Historic Columbia River Highway: Oral History August 2009 6

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Oregon Administrative Rules Compilation

2019 OREGON ADMINISTRATIVE RULES COMPILATION CHAPTER 736 Parks and Recreation Department Published By DENNIS RICHARDSON Secretary of State Copyright 2019 Office of the Secretary of State Rules effective as of January 01, 2019 DIVISION 1 PROCEDURAL RULES 736-001-0000 Notice of Proposed Rules 736-001-0005 Model Rules of Procedure 736-001-0030 Fees for Public Records DIVISION 2 ADMINISTRATIVE ACTIVITIES 736-002-0010 State Park Cooperating Associations 736-002-0015 Working with Donor Organizations 736-002-0020 Criminal Records Checks 736-002-0030 Definitions 736-002-0038 Designated Positions: Authorized Designee and Contact Person 736-002-0042 Criminal Records Check Process 736-002-0050 Preliminary Fitness Determination. 736-002-0052 Hiring or Appointing on a Preliminary Basis 736-002-0058 Final Fitness Determination 736-002-0070 Crimes Considered 736-002-0102 Appealing a Fitness Determination 736-002-0150 Recordkeeping, Confidentiality, and Retention 736-002-0160 Fees DIVISION 3 WILLAMETTE RIVER GREENWAY PLAN 736-003-0005 Willamette River Greenway Plan DIVISION 4 DISTRIBUTION OF ALL-TERRAIN VEHICLE FUNDSTO PUBLIC AND PRIVATELY OWNED LANDMANAGERS, ATV CLUBS AND ORGANIZATIONS 736-004-0005 Purpose of Rule 736-004-0010 Statutory Authority 736-004-0015 Definitions 736-004-0020 ATV Grant Program: Apportionment of Monies 736-004-0025 Grant Application Eligibility and Requirements 736-004-0030 Project Administration 736-004-0035 Establishment of the ATV Advisory Committee 736-004-0045 ATV Operating Permit Agent Application and Privileges 736-004-0060 -

Oregon Historic Trails Report Book (1998)

i ,' o () (\ ô OnBcox HrsroRrc Tnans Rpponr ô o o o. o o o o (--) -,J arJ-- ö o {" , ã. |¡ t I o t o I I r- L L L L L (- Presented by the Oregon Trails Coordinating Council L , May,I998 U (- Compiled by Karen Bassett, Jim Renner, and Joyce White. Copyright @ 1998 Oregon Trails Coordinating Council Salem, Oregon All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America. Oregon Historic Trails Report Table of Contents Executive summary 1 Project history 3 Introduction to Oregon's Historic Trails 7 Oregon's National Historic Trails 11 Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail I3 Oregon National Historic Trail. 27 Applegate National Historic Trail .41 Nez Perce National Historic Trail .63 Oregon's Historic Trails 75 Klamath Trail, 19th Century 17 Jedediah Smith Route, 1828 81 Nathaniel Wyeth Route, t83211834 99 Benjamin Bonneville Route, 1 833/1 834 .. 115 Ewing Young Route, 1834/1837 .. t29 V/hitman Mission Route, 184l-1847 . .. t4t Upper Columbia River Route, 1841-1851 .. 167 John Fremont Route, 1843 .. 183 Meek Cutoff, 1845 .. 199 Cutoff to the Barlow Road, 1848-1884 217 Free Emigrant Road, 1853 225 Santiam Wagon Road, 1865-1939 233 General recommendations . 241 Product development guidelines 243 Acknowledgements 241 Lewis & Clark OREGON National Historic Trail, 1804-1806 I I t . .....¡.. ,r la RivaÌ ï L (t ¡ ...--."f Pðiräldton r,i " 'f Route description I (_-- tt |". -

