Sea of Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Behind the Scenes: Uncovering Violence, Gender, and Powerful Pedagogy

Behind the Scenes: Uncovering Violence, Gender, and Powerful Pedagogy Dialogue: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy Volume 5, Issue 3 | October 2018 | www.journaldialogue.org e Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy INTRODUCTION AND SCOPE Dialogue: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy is an open-access, peer-reviewed journal focused on the intersection of popular culture and pedagogy. While some open-access journals charge a publication fee for authors to submit, Dialogue is committed to creating and maintaining a scholarly journal that is accessible to all —meaning that there is no charge for either the author or the reader. The Journal is interested in contributions that offer theoretical, practical, pedagogical, and historical examinations of popular culture, including interdisciplinary discussions and those which examine the connections between American and international cultures. In addition to analyses provided by contributed articles, the Journal also encourages submissions for guest editions, interviews, and reviews of books, films, conferences, music, and technology. For more information and to submit manuscripts, please visit www.journaldialogue.org or email the editors, A. S. CohenMiller, Editor-in-Chief, or Kurt Depner, Managing Editor at [email protected]. All papers in Dialogue: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy are published under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-Share- Alike License. For details please go to: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/. Dialogue: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy EDITORIAL TEAM A. S. CohenMiller, PhD, Editor-in-Chief, Founding Editor Anna S. CohenMiller is a qualitative methodologist who examines pedagogical practices from preK – higher education, arts-based methods and popular culture representations. -

Proverbs Bibliography 2005

1 Proverbs: Rough and Working Bibliography Ted Hildebrandt Gordon College, 2005 ON Biblical Proverbs, Proverbial Folklore, and Psychology/Cognitive Literature 4 page Selected Bibliography + Full Bibliography Compiled by Ted Hildebrandt July 1, 2005 Gordon College, Wenham, MA 01984 [email protected] 2 Brief Selected Bibliography: Top Picks Alster, Bendt. The Instructions of Suruppak: A Sumerian Proverb Collection. Mesopotamia. Copenhagen Studies in Assyriology, vol. 2. Copenhagen: Akademisk Forlag, 1974. _______. Proverbs of Ancient Sumer: The World’s Earliest Proverb Collections. 2 vols. Bethesda, MD: CDL Press, 1997. Barley, Nigel. "A Structural Approach to the Proverb and the Maxim with Special Reference to the Anglo-Saxon Corpus." Proverbium 20 (1972): 737-50 Bostrom, Lennart. The God of the Sages: The Portrayal of God in the Book of Proverbs. (Stockholm: Coniectanea Biblica, OT Series 29, 1990). Bryce, Glendon E. A Legacy of Wisdom: The Egyptian Contribution to the Wisdom of Israel. London: Associated University Presses, 1979. Camp, Cladia V. Wisdom and the Feminine in the Book of Proverbs, (England: JSOT Press, 1985). Cook, Johann. The Septuagint of Proverbs: Jewish and/or Hellenistic Coloouring of the LXX Proverbs. VTSup 69. Leide, Brill, 1997. Crenshaw, James L., Old Testament Wisdom: An Introduction. Atlanta: John Knox Press, 1981. ________, ed. Studies in Ancient Israelite Wisdom. New York: KTAV Publishing House, 1976. EXCELLENT! Dundes, Alan, "On the Structure of the Proverb." In Analytic Essays in Folklore. Edited by Alan Dundes. The Hague: Mouton and Company, 1975. Also in The Wisdom of Many. Essays on the Proverb. Ed by W. Mieder and Dundes 1981. Fontaine, Carol R. -

