Germany 1914-1933

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nacjonalizm Wobec Problemu Europy

Nacjonalizm wobec problemu Europy ADAM WIELOMSKI Nacjonalizm wobec problemu Europy WARSZAWA 2018 © Copyright by Michał Marusik Recenzent: prof. UŁ. dr hab. Tomasz Tulejski Wydanie pierwsze Warszawa 2018 ISBN 978-83-949371-3-3 Książka ukazuje się w serii Biblioteka konserwatyzm.pl Wydawca: Klub Zachowawczo-Monarchistyczny Książkę można zamówić bezpłatnie pod adresem: sklep.konserwatyzm.pl Zamawiający pokrywa tylko koszt przesyłki. Printed in Poland Spis treści Michał Marusik, Wprowadzenie ................................................................................. 7 Kilka refleksji wstępnych od autora .......................................................................... 11 Rozdział I. Historia i definicje nacjonalizmu Trzy fale europejskiego nacjonalizmu .............................................................................17 Rozdział II. Nacjonalizm a chrześcijaństwo Nacjonalizm a katolicyzm. Pozycje i pojęcia od Piusa VI po Jana Pawła II ....................61 Religia a nacjonalistyczna myśl polityczna we Francji i w Hiszpanii. Nowe perspektywy badawcze ...................................................................................................99 ROZDZIAł III. IDEA NARODU I PAńSTWA NARODOWEGO WE FRANCJI Etat-Nation. O specyfice francuskiego rozumienia narodu ..........................................111 Pokojowa współpraca w Europie w programie francuskiego Front National ................165 Francuski Front National a kwestia religijna ................................................................177 Bibliografia -

Germany's Euro Crisis: Preferences, Management

Review of European and Russian Affairs 7 (2), 2012 ISSN 1718-4835 GERMANY’S EURO CRISIS: PREFERENCES, MANAGEMENT, AND CONTINGENCIES Michael Olender Carleton University Abstract This article applies Moravscik’s ideational liberalism to outline domestic and international influences on German state preference formation since the introduction of the euro and discusses the trends that distinguish German policy making and why they matter in the development of sustainable solutions to the ongoing euro crisis. The German government’s ideational commitments to the European project and ordoliberal principles are found to be significant determinants in preference formation, but while its commitment to Europe has remained stable over time, its commitment to ordoliberalism has wavered. The government prefers to advance European integration in line with ordoliberal principles, though in times of crisis it hardens its ordoliberal stance. This article argues that Germany will go to great lengths to keep the Eurozone intact because it is part of a grand political project, but the government’s prescription for fiscal austerity, which is underpinned by ordoliberal principles, sometimes exacerbates the euro crisis. Policy recommendations that favour flexibility are offered for Germany and other Eurozone countries. © 2012 The Author(s) www.carleton.ca/rera 2 Review of European and Russian Affairs 7 (2), 2012 Introduction How much do economic and political ideas matter in Germany, the Eurozone’s leading economy which is responsible for managing the ongoing euro crisis, and why has the crisis evolved the way that it has? This article investigates which ideational commitments inform the German government’s preference formation on Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) and whether its preferences have changed over time. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Abraham, J. H., Origins and Growth of Sociology, London: Penguin, 1973. Akenson, Donald, Small Differences: Irish Catholics and Irish Protestants 1815–1922, Dublin: Gill and Macmillan, 1991. Alder, Ken, The Measure of All Things, London: Abacus, 2004. Alexander, Jeffrey, Durkheimian Sociology: Cultural Studies, Cambridge: CUP, 1988. Alexander, Jeffrey (ed.), Real Civil Societies, London: Sage, 1998. Alpert, H., Durkheim and His Sociology, New York: Free Press, 1961. Alter, Peter, Nationalism, London: Edward Arnold, 1989. Anderson, Benedict, Imagined Communities, London: Verso, 1991. Anderson, M. S., War and Society in Europe of the Old Regime, 1618–1789, London: Fontana, 1986. Anderson, Malcolm and Bort, Eberhard (eds), The Irish Border: History, Politics and Culture, Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 1999. Anderson, Perry, ‘Components of the National Culture’, in Cockburn, Alexander and Blackburn, Robin (eds), Student Power, Penguin: London, 1969. Anderson, Perry, English Questions, London: Verso, 1992. Anderson, Perry, Origins of Postmodernity, London: Verso, 1998. Aron, Raymond, German Sociology, New York: Free Press, 1964. Aron, Raymond, Main Currents in Sociological Thought 2, London: Penguin, 1967. Augusteijn, Joost, The Irish Revolution, 1913–1923, London: Palgrave, 2002. Balfour, M., The Kaiser and His Times, London: Pelican, 1975. Beckett, J. C., The Making of Modern Ireland, 1603–1923, London: Faber, 1969. Belfast Agreement, Belfast: HMSO, 1998. Bellah, Robert, Emile Durkheim on Morality and Society, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1973. Berdahl, R. M., ‘New Thoughts on German Nationalism’, American Historical Review, vol. 77, pp. 65–80, 1972. Berger, Peter and Luckman, Thomas, The Social Construction of Reality, London: Penguin, 1966. Berlin, Isaiah, The Crooked Timber of Humanity, London: Fontana, 1991. -

