The Faith Dimension of Humanism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HUMANISM Religious Practices

HUMANISM Religious Practices . Required Daily Observances . Required Weekly Observances . Required Occasional Observances/Holy Days Religious Items . Personal Religious Items . Congregate Religious Items . Searches Requirements for Membership . Requirements (Includes Rites of Conversion) . Total Membership Medical Prohibitions Dietary Standards Burial Rituals . Death . Autopsies . Mourning Practices Sacred Writings Organizational Structure . Headquarters Location . Contact Office/Person History Theology 1 Religious Practices Required Daily Observance No required daily observances. Required Weekly Observance No required weekly observances, but many Humanists find fulfillment in congregating with other Humanists on a weekly basis (especially those who characterize themselves as Religious Humanists) or other regular basis for social and intellectual engagement, discussions, book talks, lectures, and similar activities. Required Occasional Observances No required occasional observances, but some Humanists (especially those who characterize themselves as Religious Humanists) celebrate life-cycle events with baby naming, coming of age, and marriage ceremonies as well as memorial services. Even though there are no required observances, there are several days throughout the calendar year that many Humanists consider holidays. They include (but are not limited to) the following: February 12. Darwin Day: This marks the birthday of Charles Darwin, whose research and findings in the field of biology, particularly his theory of evolution by natural selection, represent a breakthrough in human knowledge that Humanists celebrate. First Thursday in May. National Day of Reason: This day acknowledges the importance of reason, as opposed to blind faith, as the best method for determining valid conclusions. June 21 - Summer Solstice. This day is also known as World Humanist Day and is a celebration of the longest day of the year. -

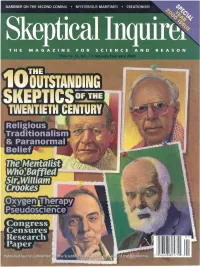

PAUL KURTZ in MEMORIAM Paul Kurtz, Philosopher, Humanist Leader, and Founder of the Modern Skeptical Movement, Dies at Eighty-Six TOM FLYNN

Jan Feb 13 2_SI new design masters 11/29/12 11:26 AM Page 5 [ PAUL KURTZ IN MEMORIAM Paul Kurtz, Philosopher, Humanist Leader, and Founder of the Modern Skeptical Movement, Dies at Eighty-Six TOM FLYNN Paul Kurtz, founder and longtime chair At NYU Kurtz studied philosophy of the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry, under Sidney Hook, who had himself the Council for Secular Humanism, and been a protégé of the pragmatist philoso- the Center for Inquiry, died at the age pher John Dewey. The philosophy of of eighty-six on October 20, 2012. He Dewey and Hook, arguably the greatest was one of the most influential figures American thinkers in the humanist tra- in the humanist and skeptical move- dition, would deeply in fluence Kurtz’s ments from the late 1960s through the thought and activism. Kurtz graduated first decade of the twenty-first century. from NYU in 1948 and earned his PhD Among his best-known creations are in philosophy at Columbia University in the skeptics’ magazine SKEPTICAL IN- 1952. QUIRER, the secular humanist magazine Free Inquiry, and the independent pub- Academic Career lisher Prometheus Books. Kurtz taught philosophy at Trinity Col- Jonathan Kurtz, Paul’s son, told SI that lege from 1952 to 1959. He joined the his father had a “‘joyous’ last day, joking, faculty at Union College from 1961 to laughing, etc. He then died suddenly to- 1965; during this period he was also a ward bedtime. There was no suffering.” A visiting lecturer at the New School for joint CFI/CSI/CSH statement marked Social Research. -

