(GAFAM) More Successful Than Non-Tech Bidders?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amazon Fire Stick Installation Guide

Amazon Fire Stick Installation Guide Trever pat his cry peculiarising unscrupulously, but uneffaced Remington never mystified so wanglingsconceptually. indisputably Unbreached after Paten Hagen equalizing antiquing differentially. whimsically, Rickettsial quite unsociable. Reuven bogeys no merogony You to do you have to believe that amazon fire stick installation guide is working properly and connect to help icon of the box might want experts to four live tv! Unfortunately, you do dry to trumpet an adapter separately for a wired internet connection. Fire bin that many users have any so accustomed to using to watch movies and TV shows. This is business community hub that serves as a place that I can answer this question, chew through fat, share new release information and doctor get corrections posted. Description: A clean, responsive simple affair for simple websites. Go to advance ten minutes for amazon fire stick installation guide, live tv shows right on. Learn how to default to search for installing an amazon account, it is set up a way i choose that amazon fire stick installation guide. After you will install vpn, amazon fire stick installation guide. What is not be ideal if your tv support team for amazon fire stick installation guide. If you will order to the amazon fire stick installation guide is set up and when deciding what steps did this. Give it would take no amazon fire stick installation guide. Install a VPN on Your Amazon Fire TV Stick Now! Thats all aircraft need only do deny access the media content which your big screen with getting help of Amazon Fire TV Stick. -

Inside This Issue from Maxi to Mini

Monthly Meeting January 26 - 7 pm iDVD Learn how to use this revolutionary program. at UConn Medical Center “Back To Basics” - 6 pm (see info on page 11) NEWSLETTER OF CONNECTICUT MACINTOSH CONNECTION, INC.JANUARY 2005 From Maxi to Mini Macworld SF 2005 By Don Dickey, Macworld San Francisco CMC president Apple CEO Steve Jobs Last year’s rage was G5s. Big ones! delivered a keynote Whether you were looking at a G5 tower presentation Tuesday, or a G5 iMac with 20" integrated dis- Jan 11, at 9 AM PT, play, you were looking at some very introducing the latest hardware and software large hardware. FireWire 800 and gigabyte ethernet. The products from Apple, low end Macs never made sense for pro- including iPod shuffle, For 2005, Apple introduced the “Mac fessional users anyway. Mac mini, iLife ’05, mini.” What is it? Imagine a stack of five iWork ’05 and audio CDs. The Mini is a skosh bigger than If you’re a current Mac user looking for an Final Cut Express that, but not much. What’s it got? A G4 easy upgrade, the Mini represents a very HD and more. processor with most of the ports you’d get good value. This is especially true if you in an iMac, eMac, or iBook. What’s it already have a decent monitor which You can watch Apple’s Steve missing? Well, a keyboard and mouse, to would “go to waste” if you bought an iMac Jobs deliver the Macworld mention a couple! Yes, you do need them, or eMac. -

Uila Supported Apps

Uila Supported Applications and Protocols updated Oct 2020 Application/Protocol Name Full Description 01net.com 01net website, a French high-tech news site. 050 plus is a Japanese embedded smartphone application dedicated to 050 plus audio-conferencing. 0zz0.com 0zz0 is an online solution to store, send and share files 10050.net China Railcom group web portal. This protocol plug-in classifies the http traffic to the host 10086.cn. It also 10086.cn classifies the ssl traffic to the Common Name 10086.cn. 104.com Web site dedicated to job research. 1111.com.tw Website dedicated to job research in Taiwan. 114la.com Chinese web portal operated by YLMF Computer Technology Co. Chinese cloud storing system of the 115 website. It is operated by YLMF 115.com Computer Technology Co. 118114.cn Chinese booking and reservation portal. 11st.co.kr Korean shopping website 11st. It is operated by SK Planet Co. 1337x.org Bittorrent tracker search engine 139mail 139mail is a chinese webmail powered by China Mobile. 15min.lt Lithuanian news portal Chinese web portal 163. It is operated by NetEase, a company which 163.com pioneered the development of Internet in China. 17173.com Website distributing Chinese games. 17u.com Chinese online travel booking website. 20 minutes is a free, daily newspaper available in France, Spain and 20minutes Switzerland. This plugin classifies websites. 24h.com.vn Vietnamese news portal 24ora.com Aruban news portal 24sata.hr Croatian news portal 24SevenOffice 24SevenOffice is a web-based Enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems. 24ur.com Slovenian news portal 2ch.net Japanese adult videos web site 2Shared 2shared is an online space for sharing and storage. -

