Multiple Appartenenze in the Autobiographical Macrotexts of Aldo Zargani and Clara Sereni’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Erenews 2020 3 1

ISSN 2531-6214 EREnews© vol. XVIII (2020) 3, 1-45 European Religious Education newsletter July - August - September 2020 Eventi, documenti, ricerche, pubblicazioni sulla gestione del fattore religioso nello spazio pubblico educativo e accademico in Europa ■ Un bollettino digitale trimestrale plurilingue ■ Editor: Flavio Pajer [email protected] EVENTS & DOCUMENTS EUROPEAN COURT OF HUMAN RIGHTS Guide on Art 2: Respect of parental rights, 2 CONSEIL DE L’EUROPE / CDH Une éducation sexuelle complète protège les enfants, 2 EUROPEAN COMMISSION Racial discrimination in education and EU equality law. Report 2020, 3 WCC-PCID Serving a wounded world in interreligious solidarity. A Christian call to reflection, 3 UNICEF-RELIGIONS FOR PEACE Launch of global multireligious Faith-in-Action Covid initiative, 3 OIEC Informe 2020 sobre la educacion catolica mundial en tiempos de crisis, 4 WORLD VALUES SURVEY ASSOCIATION European Values Study. Report 2917-2021, 4 USCIRF Releases new Report about conscientious objection, 4 PEW RESEARCH CENTER Between belief in God and morality: what connection? 4 AGENCY FOR FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS Fighting discrimination on grounds of religion and ethnicity 5 EUROPEAN WERGELAND CENTER 2019 Annual Report, 5 WORLD BANK GROUP / Education Global Practice Simulating the potential impacts of Covid, 5 AMERICAN ACADEMY OF RELIGION AAR Religious Literacy Guidelines, 2020, 6 CENTRE FOR MEDIA MONITORING APPG Religion in the Media inquiry into religious Literacy, 6 NATIONAL CHRONICLES DEUTSCHLAND / NSW Konfessionelle Kooperation in Religionsunterricht, -

Press Book Il Ghetto Di Venezia 31 Agosto

in accordo con TANGRAM FILM, ARSAM INTERNATIONAL E CERIGO FILMS PRESENTANO / PRESENT UN FILM DI / A FILM BY EMANUELA GIORDANO PROIEZIONE / SCREENING DOMENICA / SUNDAY 6 SETTEMBRE – CINEMA GIORGIONE – 18.30 Cannaregio 4612, Venezia UFFICIO STAMPA/PRESS OFFICE LINK DEL TRAILER / LINK TO THE TRAILER TANGRAM FILM http://www.jmtfilms.com/201353/History Cell/Mob: 3398397518 Email: [email protected] IL GHETTO DI VENEZIA, 500 ANNI DI VITA / THE VENICE GHETTO, 500 YEARS OF LIFE (Italia, Francia /Italy, France, HD, col. 55’) CAST TECNICO / CREDITS Regia / Director: Emanuela Giordano Con / with: Sandra Toffolatti, Laurence Olivieri Soggetto/ Original Story by: Alessandra Bonavina Sceneggiatura / Treatment: Emanuela Giordano, Alessandra Bonavina Script Editor: Isabella Aguilar Musiche Originali/ Original Music: Gilles Alonzo Fotografia / Cinematographer: Alberto Marchiori Montaggio / Editor: Sara Zavarise Illustratori/ Illustration: Felicita Sala, Gianluca Maruotti Animazione / Animation: Mathieu Rolin, Estelle Chaloupy, Marion Chopin Costumi / Costumes: Cristina Da Rold Scenografie / Set Designer: Mirko Donati Suono / Sound: Marco Zambrano Prodotto da / Produced by: Roberto Levi, Ilann Girard, Yannis Metzinger Una Produzione / A Production by: TANGRAM FILM in coproduzione con ARSAM INTERNATIONAL e CERIGO FILMS Distribuzione Italia / Italian Distribution: Cinecittà Istituto Luce Vendite Internazionali / World Sales: JMT Films Distribution Produttore esecutivo / Executive Producer: Carolina Levi Organizzazione / Production Manager for Tangram -