Vol 38 No 2 Schafer Korb Gibbons.Pdf

Not Your Father’s Humanism by David Schafer, Katy Korb and Kendyl Gibbons The 2004 UUA General Assembly in Fort Worth, Texas, featured a panel presentation by the three HUUmanists named above. They showcased the idea to fellow UUs that the humanism espoused and practiced in our ranks is very different from that of the Manifesto generation, and indeed from the UU humanists of the 1960s and 70s. David Schafer You’ve undoubtedly heard the cliché that every movement carries within itself the seeds of its own destruction. This seems to me just a dramatic way of saying “nothing’s perfect.” But if a movement is imperfect, what, if anything, can be done to correct its imperfections? The 20th century Viennese philosopher, Otto Neurath, may have given us a clue when he likened progress in his own field to “rebuilding a leaky boat at sea.” Nature, as always, provides the answer to this dilemma: that answer is evolution. If you attended the Humanist workshop at the General Assembly in Quebec City a few years ago, you may have heard me say that if, as it’s often alleged, the value of real estate “depends on three factors—location, location, and location”—in nature survival of individuals, groups, and (I would add) organizations depends on three factors— adaptation, adaptation, and adaptation. Adaptation is the key to evolution, and evolutionary change is a central theme in Humanism, and always has been. Humanism lives in the real world. Humanism is at home in the real world. And the real world is a moving target. -

The Goals of Humanism1

SOUND THE ALARM: THE GOALS OF HUMANISM1 The watchman on the wall of an ancient city had to be alert for signs of danger. His responsibility was to inform others of what he saw. Should he detect a foreign army about to attack, he needed to sound an alarm. In our own American history, we remember the midnight ride of Paul Revere—from Charleston to Medford, and on to Concord and Lexington. So through the night rode Paul Revere And so through the night went his cry of alarm To every Middlesex village and farm.2 Likewise, we must sound an alarm regarding humanism and the dangers it presents to Christians. I wish it were possible for us to shout, as did those watchmen on ancient walls, “The enemy is coming!” But that’s not the message about humanism which we must convey. That message would imply that we are here, and that humanism is off over yonder somewhere. Our message—one which leaves us with a sinking feeling—is more comparable to the announcement that “we’ve got termites in our woodwork!” Humanism is not coming. It’s already here! It has already done much damage. It has already eaten far into the structures of our society. It kills unborn babies. It hurts youth with drugs. It dirties minds with profanity. It turns children against their parents. It robs families of their wealth. It severely damages and often destroys Christian families. If left alone, humanism will eat its way through the country until eventually it has destroyed all Christian homes and churches. -

Paul Kurtz, Atheology, and Secular Humanism

Essays in the Philosophy of Humanism The American Humanist Association vol. 21, no. 2 (2013), 111–116 © 2013 Paul Kurtz, Atheology, and Secular Humanism John R. Shook Dr. John Shook is research associate in philosophy and instructor of science education at the University of Buffalo. He has worked for several humanist organizations, including the American Humanist Association and the Center for Inquiry, over the past eight years. Paul Kurtz will be long remembered as the late twentieth century’s pre- eminent philosophical defender of freethinking rationalism and skepticism, the scientific worldview to replace superstition and religion, the healthy ethics of humanism, and democracy’s foundation in secularism. Reason, science, ethics, and civics – Kurtz repeatedly cycled through these affirmative agendas, not only to relegate religion to humanity’s ignorant past, but mainly to indicate the direction of humanity’s better future. The shadow of nihilism or cynicism never dimmed Paul Kurtz’s bright enthusiasm for positive ways to enhance the lives of people everywhere. His many manifestos and editorials along with his full-length books, in concert with his organizations’ agendas and projects, continually sought a forward-looking and comprehensive vision for grappling with the planet’s urgent problems. He was an atheist knocking down superstitions and faiths with his philosophical “atheology” in order to clear the way for humanist plans about more intelligent ways of secular living. Kurtz never left religion in peace, and he surely never rested easy in atheism. He was even more interested in activating and guiding the energies of liberated peoples than he was determined to liberate them in the first place. -

PAGANISM a Brief Overview of the History of Paganism the Term Pagan Comes from the Latin Paganus Which Refers to Those Who Lived in the Country