Washington Division of Geology and Earth Resources Open File Report

RECONNAISSANCE SURFICIAL GEOLOGIC MAPPING OF THE LATE CENOZOIC SEDIMENTS OF THE COLUMBIA BASIN, WASHINGTON by James G. Rigby and Kurt Othberg with contributions from Newell Campbell Larry Hanson Eugene Kiver Dale Stradling Gary Webster Open File Report 79-3 September 1979 State of Washington Department of Natural Resources Division of Geology and Earth Resources Olympia, Washington CONTENTS Introduction Objectives Study Area Regional Setting 1 Mapping Procedure 4 Sample Collection 8 Description of Map Units 8 Pre-Miocene Rocks 8 Columbia River Basalt, Yakima Basalt Subgroup 9 Ellensburg Formation 9 Gravels of the Ancestral Columbia River 13 Ringold Formation 15 Thorp Gravel 17 Gravel of Terrace Remnants 19 Tieton Andesite 23 Palouse Formation and Other Loess Deposits 23 Glacial Deposits 25 Catastrophic Flood Deposits 28 Background and previous work 30 Description and interpretation of flood deposits 35 Distinctive geomorphic features 38 Terraces and other features of undetermined origin 40 Post-Pleistocene Deposits 43 Landslide Deposits 44 Alluvium 45 Alluvial Fan Deposits 45 Older Alluvial Fan Deposits 45 Colluvium 46 Sand Dunes 46 Mirna Mounds and Other Periglacial(?) Patterned Ground 47 Structural Geology 48 Southwest Quadrant 48 Toppenish Ridge 49 Ah tanum Ridge 52 Horse Heaven Hills 52 East Selah Fault 53 Northern Saddle Mountains and Smyrna Bench 54 Selah Butte Area 57 Miscellaneous Areas 58 Northwest Quadrant 58 Kittitas Valley 58 Beebe Terrace Disturbance 59 Winesap Lineament 60 Northeast Quadrant 60 Southeast Quadrant 61 Recommendations 62 Stratigraphy 62 Structure 63 Summary 64 References Cited 66 Appendix A - Tephrochronology and identification of collected datable materials 82 Appendix B - Description of field mapping units 88 Northeast Quadrant 89 Northwest Quadrant 90 Southwest Quadrant 91 Southeast Quadrant 92 ii ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 1. -

Summer 2019 Newsletter

Friends of the Columbia Gorge Protecting the Gorge Since 1980 Summer 2019 Newsletter How Much Love Is Too Much for the Gorge? Friends of the Columbia Gorge Board of Directors Greg Delwiche Chair Buck Parker* Vice Chair Kari Skedsvold Secretary/Treasurer Joe Campbell Anne Munch Geoff Carr John Nelson* Gwen Farnham Carrie Nobles Don Friedman Lisa Platt John Harrison Mia Prickett David Michalek* Cynthia Winter* Patty Mizutani Board of Trustees – Land Trust John Nelson* President David Michalek* Secretary/Treasurer John Baugher Hikers boarding a Skamania County Pat Campbell WET Bus at Dog Mountain trailhead. Geoff Carr Take Action Photo: Micheal Drewry Greg Delwiche Dustin Klinger Barbara Nelson Rick Ray* Land Trust Advisor The Columbia River Gorge Commission Address and mail your letter to: and U.S. Forest Service are currently Columbia River Gorge Commission Staff reviewing the National Scenic Area Sophia Aepfelbacher Membership Coordinator Management Plan. One of the priority #1 Town & Country Square Frances Ambrose* Land Trust Assistant topics is recreation, and whether new 57 NE Wauna Avenue Nathan Baker Senior Staff Attorney recreation policies need to be adopted. White Salmon, WA 98672 Mika Barrett Stewardship Volunteer Coord. Dan Bell* Land Trust Director You can submit a comment online at Elizabeth Brooke-Willbanks Development Manager Please send a letter to the Commission gorgecommission.org/about-crgc/ Peter Cornelison* Field Representative and advocate for sustainable recreation in Pam Davee Director of Philanthropy the Gorge. To learn more, see the feature contact. Questions? Contact Ryan Burt Edwards Communications Director article on page 4. Rittenhouse at [email protected]. Natalie Ferraro Trailhead Ambassador Coord. -