Trauma and Memory Four-Monthly European Review of Psychoanalysis and Social Science

Trauma and Memory Four-monthly European Review of Psychoanalysis and Social Science 2017, Volume 5, Number 2 (August) ISSN 2282-0043 http://www.eupsycho.com David Meghnagi, Ph.D., Editor-in-Chief Associate Editors Enzo Campelli (University of Rome, Rome) Jorge Canestri (International Psychoanalytic Association, Rome) Charles Hanly (International Psychoanalytic Association, University of Toronto) Claudia Hassan (University of Tor Vergata, Rome) Paolo Migone (Psicoterapia e Scienze Umane, Parma) Shalva Weill (Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem) Editorial Board Jacqueline Amati-Mehler (International Psychoanalytic Brunello Mantelli (University of Turin) Association, Rome) Marco Marchetti (International Psychoanalytic Association, Jolanta Ambrosewicz-Jacob (Jagiellonian University, University of Molise, Campobasso, Italy) Krakow) Giacomo Marramao (Roma Tre University, Rome) Marianna Bolko (Co-editor, Psicoterapia e Scienze Umane, Miriam Meghnagi (Clinical Psychologist, Musicologist, Bologna) Rome) Franco Borgogno (International Psychoanalytic Association, Alessandro Musetti (University of Parma) University of Turin) Adolfo Pazzagli (International Psychoanalytic Association, Toman Brod (Former Member, Czechoslovak Academy of University of Florence) Science, Praha) Andrea Peto (Central European University, Budapest) Castanon Garduno Victoria Elena (International Dina Porat (Yad Vashem, University of Tel Aviv) Psychoanalytic Association, University of Mexico) Filippo Pergola (IAD, University of Tor Vergata, Rome) Roberto Cipriani (Roma -

Italy and the Vatican

Italy and the Vatican National Affairs THEDEATH OF Pope John Paul II and the election of German- born Joseph Cardinal Ratzingeras his successor dominated the news. John Paul died April 2, aged 84, justover two months after falling ill with the flu. Ratzinger, 78, who had beena close aide and friend, was elected pope on April 19, taking the name Benedict XVI. Knownas a hard-line theologian, Ratzinger had served fortwo decades as the Vatican's doc- trinal watchdog in his capacityas head of the Congregation of the Doc- trine of the Faith. The papal transitionwas a worldwide media event and drew an unprecedented number of pilgrimsto Rome. Italian domestic politics centeredon preparations for the April 2006 general elections pitting Prime Minister SilvioBerlusconi's ruling center- right coalition against the center-leftopposition led by Romano Prodi,a former prime minister and former headof the European Commission. The center-left made sharp gains in regionalelections held in early April 2005. With voters in 13 of the country's 20regions going to the polls, the center-left rode to victory in 11 of them. Theresults prompted Berlus- coni to resign, reshuffle his cabinet, and forma new government. An opin- ion poll at the end of November indicatedthat Prodi's coalition would garner 52.7 percent of the vote against just 40.2percent for Berlusconi's bloc. But in December, Berlusconi'sallies pushed through a controver- sial electoral reform law that, accordingto the opposition, was intended tielp the center-right. The law restoreda completely proportional vot- system, replacing the mixed proportional and majoritysystem put in in 1994. -

Portrait of Italian Jewish Life (1800S – 1930S) Edited by Tullia Catalan, Cristiana Facchini Issue N