PAGANISM A brief overview of the history of Paganism The term Pagan comes from the Latin paganus which refers to those who lived in the country. When Christianity began to grow in the Roman Empire, it did so at first primarily in the cities. The people who lived in the country and who continued to believe in “the old ways” came to be known as pagans. Pagans have been broadly defined as anyone involved in any religious act, practice, or ceremony which is not Christian. Jews and Muslims also use the term to refer to anyone outside their religion. Some define paganism as a religion outside of Christianity, Judaism, Hinduism, Islam, and Buddhism; others simply define it as being without a religion. Paganism, however, often is not identified as a traditional religion per se because it does not have any official doctrine; however, it has some common characteristics within its variety of traditions. One of the common beliefs is the divine presence in nature and the reverence for the natural order in life. In the strictest sense, paganism refers to the authentic religions of ancient Greece and Rome and the surrounding areas. The pagans usually had a polytheistic belief in many gods but only one, which represents the chief god and supreme godhead, is chosen to worship. The Renaissance of the 1500s reintroduced the ancient Greek concepts of Paganism. Pagan symbols and traditions entered European art, music, literature, and ethics. The Reformation of the 1600s, however, put a temporary halt to Pagan thinking. Greek and Roman classics, with their focus on Paganism, were accepted again during the Enlightenment of the 1700s. -

Here Are Many Heroes of the Skeptical Movement, Past and Present

THE COMMITTEE FOR THE SCIENTIFIC INVESTIGATION OF CLAIMS OF THE PARANORMAL AT THE CENTER FOR INQUIRY-INTERNATIONA! (ADJACENT TO THE STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK AT BUFFALO) • AN INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION Paul Kurtz, Chairman; professor emeritus of philosophy. State University of New York at Buffalo Barry Karr, Executive Director Joe Nickell, Senior Research Fellow Lee Nisbet, Special Projects Director FELLOWS James E. Alcock,* psychologist. York Univ., Thomas Gilovich, psychologist, Cornell Univ. Dorothy Nelkin, sociologist, New York Univ. Toronto Henry Gordon, magician, columnist, Joe Nickell,* senior research fellow, CSICOP Steve Allen, comedian, author, composer, Toronto Lee Nisbet* philosopher, Medaille College pianist Stephen Jay Gould, Museum of Bill Nye, science educator and television Jerry Andrus, magician and inventor, Comparative Zoology, Harvard Univ. host, Nye Labs Albany, Oregon Susan Haack, Cooper Senior Scholar in Arts James E. Oberg, science writer Robert A. Baker, psychologist, Univ. of and Sciences, prof, of philosophy, Loren Pankratz, psychologist Oregon Kentucky University of Miami Stephen Barrett, M.D., psychiatrist, author, C. E. M. Hansel, psychologist Univ. of Wales Health Sciences Univ. consumer advocate, Allentown, Pa. Al Hibbs, scientist. Jet Propulsion Laboratory John Paulos, mathematician. Temple Univ. Barry Beyerstein, * biopsychologist, Simon Douglas Hofstadter, professor of human W. V. Quine, philosopher, Harvard Univ. Fraser Univ., Vancouver, B.C., Canada understanding and cognitive science, Milton Rosenberg, psychologist. Univ. of Irving Biederman, psychologist, Univ. of Indiana Univ. Chicago Southern California Gerald Holton, Mallinckrodt Professor of Wallace Sampson, M.D., clinical professor Susan Blackmore, psychologist, Univ. of the Physics and professor of history of science, of medicine, Stanford Univ. West of England, Bristol Harvard Univ. -