Conservative Revolution”

Introduction Countercultures Ideologies and Practices Alternative Visions BEYOND HISTORICISM: UTOPIAN THOUGHT IN THE “CONSERVATIVE REVOLUTION” Robbert-Jan Adriaansen The “Conservative Revolution” presents a paradox to contemporary scholars, as the idea of a revolution seems to challenge the very foundations of conservatism. “Conservative Revolution” is a col- ligatory concept; it does not refer to any particular historical event but to a current in intellectual thought that gained prominence in the German Weimar Republic.1 Comprising a broad array of right- wing authors, thinkers, and movements, the concept of “Conserva- tive Revolution” was introduced as an analytical category by Armin Mohler in his dissertation Die Konservative Revolution in Deutschland (1949).He defi ned it as “that spiritual movement of regeneration that tried to clear away the ruins of the nineteenth century and tried to 1 Colligatory concepts are create a new order of life.”2 Covering vö lkisch authors, Young Con- concepts used by histori- ans to create unity in the servatives such as Oswald Spengler and Arthur Moeller van den morass of past ideas and Bruck, National Revolutionaries — like brothers Ernst and Friedrich events; they bring them together under a general Georg Jü nger — and also two more organized movements, the metaphor such as Landvolkbewegung and the Bü ndische Jugend, Mohler presented a “Renaissance,” “Industrial Revolution,” or, indeed, taxonomy of a heterogeneous array of thinkers and organizations that “Conservative Revolution.” did not regard itself as a unifi ed movement but shared a common See William H. Walsh, “Colligatory Concepts in attitude to life, society, and politics. History,” in The Philosophy of History, ed. -

Explaining EMU Reform

JCMS 2005 Volume 43. Number 5. pp. 947–68 Explaining EMU Reform SHAWN DONNELLY University of Bremen Abstract This article develops a model to explain the roles of national governments in the reform process of rules for economic and monetary union (EMU) in Europe. A study of Germany, France and Spain underlines the importance of electoral politics and institutional arrangements in producing distinctive policy triangles on domestic economic and budget policy, and subsequent demands for specific EMU rules. It employs budget policy analysis to illustrate the collapse of stabilization state politics in France and Germany, leading to the reform of the Stability Pact in March 2005. Introduction Economic and monetary union (EMU) remains a controversial policy issue in Europe, not least because of the monetarist orthodoxy entrenched in its system of rules and institutions. The story of its achievement is often sold as one of an agreement based on common acceptance of neoliberal economic principles (Verdun, 2000), which means here the acceptance of central bank independence and balanced government budgets. Convinced of the futility of Keynesian demand management and the success of German monetarism and fiscal conservatism, European governments agreed on a common currency and institutionalized central bank independence based on the German policy paradigm. The subsequent entrenchment of these principles in European institutions endows them with longevity and power over national economic policy (Dyson, 2000). Since 2002, the difficulties of the French, German, © 2005 The Author(s) Journal compilation © 2005 Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2005 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK and 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148, USA 948 SHAWN DONNELLY Portuguese, Greek, Dutch and Italian governments in adhering to the terms of the Stability Pact1 (Commission, 2004) and, in March 2005, the Council’s decision to alter the Pact have raised the need for reassessment. -

