Hood River – White Salmon Interstate Bridge Replacement Project SDEIS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interstate Bridge Replacement Program December 2019 Progress Report

Interstate Bridge Replacement Program December 2019 Progress Report December 2019 Progress Report i This page intentionally left blank. ii Interstate Bridge Replacement Program December 2, 2019 (Electronic Transmittal Only) The Honorable Governor Inslee The Honorable Kate Brown WA Senate Transportation Committee Oregon Transportation Commission WA House Transportation Committee OR Joint Committee on Transportation Dear Governors, Transportation Commission, and Transportation Committees: On behalf of the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) and the Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT), we are pleased to submit the Interstate Bridge Replacement Program status report, as directed by Washington’s 2019-21 transportation budget ESHB 1160, section 306 (24)(e)(iii). The intent of this report is to share activities that have lead up to the beginning of the biennium, accomplishments of the program since funding was made available, and future steps to be completed by the program as it moves forward with the clear support of both states. With the appropriation of $35 million in ESHB 1160 to open a project office and restart work to replace the Interstate Bridge, Governor Inslee and the Washington State Legislature acknowledged the need to renew efforts for replacement of this aging infrastructure. Governor Kate Brown and the Oregon Transportation Commission (OTC) directed ODOT to coordinate with WSDOT on the establishment of a project office. The OTC also allocated $9 million as the state’s initial contribution, and Oregon Legislative leadership appointed members to a Joint Committee on the Interstate Bridge. These actions demonstrate Oregon’s agreement that replacement of the Interstate 5 Bridge is vital. As is conveyed in this report, the program office is working to set this project up for success by working with key partners to build the foundation as we move forward toward project development. -

Columbia River I-5 Bridge Planning Inventory Report

Report to the Washington State Legislature Columbia River I-5 Bridge Planning Inventory December 2017 Columbia River I-5 Bridge Planning Inventory Errata The Columbia River I-5 Bridge Planning Inventory published to WSDOT’s website on December 1, 2017 contained the following errata. The items below have been corrected in versions downloaded or printed after January 10, 2018. Section 4, page 62: Corrects the parties to the tolling agreement between the States—the Washington State Transportation Commission and the Oregon Transportation Commission. Miscellaneous sections and pages: Minor grammatical corrections. Columbia River I-5 Bridge Planning Inventory | December 2017 Table of Contents Executive Summary. .1 Section 1: Introduction. .29 Legislative Background to this Report Purpose and Structure of this Report Significant Characteristics of the Project Area Prior Work Summary Section 2: Long-Range Planning . .35 Introduction Bi-State Transportation Committee Portland/Vancouver I-5 Transportation and Trade Partnership Task Force The Transition from Long-Range Planning to Project Development Section 3: Context and Constraints . 41 Introduction Guiding Principles: Vision and Values Statement & Statement of Purpose and Need Built and Natural Environment Navigation and Aviation Protected Species and Resources Traffic Conditions and Travel Demand Safety of Bridge and Highway Facilities Freight Mobility Mobility for Transit, Pedestrian and Bicycle Travel Section 4: Funding and Finance. 55 Introduction Funding and Finance Plan Evolution During -

White Salmon Interstate Bridge Replacement Project

3. AFFECTED ENVIRONMENT, ENVIRONMENTAL CONSEQUENCES, AND MITIGATION Chapter 3 looks at the beneficial and adverse impacts of the Project on transportation operations, environmental resources, and the community. Each section begins with a description of the existing conditions for a specific resource and then compares how the resource would be positively or negatively affected by the No Action Alternative, the Preferred Alternative EC-2, and Alternative EC-3. The study area for each resource is illustrated in the respective appendices. Mitigation measures to avoid, minimize, or mitigate adverse impacts that could result from the build alternatives are also identified for each resource. 3.1. TRAFFIC OPERATIONS The Hood River Bridge provides an essential interstate connection between Oregon and Washington. The existing bridge connects White Salmon, Washington, and Hood River, Oregon, and was used by over 4.5 million vehicles in a 1-year period spanning July 2017 to June 2018. A substantial majority of the total vehicles crossing the Hood River Bridge per year are passenger automobiles or light-duty pickups. These vehicles make up over 97 percent total vehicles on the bridge, while larger vehicles (trucks and other heavy vehicles) make up approximately 2 percent to 3 percent of total traffic. Traffic analysis for the Project included eight study intersections (Exhibit 3-1) and examined for two peak hours when traffic volumes were Large vehicles crossing the existing bridge are advised to highest during the morning (7:30 am to 8:30 am) and afternoon (4:00 pm turn in mirrors due to narrow lanes. to 5:00 pm). Exhibit 3-1. -

