Retracing the Penutian Expansion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring/Summer 2018

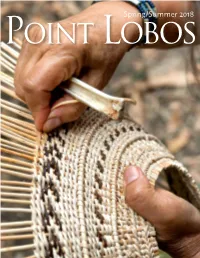

Spring/Summer 2018 Point Lobos Board of Directors Sue Addleman | Docent Administrator Kit Armstrong | President Chris Balog Jacolyn Harmer Ben Heinrich | Vice President Karen Hewitt Loren Hughes Diana Nichols Julie Oswald Ken Ruggerio Jim Rurka Joe Vargo | Secretary John Thibeau | Treasurer Cynthia Vernon California State Parks Liaison Sean James | [email protected] A team of State Parks staff, Point Lobos Docents and community volunteers take a much-needed break after Executive Director restoring coastal bluff habitat along the South Shore. Anna Patterson | [email protected] Development Coordinator President’s message 3 Tracy Gillette Ricci | [email protected] Kit Armstrong Docent Coordinator and School Group Coordinator In their footsteps 4 Melissa Gobell | [email protected] Linda Yamane Finance Specialist Shell of ages 7 Karen Cowdrey | [email protected] Rae Schwaderer ‘iim ‘aa ‘ishxenta, makk rukk 9 Point Lobos Magazine Editor Reg Henry | [email protected] Louis Trevino Native plants and their uses 13 Front Cover Chuck Bancroft Linda Yamane weaves a twined work basket of local native plant materials. This bottomless basket sits on the rim of a From the editor 15 shallow stone mortar, most often attached to the rim with tar. Reg Henry Photo: Neil Bennet. Notes from the docent log 16 Photo Spread, pages 10-11 Compiled by Ruthann Donahue Illustration of Rumsen life by Linda Yamane. Acknowledgements 18 Memorials, tributes and grants Crossword 20 Ann Pendleton Our mission is to protect and nurture Point Lobos State Natural Reserve, to educate and inspire visitors to preserve its unique natural and cultural resources, and to strengthen the network of Carmel Area State Parks. -

The Wintu and Their Neighbors: a Very Small World-System

THE WINTU AND THEIR NEIGHBORS: A VERY SMALL WORLD-SYSTEM Christopher Chase-Dunn Department of Sociology Johns Hopkins University Baltimore, ND 21218 ABSTRACT The world-systems perspective analyzes the modern international system. This approach can be applied to long range social evolution by studying smaller regional intersocietal systems such as the late pre-contact Wintu and their neighbors. Three questions: 1. What was the nature of integration among wintu groups and between them and neighboring groups? 2. What are the spatial characteristics of this network regarding fall off of the impact of events? 3. Was there regional soc~ally structured inequality in this system? Archaeological data may allow estimation of extent and rate of Wintu expansion, obsidian trade patterns, settlement sizes, and other features of this little world-system. INTRODUCTION This paper describes a theoretical approach for the comparative study of world-systems and a preliminary consideration of a small regional intersocietal system composed of the Wintu people and their neighbors in Northern California. I am currently engaged in the study of two "cases" of relatively small intersocietal networks -- the Wintu-centered system and late prehistoric Hawaii (Chase-Dunn 1991). This paper describes my preliminary hypotheses and examines possibilities for using archaeological, ethnographic, and documentary evidence for answering questions raised by the world-systems perspective. The world-systems perspective is a theoretical approach which has been developed to analyze the dynamics of the Europe centered, and now-global, political economy composed of national societies (cf. Wallerstein 1974, 1979; Chase-Dunn 1989; and a very readable introduction in Shannon 1989). One important structure in this modern world-system is the core/periphery hierarchy -- a stratified system of relations among dominant "advanced" core states and dependent and "underdeveloped" peripheral areas. -

California Indian Food and Culture PHOEBE A

California Indian Food and Culture PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY Written and Designed by Nicole Mullen Contributors: Ira Jacknis, Barbara Takiguchi, and Liberty Winn. Sources Consulted The former exhibition: Food in California Indian Culture at the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology. Ortiz, Beverly, as told by Julia Parker. It Will Live Forever. Heyday Books, Berkeley, CA 1991. Jacknis, Ira. Food in California Indian Culture. Hearst Museum Publications, Berkeley, CA, 2004. Copyright © 2003. Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology and the Regents of the University of California, Berkeley. All Rights Reserved. PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY Table of Contents 1. Glossary 2. Topics of Discussion for Lessons 3. Map of California Cultural Areas 4. General Overview of California Indians 5. Plants and Plant Processing 6. Animals and Hunting 7. Food from the Sea and Fishing 8. Insects 9. Beverages 10. Salt 11. Drying Foods 12. Earth Ovens 13. Serving Utensils 14. Food Storage 15. Feasts 16. Children 17. California Indian Myths 18. Review Questions and Activities PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY Glossary basin an open, shallow, usually round container used for holding liquids carbohydrate Carbohydrates are found in foods like pasta, cereals, breads, rice and potatoes, and serve as a major energy source in the diet. Central Valley The Central Valley lies between the Coast Mountain Ranges and the Sierra Nevada Mountain Ranges. It has two major river systems, the Sacramento and the San Joaquin. Much of it is flat, and looks like a broad, open plain. It forms the largest and most important farming area in California and produces a great variety of crops. -