Inequality, Education and the Social Sciences: the Historical Reproduction of Inequalities Through Secondary Education in India and Germany

Inequality, Education and the Social Sciences: The Historical Reproduction of Inequalities through Secondary Education in India and Germany Dissertation Zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades doctor philosophiae (Dr. phil.) der Kultur-, Sozial- und Bildungswissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin von Michael Robert Kinville Präsidentin der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Prof. Dr.–Ing. Dr. Sabine Kunst Dekanin der Kultur-, Sozial- und Bildungswissenschaftlichen Fakultät Prof. Dr. Julia von Blumenthal Gutachter: 1. Prof. Dr. Boike Rehbein 2. Prof. Dr. Gregor Bongaerts Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 24. Oktober 2016 Zusammenfassung Die konzeptionelle Verbindung zwischen Bildung und Gesellschaft, die im 19. Jahrhundert deutlich gemacht und wissenschaftlich begründet wurde, wird oft als selbstverständlich betrachtet. Diese veraltete Verbindung bildete aber die Basis für Bildungsreformen im Sekundärbereich in Deutschland und Indien in der zweiten Hälfte des 20. Jahrhunderts. Diese Arbeit unternimmt den Versuch, zum Verständnis dieser Verzögerung zwischen den Ideen und den Reformen, die sie einrahmten, beizutragen, indem sie eine geeignete Theorie der Verbindung zwischen Bildung und einer komplexen Gesellschaft aufstellt. Grundsätzliche Annäherungen an Gesellschaft und Bildung treten in Dialog mit post-kolonialen und kritischen Theorien. Universalistische Annahmen werden problematisiert, und eine offene Lösung für die Vorstellung zukünftiger Reformen wird präsentiert. Nationale Bildungsreformen in Indien und Deutschland nach ihren „Critical Junctures“ von 1947/1945 werden eingehend und chronologisch verglichen, um einen spezifischen Charakter historisch- und bildungs-bedingter Reproduktion beider Länder herauszuarbeiten sowie einen gemeinsamen Lernprozess zu ermöglichen. Abschließend wird eine Lösung des Problems in der Form offener Bildung präsentiert. Bildung als öffentliches Gut muss nicht zwangsläufig nur auf soziale Probleme reagieren, stattdessen kann sie verändert werden, um sozialen Wandel voran zu treiben. -

Europe Since 1945

SAMPLE SYLLABUS – SUBJECT TO CHANGE HIST-UA9156L01 Europe Since 1945 NYU London Instructor Information ● Andrew Crozier ● Mondays 10.30 to 11.30. Location 105 Course Information ● Mondays and Wednesdays 9.00-10.15am ● Location 105 ● None Course Overview and Goals The course will begin with an examination of the background to and condition of Europe in 1945. The outbreak of the Cold War and the division of Europe will be discussed as will the promotion of European unity, the establishment of NATO and the emergence of COMECON and the Warsaw Pact. The pressures leading to the creation of the European Economic Community (EEC) will be considered together with the firm establishment of the democratic principle in Western Europe. The Suez Crisis and Decolonisation in Britain and France will be explored together with the corollary, the first application by Britain for membership of the EEC. The effect of President de Gaulle’s presidency on France, NATO and the EEC will be considered. The end of Stalinism in the USSR will be examined as will the first cracks in the Soviet Empire in Eastern Europe in Hungary and Poland. This will be followed by a discussion of the merits and demerits of Khrushchev’s period in power, the U2 crisis and the construction of the Berlin Wall. The Prague Spring off 1968 will be discussed. The continued integration of Europe will be analyzed together with the impact of Ostpolitik in Germany. Brezhnev’s domination of the USSR and Détente in the 1970s will be examined. Following this, the forces that led to the triumph of Neo-Liberalism in Britain will be considered, as will the return of conservatism in Germany and the cohabitation of Mitterrand’s France. -