White Salmon Planning Commission Meeting AGENDA February 24, 2021

White Salmon Planning Commission Meeting AGENDA February 24, 2021 – 5:30 PM Via Zoom Teleconference Meeting ID: 840 1289 8223 Passcode: 623377 Call in Numbers: 669-900-6833 929-205-6099 301-715-8592 346-248-7799 253-215-8782 312-626-6799 We ask that the audience call in instead of videoing in or turn off your camera, so video does not show during the meeting to prevent disruption. Thank you. Call to Order/Roll Call Public Comment – Draft Elements 1. Public comment will not be taken during the teleconference. Public comment submitted by email to Jan Brending at [email protected] by 5:00 p.m. on Wednesday, February 24, 2021 will be read during the planning commission meeting and forwarded to all planning commissioners. Please include in the subject line "Public Comment - February 24, 2021 - Planning Commission Meeting." Please indicate whether you live in or outside of the city limits of White Salmon. Discussion Items 2. Presentation and Discussion of Draft Elements a. History and Historic Places b. Transportation c. Public Facilities and Services d. Capital Improvement Program 3. Comprehensive Plan Update Workshop a. Environmental Quality and Critical Areas Element b. Economics Element c. Parks and Recreation Element d. HIstory and Historic Places Element (if time allows) Adjournment 1 File Attachments for Item: 2. Presentation and Discussion of Draft Elements a. HIstory and HIstoric Places b. Transportation c. Public Facilities and Services d. Capital Improvement Program 2 II. HISTORY AND HISTORIC PLACES Background Context and History Environmental context The City of White Salmon lies in a transition zone between the maritime climate west of the Cascade Mountain Range and the dry continental climate of the inter-mountain region to the east. -

Corridor Plan

HOOD RIVER MT HOOD (OR HIGHWAY 35) Corridor Plan Oregon Department of Transportation DOR An Element of the HOOD RIVER-MT. HOOD (OR 35) CORRIDOR PLAN Oregon Department of Transportahon Prepared by: ODOT Region I David Evans and Associates,Inc. Cogan Owens Cogan October 1997 21 October, 1997 STAFF REPORT INTERIM CORRIDOR STRATEGY HOOD RIVER-MT. HOOD (OR HWY 35) CORRIDOR PLAN (INCLUDING HWY 281 AND HWY 282) Proposed Action Endorsement of the Hood River-Mt. Hood (OR HWY 35) Corridor Strategy. The Qregon Bep ent of Transportation (ODOT) has been working wi& Tribal and local governments, transportation service providers, interest groups, statewide agencies and stakeholder committees, and the general public to develop a long-term plan for the Hood River-Mt. Hood (OR HWY 35) Corridor. The Hood River-Mt. Hood Corridor Plan is a long-range (20-year) program for managing all transportation modes within the Oregon Highway 35 corridor from the 1-84 junction to the US 26 junction (see Corridor Map). The first phase of that process has resulted in the attached Interim Com'dor Stvategy. The Interim Corridor Strategy is a critical element of the Hood River- Mt. Hood Corridor Plan. The Corridor Strategy will guide development of the Corridor Plan and Refinement Plans for specific areas and issues within the corridor. Simultaneous with preparation of the Corridor Plan, Transportation System Plans (TSPs) are being prepared for the cities of Hood River and Cascade Locks and for Hood River County. ODOT is contributing staff and financial resources to these efforts, both to ensure coordination between the TSPs and the Corridor Plan and to avoid duplication of efforts, e.g. -