White Salmon Interstate Bridge Replacement Project

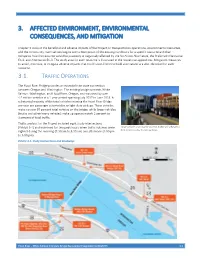

3. AFFECTED ENVIRONMENT, ENVIRONMENTAL CONSEQUENCES, AND MITIGATION Chapter 3 looks at the beneficial and adverse impacts of the Project on transportation operations, environmental resources, and the community. Each section begins with a description of the existing conditions for a specific resource and then compares how the resource would be positively or negatively affected by the No Action Alternative, the Preferred Alternative EC-2, and Alternative EC-3. The study area for each resource is illustrated in the respective appendices. Mitigation measures to avoid, minimize, or mitigate adverse impacts that could result from the build alternatives are also identified for each resource. 3.1. TRAFFIC OPERATIONS The Hood River Bridge provides an essential interstate connection between Oregon and Washington. The existing bridge connects White Salmon, Washington, and Hood River, Oregon, and was used by over 4.5 million vehicles in a 1-year period spanning July 2017 to June 2018. A substantial majority of the total vehicles crossing the Hood River Bridge per year are passenger automobiles or light-duty pickups. These vehicles make up over 97 percent total vehicles on the bridge, while larger vehicles (trucks and other heavy vehicles) make up approximately 2 percent to 3 percent of total traffic. Traffic analysis for the Project included eight study intersections (Exhibit 3-1) and examined for two peak hours when traffic volumes were Large vehicles crossing the existing bridge are advised to highest during the morning (7:30 am to 8:30 am) and afternoon (4:00 pm turn in mirrors due to narrow lanes. to 5:00 pm). Exhibit 3-1. -

Chapter 1 Introduction

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION Multnomah County CWPP 1 CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION Fires are a natural part of the forest ecosystem in Multnomah County, Oregon. In fact, they have shaped the forests valued by Multnomah County residents and visitors. However, decades of forest management, fire suppression and climate change have significantly altered forest composition and structure. The result is an increase in the wildfire hazard as forest vegetation has accumulated to create a more closed, tighter forest environment that tends to burn more intensely than in the past. Rising temperatures and changes to precipitation patters result in drought conditions, making forests more susceptible to ignitions. The exposure to wildfire hazards is also increasing, as recent population growth has spurred more residential development close to the forests in what is referred to as the wildland urban interface (WUI). As development encroaches upon forests with altered fire regimes that are more conducive to larger, more intense fires, the risk to life, property, and natural resources continues to escalate. The Multnomah County Community Wildfire Protection Plan (MCWPP) provides direction and helps facilitate a wildfire-based approach to managing our forestlands and the human development in the interface. In August, 2010, the Wildfire Planning Steering Committee was established to provide oversight and guidance for the development of the MCWPP. Membership included representation from the county’s Fire Defense Board and the public agencies responsible for natural resource management and fire protection. The Steering Committee actually began as the “Wildfire Technical Committee, “ established by Portland City Council in 2009 to implement the Action Plan of the City’s Wildfire Readiness Assessment: Gap Analysis Report (2009) 1 and manage future wildfire mitigation and fuels reduction projects associated with the Portland Natural Hazards Mitigation Plan. -

Our Tuesday and Thursday Series of Day Hikes and Rambles, Most Within Two Hours of Lake Oswego

Lake Oswego Parks & Recreation Hikes and Rambles Spring/Summer 2015 Calendar of Hikes/Rambles/Walks Welcome to our Tuesday and Thursday series of day hikes and rambles, most within two hours of Lake Oswego. Information is also available at LO Park & Rec Activities Catalog . To recieve weekly News email send your request to [email protected]. Hikes are for hikers of intermediate ability. Hiking distance is usually between 6 - 10 miles, and usually with an elevation gain/loss between 800 - 2000 ft. Longer hikes, greater elevation gains or unusual trail conditions will be noted in the hike description. Hikes leave at 8:00 a.m., unless otherwise indicated. Rambles are typically shorter, less rugged, and more leisurely paced -- perfect for beginners. Outings are usually 5-7 miles with comfortable elevation gains and good trail conditions. Leaves promptly at 8:30a unless otherwise noted. Meeting Places All hikes and rambles leave from the City of Lake Oswego West End Building (WEB), 4101 Kruse Way, Lake Oswego. Park in the lower parking lot (behind the building) off of Kruse Way. Individual hike or ramble descriptions may include second pickup times and places. (See included places table.) for legend. All mileages indicated are roundtrip. Second Meeting Places Code Meeting Place AWHD Airport Way Home Depot, Exit 24-B off I-205, SW corner of parking lot CFM Clackamas Fred Meyer, Exit 12-A off I-205, north lot near Elmer's End of the Oregon Trail Interpretative Center, Exit 10 off I-205, right on Washington Street to EOT parking lot by covered wagons Jantzen Beach Target,Exit 308 off I-5, left on N Hayden Island, left on N Parker, SE corner JBT Target parking lot L&C Lewis and Clark State Park. -