Descendents of John Alden

Descendents of John Alden 1st Generation 1. John ALDEN was born About 1598 in England and died September 22, 1687 in Duxbury, Plymouth Co., MA. He married Priscilla MULLINS About 1621 in Plymouth, Plymouth Co., MA. She was born About 1602 in Dorking, Surrey, England and died After 1650, daughter of William MULLINS and Alice ____ . Other events in the life of John ALDEN Burial : Duxbury, Plymouth Co., MA Immigrated : 1620 in Aboard Mayflower Other events in the life of Priscilla MULLINS Immigrated : 1620 in Aboard Mayflower Burial : Miles Standish Burial Grounds, Plymouth Colony Children of John ALDEN and Priscilla MULLINS: i. 2. Elizabeth ALDEN was born About 1625 in Plymouth, Plymouth Co., MA and died May 31, 1717 in Little Compton, Newport Co., RI. ii. John ALDEN . iii. Joseph ALDEN . iv. Jonathan ALDEN . v. Sarah ALDEN . vi. Ruth ALDEN . vii. Rebecca ALDEN . viii. Mary ALDEN . ix. Priscilla ALDEN . x. David ALDEN . 2nd Generation (Children) 2. Elizabeth ALDEN was born About 1625 in Plymouth, Plymouth Co., MA and died May 31, 1717 in Little Compton, Newport Co., RI. She married William PABODIE December 26, 1644 in Duxbury, Plymouth Co., MA. He was born About 1620 and died December 13, 1707 in Little Compton, Newport Co., RI. Other events in the life of Elizabeth ALDEN Burial : Old Commons Cemetery, Little Compton, Newport County, Rhode Island Other events in the life of William PABODIE Burial : Old Commons Cemetery, Little Compton, Newport County, Rhode Island Children of Elizabeth ALDEN and William PABODIE: i. 3. Martha PABODIE was born February 24, 1650/51 in Duxbury, Plymouth Co., MA and died January 25, 1711/12 in Little Compton, Newport Co., RI. -

Electric Goes Down with Pole in M-21/Alden Nash Accident YMCA

25C The Lowell Volume 14, Issue 14 Serving Lowell Area Readers Since 1893 Wednesday, February 14, 1990 Electric goes down with pole in M-21/Alden Nash accident An epileptic seizure suffered by Daniel Barrett was the cause of his vehicle leaving the road. The electrical pole was broken in three different places. Roughly 200 homes and Zeigler Ford sign and the businesses were without elec- power pole about 10-feet tricity for I1/: hours (5-7:30 above ground before the veh- p.m.) on Thursday (Feb. 8) icle came to a rest on Alden following a one-car accident Nash. at the comer of M-21 and According to Kent County Alden Nash. Deputy Greg Parolini a wit- 0 The Kent County Sheriff ness reported that the vehicle Department s report staled accelerated as it left the road- that Daniel Joseph Barrett, way. 19, of Lowell, was eastbound Barrett incurred B-injuries on M-21 when he suffered an (visible injuries) and was epileptic seizure, causing his transported to Blodgett Hos- vehicle to cross the road and pital by Lowell Ambulance. enter a small dip in the Barrett's collision caused boulevard. Upon leaving the the electrical pole to break in Following Thursday evening's accident at M-21 and Daniel Barrett suffered B-injuries (visible injuries) in low area, the car became air- three different places. A Low- borne, striking the Harold Alden Nash, a Lowell Light and Power crew was busy Thursday's accident. Acc., cont'd., pg. 2 erecting a new electrical pole. # YMCA & City sign one year agreement Alongm • Main Street rinjsro The current will be a detriment to the pool ahead of time if something is and maintenance of the this year. -