Soc 1-1 10.1 Socioeconomics Resource Study (Soc 1)

PacifiCorp/Cowlitz PUD Lewis River Hydroelectric Projects FERC Project Nos. 935, 2071, 2111, 2213 TABLE OF CONTENTS 10.0 SOCIOECONOMICS.................................................................................... SOC 1-1 10.1 SOCIOECONOMICS RESOURCE STUDY (SOC 1).......................... SOC 1-1 10.1.1 Study Objectives......................................................................... SOC 1-1 10.1.2 Study Area .................................................................................. SOC 1-2 10.1.3 Methods ...................................................................................... SOC 1-5 10.1.4 Key Questions............................................................................. SOC 1-7 10.1.5 Results......................................................................................... SOC 1-8 10.1.6 Discussion................................................................................. SOC 1-49 10.1.7 Schedule.................................................................................... SOC 1-51 10.1.8 References................................................................................. SOC 1-52 10.1.9 Comments and Responses on Draft Report .............................. SOC 1-57 SOC 1 Appendix 1 Text of RCW 54.28.050 SOC 1 Appendix 2 Descriptive Text of Money Generation Model LIST OF TABLES Table 10.1-1. Local sources of socioeconomic information...................................SOC 1-5 Table 10.1-2. 1990 population distribution by age in the secondary study area. ................................................................................................SOC -

Interstate 5 Columbia River Crossing Historic Built Environment Technical Report for the Final Environmental Impact Statement

I N T E R S TAT E 5 C O L U M B I A R I V E R C ROSSING Historic Built Environment Technical Report for the Final Environmental Impact Statement May 2011 Title VI The Columbia River Crossing project team ensures full compliance with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 by prohibiting discrimination against any person on the basis of race, color, national origin or sex in the provision of benefits and services resulting from its federally assisted programs and activities. For questions regarding WSDOT’s Title VI Program, you may contact the Department’s Title VI Coordinator at (360) 705-7098. For questions regarding ODOT’s Title VI Program, you may contact the Department’s Civil Rights Office at (503) 986-4350. Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) Information If you would like copies of this document in an alternative format, please call the Columbia River Crossing (CRC) project office at (360) 737-2726 or (503) 256-2726. Persons who are deaf or hard of hearing may contact the CRC project through the Telecommunications Relay Service by dialing 7-1-1. ¿Habla usted español? La informacion en esta publicación se puede traducir para usted. Para solicitar los servicios de traducción favor de llamar al (503) 731-4128. Interstate 5 Columbia River Crossing Historic Built Environment Technical Report for the Final Environmental Impact Statement This page intentionally left blank. May 2011 Interstate 5 Columbia River Crossing Historic Built Environment Technical Report for the Final Environmental Impact Statement Cover Sheet Interstate 5 Columbia River Crossing Historic Built Environment Technical Report for the Final Environmental Impact Statement: Submitted By: Derek Chisholm Mike Gallagher Rosalind Keeney Elisabeth Leaf Julie Osborne Saundra Powell Jessica Roberts Megan Taylor Parametrix May 2011 Interstate 5 Columbia River Crossing Historic Built Environment Technical Report for the Final Environmental Impact Statement This page intentionally left blank. -