The Carmel Pine Cone

VolumeThe 105 No. 42 Carmelwww.carmelpinecone.com Pine ConeOctober 18-24, 2019 T RUS T ED BY LOCALS AND LOVED BY VISI T ORS SINCE 1 9 1 5 Deal pending for Esselen tribe to buy ranch Cal Am takeover By CHRIS COUNTS But the takeover is not a done deal yet, despite local media reports to the contrary, Peter Colby of the Western study to be IF ALL goes according to plan, it won’t be a Silicon Rivers Conservancy told The Pine Cone this week. His Valley executive or a land conservation group that soon group is brokering the deal between the current owner of takes ownership of a remote 1,200-acre ranch in Big Sur the ranch, the Adler family of Sweden, and the Esselen released Nov. 6 but a Native American tribe with deep local roots. Tribe of Monterey County. “A contract for the sale is in place, By KELLY NIX but a number of steps need to be com- pleted first before the land is trans- THE LONG-AWAITED findings of a study to deter- ferred,” Colby said. mine the feasibility of taking over California American While Colby didn’t say how much Water’s local system and turning it into a government-run the land is selling for, it was listed operation will be released Nov. 6, the Monterey Peninsula at $8 million when The Pine Cone Water Management District announced this week. reported about it in 2017. But ear- The analysis was launched after voters in November lier this month, the California Nat- 2018 OK’d a ballot measure calling for the water district ural Resources Agency announced to use eminent domain, if necessary, to acquire Cal Am’s that something called “the Esselen Monterey Peninsula water system if the move was found Tribal Lands Conservation Project” to be cost effective. -

White Salmon Planning Commission Meeting AGENDA February 24, 2021

White Salmon Planning Commission Meeting AGENDA February 24, 2021 – 5:30 PM Via Zoom Teleconference Meeting ID: 840 1289 8223 Passcode: 623377 Call in Numbers: 669-900-6833 929-205-6099 301-715-8592 346-248-7799 253-215-8782 312-626-6799 We ask that the audience call in instead of videoing in or turn off your camera, so video does not show during the meeting to prevent disruption. Thank you. Call to Order/Roll Call Public Comment – Draft Elements 1. Public comment will not be taken during the teleconference. Public comment submitted by email to Jan Brending at [email protected] by 5:00 p.m. on Wednesday, February 24, 2021 will be read during the planning commission meeting and forwarded to all planning commissioners. Please include in the subject line "Public Comment - February 24, 2021 - Planning Commission Meeting." Please indicate whether you live in or outside of the city limits of White Salmon. Discussion Items 2. Presentation and Discussion of Draft Elements a. History and Historic Places b. Transportation c. Public Facilities and Services d. Capital Improvement Program 3. Comprehensive Plan Update Workshop a. Environmental Quality and Critical Areas Element b. Economics Element c. Parks and Recreation Element d. HIstory and Historic Places Element (if time allows) Adjournment 1 File Attachments for Item: 2. Presentation and Discussion of Draft Elements a. HIstory and HIstoric Places b. Transportation c. Public Facilities and Services d. Capital Improvement Program 2 II. HISTORY AND HISTORIC PLACES Background Context and History Environmental context The City of White Salmon lies in a transition zone between the maritime climate west of the Cascade Mountain Range and the dry continental climate of the inter-mountain region to the east. -

