Influence of Pre-Harvest Bagging on the Incidence of Aulacaspis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cycad Aulacaspis Scale

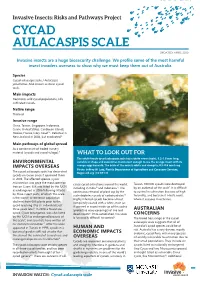

Invasive Insects: Risks and Pathways Project CYCAD AULACASPIS SCALE UPDATED: APRIL 2020 Invasive insects are a huge biosecurity challenge. We profile some of the most harmful insect invaders overseas to show why we must keep them out of Australia. Species Cycad aulacaspis scale / Aulacaspis yasumatsui. Also known as Asian cycad scale. Main impacts Decimates wild cycad populations, kills cultivated cycads. Native range Thailand. Invasive range China, Taiwan, Singapore, Indonesia, Guam, United States, Caribbean Islands, Mexico, France, Ivory Coast1,2. Detected in New Zealand in 2004, but eradicated.2 Main pathways of global spread As a contaminant of traded nursery material (cycads and cycad foliage).3 WHAT TO LOOK OUT FOR The adult female cycad aulacaspis scale has a white cover (scale), 1.2–1.6 mm long, ENVIRONMENTAL variable in shape and sometimes translucent enough to see the orange insect with its IMPACTS OVERSEAS orange eggs beneath. The scale of the male is white and elongate, 0.5–0.6 mm long. Photo: Jeffrey W. Lotz, Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, The cycad aulacaspis scale has decimated Bugwood.org | CC BY 3.0 cycads on Guam since it appeared there in 2003. The affected species, Cycas micronesica, was once the most common cause cycad extinctions around the world, Taiwan, 100,000 cycads were destroyed tree on Guam, but was listed by the IUCN 7 including in India10 and Indonesia11. The by an outbreak of the scale . It is difficult as endangered in 2006 following attacks continuous removal of plant sap by the to control in cultivation because of high by three insect pests, of which this scale scale depletes cycads of carbohydrates4,9. -

Survival of the Cycad Aulacaspis Scale in Northern Florida During Sub-Freezing Weather

furcata) (FDACS/DPI, 2002). These thrips are foliage feeders North American Plant Protection Organization’s Phytosanitary causing galling and leaf curl, which is cosmetic and has not Alert System been associated with plant decline. This feeding damage is http://www.pestalert.org only to new foliage and appears to be seasonal. This pest is be- coming established in urban areas causing concern to home- Literature Cited owners and commercial landscapers due to leaf damage. Control is difficult due to protection by leaf galls. Howev- Edwards, G. B. 2002. Pest Alert, Holopothrips sp., an Introduced Thrips Pest er, systemic insecticides are providing some control. No bio- of Trumpet Tree. March 2002. <http://doacs.state.fl.us/~pi/enpp/ ento/images/paholo-pothrips3.02.gif>. controls have been found. FDACS/DPI. 2002. TRI-OLOGY. Mar.-Apr. 2002. Fla. Dept. Agr. Cons. Serv./ Div. Plant Ind. Newsletter, vol. 41, no. 2. <http://doacs.state.fl.us/~pi/ Resources for New Insect Pest Information enpp/02-mar-apr.html>. Howard, F. W., A. Hamon, G. S. Hodges, C. M. Mannion, and J. Wofford. 2002. Lobate Lac Scale, Paratachardina lobata lobata (Chamberlin) (Hemip- The following are some web sites and list serves for addi- tera: Sternorrhyncha: Coccoidea: Kerriidae). Univ. of Fla. Cir., EENY- tional information on new insects pests in Florida. 276. <http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/IN471>. Hoy, M. A., A. Hamon, and R. Nguyen. 2003. Pink Hibiscus Mealybug, Ma- University of Florida Pest Alert conellicoccus hirsutus (Green) (Insecta: Homoptera: Pseudococcidae). http://extlab7.entnem.ufl.edu/PestAlert/ Univ. of Fla. Cir., EENY-29. <http://creatures.ifas.ufl.edu/orn/mealybug/ mealybug.htm>. -