Portrait of Italian Jewish Life (1800s – 1930s) edited by Tullia Catalan, Cristiana Facchini Issue n. 8, November 2015 QUEST N. 8 - FOCUS QUEST. Issues in Contemporary Jewish History Journal of Fondazione CDEC Editors Michele Sarfatti (Fondazione CDEC, managing editor), Elissa Bemporad (Queens College of the City University of New York), Tullia Catalan (Università di Trieste), Cristiana Facchini (Università Alma Mater, Bologna; Max Weber Kolleg, Erfurt), Marcella Simoni (Università Ca’ Foscari, Venezia), Guri Schwarz (Università di Pisa), Ulrich Wyrwa (Zentrum für Antisemitismusforschung, Berlin). Editorial Assistant Laura Brazzo (Fondazione CDEC) Book Review Editor Dario Miccoli (Università Cà Foscari, Venezia) Editorial Advisory Board Ruth Ben Ghiat (New York University), Paolo Luca Bernardini (Università dell’Insubria), Dominique Bourel (Université de la Sorbonne, Paris), Michael Brenner (Ludwig-Maximilians Universität München), Enzo Campelli (Università La Sapienza di Roma), Francesco Cassata (Università di Genova), David Cesarani z.l. (Royal Holloway College, London), Roberto Della Rocca (DEC, Roma), Lois Dubin (Smith College, Northampton), Jacques Ehrenfreund (Université de Lausanne), Katherine E. Fleming (New York University), Anna Foa (Università La Sapienza di Roma), François Guesnet (University College London), Alessandro Guetta (INALCO, Paris), Stefano Jesurum (Corriere della Sera, Milano), András Kovács (Central European University, Budapest), Fabio Levi (Università degli Studi di Torino), Simon Levis Sullam (Università Ca’ -

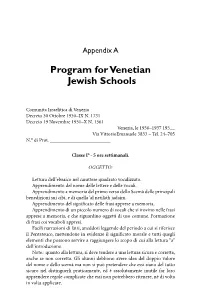

Program for Venetian Jewish Schools

Appendix A Program for Venetian Jewish Schools Comunita Israelitica di Venezia Decreto 30 Ottobre 1930–IX N. 1731 Decreto 19 Novembre 1931–X N. 1561 Venezia, le 1936–1937 193__ Via VittorioEmanuele 3833 – Tel. 24–705 N.° di Prot. ________________________ Classe I° - 5 ore settimanali. OGGETTO: Lettura dell’ebraico nel carattere quadrato vocalizzato. Apprendimento del nome delle lettere e delle vocali. Apprendimento a memoria del primo verso dello Scemà delle principali benedizioni sui cibi, e di quella ‘al netilàth jadaim. Apprendimento del significato delle frasi apprese a memoria. Apprendimento di un piccolo numero di vocali che si trovino nelle frasi apprese a memoria, e che riguardino oggetti di uso comune. Formazione di frasi coi vocaboli appresi. Facili narrazioni di fatti, aneddoti leggende del periodo a cui si riferisce il Pentateuco, mettendone in evidenze il significato morale e tutti quegli elementi che possono servire a raggiungere lo scopo di cui alla lettura “a” dell’introduzione. Note.: quanto alla lettura, si deve tendere a una lettura sicura e corretta, anche se non corretta. Gli alunni debbono avere idea del doppio valore del nome e dello scemà ma non si può pretendere che essi siano del tutto sicuro nel distinguerli praticamente, ed è assolutamente inutile far loro apprendere regole complicate che essi non potrebbero ritenere, nè di volta in volta applicare. 160 ITALIAN JEWS FROM EMANCIPATION TO THE RACIAL LAWS Classe II° - 5 ore settimanali. OGGETTO: Esercizi di lettura. Lettura spedita e corrente dello Scemà della ‘amidà dei giorni feriali. Scrittura ebraica corsiva. Apprendimento a memoria delle benedizioni relative alle principali mizvoth e cenni sui precetti a cui esse si riferiscono. -

A Shift in Jewish-Lutheran Relations? a Shift in Jewish-Lutheran Relations?