3.2 Flood Level of Risk* to Flooding Is a Common Occurrence in Northwest Oregon

PUBLIC COMMENT DRAFT 11/07/2016 3.2 Flood Level of Risk* to Flooding is a common occurrence in Northwest Oregon. All Flood Hazards jurisdictions in the Planning Area have rivers with high flood risk called Special Flood Hazard Areas (SFHA), except Wood High Village. Portions of the unincorporated area are particularly exposed to high flood risk from riverine flooding. •Unicorporated Multnomah County Developed areas in Gresham and Troutdale have moderate levels of risk to riverine flooding. Preliminary Flood Insurance Moderate Rate Maps (FIRMs) for the Sandy River developed by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) in 2016 •Gresham •Troutdale show significant additional risk to residents in Troutdale. Channel migration along the Sandy River poses risk to Low-Moderate hundreds of homes in Troutdale and unincorporated areas. •Fairview Some undeveloped areas of unincorporated Multnomah •Wood Village County are subject to urban flooding, but the impacts are low. Developed areas in the cities have a more moderate risk to Low urban flooding. •None Levee systems protect low-lying areas along the Columbia River, including thousands of residents and billions of dollars *Level of risk is based on the local OEM in assessed property. Though the probability of levee failure is Hazard Analysis scores determined by low, the impacts would be high for the Planning Area. each jurisdiction in the Planning Area. See Appendix C for more information Dam failure, though rare, can causing flooding in downstream on the methodology and scoring. communities in the Planning Area. Depending on the size of the dam, flooding can be localized or extreme and far-reaching. -

Hood River – White Salmon Interstate Bridge Replacement Project SDEIS

(OR SHPO Case No. 19-0587; WA DAHP Project Tracking Code: 2019-05-03456) Draft Historic Resources Technical Report October 1, 2020 Prepared for: Prepared by: In coordination with: 111 SW Columbia 851 SW Sixth Avenue Suite 1500 Suite 1600 Portland, Oregon 97201 Portland, Oregon 97204 This page intentionally left blank. TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................. 1 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 1 2. Project Alternatives ....................................................................................................................... 3 2.1. No Action Alternative .......................................................................................................... 7 2.2. Preferred Alternative EC-2 ................................................................................................... 8 2.3. Alternative EC-1 ................................................................................................................ 14 2.4. Alternative EC-3 ................................................................................................................ 19 2.5. Construction of the Build Alternatives ............................................................................... 23 3. Methodology .............................................................................................................................. -

Josephine County, Oregon, Historical Society Document Oregonłs

Finding fossils in Oregon is not so much a question of Places to see fossils: where to look for them as where not to look. Fossils are rare John Day Fossil Beds National Monument in the High Lava Plains and High Cascades, but even there, , _ Contains a 40-million year record of plant and animal life . ·� � .11�'!]�:-.: some of the lakes are famous for their fossils. Many of the ill the John Day Basill ill central Oregon near the towns of .• .� . ' · sedimentary rocks in eastern Oregon contain fossil leaves or · ,,����<:l. · . ' · •· Dayville' Fossil, and Mitchell. The Cant Ranch Visitor ; ' " ' ' j ' .- � bones. Leaffossils are especially abundant in the - Center at Sheep Rock on Highway 19 includes museum : ,· .,, 1 • , .. rocks at the far side of the athletic · exhibits of fossils. Open every day 8:30-5. For general l· · . ., ;: . · : field at Wheeler High School ,...,..;� information, contact John Day Fossil Beds National . -- - ' '· in the town of Fossil. Monument, 420 West Main St., John Day, OR 97845, ' l-, Although it is rare to phone (503) 575-0721. find a complete Oregon Museum of Science and Industry animal fossil, a 1945 SE Water Ave., Portland, OR 97214. Open Thurs. & search of river Fri. 9:30-9; Sat. through Wed. 9:30-7(sumrner hours); beds may turn . l 9:30-5(rest of year), phone (503) 797-4000 up c h1ps or Condon Museum, University of Oregon even teeth. In Pacific Hall, Eugene, OR 97403. Open only by western appointment, phone (503) 346-4577. Oregon, the ' . ; Douglas County Museum of History and sedimentary ' r Natural History rocks that are 1 primarily off1-5 at exit 123 at Roseburg (PO Box 1550, Roseburg, marine in OR 97470). -