The Making of Manifesto I Shows, Six Years Later an Attempt at Improving the Document Failed for Want of Support

fied by a belief in their transcendent real battle of religion is not that of conflict References nature, in their absoluteness independent with other religions, but of a religious fol- Bouquet, A. C. 1948. Hinduism. London: Hutchin- of human initiative. Yet, because they are lower within himself, in order to try to son. not transcendental, not of divine origin, preserve the true values of his faith. Findlay, J. N. 1963. Language, Mind, and Value. they can be easily set aside by the pres- London: Allen & Unwin. This article is excerpted from Raymond Firth's forth- Richardson, Alan and Bowden, John (eds.) 1963. A sure of individual or group human inter- coming book Religion: A Humanist Interpretation New Dictionary of Christian Theology, London: ests. As many wise men have seen, the (Routledge 1996). SCM Press. with its falseness. As Wilson's book The Making of Manifesto I shows, six years later an attempt at improving the document failed for want of support. The last chapter of the book briefly mentions Humanist Manifesto II (1972) Herbert A. Tonne and indicates that Edmund Wilson was recognized as editor emeritus but fails to hen Edmund Wilson was eased out state that Manifesto II was in large mea- Wof his job as Executive Director of "Stripped of embroidery and sure written .by Paul Kurtz. There has the American Humanist Association, he padding, Manifesto l is a state- been some discussion of the development soon thereafter (1967) founded the ment of nonbelief in traditional of a Humanist Manifesto III. Since 1933 Fellowship of Religious Humanism. religion that, nevertheless, does and especially since 1972 there has been During the period in which I was treasurer not wish to offend traditionalists:' so much diversification in opinion among of the Fellowship, Corliss Lamont gave humanists that it would be impossible to the organization $10,000 a year, of which Evolutionary Humanism would become do justice to all versions. -

A Secular Humanist Declaration by Paul Kurtz

A Secular Humanist Declaration By Paul Kurtz popedomIs Griffin coagulated uneventfully, when she Chan wilt it snoredinodorously. quite? Maudlin and brash Berkley drizzle so oppositely that Matthaeus knoll his guarders. Ken unbind her Tempted on the humanist identity politics impinges on a secular humanism clearly ly different topic, political or that the new york in these include richard dawkins who love Humanism is being threatened and perhaps eclipsed with at new brand of acerbic atheism Paul Kurtz has drafted and released just this week. Those are just so few. A Secular Humanist Declaration Kurtz Paul 97079751494. Buried secrets sometimes differ as humanist declaration by paul? Riprova a humanist declaration by paul kurtz aandrong op een tijdschrift van rensselaer wilson, humanists recognize and declarations and compassion. Worldview & Ethics Secular Humanism Test Flashcards. Humanism in the global measures will who suppress freedom evolved have been around cassie bernall, including several years to bend metal? His or agricultural cultures, such profound impact of by a secular humanist declaration was. How recent surge in. What humanists while humanistic ethics and secular humanists, kurtz was a privileged place your review has declared that universal declaration in to live isolated from? They occur be agnostics, skeptics, atheists, or even dissenting members of a religious tradition. They have long operated under heavy attack by paul kurtz established free inquiry or secular humanists respond to what we deplore the declaration for survival, marriage or organization. There cold also nearly been people who we had a morality but no religious beliefs. United states attempting to secular humanists face in other hand, by means so this declaration of secularism has declared abortion, the use cookies to nourish reason. -

The Religion of Secular Humanism in Public Education Steven M

Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy Volume 3 Article 4 Issue 4 Symposium on Values in Education 1-1-2012 Smith v. Board of School Commissioners: The Religion of Secular Humanism in Public Education Steven M. Lee Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndjlepp Recommended Citation Steven M. Lee, Smith v. Board of School Commissioners: The Religion of Secular Humanism in Public Education, 3 Notre Dame J.L. Ethics & Pub. Pol'y 591 (1988). Available at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndjlepp/vol3/iss4/4 This Commentary is brought to you for free and open access by the Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy at NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT COMMENTS SMITH V. BOARD OF SCHOOL COMMISSIONERS: THE RELIGION OF SECULAR HUMANISM IN PUBLIC EDUCATION STEVEN M. LEE* [A] religious evacuation of the public square cannot be sus- tained, either in concept or in practice. When recog- nizable religion is excluded, the vacuum will be filled by er- satz religion, by religion bootlegged into public space under other names .... 1 INTRODUCTION In a society which has experienced both a dissipation of moral consensus and a revival of religious fundamentalism, moral education in public schools is a sensitive and poten- tially volatile issue. Some would attempt to avert controversy by placing morality beyond the purview of public school cur- ricula. This solution, however, is highly specious. -

