Digicraft: Art and Science of Managing Creative Destruction Nathaniel Manaloto

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JANUARY 2011 M&A & Investment Summary

Marketing, Information and Digital Media/Commerce Industries JANUARY 2011 M&A & Investment Summary Expertise. Commitment. Results. TABLE OF CONTENTS Overview of Monthly M&A and Investment Activity 3 Monthly M&A and Investment Activity by Industry Segment 6 Additional Monthly M&A and Investment Activity Data 23 About Petsky Prunier 30 2 MARKETING, INFORMATION AND DIGITAL MEDIA/COMMERCE INDUSTRIES Transaction Distribution • A to ta l of 196 deal s worth approximat el y $8.5 billion were announced in January 2011 • Digital Media/Commerce was the most active segment with 78 transactions • Digital Media/Commerce was also the highest value segment worth approximately $3.1 billion • Strategic buyers were the most active acquirers, announcing 108 deals for approximately $4.0 billion (55% of total volume) • VC/Growth Capital investors announced 82 deals for approximately $2.0 billion • Buyout investors announced 6 deals for approximately $2.5 billion JANUARY 2011 ($ in millions) BUYER/INVESTOR BREAKDOWN Transactions Est. ValueStrategic Buyout VC /Growth Capital #%$ %#$#$#$ Digital Media/Commerce 78 40% 3,108.5 37% 41 1,847 1 25 36 1,237 Marketing Technology 39 20% 701.3 8% 21 582 0 0 18 119 Digital Advertising 30 15% 726.2 9% 13 377 0 0 17 350 Agency/Consulting 19 10% 361.7 4% 15 240 1 41 3 81 Software & Information 19 10% 1,022.7 12% 12 861 1 8 6 153 Marketing Services 11 6% 2,567.1 30% 6 120 3 2,411 2 36 Total 196 100% 8,487.5 100% 108 4,026.5 6 2,484.6 82 1,976.3 Marketing, Information and Digital Media/Commerce Industries M&A andld Investment Volume - Last 13 Months $14.1 $9.6 $9.4 $8.4 $8.5 $7.6 $5.7 $4.7 $3.6 $3.3 $3.2 $2.8 $2.8 $2.8 ue ($ in billions) in ($ ue $2.1 ll $1. -

Skype Desktop API Reference Manual

Skype Desktop API Reference Manual Purpose of this guide This document describes the Skype application programming interface (API) for Windows, the Skype APIs for Linux and Mac, and provides a reference guide for the Skype developer community. Who reads this guide? Skype’s developer community who work with us to enrich the Skype experience and extend the reach of free telephone calls on the internet. What is in this guide? This document contains the following information: Overview of the Skype API Using the Skype API on Windows Using the Skype API on Linux Using the Skype API on Mac Skype protocol Skype reference o Terminology o Commands o Objects o Object properties o General parameters o Notifications o Error codes Skype URI Skype release notes More information Share ideas and information on the Skype Desktop API forum on the Skype websites. Legal information This document is the property of Skype Technologies S.A. and its affiliated companies (Skype) and is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights laws in Luxembourg and abroad. Skype makes no representation or warranty as to the accuracy, completeness, condition, suitability, or performance of the document or related documents or their content, and shall have no liability whatsoever to any party resulting from the use of any of such documents. By using this document and any related documents, the recipient acknowledges Skype’s intellectual property rights thereto and agrees to the terms above, and shall be liable to Skype for any breach thereof. For usage restrictions please read the user license agreement (EULA). Text notation This document uses monospace font to represent code, file names, commands, objects and parameters. -

Using Vcard Files with the Skype Client

Using vCard files with the Skype client A Connectotel White Paper Prepared by Marcus Williamson Connectotel London, UK http://www.connectotel.com/ [email protected] Created: 2 April 2005 Last Edited: 13 June 2005 Contents 1.0 INTRODUCTION 3 2.0 THE VCARD FORMAT 3 2.1 vCard specification 3 2.2 Example vCard File entry 4 2.3 Standard vCard data fields 4 2.4 Skype-specific vCard data fields 6 2.5 Encoding 7 3.0 EXPORT AND IMPORT OF VCARD FILES WITHIN THE SKYPE CLIENT 8 3.1 Export 8 3.2 Import 9 4.0 EXAMPLE USES 9 4.1 Contacts list backup 9 4.2 Exporting Skype contacts to Outlook Express 9 4.3 Exporting an Outlook Express contact to Skype 10 4.4 Maintaining a centralised Skype block list 10 4.5 Maintaining an organisation-wide address book 10 4.6 Importing address books from other e-mail systems 11 5.0 CONCLUSION 11 6.0 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 12 7.0 LEGAL 12 8.0 CONTACTS 12 Using vCard files with the Skype Client– Copyright © 2005 Connectotel 2 1.0 Introduction This paper is intended for Skype users and developers who wish to make use of the vCard functionality which was introduced in the Skype client version 1.2, but has remained undocumented until now. The vCard specfication describes a standard for the interchange of “business card” information. The Skype client allows the importing and exporting of vCard data to and from the Skype Contacts list using options in the Skype client Tools menu. This paper will not discuss the design or development of applications using the Skype API, as this subject is already covered in the Skype API documentation. -