LWF Documentation DOC 48 A Shift in Jewish-Lutheran Relations? A Shift in Jewish-Lutheran Relations? The Lutheran World Federation 150, rte de Ferney CH-1211 Geneva 2 ISSN No. 0174-1756 Documentation No. 48/03 Switzerland ISBN No. 3-905676-00-1 The Lutheran World Federation LWF LWF A Shift in Jewish-Lutheran Relations? A Lutheran contribution to Christian-Jewish dialogue with a focus on antisemitism and anti-Judaism today Documentation No. 48 January 2003 Edited by Wolfgang Greive and Peter N. Prove on behalf of The Lutheran World Federation Department for Theology and Studies Office for Theology and the Church A Shift in Jewish-Lutheran Relations? LWF Documentation 48, January 2003 Editorial assistance: Iris J. Benesch Design: Stéphane Gallay, LWF-OCS Published by: The Lutheran World Federation 150, rte de Ferney P.O. Box 2100 CH-1211 Geneva 2 Switzerland © 2003, The Lutheran World Federation Printed in Switzerland by ATAR ROTO PRESSE S.A. ISSN 0174-1756 ISBN 3-905676-00-1 4 LWF Documentation No. 48 Contents Introduction 11 ........ A Long Road: Turning Points Wolfgang Greive 17 ........ Jews and Christians—Past, Present and the Prospects for the Future: The View of a Hungarian Jew Tamás Lichtmann Antimemitism and Anti-Judaism Today 25 ........ Antisemitism and Anti-Judaism Today: A Human Rights Perspective Peter N. Prove 29 ........ Antisemitism and the Struggle for Human Rights Jean Halpérin 33 ........ Some Reflections on the Theme Antisemitism and Anti-Judaism Hans Ucko Christology without Anti-Judaism? 41 ........ Anti-Judaism: A Core Problem of Christian Theology Leon Klenicki 69 ........ Anti-Judaism – A Problem for New Testament Theology: An Exegetical, Historical Perspective Wolfgang Kraus A Shift in Christian and Jewish Relations? 89 ....... -

2018 Italian Jewish Networks.Pdf

Italian Jewish Networks from the Seventeenth to the Twentieth Century Francesca Bregoli Carlotta Ferrara degli Uberti Guri Schwarz Editors Italian Jewish Networks from the Seventeenth to the Twentieth Century Bridging Europe and the Mediterranean Editors Francesca Bregoli Carlotta Ferrara degli Uberti Queens College and The Graduate University College London Center, CUNY London, UK New York, NY, USA Guri Schwarz University of Genova Genova, Italy ISBN 978-3-319-89404-1 ISBN 978-3-319-89405-8 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-89405-8 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018946702 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2018 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifcally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microflms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specifc statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