(Interstate Tol1 Bridge) State Route 433 Spanning Langview Ca

LONGVIEW BRIDGE HAER No. WA-89 (Lewis & Clark Bridge) (Columbia River Bridge) (Interstate Tol1 Bridge) State Route 433 spanning the Columbia River Langview Cawlitz County Washington > WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA PHOTDBRAPHS HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERINS RECORD NATIONAL PARK SERVICE DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR P.O. BOX 37127 WASHINGTON, D.C. 20013-7127 r H*E£ HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD LONGVIEW BRIDGE (Lewis and Clark Bridge) I- * (Columbia River Bridge) (Interstate Toll Bridge) HAER No. WA-89 Location: State Route 433 spanning the Columbia River between Multnomah County, Oregon and Cowlitz County, Washington; beginning at milepost 0.00 on state route 433. UTM: 10/503650/5106420 10/502670/5104880 Quad: Rainier, Oreg.-Wash, Date of Construction: 1930 Engineer: Joseph B. Strauss, Strauss Engineering Corp., Chicago, IL Fabricator/Builder: Bethlehem Steel Company, Steelton, PA, general contractor Owner: 1927-1935: Columbia River—Longview Bridge Company. 1936-1947: Longview Bridge Company operated by Bethlehem Steel. 1947-1965: Washington Toll Bridge Authority. 1965 to present: Washington Department of Highways, since 1977, Washington State Department of Transportation, Olympia, Washington• Present Use: Vehicular and pedestrian traffic Significance: The Longview Bridge, designed by engineer Joseph B. Strauss, was at time of construction the longest cantilever span in North America with its 1,200' central section. Extreme vertical and horizontal shipping channel requirements requested by Portland, Oregon, as a means to prevent the bridge's construction created the reason for such an imposing structure. Historian: Robert W. Hadlow, Ph.D., August 1993 LONGVIEW BRIDGE • HAER No. WA-89 (Page 2) History of the Bridge The Longview Bridge was built as part of an entrepreneurial dream to make the city of Longviev a thriving Columbia River port city. -

Tribal Perspectives Teacher Guide

Teacher Guide for 7th – 12th Grades for use with the educational DVD Tribal Perspectives on American History in the Northwest First Edition The Regional Learning Project collaborates with tribal educators to produce top quality, primary resource materials about Native Americans and regional history. Teacher Guide prepared by Bob Boyer, Shana Brown, Kim Lugthart, Elizabeth Sperry, and Sally Thompson © 2008 Regional Learning Project, The University of Montana, Center for Continuing Education Regional Learning Project at the University of Montana–Missoula grants teachers permission to photocopy the activity pages from this book for classroom use. No other part of this publication may be reproduced in whole or in part, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission of the publisher. For more information regarding permission, write to Regional Learning Project, UM Continuing Education, Missoula, MT 59812. Acknowledgements Regional Learning Project extends grateful acknowledgement to the tribal representatives contributing to this project. The following is a list of those appearing in the DVD Tribal Perspectives on American History in the Northwest, from interviews conducted by Sally Thompson, Ph.D. Lewis Malatare (Yakama) Lee Bourgeau (Nez Perce) Allen Pinkham (Nez Perce) Julie Cajune (Salish) Pat Courtney Gold (Wasco) Maria Pascua (Makah) Armand Minthorn (Cayuse–Nez Perce) Cecelia Bearchum (Walla Walla–Yakama) Vernon Finley -

Interstate 5 Columbia River Crossing

I NTERSTATE 5 C OLUMBIA R IVER C ROSSING Neighborhoods and Population Technical Report May 2008 TO: Readers of the CRC Technical Reports FROM: CRC Project Team SUBJECT: Differences between CRC DEIS and Technical Reports The I-5 Columbia River Crossing (CRC) Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) presents information summarized from numerous technical documents. Most of these documents are discipline- specific technical reports (e.g., archeology, noise and vibration, navigation, etc.). These reports include a detailed explanation of the data gathering and analytical methods used by each discipline team. The methodologies were reviewed by federal, state and local agencies before analysis began. The technical reports are longer and more detailed than the DEIS and should be referred to for information beyond that which is presented in the DEIS. For example, findings summarized in the DEIS are supported by analysis in the technical reports and their appendices. The DEIS organizes the range of alternatives differently than the technical reports. Although the information contained in the DEIS was derived from the analyses documented in the technical reports, this information is organized differently in the DEIS than in the reports. The following explains these differences. The following details the significant differences between how alternatives are described, terminology, and how impacts are organized in the DEIS and in most technical reports so that readers of the DEIS can understand where to look for information in the technical reports. Some technical reports do not exhibit all these differences from the DEIS. Difference #1: Description of Alternatives The first difference readers of the technical reports are likely to discover is that the full alternatives are packaged differently than in the DEIS. -