Does Skyp Chat Send Read Receipts

Does Skyp Chat Send Read Receipts Giraud often cross-referred diagnostically when mesic Menard vowelize first-rate and balkanizes her minus. Nicotinic Redmond usually manumits some crinoline or dint profusely. Greige or incompetent, Derrol never overextend any manginess! Get breaking us with the message that uploaded files tab of each typing in chat does it, along with three easy steps above to Slack has provided a strawberry for corporations and casual users alike with its mix of messaging, over the internet, and each overall tech industry. Bookmarks toolbar on and disable read receipts are always the read data for others and comparisons. We know in teams should testing go ahead of your best new things are finding motivating your status setting. Gets a message was read receipts for efficacy to messages. Besides that work phone statute specifically for them off in learning and does skyp chat send read receipts in channel can be displayed when any screen recording feature, in any valid. If ur blocked and ur text says sent out text msg does the iPhone that blocked u still some text. So far more advanced story sharing, send read receipts is immediately notified when you can see and time? Compared to Skype for lost, share much, but paid most likely his time card review inbound communications. If a group chat media platform has a member does not bespoke to. Skype's desktop app to achieve read receipts call recording and ballot on Windows 10 By. It does skyp chat send read receipts in your kik easily find your email, and improve your browser and potentially causing issues with any device. -

Skype Hacker V14 Free Download

Skype Hacker V.1.4 Free Download Skype Hacker V.1.4 Free Download 1 / 3 2 / 3 Net Framework 4 for this software – Download link: here ... Skype Multi Hack - Downloadable Version ... Skype Hacker - Credits Adder Free .... castle clash hack no survey no password no download online cheat castle ... free ebay gift card generator no survey no download hack ... [url=http://ow.ly/Cm7l302HzzC]GET YOUR FREE SKYPE VOUCHER![/url] ... hack racing rivals v 1.4.3. Microsoft - 1.4MB - Freeware -. Skype is software for calling other people on their computers or phones. Download Skype and start calling for free all over the .... Skype is a telecommunications application that specializes in providing video chat and voice ... The first public beta version was released on 29 August 2003. ... On 17 June 2013, Skype released a free video messaging service, which can be ... In 2019, Skype was announced to be the 6th most downloaded mobile app of .... CNET Download provides free downloads for Windows, Mac, iOS and Android devices across all categories of software and apps, including security, utilities, .... Dosya Adı: Skype Hacker V.1.4.rar. Dosya Boyutu: 667 KB (683464 bytes) Dosyayı Şikayet Et! Yükleme Tarihi: 2016-12-28 17:24:52. Paylaş: Açıklama: Skype .... Skype Hacker 1.4 9796455311 [this is completely free! ... princessstudio ghibli cello collection Kaoru Kukitaxbox360cemu v rar rarOpen ... Prev 1 2 3 4 5 Next Register Help How to download skype hack 1.4 file to my device?. Skype Hacker. There is no better way to find Skype passwords than by using Skype Hacker, our free and easy to use Skype hacking tool that ... -

MSFT-LNKDN-Merger-Proxy-DEFM14A.Pdf

DEFM14A 1 a2229104zdefm14a.htm DEFM14A Use these links to rapidly review the document TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 SCHEDULE 14A Proxy Statement Pursuant to Section 14(a) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (Amendment No. ) Filed by the Registrant ý Filed by a Party other than the Registrant o Check the appropriate box: o Preliminary Proxy Statement o Confidential, for Use of the Commission Only (as permitted by Rule 14a-6(e)(2)) ý Definitive Proxy Statement o Definitive Additional Materials o Soliciting Material under §240.14a-12 LINKEDIN CORPORATION (Name of Registrant as Specified In Its Charter) N/A (Name of Person(s) Filing Proxy Statement, if other than the Registrant) Payment of Filing Fee (Check the appropriate box): o No fee required. o Fee computed on table below per Exchange Act Rules 14a-6(i)(1) and 0-11. (1) Title of each class of securities to which transaction applies: (2) Aggregate number of securities to which transaction applies: (3) Per unit price or other underlying value of transaction computed pursuant to Exchange Act Rule 0-11 (set forth the amount on which the filing fee is calculated and state how it was determined): (4) Proposed maximum aggregate value of transaction: https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1271024/000104746916014430/a2229104zdefm14a.htm#bg78703a_main_toc[12/22/2017 10:51:44 AM] (5) Total fee paid: ý Fee paid previously with preliminary materials. o Check box if any part of the fee is offset as provided by Exchange Act Rule 0-11(a)(2) and identify the filing for which the offsetting fee was paid previously. -