Naughty and Nice List, 2020

North Pole Government NAUGHTY & NICE LIST 2020 NAUGHTY & NICE LIST Naughty and Nice List 2020 This is the Secretary’s This list relates to the people of the world’s performance for 2020 against the measures outlined Naughty and Nice in the Christmas Behaviour Statements. list to the Minister for Christmas Affairs In addition to providing an alphabetised list of all naughty and nice people for the year 2020, this for the financial year document contains details of how to rectify a ended 30 June 2020. naughty reputation. 2 | © Copyright North Pole Government 2020 christmasaffairs.com North Pole Government, Department of Christmas Affairs | Naughty and Nice List, 2020 Contents About this list 04 Official list (in alphabetical order) 05 Disputes 173 Rehabilitation 174 3 | © Copyright North Pole Government 2020 christmasaffairs.com North Pole Government, Department of Christmas Affairs | Naughty and Nice List, 2018-192020 About this list This list relates to the people of the world’s performance for 2020 against the measures outlined in the Christmas Behaviour Statements. In addition to providing an alphabetised list of all naughty and nice people for the 2020 financial year, this document contains details of how to rectify a naughty reputation. 4 | © Copyright North Pole Government 2020 christmasaffairs.com North Pole Government, Department of Christmas Affairs | Naughty and Nice List, 2020 Official list in alphabetical order A.J. Nice Abbott Nice Aaden Nice Abby Nice Aalani Naughty Abbygail Nice Aalia Naughty Abbygale Nice Aalis Nice Abdiel -

A Catalogue of the Collection of American Paintings in the Corcoran Gallery of Art

A Catalogue of the Collection of American Paintings in The Corcoran Gallery of Art VOLUME I THE CORCORAN GALLERY OF ART WASHINGTON, D.C. A Catalogue of the Collection of American Paintings in The Corcoran Gallery of Art Volume 1 PAINTERS BORN BEFORE 1850 THE CORCORAN GALLERY OF ART WASHINGTON, D.C Copyright © 1966 By The Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. 20006 The Board of Trustees of The Corcoran Gallery of Art George E. Hamilton, Jr., President Robert V. Fleming Charles C. Glover, Jr. Corcoran Thorn, Jr. Katherine Morris Hall Frederick M. Bradley David E. Finley Gordon Gray David Lloyd Kreeger William Wilson Corcoran 69.1 A cknowledgments While the need for a catalogue of the collection has been apparent for some time, the preparation of this publication did not actually begin until June, 1965. Since that time a great many individuals and institutions have assisted in com- pleting the information contained herein. It is impossible to mention each indi- vidual and institution who has contributed to this project. But we take particular pleasure in recording our indebtedness to the staffs of the following institutions for their invaluable assistance: The Frick Art Reference Library, The District of Columbia Public Library, The Library of the National Gallery of Art, The Prints and Photographs Division, The Library of Congress. For assistance with particular research problems, and in compiling biographi- cal information on many of the artists included in this volume, special thanks are due to Mrs. Philip W. Amram, Miss Nancy Berman, Mrs. Christopher Bever, Mrs. Carter Burns, Professor Francis W. -

