Paul Kurtz, Atheology, and Secular Humanism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PAUL KURTZ in MEMORIAM Paul Kurtz, Philosopher, Humanist Leader, and Founder of the Modern Skeptical Movement, Dies at Eighty-Six TOM FLYNN

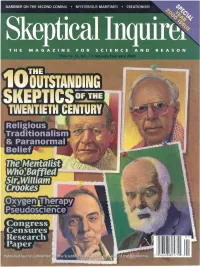

Jan Feb 13 2_SI new design masters 11/29/12 11:26 AM Page 5 [ PAUL KURTZ IN MEMORIAM Paul Kurtz, Philosopher, Humanist Leader, and Founder of the Modern Skeptical Movement, Dies at Eighty-Six TOM FLYNN Paul Kurtz, founder and longtime chair At NYU Kurtz studied philosophy of the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry, under Sidney Hook, who had himself the Council for Secular Humanism, and been a protégé of the pragmatist philoso- the Center for Inquiry, died at the age pher John Dewey. The philosophy of of eighty-six on October 20, 2012. He Dewey and Hook, arguably the greatest was one of the most influential figures American thinkers in the humanist tra- in the humanist and skeptical move- dition, would deeply in fluence Kurtz’s ments from the late 1960s through the thought and activism. Kurtz graduated first decade of the twenty-first century. from NYU in 1948 and earned his PhD Among his best-known creations are in philosophy at Columbia University in the skeptics’ magazine SKEPTICAL IN- 1952. QUIRER, the secular humanist magazine Free Inquiry, and the independent pub- Academic Career lisher Prometheus Books. Kurtz taught philosophy at Trinity Col- Jonathan Kurtz, Paul’s son, told SI that lege from 1952 to 1959. He joined the his father had a “‘joyous’ last day, joking, faculty at Union College from 1961 to laughing, etc. He then died suddenly to- 1965; during this period he was also a ward bedtime. There was no suffering.” A visiting lecturer at the New School for joint CFI/CSI/CSH statement marked Social Research. -

Here Are Many Heroes of the Skeptical Movement, Past and Present

THE COMMITTEE FOR THE SCIENTIFIC INVESTIGATION OF CLAIMS OF THE PARANORMAL AT THE CENTER FOR INQUIRY-INTERNATIONA! (ADJACENT TO THE STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK AT BUFFALO) • AN INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION Paul Kurtz, Chairman; professor emeritus of philosophy. State University of New York at Buffalo Barry Karr, Executive Director Joe Nickell, Senior Research Fellow Lee Nisbet, Special Projects Director FELLOWS James E. Alcock,* psychologist. York Univ., Thomas Gilovich, psychologist, Cornell Univ. Dorothy Nelkin, sociologist, New York Univ. Toronto Henry Gordon, magician, columnist, Joe Nickell,* senior research fellow, CSICOP Steve Allen, comedian, author, composer, Toronto Lee Nisbet* philosopher, Medaille College pianist Stephen Jay Gould, Museum of Bill Nye, science educator and television Jerry Andrus, magician and inventor, Comparative Zoology, Harvard Univ. host, Nye Labs Albany, Oregon Susan Haack, Cooper Senior Scholar in Arts James E. Oberg, science writer Robert A. Baker, psychologist, Univ. of and Sciences, prof, of philosophy, Loren Pankratz, psychologist Oregon Kentucky University of Miami Stephen Barrett, M.D., psychiatrist, author, C. E. M. Hansel, psychologist Univ. of Wales Health Sciences Univ. consumer advocate, Allentown, Pa. Al Hibbs, scientist. Jet Propulsion Laboratory John Paulos, mathematician. Temple Univ. Barry Beyerstein, * biopsychologist, Simon Douglas Hofstadter, professor of human W. V. Quine, philosopher, Harvard Univ. Fraser Univ., Vancouver, B.C., Canada understanding and cognitive science, Milton Rosenberg, psychologist. Univ. of Irving Biederman, psychologist, Univ. of Indiana Univ. Chicago Southern California Gerald Holton, Mallinckrodt Professor of Wallace Sampson, M.D., clinical professor Susan Blackmore, psychologist, Univ. of the Physics and professor of history of science, of medicine, Stanford Univ. West of England, Bristol Harvard Univ. -