Spring 2019 Newsletter

Friends of the Columbia Gorge Protecting the Gorge Since 1980 Spring 2019 Newsletter Spring Brings Hope for the Gorge Friends of the Columbia Gorge Oil train fire and oil spill in Mosier, Board of Directors Oregon, 2016. Geoff Carr Chair Photo: Paloma Ayala Debbie Asakawa Vice Chair Kari Skedsvold Secretary/Treasurer Pat Campbell Greg Delwiche John Nelson* Gwen Farnham Carrie Nobles Donald Friedman Buck Parker* John Harrison Lisa Berkson Platt David Michalek* Mia Prickett Patty Mizutani Vince Ready* Annie Munch Meredith Savery Land Trust Board of Trustees John Nelson* President David Michalek* Secretary/Treasurer John Baugher Land Trust Advisor Pat Campbell Greg Delwiche Take Action Dustin Klinger Barbara Nelson Buck Parker* Rick Ray* Protect Oregon from Dangerous Oil Trains Staff riends of the Columbia Gorge and proposed bills. Especially in light of Sophia Aepfelbacher Membership Coordinator Frances Ambrose* Land Trust Assistant our allies are supporting legislation the Trump administration’s repeal of a Nathan Baker Senior Staff Attorney in Oregon that would improve 2015 Department of Transportation rule Mika Barrett Stewardship Volunteer Coord. Fprotections against crude oil derailments and requiring oil trains to use newer, safer, Dan Bell* Land Trust Director Elizabeth Brooke-Willbanks Development Manager oil spills. House Bill 2858 and Senate Bill 99 breaking technology, Oregon needs to Peter Cornelison* Field Representative would require: ensure it is doing all it can to reduce the Pam Davee Director of Philanthropy threat from -

4. Lower Oregon Columbia Gorge Tributaries Watershed Assessment

4. Lower Oregon Columbia Gorge Tributaries Watershed Assessment 4.1 Subbasin Overview General Description Location and Size The Lower Oregon Columbia Gorge Tributaries Watershed consists of the 19 small Columbia River tributaries located between Bonneville Dam and the Hood River. Its major streams are Herman and Eagle creeks. The watershed is located in Hood River County, except for a small part of the Eagle Creek drainage, and includes the City of Cascade Locks and part of the City of Hood River. The watershed covers a drainage area of 63,714 acres or 99.6 square miles. Geology Volcanic lava flows, glaciers, and flooding were the key forces forming the Columbia Gorge landscape of basalt cliffs, waterfalls, talus slopes and ridges. Land elevations rise rapidly from 72 feet above sea level to approximately 5,000 feet. Mt. Defiance is the highest peak at 4,960 feet. Landslides are the dominant erosional process in recent history (USFS, 1998). Debris torrents and ice and snow avalanches are not uncommon in the winter months. Alluvial fan deposits at the mouths of the steeper, more constricted creeks suggest the frequent routing of debris torrents down these channels. The lower mile or so of creeks have gradients of about 5 percent, rising steeply at middle elevations, with lower gradient channels in glaciated headwater valleys. Climate and Weather The watershed lies in the transition zone between the wet marine climate to the west and the dry continental climate to the east. Precipitation amounts vary dramatically from east to west and with elevation, ranging from 40 to 125 to inches annually.