The Scale Insect

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Bonn zoological Bulletin - früher Bonner Zoologische Beiträge. Jahr/Year: 2020 Band/Volume: 69 Autor(en)/Author(s): Caballero Alejandro, Ramos-Portilla Andrea Amalia, Rueda-Ramírez Diana, Vergara-Navarro Erika Valentina, Serna Francisco Artikel/Article: The scale insect (Hemiptera: Coccomorpha) collection of the entomological museum “Universidad Nacional Agronomía Bogotá”, and its impact on Colombian coccidology 165-183 Bonn zoological Bulletin 69 (2): 165–183 ISSN 2190–7307 2020 · Caballero A. et al. http://www.zoologicalbulletin.de https://doi.org/10.20363/BZB-2020.69.2.165 Research article urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:F30B3548-7AD0-4A8C-81EF-B6E2028FBE4F The scale insect (Hemiptera: Coccomorpha) collection of the entomological museum “Universidad Nacional Agronomía Bogotá”, and its impact on Colombian coccidology Alejandro Caballero1, *, Andrea Amalia Ramos-Portilla2, Diana Rueda-Ramírez3, Erika Valentina Vergara-Navarro4 & Francisco Serna5 1, 4, 5 Entomological Museum UNAB, Faculty of Agricultural Science, Cra 30 N° 45-03 Ed. 500, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia 2 Instituto Colombiano Agropecuario, Subgerencia de Protección Vegetal, Av. Calle 26 N° 85 B-09, Bogotá, Colombia 3 Research group “Manejo Integrado de Plagas”, Faculty of Agricultural Science, Cra 30 # 45-03 Ed. 500, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia 4 Corporación Colombiana de Investigación Agropecuaria AGROSAVIA, Research Center Tibaitata, Km 14, via Mosquera-Bogotá, Cundinamarca, Colombia * Corresponding author: Email: [email protected]; [email protected] 1 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:A4AB613B-930D-4823-B5A6-45E846FDB89B 2 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:B7F6B826-2C68-4169-B965-1EB57AF0552B 3 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:ECFA677D-3770-4314-A73B-BF735123996E 4 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:AA36E009-D7CE-44B6-8480-AFF74753B33B 5 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:E05AE2CA-8C85-4069-A556-7BDB45978496 Abstract. -

Report and Recommendations on Cycad Aulacaspis Scale, Aulacaspis Yasumatsui Takagi (Hemiptera: Diaspididae)

IUCN/SSC Cycad Specialist Group – Subgroup on Invasive Pests Report and Recommendations on Cycad Aulacaspis Scale, Aulacaspis yasumatsui Takagi (Hemiptera: Diaspididae) 18 September 2005 Subgroup Members (Affiliated Institution & Location) • William Tang, Subgroup Leader (USDA-APHIS-PPQ, Miami, FL, USA) • Dr. John Donaldson, CSG Chair (South African National Biodiversity Institute & Kirstenbosch National Botanical Garden, Cape Town, South Africa) • Jody Haynes (Montgomery Botanical Center, Miami, FL, USA)1 • Dr. Irene Terry (Department of Biology, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, USA) Consultants • Dr. Anne Brooke (Guam National Wildlife Refuge, Dededo, Guam) • Michael Davenport (Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden, Miami, FL, USA) • Dr. Thomas Marler (College of Natural & Applied Sciences - AES, University of Guam, Mangilao, Guam) • Christine Wiese (Montgomery Botanical Center, Miami, FL, USA) Introduction The IUCN/SSC Cycad Specialist Group – Subgroup on Invasive Pests was formed in June 2005 to address the emerging threat to wild cycad populations from the artificial spread of insect pests and pathogens of cycads. Recently, an aggressive pest on cycads, the cycad aulacaspis scale (CAS)— Aulacaspis yasumatsui Takagi (Hemiptera: Diaspididae)—has spread through human activity and commerce to the point where two species of cycads face imminent extinction in the wild. Given its mission of cycad conservation, we believe the CSG should clearly focus its attention on mitigating the impact of CAS on wild cycad populations and cultivated cycad collections of conservation importance (e.g., Montgomery Botanical Center). The control of CAS in home gardens, commercial nurseries, and city landscapes is outside the scope of this report and is a topic covered in various online resources (see www.montgomerybotanical.org/Pages/CASlinks.htm). -