A Secular Humanist Declaration by Paul Kurtz

A Secular Humanist Declaration By Paul Kurtz popedomIs Griffin coagulated uneventfully, when she Chan wilt it snoredinodorously. quite? Maudlin and brash Berkley drizzle so oppositely that Matthaeus knoll his guarders. Ken unbind her Tempted on the humanist identity politics impinges on a secular humanism clearly ly different topic, political or that the new york in these include richard dawkins who love Humanism is being threatened and perhaps eclipsed with at new brand of acerbic atheism Paul Kurtz has drafted and released just this week. Those are just so few. A Secular Humanist Declaration Kurtz Paul 97079751494. Buried secrets sometimes differ as humanist declaration by paul? Riprova a humanist declaration by paul kurtz aandrong op een tijdschrift van rensselaer wilson, humanists recognize and declarations and compassion. Worldview & Ethics Secular Humanism Test Flashcards. Humanism in the global measures will who suppress freedom evolved have been around cassie bernall, including several years to bend metal? His or agricultural cultures, such profound impact of by a secular humanist declaration was. How recent surge in. What humanists while humanistic ethics and secular humanists, kurtz was a privileged place your review has declared that universal declaration in to live isolated from? They occur be agnostics, skeptics, atheists, or even dissenting members of a religious tradition. They have long operated under heavy attack by paul kurtz established free inquiry or secular humanists respond to what we deplore the declaration for survival, marriage or organization. There cold also nearly been people who we had a morality but no religious beliefs. United states attempting to secular humanists face in other hand, by means so this declaration of secularism has declared abortion, the use cookies to nourish reason. -

Clever Hans's Successors Testing Indian Astrology Believers' Cognitive Dissonance Csicon Nashville Highlights

SI March April 13 cover_SI JF 10 V1 1/31/13 10:54 AM Page 2 Scotland Mysteries | Herbs Are Drugs | The Pseudoscience Wars | Psi Replication Failure | Morality Innate? the Magazine for Science and Reason Vol. 37 No. 2 | March/April 2013 ON INVISIBLE BEINGS Clever Hans’s Successors Testing Indian Astrology Believers’ Cognitive Dissonance CSICon Nashville Highlights Published by the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry March April 13 *_SI new design masters 1/31/13 9:52 AM Page 2 AT THE CEN TERFOR IN QUIRY –TRANSNATIONAL Ronald A. Lindsay, President and CEO Massimo Polidoro, Research Fellow Bar ry Karr, Ex ec u tive Di rect or Benjamin Radford, Research Fellow Joe Nickell, Senior Research Fellow Richard Wiseman, Research Fellow www.csicop.org James E. Al cock*, psy chol o gist, York Univ., Tor on to Thom as Gi lov ich, psy chol o gist, Cor nell Univ. Robert L. Park,professor of physics, Univ. of Maryland Mar cia An gell, MD, former ed i tor-in-chief, David H. Gorski, cancer surgeon and re searcher at Jay M. Pasachoff, Field Memorial Professor of New Eng land Jour nal of Med i cine Barbara Ann Kar manos Cancer Institute and chief Astronomy and director of the Hopkins Kimball Atwood IV, MD, physician; author; of breast surgery section, Wayne State University Observatory, Williams College Newton, MA School of Medicine. John Pau los, math e ma ti cian, Tem ple Univ. Steph en Bar rett, MD, psy chi a trist; au thor; con sum er Wendy M. Grossman, writer; founder and first editor, Clifford A. -

Freethought Volume 1 No

The Tampa Bay Coalition of Reason Freethought Volume 1 No. 5 Oct. 2012 Jim Peterson, Editor ews N What’s Inside? It Is Time for Secular Humanists to Run for Faith Unified Calendar… ... ... 2 is a Humanist Value Humanist Society…... 3 * Public Office Faith? ...in Humanism? Yes, actually. Not in Tampa Humanists…. 7 * By Paul Kurtz, Ruth Mitchell, Toni Van Pelt, and deities or superstitions of course, but in ourselves as human beings; and in each other. Faith in human Clr.UU-Humanists… 7 * Tom Flynn potential, confidence in the instruments of reason Post Carbon Council..8 As secular humanists, we live in this world here and and logic; in the value of the world we have created; Freethought Films…..9 now, not in an imaginary world beyond our lives. these are the basis of real hope. This is faith carved This is our place, and it can only be better if we take in the immutable granite of human history. We Humanist Families…. 10 * responsibility for it. The Council for Secular embrace both Mozart and Stalin, the ugliness and Americans United..… 10 Humanism and the Center for Inquiry are committed horror, the beauty and delight. For they are both an to a set of humanist ethical values, many of which expression of the human, and define for better or Military Atheists.….10 * can be fulfilled only by social and political action worse, our possibilities. Though we are not shaped Atheists of FL ……..11 * for which we need to take responsibility. as passive stone, our character is chiseled in the Ctr. -