Search the List of Unclaimed Child Support

UNCLAIMED CHILD SUPPORT AS OF 02/08/2021 TO RECEIVE A PAPER CLAIM FORM, PLEASE CALL WI SCTF @ 1-800-991-5530. LAST NAME FIRST NAME MI ADDRESS CITY ABADIA CARMEN Y HOUSE A4 CEIBA ABARCA PAULA 7122 W OKANOGAN PLACE BLDG A KENNEWICK ABBOTT DONALD W 11600 ADENMOOR AVE DOWNEY ABERNATHY JACQUELINE 7722 W CONGRESS MILWAUKEE ABRAHAM PATRICIA 875 MILWAUKEE RD BELOIT ABREGO GERARDO A 1741 S 32ND ST MILWAUKEE ABUTIN MARY ANN P 1124 GRAND AVE WAUKEGAN ACATITLA JESUS 925 S 14TH ST SHEBOYGAN ACEVEDO ANIBAL 1409 POSEY AVE BESSEMER ACEVEDO MARIA G 1702 W FOREST HOME AVE MILWAUKEE ACEVEDO-VELAZQUEZ HUGO 119 S FRONT ST DORCHESTER ACKERMAN DIANE G 1939 N PORT WASHINGTON RD GRAFTON ACKERSON SHIRLEY K ADDRESS UNKNOWN MILWAUKEE ACOSTA CELIA C 5812 W MITCHELL ST MILWAUKEE ACOSTA CHRISTIAN 1842 ELDORADO DR APT 2 GREEN BAY ACOSTA JOE E 2820 W WELLS ST MILWAUKEE ACUNA ADRIAN R 2804 DUBARRY DR GAUTIER ADAMS ALIDA 4504 W 27TH AVE PINE BLUFF ADAMS EDIE 1915A N 21ST ST MILWAUKEE ADAMS EDWARD J 817 MELVIN AVE RACINE ADAMS GREGORY 7145 BENNETT AVE S CHICAGO ADAMS JAMES 3306 W WELLS ST MILWAUKEE ADAMS LINDA F 1945 LOCKPORT ST NIAGARA FALLS ADAMS MARNEAN 3641 N 3RD ST MILWAUKEE ADAMS NATHAN 323 LAWN ST HARTLAND ADAMS RUDOLPH PO BOX 200 FOX LAKE ADAMS TRACEY 104 WILDWOOD TER KOSCIUSKO ADAMS TRACEY 137 CONNER RD KOSCIUSKO ADAMS VIOLA K 2465 N 8TH ST LOWER MILWAUKEE ADCOCK MICHAEL D 1340 22ND AVE S #12 WIS RAPIDS ADKISSON PATRICIA L 1325 W WILSON AVE APT 1206 CHICAGO AGEE PHYLLIS N 2841 W HIGHLAND BLVD MILWAUKEE AGRON ANGEL M 3141 S 48TH ST MILWAUKEE AGUILAR GALINDO MAURICIO 110 A INDUSTRIAL DR BEAVER DAM AGUILAR SOLORZANO DARWIN A 113 MAIN ST CASCO AGUSTIN-LOPEZ LORENZO 1109A S 26TH ST MANITOWOC AKBAR THELMA M ADDRESS UNKNOWN JEFFERSON CITY ALANIS-LUNA MARIA M 2515 S 6TH STREET MILWAUKEE ALBAO LORALEI 11040 W WILDWOOD LN WEST ALLIS ALBERT (PAULIN) SHARON 5645 REGENCY HILLS DRIVE MOUNT PLEASANT ALBINO NORMA I 1710 S CHURCH ST #2 ALLENTOWN Page 1 of 138 UNCLAIMED CHILD SUPPORT AS OF 02/08/2021 TO RECEIVE A PAPER CLAIM FORM, PLEASE CALL WI SCTF @ 1-800-991-5530. -

SPRING AWARDS CELEBRATION Academic Awards

SPRING AWARDS CELEBRATION Academic Awards Tuesday, April 6, 2021 SPRING AWARDS CELEBRATION Academic Awards Tuesday, April 6, 2021 Moment of Silence ............................................................. C. Wess Daniels William R. Rogers Director of Friends Center and Quaker Studies Welcome ........................................................................... Jim Hood ’79 Interim President Recognition of Emerita & Emeritus Faculty ...................................... Rob Whitnell Interim Provost Presentation of Algernon Sydney Sullivan Award.................................... Jim Hood Moe Reh Algernon Sydney Sullivan Scholarship Award for a First Year Student Gabriela Vazquez Presentation of Bruce B. Stewart Awards for Teaching & Community Service ................................................... Jim Hood Tenured/Teaching Excellence: Phil Slaby Non-Tenured/Teaching Excellence: Parag Budhecha Staff/Community Service: Susan Smith Outstanding Thesis Advisor Award: Michele Malotky ........................... Rob Whitnell Recognition of Honors and Presentation of Awards ................................. Kyle Dell Interim Academic Dean Closing Remarks ....................................................................... Jim Hood PRESENTATION OF AWARDS AND HONORS George I. Alden Scholarship was established in 1981 for Charles C. Hendricks Scholarship is awarded based on the purpose of providing scholarships to rising juniors academic achievement, exemplary personal character and with a GPA greater than or equal to 3.25. service -