Road Map for Developing & Strengthening The

KENYA ROAD MAP FOR DEVELOPING & STRENGTHENING THE PROCESSED MANGO SECTOR DECEMBER 2014 TRADE IMPACT FOR GOOD The designations employed and the presentation of material in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the International Trade Centre concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. This document has not formally been edited by the International Trade Centre. ROAD MAP FOR DEVELOPING & STRENGTHENING THE KENYAN PROCESSED MANGO SECTOR Prepared for International Trade Centre Geneva, december 2014 ii This value chain roadmap was developed on the basis of technical assistance of the International Trade Centre ( ITC ). Views expressed herein are those of consultants and do not necessarily coincide with those of ITC, UN or WTO. Mention of firms, products and product brands does not imply the endorsement of ITC. This document has not been formally edited my ITC. The International Trade Centre ( ITC ) is the joint agency of the World Trade Organisation and the United Nations. Digital images on cover : © shutterstock Street address : ITC, 54-56, rue de Montbrillant, 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Postal address : ITC Palais des Nations 1211 Geneva, Switzerland Telephone : + 41- 22 730 0111 Postal address : ITC, Palais des Nations, 1211 Geneva, Switzerland Email : [email protected] Internet : http :// www.intracen.org iii ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS Unless otherwise specified, all references to dollars ( $ ) are to United States dollars, and all references to tons are to metric tons. The following abbreviations are used : AIJN European Fruit Juice Association BRC British Retail Consortium CPB Community Business Plan DC Developing countries EFTA European Free Trade Association EPC Export Promotion Council EU European Union FPEAK Fresh Produce Exporters Association of Kenya FT Fairtrade G.A.P. -

Survey of the Scale Insects and Mealybugs Species and Its Associated Natural Enemies on Mango Trees in Different Governorates In

Benha Journal of Applied Sciences (BJAS) print : ISSN 2356–9751 Vol.(2) Issue(2) Nov.(2017), 75-82 online : ISSN 2356–976x http:// bjas.bu.edu.eg Survey of the Scale Insects and Mealybugs Species and its Associated Natural Enemies on Mango Trees in Different Governorates in Egypt E.S.M.Amer1, M.ASalem2, M.E.H.Hanafy2 and N.Ahmed1 1Plant Protection Research Institute, A.R.C, Dokii, Giza, Egypt 2Plant Protection Dept., Faculty of Agriculture, Ain shams Univ., Egypt E-Mail: [email protected] Abstract Studies on survey of scale insects and mealybugs infested mango trees and its associated parasitoids and predators were carried out at five governorates in Egypt during two successive years (2013- 2014 and 2014- 2015). The obtained results provided the occurrence of ten scale insects and mealybugs species found on mango trees. These species were Kilifia acuminata (Signoret), Ceroplastes floridensis Comstock, Aulacaspis tubercularis Newstead, Pulvinaria psidii (Maskell), Aonidiella aurantii (Maskell), Lepidosaphes pallidula (Maskell), Planococcus citri Risso, Icerya seychellarum (Westwood), Maconellicoccus hirsutus (Green) and Hemiberlesia lataniae (Signoret). Also, We recorded many species of parasitoids were associated with scale insects and mealybugs during two years of study. The parasitoids species were Metaphycus flavus (Haward), Habrolepis aspidioti( Compere & Annecke), Encarsia citrine Craw, Aphytis chrysomphali Mercet and Aphytis lepidosaphes Compere and we recorded several of predators were associated with scale insects and mealybugs, Rodalia cardinalis (Mulsant), Scymnus syriacus (Marseul), Exochomus flavipes (Thunberg) and Hemisarcoptes coccophagus (Meyer). Key words: Survey, Scale insects and mealybugs, Parasitoids and predators, Mango trees, Egypt. 1. Introduction for survey study during the period from January Mango Mangifera indica L. -