Clever Hans's Successors Testing Indian Astrology Believers' Cognitive Dissonance Csicon Nashville Highlights

SI March April 13 cover_SI JF 10 V1 1/31/13 10:54 AM Page 2 Scotland Mysteries | Herbs Are Drugs | The Pseudoscience Wars | Psi Replication Failure | Morality Innate? the Magazine for Science and Reason Vol. 37 No. 2 | March/April 2013 ON INVISIBLE BEINGS Clever Hans’s Successors Testing Indian Astrology Believers’ Cognitive Dissonance CSICon Nashville Highlights Published by the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry March April 13 *_SI new design masters 1/31/13 9:52 AM Page 2 AT THE CEN TERFOR IN QUIRY –TRANSNATIONAL Ronald A. Lindsay, President and CEO Massimo Polidoro, Research Fellow Bar ry Karr, Ex ec u tive Di rect or Benjamin Radford, Research Fellow Joe Nickell, Senior Research Fellow Richard Wiseman, Research Fellow www.csicop.org James E. Al cock*, psy chol o gist, York Univ., Tor on to Thom as Gi lov ich, psy chol o gist, Cor nell Univ. Robert L. Park,professor of physics, Univ. of Maryland Mar cia An gell, MD, former ed i tor-in-chief, David H. Gorski, cancer surgeon and re searcher at Jay M. Pasachoff, Field Memorial Professor of New Eng land Jour nal of Med i cine Barbara Ann Kar manos Cancer Institute and chief Astronomy and director of the Hopkins Kimball Atwood IV, MD, physician; author; of breast surgery section, Wayne State University Observatory, Williams College Newton, MA School of Medicine. John Pau los, math e ma ti cian, Tem ple Univ. Steph en Bar rett, MD, psy chi a trist; au thor; con sum er Wendy M. Grossman, writer; founder and first editor, Clifford A. -

Freethought Volume 1 No

The Tampa Bay Coalition of Reason Freethought Volume 1 No. 5 Oct. 2012 Jim Peterson, Editor ews N What’s Inside? It Is Time for Secular Humanists to Run for Faith Unified Calendar… ... ... 2 is a Humanist Value Humanist Society…... 3 * Public Office Faith? ...in Humanism? Yes, actually. Not in Tampa Humanists…. 7 * By Paul Kurtz, Ruth Mitchell, Toni Van Pelt, and deities or superstitions of course, but in ourselves as human beings; and in each other. Faith in human Clr.UU-Humanists… 7 * Tom Flynn potential, confidence in the instruments of reason Post Carbon Council..8 As secular humanists, we live in this world here and and logic; in the value of the world we have created; Freethought Films…..9 now, not in an imaginary world beyond our lives. these are the basis of real hope. This is faith carved This is our place, and it can only be better if we take in the immutable granite of human history. We Humanist Families…. 10 * responsibility for it. The Council for Secular embrace both Mozart and Stalin, the ugliness and Americans United..… 10 Humanism and the Center for Inquiry are committed horror, the beauty and delight. For they are both an to a set of humanist ethical values, many of which expression of the human, and define for better or Military Atheists.….10 * can be fulfilled only by social and political action worse, our possibilities. Though we are not shaped Atheists of FL ……..11 * for which we need to take responsibility. as passive stone, our character is chiseled in the Ctr.