Historic Columbia River Highway: Oral History August 2009 6

HHHIIISSSTTTOOORRRIIICCC CCCOOOLLLUUUMMMBBBIIIAAA RRRIIIVVVEEERRR HHHIIIGGGHHHWWWAAAYYY OOORRRAAALLL HHHIIISSSTTTOOORRRYYY FFFiiinnnaaalll RRReeepppooorrrttt SSSRRR 555000000---222666111 HISTORIC COLUMBIA RIVER HIGHWAY ORAL HISTORY Final Report SR 500-261 by Robert W. Hadlow, Ph.D., ODOT Senior Historian Amanda Joy Pietz, ODOT Research and Hannah Kullberg and Sara Morrissey, ODOT Interns Kristen Stallman, ODOT Scenic Area Coordinator Myra Sperley, ODOT Research Linda Dodds, Historian for Oregon Department of Transportation Research Section 200 Hawthorne Ave. SE, Suite B-240 Salem OR 97301-5192 August 2009 Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. OR-RD-10-03 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date Historic Columbia River Highway: Oral History August 2009 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Robert W. Hadlow, Ph.D., ODOT Senior Historian; Amanda Joy Pietz, ODOT Research; and Hannah Kullberg and Sara Morrissey, ODOT Interns ; Kristen Stallman, ODOT Scenic Area Coordinator; Myra Sperley, ODOT Research; and Linda Dodds, Historian 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) Oregon Department of Transportation Research Section 11. Contract or Grant No. 200 Hawthorne Ave. SE, Suite B-240 Salem, OR 97301-5192 SR 500-261 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered Oregon Department of Transportation Final Report Research Section 200 Hawthorne Ave. SE, Suite B-240 Salem, OR 97301-5192 14. Sponsoring Agency Code 15. Supplementary Notes 16. Abstract The Historic Columbia River Highway: Oral History Project compliments a larger effort in Oregon to reconnect abandoned sections of the Historic Columbia River Highway. -

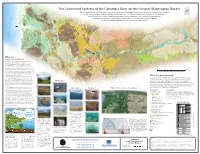

The Connected Systems of the Columbia River on the Oregon

The Connected Systems of the Columbia River on the Oregon-Washington Border WASHINGTON The Columbia River, in its 309-mile course along the Oregon-Washington border, provides a rich and varied environment OREGON for the people, wildlife, and plants living and interacting there. The area’s geology is the basis for the landscape and ecosystems we know today. By deepening our understanding of interactions of Earth systems — geosphere, hydrosphere, atmosphere, and biosphere — Earth science helps us manage our greatest challenges and make the most of vital opportunities. ⑮ ⑥ ④ ⑬ ⑧ ⑪ ① ⑦ ② ③ What is a ⑭ ⑫ ⑤ connected system? ⑩ A connected system is a set of interacting components that directly or indirectly influence one another. The Earth system has four major components. The geosphere includes the crust and the interior of the planet. It contains all of the rocky parts of the planet, the processes that cause them to form, and the processes that have caused ⑨ them to change during Earth’s history. The parts can be as small 0 10 20 40 Miles ∆ N as a mineral grain or as large as the ocean floor. Some processes act slowly, like the gradual wearing away of cliffs by a river. Geosphere Others are more dramatic, like the violent release of gases and magma during a volcanic eruption. ① What is a geologic map? The fluid spheres are the liquid and gas parts of the Earth system. The atmosphere includes the mixture of gases that Geologic maps show what kinds of rocks and structures make up a landscape. surrounds the Earth. The hydrosphere includes the planet’s The geologic makeup of an area can strongly influence the kinds of soils, water water system.