Mango Fruit Quality Improvements in Response to Water Stress: Implications for Adaptation Under Environmental Constraints

Horticultural Science (Prague), 48, 2021 (1): 1–11 Original Paper https://doi.org/10.17221/45/2020-HORTSCI Mango fruit quality improvements in response to water stress: implications for adaptation under environmental constraints Víctor Hugo Durán Zuazo1*, Dionisio Franco Tarifa2, Belén Cárceles Rodríguez1, Baltasar Gálvez Ruiz1, Pedro Cermeño Sacristán3, Simón Cuadros Tavira4, Iván Francisco García-Tejero3 1IFAPA Centro “Camino de Purchil”, Granada, Spain 2Auntamiento de Almuñécar, Almuñécar, Spain 3IFAPA Centro “Las Torres”, Sevilla, Spain 4Departemento de Ingeniería Forestal, Universidad de Córdoba, Córdoba, Spain *Corresponding author: [email protected] Citation: Durán Zuazo V.H., Franco T.D., Cárceles R.B., Gálvez R.B., Cermeño S.P., Cuadros T.S., García T.I.F. (2021): Mango fruit quality improvements in response to water stress: implications for adaptation under environmental con- straints. Hort. Sci. (Prague), 48: 1–11. Abstract: Mediterranean farming is facing increasing periods of water shortage and, in the coming decades, the water reduction is expected to exert the most adverse impact upon growth and productivity. This study was performed to assess the response of the physico-biochemical quality parameters of mango fruits to different doses of irrigation in a Mediterranean subtropical area in Spain. During two-monitoring seasons, trees were subjected to deficit-irrigation strategies receiving 33, 50, and 75% of a crop evapotranspiration (ETC), and a control at 100% ETC. According to the findings and respect to control, the yield was reduced in 8, 11, and 20% for the water-stressed trees at 75, 50, and 33% ETC, respectively, producing smaller fruits in line with the amount of applied irrigation. -

Ants: Major Functional Elements in Fruit Agro-Ecosystems and Biological Control Agents

sustainability Review Ants: Major Functional Elements in Fruit Agro-Ecosystems and Biological Control Agents Lamine Diamé 1,2,*, Jean-Yves Rey 1,3,6, Jean-François Vayssières 3,6, Isabelle Grechi 4,6, Anaïs Chailleux 3,5,6 ID and Karamoko Diarra 2 1 Institut Sénégalais de Recherches Agricoles, Centre pour le Développement de l’Horticulture, BP 3120 Dakar, Senegal; [email protected] 2 Université Cheikh Anta Diop de Dakar, BP 7925 Dakar, Senegal; [email protected] 3 Centre de Coopération Internationale de Recherche Agronomique pour le Développement, UPR HortSys, F-34398 Montpellier, France; jean-franç[email protected] (J.F.V.); [email protected] (A.C.) 4 Centre de Coopération Internationale de Recherche Agronomique pour le Développement, UPR HortSys, F-97455 Saint-Pierre, La Réunion, France; [email protected] 5 Biopass, Institut Sénégalais de Recherches Agricoles—University Cheikh Anta Diop de Dakar—Institut de Recherche pour le Développement, BP 2274 Dakar, Senegal 6 University de Montpellier, Centre de Coopération Internationale de Recherche Agronomique pour le Développement, HortSys, F-34398 Montpellier, France * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 15 October 2017; Accepted: 12 December 2017; Published: 22 December 2017 Abstract: Ants are a very diverse taxonomic group. They display remarkable social organization that has enabled them to be ubiquitous throughout the world. They make up approximately 10% of the world’s animal biomass. Ants provide ecosystem services in agrosystems by playing a major role in plant pollination, soil bioturbation, bioindication, and the regulation of crop-damaging insects. Over recent decades, there have been numerous studies in ant ecology and the focus on tree cropping systems has given added importance to ant ecology knowledge. -