1 What Is Conservatism? History, Ideology and Party* Richard Bourke (Queen Mary University of London)

What is Conservatism? History, Ideology and Party* Richard Bourke (Queen Mary University of London) [email protected] Abstract Is there a political philosophy of conservatism? A history of the phenomenon written along sceptical lines casts doubt on the existence of a transhistorical doctrine, or even an enduring conservative outlook. The main typologies of conservatism uniformly trace its origins to opposition to the French Revolution. Accordingly, Edmund Burke is standardly singled out as the ‘father’ of this style of politics. Yet Burke was de facto an opposition Whig who devoted his career to assorted programmes of reform. In restoring Burke to his original milieu, the argument presented here takes issue with twentieth-century accounts of conservative ideology developed by such figures as Karl Mannheim, Klaus Epstein and Samuel Huntington. It argues that the idea of a conservative tradition is best seen as a belated construction, and that the notion of a univocal philosophy of conservatism is basically misconceived. Keywords: Conservatism, Edmund Burke, Karl Mannheim, French Revolution, enlightenment, party, ideology, scepticism. I: Scepticism and Political Theory In the rousing final paragraph of his ‘Introduction’ to Jealousy of Trade, Istvan Hont wrote that ‘History is the tool of skeptics’ (Hont, 2005: p. 156). The phrase has often been quoted, but what does it mean? Hont’s purpose in the passage was to set out an agenda for the history of political thought. He was arguing that it made no sense to revive forgotten ideological alternatives that might ‘miraculously’ answer current problems in political theory. The past, he seemed to be saying, has no such purchase on the present. -

What Is Conservatism? History, Ideology and Party

Article EJPT European Journal of Political Theory 2018, Vol. 17(4) 449–475 ! The Author(s) 2018 What is conservatism? Article reuse guidelines: History, ideology and party sagepub.com/journals-permissions DOI: 10.1177/1474885118782384 journals.sagepub.com/home/ept Richard Bourke Queen Mary University of London, UK Abstract Is there a political philosophy of conservatism? A history of the phenomenon written along sceptical lines casts doubt on the existence of a transhistorical doctrine, or even an enduring conservative outlook. The main typologies of conservatism uniformly trace its origins to opposition to the French Revolution. Accordingly, Edmund Burke is standardly singled out as the ‘father’ of this style of politics. Yet Burke was de facto an opposition Whig who devoted his career to assorted programmes of reform. In restoring Burke to his original milieu, the argument presented here takes issue with 20th-century accounts of conservative ideology developed by such figures as Karl Mannheim, Klaus Epstein and Samuel Huntington. It argues that the idea of a conservative tradition is best seen as a belated construction, and that the notion of a univocal philosophy of conservatism is basically misconceived. Keywords Conservatism, Edmund Burke, enlightenment, French Revolution, ideology, Karl Mannheim, party, scepticism Scepticism and political theory In the rousing final paragraph of his ‘Introduction’ to Jealousy of Trade, Istvan Hont wrote that ‘History is the tool of skeptics’ (Hont, 2005: 156). The phrase has often been quoted, but what does it mean? Hont’s purpose in the passage was to set out an agenda for the history of political thought. He was arguing that it made no sense to revive forgotten ideological alternatives that might ‘miraculously’ answer current problems in political theory. -