Zwanzig Jahre Lehrstuhl Für Jüdische Geschichte Und Kultur 1997 – 2017

Zwanzig Jahre Lehrstuhl für Jüdische Geschichte und Kultur an der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München 1997 – 2017 Das Team des Lehrstuhls für jü- dische Geschichte und Kultur an der LMU im Wandel der Zeit: 2006 oben rechts, 2009 oben links, 2014 mitte rechts, 2015 mitte links, unten im Jahr 2017 Inhalt Vorwort 4 Reflexionen 7 Wo sind ehemalige Mitarbeiter und Absolventen jetzt? 10 Zwanzig lehrreiche Jahre 12 Exkursionen 14 Europäische Sommeruniversität für Jüdische Studien 16 Jiddisch- und Hebräischlektorat 18 Drittmittelprojekte 19 Abgeschlossene Promotionen 20 Yerushalmi Lecture 22 Scholem Alejchem Vortrag 24 Gastvorträge 26 Wissenschaftliche Konferenzen 28 Allianz-Gastprofessur 34 Israel Institute-Gastprofessur 35 Mittelalterliche Jüdische Geschichte und Kultur 36 Zentrum für Israel-Studien 37 Jüdische Geschichte im Schulunterricht 40 Münchner Beiträge zur Jüdischen Geschichte und Kultur 41 Der Freundeskreis des Lehrstuhls 42 Zwanzig Jahre Lehrstuhl für Jüdische Geschichte und Kultur von Michael Brenner Was war? Der Lehrstuhl für Jüdische Geschichte und Kultur an der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität Es war symbolträchtig, dass die An- in München ist ein deutschlandweiter Nukleus nicht nur für Israel-Studien. International trittsvorlesung für den neuen Lehr- seit langem profiliert, stellt dessen Errichtung und interdisziplinäre Ausrichtung nach wie stuhl am 19. Juni 1997 in eben jener vor einen Meilenstein dar. Dabei ist der Lehrstuhl mit seinen zahlreichen öffentlichen Gast- vorträgen und internationalen Konferenzen auch aus der Münchner Kulturlandschaft nicht Großen Aula stattfand, in der am mehr wegzudenken. Dank dieser Tätigkeit werden die Landeshauptstadt und der ganze 19. November 1936 die „Forschungs- Freistaat zu einem international sichtbaren Ort für das Erinnern, Erforschen und Diskutie- abteilung Judenfrage“ im Reichs- ren jüdischer Geschichte und Kultur. -

Gang an Der Hfjs DISSERTATIONS

DASMussaf MAGAZIN DER HOCHSCHULE FÜR JÜDISCHE STUDIEN HEIDELBERG 1/2012 MUSEOLOGIE: Ein neuer Studien- gang an der HfJS DISSERTATIONS- PROJEKT: Italienische Wissen- schaft des Judentums ANTRITTS- VORLESUNG: Frederek Musall über maimonidisches Denken INHALT 16 20 23 Désirée Martin, Christin Zühlke FOTOS: Das Heidelberger Modell: plurale Strukturen, vielseitige Angebote 3 EDITORIAL 14 LEHRE UND FORSCHUNG 14 Dissertationsprojekt: Francesca Paolin über die italienische 5 TSCHICK TSCHAK: Wissenschaft des Judentums Neues aus der Hochschule auf einen Blick 16 levinas-tagung – ein Bericht von Silvia richter 18 Antrittsvorlesung von Frederek Musall: 6 AUS DER HOCHSCHULE „Es wird anstrengend“ 6 Hochschulreden: Joachim Gauck über Freiheit 20 Ausleihen statt kaufen: Empfehlungen aus der Bibliothek 8 „Für den rest des lebens“: der neue roman von Zeruya Shalev 21 UNSERE ABSOLVENTEN ... auf einen Blick. Auf der großen Deutschlandkarte. 10 STUDIUM 10 Der Ben gurion-lehrstuhl und die europäische Moderne – 22 STUDIERENDENVERTRETUNG ein Bericht von Omar Kamil 12 Museologie: ein neuer Studiengang stellt sich vor 23 VERANSTALTUNGSKALENDER/IMPRESSUM TITELBILD Innenansicht des Hauptraums der Synagoge, der Männerschul, in Schnaittach gegen Osten, © Jüdisches Museum Franken, Fotograf: Dieter Kachelrieß, Nürnberg, 1996 mit Blick auf den Toraschrein EDITORIAL ETWAS ZUR JÜDISCH- THEOLOGISCHEN FAKULTÄT Liebe Leserinnen, liebe Leser, ühlke Z Wie stets könnte dieses Editorial Die Entwicklung der Jahrzehnte seit der Shoa, der Neuan- hristin C sich damit begnügen, die Erfolge, fang nach der Liquidation der jüdischen Bildungseinrichtun- Akzente und Perspektiven unse- gen und der Vertreibung und Ermordung ihrer Angehörigen Judith Weißbach rer Hochschule anzureißen. Die in der Zeit des Nationalsozialismus, verlief in Deutschland mit Désirée Martin, gibt es ja auch diesmal – die fol- auffallenden Ähnlichkeiten zur Situation vor 1933: Während FOTO: genden Seiten sind Beleg. -