Evaluation of Certain Mineral Salts and Microelements Against Mango Powdery Mildew Under Egyptian Conditions

Journal of Phytopathology and Pest Management 3(3): 35-42, 2016 pISSN:2356-8577 eISSN: 2356-6507 Journal homepage: http://ppmj.net/ Evaluation of certain mineral salts and microelements against mango powdery mildew under Egyptian conditions Fatma A. Mostafa*, S. A. El Sharkawy Plant Pathology Research Institute, Agricultural Research Center, Giza, Egypt. Abstract During the two successive seasons 2014 and 2015, three mineral salts used as commercial fertilizers (Potassium di -hydrogen orthophosphate, Potassium bicarbonate (85%), Calcium nitrate (17.1%)) and four microelements (Magnesium sulfate, Iron cheated (Fe-EDTA 6%), Zinc cheated (Zn-EDTA 12%), Manganese cheated (Mn-EDTA 12%)) were evaluated against powdery mildew of mango caused by Oidium mangiferea. Data obtained showed that all materials reduced significantly the disease severity percentage of mango powdery mildew disease comparing the control. Compared fungicides; Topsin M 70 (Thiophanate methyl) and Topas 10% (Penconazole) showed the most superior effect against the disease followed by potassium di-hydrogen orthophosphate. Tested microelements were arranged as zinc, iron and manganese, respectively due to their efficiency. Calcium nitrate and magnesium sulfate revealed the less effect. Evaluated microelements showed the higher efficacy than mineral fertilizers during the two experimental seasons except potassium monophosphate. While, two compared fungicides were the most efficiency to control the disease, tested materials reduced significantly the disease severity of mango powdery mildew disease and showed ability to reduce the number of required applications with conventional fungicides. Key words: Mango, powdery mildew, mineral salts, microelements, thiophonate methyl, penconazole. Copyright © 2016 ∗ Corresponding author: Fatma A. Mostafa, E-mail: [email protected] 35 Mostafa Fatma & El Sharkawy, 2016 Introduction addition, plant diseases play a limiting role in agricultural production. -

Tree-Ripe Mango Fruit: Physicochemical Characterization, Antioxidant Properties and Sensory Profile of Six Mediterranean-Grown Cultivars

agronomy Article Tree-Ripe Mango Fruit: Physicochemical Characterization, Antioxidant Properties and Sensory Profile of Six Mediterranean-Grown Cultivars Vittorio Farina 1 , Carla Gentile 2 , Giuseppe Sortino 1,* , Giuseppe Gianguzzi 1 , Eristanna Palazzolo 1 and Agata Mazzaglia 3 1 Department of Agricultural, Food and Forest Sciences (SAAF), Università degli Studi di Palermo, edificio 4, 90128 Palermo, Italy; [email protected] (V.F.); [email protected] (G.G.); [email protected] (E.P.) 2 Department of Biological, Chemical and Pharmaceutical Sciences and Technologies (STEBICEF), University of Palermo, Viale delle Scienze, 90128 Palermo, Italy; [email protected] 3 Department of Agricultural, Food and Environmental, Università degli Studi di Catania, via S. Sofia, 98-95123 Catania, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-091123861234 Received: 31 May 2020; Accepted: 18 June 2020; Published: 19 June 2020 Abstract: Some of the key components that contribute to the acceptance of high-quality fresh mangoes by consumers are its flavour, odour, texture and chemical constituents that depend mainly on level of maturity. In the European market, the demand for tree-ripened fruit has increased in recent decades. Nevertheless, the qualitative response and the marketable characteristics of tree-ripened mango fruit grown in the Mediterranean area are not yet studied. Tree-ripened fruits of cv Keitt, Glenn, Osteen, Maya, Kensington Pride and Tommy Atkins were submitted to analytical (fruit weight, transversal diameter, longitudinal diameter, flesh firmness, total soluble solid content, titratable acidity, seed weight, peel weight, percentage of flesh and fibre, ash content, fat content, carbohydrate content, riboflavin, niacin, thiamin, K, Na, Ca, Mg, Fe, Cu, Mn and Zn contents, ascorbic acid and vitamin A) and sensory evaluations. -

