand, America, South Africa, New Guinea, Japan, Sweden, Germany-and many other places-our members are to be found, all sharing the same interest in the story of our Church in all its branches. What would John Wesley say could he know of this enduring and world-wide interest in his life and work, and in the history of that Methodism which, though known by various names, owed its origin to his evangelical experience and zeal? * * * It is fitting that we should acknowledge the kind and gracious references to the Society and its Proceedings in the British Weekly of 15th September last. -

Collection on Methodism in the United Kingdom and Ireland

Collection on Methodism in the United Kingdom and Ireland A Guide to the Collection Overview Creator: Bridwell Library Title: Collection on Methodism in the United Kingdom and Ireland Inclusive Dates: 1740-1917 Bulk Dates: 1790-1890 Abstract: The letters, images, and other documents in this manuscript collection were created or received by Methodist leaders who lived in Great Britain, Ireland, Scotland, and Wales. Materials in the collection date from 1740 to 1917. The collection contains information about the lives of ministers, Wesleyan Conference presidents, and their correspondents. Accession No: BridArch 303.74 Extent: 3 boxes (3 linear feet) Language: Material is in English and Welsh Repository Bridwell Library, Perkins School of Theology, Southern Methodist University 1 Bridwell Library * Perkins School of Theology * Southern Methodist University Historical Note The British Isles are the homeland of Methodism, a religious and social holiness revival movement that began within the Church of England during the 1730s. John Wesley (1703- 1791), whose theological writings and organizational skills drove the movement, traced Methodism’s origins back to the Holy Club, a worship, study, and benevolent service group founded at Oxford University by his brother, Charles Wesley (1707-1788). In the summer of 1738 both John and Charles Wesley underwent dramatic conversions that resulted in a newfound religious enthusiasm that offended many fashionable churches in London. Excluded from their pulpits, John Wesley found a more receptive audience among the poor and laboring classes of England when he adopted field preaching at the urging of George Whitefield. John Wesley’s theology emphasized the work of the Holy Spirit in awakening a desire for God, assuring the Christian of God’s grace, and perfecting one’s love for God and neighbor. -

Joseph Benson's Initial Letter to John Wesley Concerning

Wesleyan Theological Journal, Vol. 48 No. 2, Fall 2013 JOSEPH BENSON’S INITIAL LETTER TO JOHN WESLEY CONCERNING SPIRIT BAPTISM AND CHRISTIAN PERFECTION by Randy L. Maddox and J. Russell Frazier John Wesley met in conference with the preachers in his connexion in August, 1770. The publication of the Minutes of this conference sparked a vigorous debate between Wesleyan and Calvinist Methodists. In a con - cluding section of these Minutes , Wesley and his associates reiterated the claim (originally made in 1744) that they had leaned too much toward Calvinism. To counter this, they insisted that a believer’s faithful response and works (in some sense) are a condition of final salvation. 1 The Calvin - ist Methodists (particularly those in connection with Lady Huntingdon) charged that these Minutes revealed the true colors of the Wesleyans—as enemies of grace. 2 Among those who sought to defend Wesley on this point, insisting that he grounded salvation firmly in grace, were Joseph Benson, currently the head master at Lady Huntingdon’s college in Trevecca, and John Fletcher, the college’s president. 3 Their alignment with Wesley led to Benson’s dismissal from the college in early January 1771, and Fletcher’s resignation that March. 4 The Benson-Fletcher Proposal Intriguingly, during this same period Benson and Fletcher began to champion a particular theological account of Christian perfection that 1The disputed section of the 1770 Conference Minutes is found at the end, in the answer to Question 28; see Richard Heitzenrater (ed.), The Works of John Wesley , Vol. 10 (Nashville: Abingdon, 2011), 392–394. -