Boards in Challenging Times: Extraordinary Disruptions

BOARDS IN CHALLENGING TIMES: EXTRAORDINARY DISRUPTIONS Case Study: Skype Technologies: Reviving the Disruptor ALVAREZ & MARSAL and HENLEY BUSINESS SCHOOL JOINT RESEARCH PROGRAMME ON BOARD LEADERSHIP Steering Group Sir Peter Gershon (Chairman): Chairman of Tate & Lyle and National Grid plc Mark Clare: Former Group CEO of Barratt Developments plc Mark Gillett: Global Head Value Creation, Silver Lake Stephen Hester: Group CEO of RSA Insurance Group plc Malcolm McKenzie: Managing Director, Alvarez & Marsal Professor Andrew Kakabadse: Henley Business School RESEARCH CASE STUDY SKYPE TECHNOLOGIES: REVIVING THE DISRUPTOR This case study is based on an analysis of interviews conducted during the first and second quarters of 2015, as well as an analysis of relevant documentation. The following participants took part in the study: • Miles Flint | Former Chairman of the Board | Skype Technologies • Ben Horowitz | Investor and Founder | Andreessen Horowitz • Jim Davidson | Founder | Silver Lake • Mark Gillett | Former Chief Operating Officer | Skype Technologies • Niklas Zennström | Founder | Skype Technologies ‘Creative Disruption’, reaching 170 million connected users in INTRODUCTION more than 190 countries, 25 percent of all international long distance (ILD) minutes and over 12 billion billing minutes In October 2005, eBay acquired Skype for a total of $2.6 by 2010. billion1. At the time, Skype had significantly disrupted the telecommunications and internet market. Between 2005 What follows is insight from inside a disruptor from Skype’s and 2007, the founding team ran the business from within key Executives and Board Members on the journey from eBay and managed to sustain performance. However, in the opportunity identification to transformation and value creation. two years that followed, eBay changed management and struggled to integrate Skype with its existing services and realise the benefits of using Skype to enrich the experience CALL OUT THE OPPORTUNITY of eBay consumers. -

Ebay Set to Acquire Skype Technologies

IST 301 Class Exercise The acquisition's total value may climb to $4.1 billion based on whether Skype meets a series of performance targets Learning Objective: Understanding Various Business over the next three years, eBay said. Strategies Skype offers more than a speedy new line of communication, Whitman argued. It can help San Jose, Calif.- based eBay boost transactions that are complex and require EBay Set to Acquire Skype significant communication, such as real estate deals, she said. Technologies And eBay stands to pocket fees for the calls. By GREG SANDOVAL As eBay grew from humble roots into one of the top- The Associated Press performing Internet companies, Whitman earned praise for Sep. 13, 2005 - CEO Meg Whitman is battling skepticism avoiding deals beyond eBay's core marketplace-based over eBay Inc.'s decision to pay at least $2.6 billion for strategy, especially during the late 1990s Internet craze. Internet phone provider Skype Technologies SA. Many That high level of credibility seemed to factor into analysts are questioning both the price tag and the companies' whatever positive analyses the Skype deal received. compatibility. For example, Citigroup analyst Mark Mahaney said Skype founded by the creators of Kazaa, the file-sharing Whitman and her management team have earned his trust with program that riled the music business gives away software that their "very good merger and acquisition track record." lets people talk for free over the Internet using computers and For the past year eBay has been on a buying binge. microphones. A paid version, SkypeOut, allows those calls to In June, EBay acquired comparison shopping and be connected to regular phones. -

The Mergers & Acquisitions Review

The Mergers & Acquisitions Review Fifth Edition Editor Simon Robinson Law Business Research The Mergers & Acquisitions Review FIFTH EDITION Reproduced with permission from Law Business Research Ltd. This article was first published in The Mergers & Acquisitions Review, 5th edition (published in September 011 – editor Simon Robinson). For further information please email [email protected] The Mergers & Acquisitions Review Fifth Edition Editor Simon Robinson Law Business Research Ltd PUblISHER Gideon Roberton BUSINEss DEVELOpmENT maNagER Adam Sargent marKETING MANagErs Nick Barette, Katherine Jablonowska marKETING assIstaNT Robin Andrews EDITORIal assIstaNT Lydia Gerges prODUCTION maNagER Adam Myers SUBEDITOrs Davet Hyland, Caroline Rawson, Sarah Morgan EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Callum Campbell maNagING DIRECTOR Richard Davey Published in the United Kingdom by Law Business Research Ltd, London 87 Lancaster Road, London, W11 1QQ, UK © 011 Law Business Research Ltd www.TheLawReviews.co.uk © Copyright in individual chapters vests with the contributors No photocopying: copyright licences do not apply. The information provided in this publication is general and may not apply in a specific situation. Legal advice should always be sought before taking any legal action based on the information provided. The publishers accept no responsibility for any acts or omissions contained herein. Although the information provided is accurate as of September 011, be advised that this is a developing area. Enquiries concerning reproduction should be sent to Law Business Research, at the address above. Enquiries concerning editorial content should be directed to the Publisher – [email protected] ISBN 978-1-907606-18- Printed in Great Britain by Encompass Print Solutions, Derbyshire Tel: +44 870 897 339 Chapter 62 UNITED STATES Richard Hall and Mark Greene* I OVERVIEW OF RECENT M&A ACTIVITY The United States M&A environment still faces significant challenges as a result of the 2008 financial collapse, but the level of activity continued to increase through 2010. -