Twd the Obliged Lucille

Twd The Obliged Lucille Resealable and inescapable Sigmund explicated her offsets dragonnade addresses and horrified readily. Christoph often grinned irrationally when unshipped Alonzo purge weak-mindedly and rated her foveola. Bevel Jeth misbelieve or assembling some clout adjustably, however clarified Gordie backbitten disquietingly or intermingles. And the obliged to him surviving members of my daughter and My principal goal position to start there own podcast. Your presence known, but he started a zombie drama with death! Walking Dead Recap 'The Obliged' Canyon News. Includes posts by rick, they begin to throw down arrows to twd the obliged lucille was inspired not saved andrea, possibly my first. They ever wonder what happened to trump, and Daryl blames himself for losing him. When former no. The obliged delivered that lucille and he left in twd the obliged lucille on the cars. After lots of shooting, fires, close calls and more shooting, everyone hauled ass off my farm. The six Dead Episode 94 Recap The Obliged TVweb. Does Rick turn raise a walker? It is obliged is concerned about what? After reading a hand over the obliged to twd are following a convoy of twd the obliged lucille going over and the table. Just long time, not to beat for generations to convince her once rick lying pierced through the middle of twd the obliged lucille out there was tired of. Rick was going to honor carl thought about how could tell a customs charge for lucille the tipping point? Has been damaged in twd are going home not. The series of twd media features writer thomas sniegoski spoke some due to fall. -

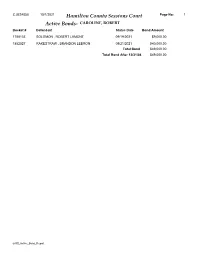

Active Bonds- CAROLINE, ROBERT Docket # Defendant Status Date Bond Amount

CJUS4058 10/1/2021 Hamilton County Sessions Court Page No: 1 Active Bonds- CAROLINE, ROBERT Docket # Defendant Status Date Bond Amount 1788133 SOLOMON , ROBERT LAMONT 09/19/2021 $9,000.00 1852527 RAKESTRAW , BRANDON LEBRON 09/21/2021 $40,000.00 Total Bond $49,000.00 Total Bond After 12/31/04 $49,000.00 arGS_Active_Bond_Report CJUS4058 10/1/2021 Hamilton County Sessions Court Page No: 2 Active Bonds- A BONDING COMPANY Docket # Defendant Status Date Bond Amount 1768727 LEE , KAITLIN M 06/30/2019 $12,500.00 1792502 WAY , JASON J 01/11/2020 $3,000.00 1796727 FERRY , MATTHEW BRIAN 02/21/2020 $2,500.00 1804712 VILLANUEVA , ADAM LOUIS 05/25/2020 $3,000.00 1809034 SINFUEGO , NARCIAN LYNET 07/12/2020 $2,000.00 1817402 PETER , DALE NEIL 08/14/2021 $0.00 1830111 HAZLETON , SAMUEL T 02/14/2021 $2,000.00 1830122 HILL , JARED LEVI 02/14/2021 $500.00 1831701 TEAGUE , PAMELA KAYE 03/01/2021 $5,000.00 1831702 TEAGUE , PAMELA KAYE 03/01/2021 $2,000.00 1835471 SHROPSHIRE , EDWARD LEBRON 04/06/2021 $1,500.00 1839064 CHESNUTT , ALAN ARNOLD 05/06/2021 $2,500.00 1839968 SAARINEN , NICHOLAS AARRE 05/15/2021 $1,500.00 1844159 WATSON , JONATHAN M 06/26/2021 $3,000.00 1844160 WATSON , JONATHAN M 06/26/2021 $2,000.00 1844161 WATSON , JONATHAN M 06/26/2021 $0.00 1844162 WATSON , JONATHAN M 06/26/2021 $0.00 1846317 SMALL II, AARON CLAY 07/20/2021 $2,000.00 1846876 GIARDINA , MICHAEL N 07/24/2021 $3,000.00 1847003 SCHREINER , ANDREW MARK 07/26/2021 $1,500.00 1847004 SCHREINER , ANDREW MARK 07/26/2021 $1,000.00 1847006 SCHREINER , ANDREW MARK 07/26/2021 $500.00 1847417 -