Some Morphological Parallels Between Hokan Languages1

Mikhail Zhivlov Russian State University for the Humanities; School for Advanced Studies in the Humanities, RANEPA (Moscow); [email protected] Some morphological parallels between Hokan languages1 In this paper I present a detailed analysis of a number of morphological comparisons be- tween the branches of the hypothetical Hokan family. The following areas are considered: 1) subject person/number markers on verbs, as well as possessor person/number markers on nouns, 2) so-called ‘lexical prefixes’ denoting instrument and manner of action on verbs, 3) plural infixes, used with both nouns and verbs, and 4) verbal directional suffixes ‘hither’ and ‘thither’. It is shown that the respective morphological parallels can be better accounted for as resulting from genetic inheritance rather than from areal diffusion. Keywords: Hokan languages, Amerindian languages, historical morphology, genetic vs. areal relationship 0. The Hokan hypothesis, relating several small language families and isolates of California, was initially proposed by Dixon and Kroeber (1913) more than a hundred years ago. There is still no consensus regarding the validity of Hokan: some scholars accept the hypothesis (Kaufman 1989, 2015; Gursky 1995), while others view it with great skepticism (Campbell 1997: 290–296, Marlett 2007; cf. a more positive assessment in Golla 2011: 82–84, as well as a neutral overview in Jany 2016). My own position is that the genetic relationship between most languages usually subsumed under Hokan is highly likely, and that the existence of the Ho- kan family can be taken as a working hypothesis, subject to further proof or refutation. The goal of the present paper is to draw attention to several morphological parallels be- tween Hokan languages. -

Hood River – White Salmon Interstate Bridge Replacement Project SDEIS

(OR SHPO Case No. 19-0587; WA DAHP Project Tracking Code: 2019-05-03456) Draft Historic Resources Technical Report October 1, 2020 Prepared for: Prepared by: In coordination with: 111 SW Columbia 851 SW Sixth Avenue Suite 1500 Suite 1600 Portland, Oregon 97201 Portland, Oregon 97204 This page intentionally left blank. TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................. 1 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 1 2. Project Alternatives ....................................................................................................................... 3 2.1. No Action Alternative .......................................................................................................... 7 2.2. Preferred Alternative EC-2 ................................................................................................... 8 2.3. Alternative EC-1 ................................................................................................................ 14 2.4. Alternative EC-3 ................................................................................................................ 19 2.5. Construction of the Build Alternatives ............................................................................... 23 3. Methodology .............................................................................................................................. -

THE VOWEL SYSTEMS of CALIFORNIA HOKAN1 Jeff Good University of California, Berkeley

THE VOWEL SYSTEMS OF CALIFORNIA HOKAN1 Jeff Good University of California, Berkeley Unlike the consonants, the vowels of Hokan are remarkably conservative. —Haas (1963:44) The evidence as I view it points to a 3-vowel proto-system consisting of the apex vowels *i, *a, *u. —Silver (1976:197) I am not willing, however, to concede that this suggests [Proto-Hokan] had just three vowels. The issue is open, though, and I could change my mind. —Kaufman (1988:105) 1. INTRODUCTION. The central question that this paper attempts to address is the motivation for the statements given above. Specifically, assuming there was a Proto-Hokan, what evidence is there for the shape of its vowel system? With the exception of Kaufman’s somewhat equivocal statement above, the general (but basically unsupported) verdict has been that Proto-Hokan had three vowels, *i, *a, and *u. This conclusion dates back to at least Sapir (1917, 1920, 1925) who implies a three-vowel system in his reconstructions of Proto-Hokan forms. However, as far as I am aware, no one has carefully articulated why they think the Proto-Hokan system should have been of one form instead of another (though Kaufman (1988) does discuss some of his reasons).2 Furthermore, while reconstructions of Proto-Hokan forms exist, it has not yet been possible to provide a detailed analysis of the sound changes required to relate reconstructed forms to attested forms. As a result, even though the reconstructions themselves are valuable, they cannot serve as a strong argument for the particular proto vowel system they implicitly or explicitly assume. -

Linguistic Evidence for a Prehistoric Polynesia—Southern California Contact Event

Linguistic Evidence for a Prehistoric Polynesia—Southern California Contact Event KATHRYN A. KLAR University of California, Berkeley TERRY L. JONES California Polytechnic State University Abstract. We describe linguistic evidence for at least one episode of pre- historic contact between Polynesia and Native California, proposing that a borrowed Proto—Central Eastern Polynesian lexical compound was realized as Chumashan tomol ‘plank canoe’ and its dialect variants. Similarly, we suggest that the Gabrielino borrowed two Polynesian forms to designate the ‘sewn- plank canoe’ and ‘boat’ (in general, though probably specifically a dugout). Where the Chumashan form speaks to the material from which plank canoes were made, the Gabrielino forms specifically referred to the techniques (adzing, piercing, sewing). We do not suggest that there is any genetic relationship between Polynesian languages and Chumashan or Gabrielino, only that the linguistic data strongly suggest at least one prehistoric contact event. Introduction. Arguments for prehistoric contact between Polynesia and what is now southern California have been in print since the late nineteenth century when Lang (1877) suggested that the shell fishhooks used by Native Hawaiians and the Chumash of Southern California were so stylistically similar that they had to reflect a shared cultural origin. Later California anthropologists in- cluding the archaeologist Ronald Olson (1930) and the distinguished Alfred Kroeber (1939) suggested that the sewn-plank canoes used by the Chumash and the Gabrielino off the southern California coast were so sophisticated and uni- que for Native America that they likely reflected influence from Polynesia, where plank sewing was common and widespread. However, they adduced no linguistic evidence in support of this hypothesis. -