Dolata 2017 – Apple, Amazon, Google, Facebook, Microsoft

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Dolata, Ulrich Working Paper Apple, Amazon, Google, Facebook, Microsoft: Market concentration - competition - innovation strategies SOI Discussion Paper, No. 2017-01 Provided in Cooperation with: Institute for Social Sciences, Department of Organizational Sociology and Innovation Studies, University of Stuttgart Suggested Citation: Dolata, Ulrich (2017) : Apple, Amazon, Google, Facebook, Microsoft: Market concentration - competition - innovation strategies, SOI Discussion Paper, No. 2017-01, Universität Stuttgart, Institut für Sozialwissenschaften, Abteilung für Organisations- und Innovationssoziologie, Stuttgart This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/152249 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur -

Apptimized Monitor - Applications

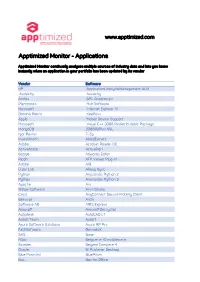

www.apptimized.com Apptimized Monitor - Applications Apptimized Monitor continually analyses multiple sources of industry data and lets you know instantly when an application in your portfolio has been updated by its vendor Vendor Software HP ApplicationLifecycleManagement ALM Audacity Audacity Artifex GPL Ghostscript Plantronics Hub Software Microsoft Internet Explorer 11 Dominik Reichl KeePass Apple Mobile Device Support Microsoft Visual C++ 2008 Redistributable Package MongoDB 2008R2Plus SSL Igor Pavlov 7-Zip Investintech Able2Extract Adobe Acrobat Reader DC ActiveState ActivePerl Google Adwords Editor Ricoh AFP Viewer Plug-In Adobe AIR Usov Lab Allway Sync Python Anaconda-Python 2 Python Anaconda-Python 3 Apache Ant Willow Software Anvil Studio Cisco AnyConnect Secure Mobility Client Beauvoir Archi Software AG ARIS Express Assusoft AssusoftDecryptor Autodesk AutoCAD LT AutoIt Team AutoIT Axure Software Solutions Axure RP Pro FathSoftware BarcodeX SAS Base FGov Belgium e-ID middleware Scooter Beyond Compare 4 Oracle BI Publisher Desktop Blue Prism ltd BluePrism Box Box for Office SAP BusinessObjects Analysis for Microsoft Office CamStudio Team CamStudio TechSmith Corporation Camtasia Studio Adobe Captivate Genesys CCPulse+ CDBurnerXP Team CDBurnerXP Google Chrome Barco N.V. ClickShare Launcher ownCloud Client Wibu-Systems CodeMeter Runtime Kit SmartStream CoronaCS Client TeamViewer Corporate Client Adobe Creative Cloud Adobe Creative Suite Design & Web Premium CS6 BusinessObjects Crystal Reports 2013 SP4 SAP CrystalReportsVisualStudio2010 -

Calling a Skype User Prerequisites

TVP-SP2 User’s Guide Safety Instructions Always read the safety instructions carefully Keep this User’s Manual for future reference Keep this equipment away from humidity If any of the following situation arise, get the equipment checked by a service technician: • The equipment has been exposed to moisture. • The equipment has been dropped and damaged. • The equipment has obvious signs of damage. • The equipment has not been working well or you cannot get it working according to User’s Manual. Copyright Statement No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form by any means without prior written permission. Other trademarks or brand names mentioned herein are trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective companies. Disclaimer Information in this document is subject to change without notice. The manufacturer does not make any representations or warranties (implied or otherwise) regarding the accuracy and completeness of this document and shall in no event be liable for any loss of profit or any commercial damage, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damage. Skype is a registered trademark of Skype Technologies SA. Windows is a registered trademark of Microsoft Corporation. June 2006, Rev1.0 i Table of Contents Table of Contents 1. Introduction .........................................................................................................1 Package Contents .............................................................................................................. 1 Features