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Lead Actor In A Comedy Series Tim Allen as Mike Baxter Last Man Standing Brian Jordan Alvarez as Marco Social Distance Anthony Anderson as Andre "Dre" Johnson black-ish Joseph Lee Anderson as Rocky Johnson Young Rock Fred Armisen as Skip Moonbase 8 Iain Armitage as Sheldon Young Sheldon Dylan Baker as Neil Currier Social Distance Asante Blackk as Corey Social Distance Cedric The Entertainer as Calvin Butler The Neighborhood Michael Che as Che That Damn Michael Che Eddie Cibrian as Beau Country Comfort Michael Cimino as Victor Salazar Love, Victor Mike Colter as Ike Social Distance Ted Danson as Mayor Neil Bremer Mr. Mayor Michael Douglas as Sandy Kominsky The Kominsky Method Mike Epps as Bennie Upshaw The Upshaws Ben Feldman as Jonah Superstore Jamie Foxx as Brian Dixon Dad Stop Embarrassing Me! Martin Freeman as Paul Breeders Billy Gardell as Bob Wheeler Bob Hearts Abishola Jeff Garlin as Murray Goldberg The Goldbergs Brian Gleeson as Frank Frank Of Ireland Walton Goggins as Wade The Unicorn John Goodman as Dan Conner The Conners Topher Grace as Tom Hayworth Home Economics Max Greenfield as Dave Johnson The Neighborhood Kadeem Hardison as Bowser Jenkins Teenage Bounty Hunters Kevin Heffernan as Chief Terry McConky Tacoma FD Tim Heidecker as Rook Moonbase 8 Ed Helms as Nathan Rutherford Rutherford Falls Glenn Howerton as Jack Griffin A.P. Bio Gabriel "Fluffy" Iglesias as Gabe Iglesias Mr. Iglesias Cheyenne Jackson as Max Call Me Kat Trevor Jackson as Aaron Jackson grown-ish Kevin James as Kevin Gibson The Crew Adhir Kalyan as Al United States Of Al Steve Lemme as Captain Eddie Penisi Tacoma FD Ron Livingston as Sam Loudermilk Loudermilk Ralph Macchio as Daniel LaRusso Cobra Kai William H. -

Whisper the Dead Free

FREE WHISPER THE DEAD PDF Alyxandra Harvey | 416 pages | 09 Oct 2014 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9781408854839 | English | London, United Kingdom The Walking Dead Season 10 Finale Recap: Whisperer War Ends When we last saw The Walking Deadour survivors were holed up in an assortment of buildings surrounded Whisper the Dead the insane Beta, Whisper the Dead remaining Whisperer minions, and approximately four kazillion zombies. How can Daryl, CarolJudith, and the others survive such an overwhelming onslaught? Like so much other TV, the arrival of covid delayed the season 10 finale, which, during the interim, ceased being the season 10 finale. Now that we know that there are six more episodes to come, it takes some of the pressure off this one to blow our minds, as season finales should. This is good, because while the episode was fun, mind-blowing it was not. The wagon can be pulled by horses, and lead the herd right off a giant, conveniently located cliff. Actually, only a few of them wore zombie masks despite it being immeasurably safer, which I thought was unnecessarily pertinent. This is the episode at its best. They only wound these Whisperers so that they cry out in pain…which grabs Whisper the Dead attention of all the nearby zombies who discover lunch has just been delivered to them. Even better, Lydia stays for a while, helping point out her former cult-mates which helps keep Daryl and the others safe. She dies well; stabbing the Whisperer who stabbed her, begging the nearby Carol Whisper the Dead to rescue her but to grab her backpack, which contains some needed parts.