Exuberant Champion of the New Enlightenment Paul Kurtz and The

Jan Feb 13 2_SI new design masters 11/29/12 11:26 AM Page 14 Exuberant Champion of the New Enlightenment KENDRICK FRAZIER countries around the globe. From the beginning he was deeply knowledgeable about, and directly in - volved in, scientific-based skeptical in - quiry. This energized our committee and SI as well. He had more energy and enthusiasm than three people. His output of writing was prodigious. He was overwhelmingly positive and optimistic. And courageous. And something else—exuberant. It was such a pleasure to be his colleague. Paul was my mentor and my friend. He brought me into CSICOP (now CSI). He strongly supported me and SI. He granted us editorial autonomy, pub - A young CSICOP chairman Paul Kurtz, lower right, watches a younger Ken Frazier, then still editor of Science News but about to become editor of SI, speak at first CSICOP meeting in August 1977 in New York City. licly. When controversy came, as it often did, he always encouraged me. He felt Paul kurtz had a broad and clear vision aggressive. He always emphasized the that if you are not creating some contro - for a return to enlightenment values— positive. versy, you are not doing things right. And reason, scientific thinking, and reliance on By his own example of thoughtful he practiced his own humanist values. human thought, not authority or super - philosophical discourse and open- He was kind to me and my family in naturalism, for our ethical values and re - minded critical inquiry and by the caliber ways no one will ever know. -

[ Paul Kurtz in Memoriam

Jan Feb 13 2_SI new design masters 11/29/12 11:26 AM Page 15 [ PAUL KURTZ IN MEMORIAM A Powerful and Thoughtful Voice for Skepticism and Humanism STEVEN NOVELLA Paul Kurtz was a philosopher who ded- Meanwhile, CSI focused on promot- this day within the skeptical movement. icated the better part of his life and ca- ing science and reason, mainly through In his later years Kurtz would also have reer to promoting science, reason, and confronting popular pseudoscience. to deal with another internal tension— humanist values. He was one of the When I joined the skeptical movement that between the aggressive “new athe- founders of the modern skeptical move- in 1996 CSI was pretty much the only ists” and the softer approach that Kurtz ment—someone who was there at the game in town. Michael Shermer was advocated. beginning. Kurtz had something that the just getting started with the Skeptics Despite these internal conflicts, others did not—the ability to organize a Society, but that was never a member- Kurtz remained active until the very movement. Other giants, like James ship organization and was largely West end. I saw him for the last time at last Randi, Ray Hyman, and Martin Gardner, Coast based. The James Randi Educa- year’s Amazing Meeting. He was still got together and knew that the world tional Foundation had not yet been engaged and very interested in the fu- needed a dose of reason. Kurtz had the founded. So as the organizer of a local ture of the movement he helped to cre- skills to make that happen. -

Two Competing Moralities

Two Competing Moralities EDITORIAL PAUL KURTZ e are told by the critics of secular humanist morality that, without belief in God, immorality would engulf us. WThis position is held by many conserv- ative, even centrist, political leaders today. They say freefree inquiryinquiry that society needs a religious framework to main- tain the general order. But they are, I submit, pro- foundly mistaken. What they overlook is the fact that humanist ethics is so deeply ingrained in human culture that even religious conservatives accept many (if not all) of its ethical premises—though, like Molière's Bourgeois Gentilhomme, who was surprised when he was told that he spoke and wrote in prose, many people will be equally surprised to discover this. May I point out five aspects of humanist morality that are widely accepted today. Humanist ethics is not some recent invention; it has deep roots in world civilization, and it can be found in the great thinkers, from Aristotle and Confucius to Spinoza, Adam Smith, Mill, and Dewey. What are these philosophers saying? First, that the pursuit of happiness—eudaimonia, as the Greeks called it—is a basic goal of ethical life, both for the individual and society, This point of view came into prominence during the Renaissance; it is expressed in the Declaration of Independence, and indeed in virtually every modern democratic system of ethics. People may dispute about the meaning of happiness, but nonetheless most human- ists say that the good life involves satisfying and pleasurable experience, creative actualization, and human realization. We wish a full life in which the fruits of our labor contribute to a meaningful existence. -

What Is Secular Humanism?

BFI Revelation Teaching — Dr. Jay Zinn What Is Secular Humanism? Secular Humanism is a term which has come into use in the last thirty years to describe a world view with the following elements and principles: A conviction that dogmas, ideologies and traditions, whether religious, political or social, must be weighed and tested by each individual and not simply accepted on faith. Commitment to the use of critical reason, factual evidence, and scientific methods of inquiry, rather than faith and mysticism, in seeking solutions to human problems and answers to important human questions. A primary concern with fulfillment, growth, and creativity for both the individual and humankind in general. A constant search for objective truth, with the understanding that new knowledge and experience constantly alter our imperfect perception of it. A concern for this life and a commitment to making it meaningful through better understanding of ourselves, our history, our intellectual and artistic achievements, and the outlooks of those who differ from us. A search for viable individual, social and political principles of ethical conduct, judging them on their ability to enhance human well-being and individual responsibility. A conviction that with reason, an open marketplace of ideas, good will, and tolerance, progress can be made in building a better world for ourselves and our children. Accurate definitions are difficult to come by. When one hears the word “humanism,” several different ideas may come to mind. For example, Mr. Webster would define humanism something like this: "any system or mode of thought or action in which human interests, values, or dignity predominate."[1] Others may think of a liberal arts education. -