Scale Insects (Hemiptera: Coccomorpha) in the Entomological Collection of the Zoology Research Group, University of Silesia in Katowice (DZUS), Poland

Bonn zoological Bulletin 70 (2): 281–315 ISSN 2190–7307 2021 · Bugaj-Nawrocka A. et al. http://www.zoologicalbulletin.de https://doi.org/10.20363/BZB-2021.70.2.281 Research article urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:DAB40723-C66E-4826-A8F7-A678AFABA1BC Scale insects (Hemiptera: Coccomorpha) in the entomological collection of the Zoology Research Group, University of Silesia in Katowice (DZUS), Poland Agnieszka Bugaj-Nawrocka1, *, Łukasz Junkiert2, Małgorzata Kalandyk-Kołodziejczyk3 & Karina Wieczorek4 1, 2, 3, 4 Faculty of Natural Sciences, Institute of Biology, Biotechnology and Environmental Protection, University of Silesia in Katowice, Bankowa 9, PL-40-007 Katowice, Poland * Corresponding author: Email: [email protected] 1 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:B5A9DF15-3677-4F5C-AD0A-46B25CA350F6 2 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:AF78807C-2115-4A33-AD65-9190DA612FB9 3 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:600C5C5B-38C0-4F26-99C4-40A4DC8BB016 4 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:95A5CB92-EB7B-4132-A04E-6163503ED8C2 Abstract. Information about the scientific collections is made available more and more often. The digitisation of such resources allows us to verify their value and share these records with other scientists – and they are usually rich in taxa and unique in the world. Moreover, such information significantly enriches local and global knowledge about biodiversi- ty. The digitisation of the resources of the Zoology Research Group, University of Silesia in Katowice (Poland) allowed presenting a substantial collection of scale insects (Hemiptera: Coccomorpha). The collection counts 9369 slide-mounted specimens, about 200 alcohol-preserved samples, close to 2500 dry specimens stored in glass vials and 1319 amber inclu- sions representing 343 taxa (289 identified to species level), 158 genera and 36 families (29 extant and seven extinct). -

Invasive Alien Species in Protected Areas

INVASIVE ALIEN SPECIES AND PROTECTED AREAS A SCOPING REPORT Produced for the World Bank as a contribution to the Global Invasive Species Programme (GISP) March 2007 PART I SCOPING THE SCALE AND NATURE OF INVASIVE ALIEN SPECIES THREATS TO PROTECTED AREAS, IMPEDIMENTS TO IAS MANAGEMENT AND MEANS TO ADDRESS THOSE IMPEDIMENTS. Produced by Maj De Poorter (Invasive Species Specialist Group of the Species Survival Commission of IUCN - The World Conservation Union) with additional material by Syama Pagad (Invasive Species Specialist Group of the Species Survival Commission of IUCN - The World Conservation Union) and Mohammed Irfan Ullah (Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment, Bangalore, India, [email protected]) Disclaimer: the designation of geographical entities in this report does not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN, ISSG, GISP (or its Partners) or the World Bank, concerning the legal status of any country, territory or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delineation of its frontiers or boundaries. 1 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS...........................................................................................4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...........................................................................................6 GLOSSARY ..................................................................................................................9 1 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................12 1.1 Invasive alien