1. Introduction

1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Ethnographic setting The Chimariko language was spoken in the nineteenth century in a few small villages in Trinity County, in north-western California. The villages were located along a twenty-mile stretch of the Trinity River and parts of the New River and South Fork River. In 1849, the Chimariko numbered around two hundred and fifty people. They were nearly extinct in 1906, except for a ‘toothless old woman and a crazy old man’, as well as ‘a few mixed bloods’ (Kroeber 1925:109). The ‘toothless old woman’ Kroeber refers to was most likely Polly Dyer and the ‘crazy old man’ Dr. Tom, also identified by Dixon (1910:295) as a ‘half-crazy old man’. The last speaker probably died in the 1940s. First contact with European explorers occurred early in the nineteenth century, in the 1820s or 1830s, when fur trappers came to the region. However, the tribe was left largely unaffected by this encounter (Dixon 1910:297). During the Gold Rush in the 1850s the Chimariko territory was overrun by gold seekers. Continuous gold mining activities in the region threatened the salmon supply, the main food source of the tribe, and led to a bitter conflict in the 1860s (Silver 1978a:205). The fights between European miners and the tribe resulted in the near annihilation of the Chimariko in the 1860s. The few survivors took refuge with the neighboring Shasta on the upper Salmon River or in Scott Valley or with the Hupa to the northwest (Dixon 1910:297). Once the gold was gone and the miners left the region, the survivors returned to their homes after years in exile (Silver 1978a:205). -

The Geography and Dialects of the Miwok Indians

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PUBLICATIONS IN AMERICAN ARCHAEOLOGY AND ETHNOLOGY VOL. 6 NO. 2 THE GEOGRAPHY AND DIALECTS OF THE MIWOK INDIANS. BY S. A. BARRETT. CONTENTS. PAGE Introduction.--...--.................-----------------------------------333 Territorial Boundaries ------------------.....--------------------------------344 Dialects ...................................... ..-352 Dialectic Relations ..........-..................................356 Lexical ...6.................. 356 Phonetic ...........3.....5....8......................... 358 Alphabet ...................................--.------------------------------------------------------359 Vocabularies ........3......6....................2..................... 362 Footnotes to Vocabularies .3.6...........................8..................... 368 INTRODUCTION. Of the many linguistic families in California most are con- fined to single areas, but the large Moquelumnan or Miwok family is one of the few exceptions, in that the people speaking its various dialects occupy three distinct areas. These three areas, while actually quite near together, are at considerable distances from one another as compared with the areas occupied by any of the other linguistic families that are separated. The northern of the three Miwok areas, which may for con- venience be called the Northern Coast or Lake area, is situated in the southern extremity of Lake county and just touches, at its northern boundary, the southernmost end of Clear lake. This 334 University of California Publications in Am. Arch. -

Soc 1-1 10.1 Socioeconomics Resource Study (Soc 1)

PacifiCorp/Cowlitz PUD Lewis River Hydroelectric Projects FERC Project Nos. 935, 2071, 2111, 2213 TABLE OF CONTENTS 10.0 SOCIOECONOMICS.................................................................................... SOC 1-1 10.1 SOCIOECONOMICS RESOURCE STUDY (SOC 1).......................... SOC 1-1 10.1.1 Study Objectives......................................................................... SOC 1-1 10.1.2 Study Area .................................................................................. SOC 1-2 10.1.3 Methods ...................................................................................... SOC 1-5 10.1.4 Key Questions............................................................................. SOC 1-7 10.1.5 Results......................................................................................... SOC 1-8 10.1.6 Discussion................................................................................. SOC 1-49 10.1.7 Schedule.................................................................................... SOC 1-51 10.1.8 References................................................................................. SOC 1-52 10.1.9 Comments and Responses on Draft Report .............................. SOC 1-57 SOC 1 Appendix 1 Text of RCW 54.28.050 SOC 1 Appendix 2 Descriptive Text of Money Generation Model LIST OF TABLES Table 10.1-1. Local sources of socioeconomic information...................................SOC 1-5 Table 10.1-2. 1990 population distribution by age in the secondary study area. ................................................................................................SOC