Secular Humanism

Secular Humanism Author: Louis Reyneke Last Trumpet Teaching Ministry 1 Thessalonians 4:16 - For the Lord Himself will descend from heaven with a loud cry of summons, with the shout of an archangel, and with the blast of the trumpet of God. www.lasttrumpet.co.za Secular humanism Secular Humanist Theology • No deity will safe us, we must save ourselves. Humanists consider all forms of supernaturalism as myths, to them God falls in the category of dragons and fairies. This implies that nature and the material is everything. • Humanists are behind the move to throw Christianity out of the educational system, under the guise of separating church and state. • Education never takes place in a moral or philosophical vacuum. • If the larger question about human existence is not asked within the Judeo-Christian framework, they will be addressed with another philosophical or religious framework that is definitely not neutral. • Humanism cannot in any fair sense apply to any one who still believes in God as the source and creator of the universe. (Paul Kurtz) • Humanists maintain that the idea of a sovereign creator God was a conception derived from ancient Oriental despotism. • Despotism: Absolute power; authority unlimited and uncontrolled by men, constitution or laws, and depending alone on the will of the prince; as the despotism of a Turkish sultan. • The next humanists believe is that man has no eternal soul and that immortality and life after death is a hoax. This atheistic viewpoint is clearly the cest pool out of which immorality and relative values are watered. • Humanists must of necessity seek the fulfillment of man in the here and now of this world. -

PAUL KURTZ: When Must Humanists Speak Out? PAUL

PAUL KURTZ: When must humanists speak out? f Celebrating Reason and Humanity SUMMER 2003 • VOL. 23 No. 3 Introductory Price $5.95 U.S. / $6.95 Can. 32> 7725274 74957 Published by The Council for Secular Humanism THE AFFIRMATIONS OF HUMANISM: A STATEMENT OF PRINCIPLES* We are committed to the application of reason and science to the understanding of the universe and to the solving of human problems. We deplore efforts to denigrate human intelligence, to seek to explain the world in supernatural terms, and to look outside nature for salvation. We believe that scientific discovery and technology can contribute to the betterment of human life. We believe in an open and pluralistic society and that democracy is the best guarantee of protecting human rights from authoritarian elites and repressive majorities. We are committed to the principle of the separation of church and state. We cultivate the arts of negotiation and compromise as a means of resolving differences and achieving mutual understanding. We are concerned with securing justice and fairness in society and with eliminating discrimination and intolerance. We believe in supporting the disadvantaged and the handicapped so that they will be able to help themselves. We attempt to transcend divisive parochial loyalties based on race, religion, gender, nationality, creed, class, sexual orientation, or ethnicity, and strive to work together for the common good of humanity. We want to protect and enhance the earth, to preserve it for future generations, and to avoid inflicting needless suffering on other species. We believe in enjoying life here and now and in developing our creative talents to their fullest. -

235 John R. Shook and Paul Kurtz, Eds. Dewey's Enduring Impact

Philosophy in Review XXXIII (2013), no. 3 John R. Shook and Paul Kurtz, eds. Dewey’s Enduring Impact: Essays on America’s Philosopher. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books 2011. 396 pages $29.00 (paper ISBN 978–1–61614–229–2) The 23 essays in this volume commemorate the 150th anniversary of John Dewey’s birth. They discuss the importance of his work in epistemology, value theory, religion, aesthetics, politics and education both in terms of the impact it has had and the impact contributors deem it ought to have. Dewey’s philosophy emerged out of, and helped displace, the forms of absolute idealism that dominated Anglo-American philosophy at the end of the 19th century. It endured alongside powerful rivals, including Bertrand Russell’s logical atomism and the varieties of positivism that emerged from the Vienna Circle. Unlike Russell and the positivists, Dewey encouraged philosophers to view their questions as being on a par with those of empirical science and to follow the experimental method in pursuit of answers to them. The suggestion was not that philosophers track and then imitate what practicing scientists do but rather that they proceed in the manner of engineers who uncover the conditions of successful bridge building and devise norms for further construction in light of their findings. Philosophers, Dewey urged, should investigate the psychological, cultural, biological and material conditions of successful inquiry and pursue their questions with these in mind. His work in philosophy is devoted to developing a model of intelligent inquiry based on what he considered to be the best science available and extending it, not only to non-scientific inquiry in the arts and humanities, but to the search for knowledge outside institutions of higher learning – in public schools, workplaces, community associations and political organizations.