German 132 Fall 2014-15 Dynasties, Dictators, Democrats: History And

German 132 Fall 2014-15 Dynasties, Dictators, Democrats: History and Politics in Germany Instructor: Russell A. Berman Office 260-201, x30169 Berman @stanford.edu This course explores the trajectory of German history during the past two centuries: from the monarchist and imperial regimes, the experiences of dictatorships in the Nazi era and Communist East Germany, and the gradual growth of democratic political culture, from the Weimar Republic to today’s unified Germany. The course provides an overview of historical change, with particular emphasis on political history, including the history and transformation of the state, conflicts of political ideologies, the role of national identity and nationalism, and the interaction between German national formation and international processes. Students will come to understand the origins of the political institutions of contemporary Germany and how they emerged from historical experience. The center of the course is the examination of primary sources—historical documents— and scholarly analyses. In addition to exposing students to the trajectory of German history, the course also highlights how historical accounts, i.e., the narrative of history, depends on the interpretation of primary evidence. The historical documents and some of the secondary sources will be in German, and the course will be conducted largely in German. It is open to students who have completed German 21 or a course at the 120 level. Students who have questions about the level of German language skills required are invited -

Designing One Nation

Designing One Nation The Politics of Economic Culture and Trade in Divided Germany Katrin Schreiter Oxford University Press Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries. Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press Madison Avenue, New York, NY , United States of America. © Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above. You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Schreiter, Katrin, author. Title: Designing one nation: the politics of economic culture and trade in divided Germany / Katrin Schreiter. Description: New York: Oxford University Press, . | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Identiers: LCCN (print) | LCCN (ebook) | ISBN HARDCOVER | ISBN PDF Subjects: LCSH: Germany (West)—Relations—Germany (East) | Germany (East)-- Relations--Germany (West) | Germany--History-- - . | German reunication question ( - ) | Germany--Economic conditions-- -| Industrial design--Social aspects--Germany. | Functionalism in art--History. Classication: LCC DD . -

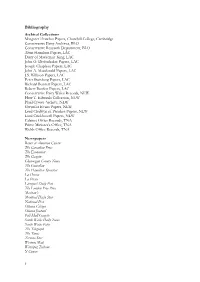

Bibliography

Bibliography Archival Collections Margaret Thatcher Papers, Churchill College, Cambridge Conservative Party Archives, BLO Conservative Research Department, BLO Alvin Hamilton Papers, LAC Diary of Mackenzie King, LAC John G. Diefenbaker Papers, LAC Joseph Chapleau Papers, LAC John A. Macdonald Papers, LAC J.S. Willison Papers, LAC Peter Stursberg Papers, LAC Richard Bennett Papers, LAC Robert Borden Papers, LAC Conservative Party Wales Records, NLW Huw T. Edwards Collection, NLW Plaid Cymru Archive, NLW Gwynfor Evans Papers, NLW Lord Cledwyn of Penrhos Papers, NLW Lord Crickhowell Papers, NLW Cabinet Office Records, TNA Prime Minister‟s Office, TNA Welsh Office Records, TNA Newspapers Baner ac Amserau Cymru The Canadian Press The Economist The Gazette Glamorgan County Times The Guardian The Hamilton Spectator La Devoir La Presse Liverpool Daily Post The London Free Press Maclean’s Montreal Daily Star National Post Ottawa Citizen Ottawa Journal Pall Mall Gazette South Wales Daily News South Wales Echo The Telegraph The Times Toronto Star Western Mail Winnipeg Tribune Y Cymro 1 Interviews Dr. Hywel Williams (11/07/11) Rt. Hon. Lord Crickhowell (29/06/11) Rt. Hon. Lord Hunt of Wirral (29/06/11) Rt. Hon. Lord Roberts of Conwy (8/04/11) Alun Cairns MP (29/03/11) Guto Bebb MP (29/03/11) David Davies MP 29/03/11) Glyn Davies MP (29/03/11) Professor Tom Flanagan (01/11/10) Primary and Secondary Sources Adams, J., Clark, M., Ezrow, L. and Glasgow, G. „Understanding Change and Stability in Party Ideologies: Do Parties Respond to Public Opinion or to Past Election Results?,‟ British Journal of Political Science, 34 (2004), pp.