The Life of Jabez Bunting

™ TMI HFI ©if? '/77 V,*- P. *«S4^i§^g n-uaJKs. 'The just and. lawful sovereignty over mens irnderstaiaahnsSTjy force of truth, rightly interpreted, is that which approacheth nearest to the sjuxihtu.de of the Divine rule ; 'THE LIFE JABEZ BUNTING, D.D., WITH NOTICES OF CONTEMPORARY PERSONS AND EVENTS. BY HIS SON, THOMAS PERCIVAL BUNTING. VOL. I. LONDON: LONGMAN, BROWN, GREEN, LONGMANS, & ROBERTS SOLD ALSO BY JOHN MASON, 66, PATERNOSTER ROW. EDINBURGH : ADAM AND CHARLES BLACK. 3859. LONDON: PUIKTKD BT VII.MAH MCH01.S, Jl, LONDON WALL. TO " THE PEOPLE CALLED METHODISTS," TO WHOM JABEZ BUNTING OWED SO MUCH, AND IN- WHOSE FELLOWSHIP AND SERVICE HE LIVED AND DIED, THIS RECORD OF HIS LIFE AND LABOURS IS GRATEFULLY AND AFFECTIONATELY DEDICATED. PREFACE. Toward the close of my Father's public life, it was his intention, frequently expressed, to look over his papers, and to destroy all which might furnish materials for his biography ; and, when casual allusions were made to the possibility of such a record, he often threatened that he would haunt the man who should attempt it. As age crept upon him, however, and he felt himself un- equal to heavy labour, other thoughts took pos- session of his mind. He gradually resigned himself to the conviction that the story of his life and labours must be told ; and, after much hesitation, he took steps accordingly. By his "Will, dated in 1852, he desired his two elder sons to examine all the papers, letters, and correspondence in his possession, at the time of his decease, and privately to destroy such portion thereof as, in their judgment, it might be expe- dient so to dispose of ; leaving his executors to M PKt exorcise their discretion as to what use should be made of the remainder. -

John Wesley's Journal

JEWS AND JUDAISM IN THE METHODIST COLLECTION, JOHN RYLANDS LIBRARY, MANCHESTER: LISTING Andrew Crome – 17 August 2016 Contents John Wesley’s Journal 1 Hymns 4 Wesley Family Papers 7 Fletcher-Tooth Letters 11 Joseph Benson Material 15 Hugh Bourne Material 16 Adam Clarke Material 18 Early Methodist Volume 23 Methodist Pamphlet Collection 24 John Wesley’s Journal All entries are taken from W. Reginald Ward and Richard P. Heitzenrater (eds), The Works of John Wesley Volumes 18-23: Journals and Diaries I-IV (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1988- 95). Monday 4 April 1737 Wesley records that he is beginning to learn Spanish in order to converse with “my Jewish parishioners”. These were lessons under the tutelage of Dr Samuel Nunez Ribeiro, a Portuguese Jew and medical doctor, who was responsible for ending an epidemic of Yellow Fever which was ravaging Savannah at that time . Wesley’s diaries (which contain short, often single word, records of his activities at various times in the day) record 34 visits to Nunez from June to August 1737.1 Thursday 7 July 1737 Wesley repents of a dispute he engaged in with Nunez on the messiah: “I was unawares engaged in a dispute with Dr. Nunez, a Jew, concerning the Messiah. For this I was afterward much grieved, lest the truth might suffer by my weak defence of it.”2 1 John C. English, “John Wesley and his ‘Jewish Parishioners’: Jewish-Christian Relationships in Savannah, Georgia, 1736-1737,” Methodist History 36 (July 1998), 220-227 2 Wesley still recalled his friendship with Nunez in the 1780s. -

The Normative Use of Pentecostal Sanctification in British And

Te Asbury Journal 71/2: 64-101 © 2016 Asbury Teological Seminary DOI: 10.7252/Journal.02.2016F.04 Laurence W. Wood The Normative Use of Pentecostal Sanctifcation in British and American Methodism Abstract This paper sets out to demonstrate that Pentecostal sanctifcation is a concept rooted in the theology of John Wesley, and that John Wesley and John Fletcher agreed theologically on this concept, contrary to other scholarly opinions frequently voiced on this subject. The view of Pentecostal sanctifcation was also held to be normative by early Methodists until the rise of liberal theology in the late 19th century, and this is evidenced by numerous historical references. The view that Pentecostal sanctifcation arose with either Phoebe Palmer in the Wesleyan-Holiness movement, or perhaps with John Fletcher as an outside voice from mainstream Methodism, is refuted and supporting evidence given. This paper was the second of two lectures of the Charles Elmer Cowman Lectures given at Seoul Theological Seminary from October 7-9, 2015 in Seoul, South Korea. Keywords: Pentecostal sanctifcation, holiness, John Wesley, John Fletcher, Methodism, Wesleyan-holiness Laurence W. Wood, Ph.D is the Frank Paul Morris Professor of Systematic Theology/Wesley Studies at Asbury Theological Seminary in Wilmore, KY 40390 64 Wood: The Normative Use of Pentecostal Sanctification 65 Introduction “Adhere closely to the ancient landmarks” [The Bishops’ Pastoral Address to the General Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church in 1852] 1 There is a misinformed rumor circulating among some Wesley scholars that Pentecostal sanctifcation was not a common interpretation in early Methodism, but rather it lay dormant in the writings of John Fletcher and only resurfaced into a full blown theology of the baptism with the Spirit with Phoebe Palmer and the Wesleyan-holiness movement in the second half of the 19th century.