The Revisionist Clarion Oooooooooooooooooooooooooo

THE REVISIONIST CLARION OOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOO QUARTERLY NEWSLETTER ABOUT HISTORICAL REVISIONISM AND THE CRISIS OF IMPERIAL POWERS oooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooo TOWARDS THE DESTRUCTION OF ISRAEL AND THE ROLLING BACK OF USA ooooooooooooooooo Issue Nr. 22 Fall 2006 & Winter 2007 <revclar -at- yahoo.com.au> < http://revurevi.net > alternative archives http://vho.org/aaargh/engl/engl.html http://aaargh.com.mx/engl/engl.html ooooooooooooooooooooooooooooo CONTENTS THE BURDEN OF JERUSALEM by Rudyard Kipling THE TEHRAN CONFERENCE REVIEW OF HOLOCAUST : GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE See reviews, accounts, comments in our special issue of Conseils de révision < http://revurevi.net > Mystery of Israel's secret uranium bomb Alarm over radioactive legacy left by attack on Lebanon, Robert Fisk Gaza doctors say patients suffering mystery injuries after Israeli attacks Rory McCarthy Yes, It's the Lobby: "Political Fear" Drives US Support for Israel, James Abourezk A TUG-OF-WAR BETWEEN IRAN AND THE US/ISRAEL Adrian Salbuchi TEHERAN AND THE POLITICS OF THE HOLOCAUST Pierre Vidal-Naquet wants to strangle, crush, kill Faurisson, Robert Faurisson French academic again convicted for Holocaust denial French "holocaust" myth denier convicted for giving interview to Iran's TV The Influence of a Man Who Denies the Holocaust By Steven Stalinsky Succession of scandals leaves Olmert fighting to stay in power By Eric Silver Report about the Zundel Hearing October 4, 2006 by Ingrid Rumland The Power of Israel in the United States By Stephen Lendman The Big Lie About 'Islamic -

Trauma and Memory Four-Monthly European Review of Psychoanalysis and Social Science

Trauma and Memory Four-monthly European Review of Psychoanalysis and Social Science 2017, Volume 5, Number 1 (April) ISSN 2282-0043 http://www.eupsycho.com David Meghnagi, Ph.D., Editor-in-Chief Associate Editors Enzo Campelli (University of Rome, Rome) Jorge Canestri (International Psychoanalytic Association, Rome) Charles Hanly (International Psychoanalytic Association, University of Toronto) Claudia Hassan (University of Tor Vergata, Rome) Paolo Migone (Psicoterapia e Scienze Umane, Parma) Shalva Weill (Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem) Editorial Board Jacqueline Amati-Mehler (International Psychoanalytic Brunello Mantelli (University of Turin) Association, Rome) Marco Marchetti (International Psychoanalytic Association, Jolanta Ambrosewicz-Jacob (Jagiellonian University, University of Molise, Campobasso, Italy) Krakow) Giacomo Marramao (Roma Tre University, Rome) Marianna Bolko (Co-editor, Psicoterapia e Scienze Umane, Miriam Meghnagi (Clinical Psychologist, Musicologist, Bologna) Rome) Franco Borgogno (International Psychoanalytic Association, Alessandro Musetti (University of Parma) University of Turin) Adolfo Pazzagli (International Psychoanalytic Association, Toman Brod (Former Member, Czechoslovak Academy of University of Florence) Science, Praha) Andrea Peto (Central European University, Budapest) Castanon Garduno Victoria Elena (International Dina Porat (Yad Vashem, University of Tel Aviv) Psychoanalytic Association, University of Mexico) Filippo Pergola (IAD, University of Tor Vergata, Rome) Roberto Cipriani (Roma