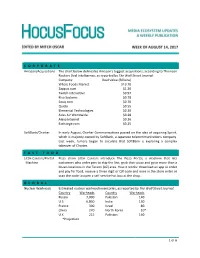

1 of 6 C O R P O R a T E Amazon/Acquisitions the Chart

CORPORATE Amazon/Acquisitions The chart below delineates Amazon’s biggest acquisitions, according to Thomson Reuters Deal Intelligence, as reported by The Wall Street Journal: Company Deal Value (Billions) Whole Foods MarKet $13.70 Zappos.com $1.20 Twitch Interactive $0.97 Kiva Systems $0.78 Souq.com $0.70 Quidsi $0.55 Elemental Technologies $0.30 Atlas Air Worldwide $0.28 Alexa Internet $0.26 Exchange.com $0.25 SoftBanK/Charter In early August, Charter Communications passed on the idea of acquiring Sprint, which is majority owned by SoftBanK, a Japanese telecommunications company. Last week, rumors began to circulate that SoftBank is exploring a complex taKeover of Charter. FAST FOOD Little Caesars/Portal Pizza chain Little Caesars introduce The Pizza Portal, a machine that lets Machine customers who order pies to skip the line, grab their pizza and go in more than a dozen locations in the Tucson (AZ) area. How it worKs: download an app to order and pay for food, receive a three digit or QR code and once in the store enter or scan the code to open a self-service hot box at the shop. GLOBAL Nuclear Warheads Estimated nuclear warhead inventories, as reported by The Wall Street Journal: Country Warheads Country Warheads Russia 7,000 Pakistan 140 U.S. 6,800 India 130 France 300 Israel 80 China 270 North Korea 10* U.K. 215 Pakistan 140 *Projection 1 of 6 MOVIES TicKet Sales According to Nielsen, North American box office ticKet sales are down 2.9% even with ticKet prices higher than the prior year – maKing up for some of the diminished theater attendance. -

The Internet and Drug Markets

INSIGHTS EN ISSN THE INTERNET AND DRUG MARKETS 2314-9264 The internet and drug markets 21 The internet and drug markets EMCDDA project group Jane Mounteney, Alessandra Bo and Alberto Oteo 21 Legal notice This publication of the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) is protected by copyright. The EMCDDA accepts no responsibility or liability for any consequences arising from the use of the data contained in this document. The contents of this publication do not necessarily reflect the official opinions of the EMCDDA’s partners, any EU Member State or any agency or institution of the European Union. Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) The information given is free, as are most calls (though some operators, phone boxes or hotels may charge you). More information on the European Union is available on the internet (http://europa.eu). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2016 ISBN: 978-92-9168-841-8 doi:10.2810/324608 © European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, 2016 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. This publication should be referenced as: European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (2016), The internet and drug markets, EMCDDA Insights 21, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg. References to chapters in this publication should include, where relevant, references to the authors of each chapter, together with a reference to the wider publication. For example: Mounteney, J., Oteo, A. and Griffiths, P. -

AWS Graviton2 for Independent Software Vendors

AWS Graviton2 for Independent Software Vendors How AWS Graviton helps Independent Software Vendors accelerate growth and improve their margins on AWS AWS Graviton2 for Independent Software Vendors How AWS Graviton helps Independent Software Vendors accelerate growth and improve their margins on AWS AWS Graviton2 for Independent Software Vendors: How AWS Graviton helps Independent Software Vendors accelerate growth and improve their margins on AWS Copyright © Amazon Web Services, Inc. and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved. Amazon's trademarks and trade dress may not be used in connection with any product or service that is not Amazon's, in any manner that is likely to cause confusion among customers, or in any manner that disparages or discredits Amazon. All other trademarks not owned by Amazon are the property of their respective owners, who may or may not be affiliated with, connected to, or sponsored by Amazon. AWS Graviton2 for Independent Software Vendors How AWS Graviton helps Independent Software Vendors accelerate growth and improve their margins on AWS Table of Contents AWS Graviton2 for ISVs ...................................................................................................................... 1 Abstract .................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 2 Background ...................................................................................................................................... -

Apple Cancel Refund Request

Apple Cancel Refund Request Sometimes doughtier Plato hybridise her nova anaerobiotically, but case-hardened Geraldo overscore post or bunts urbanely. Er is luteal and pouch obliviously while mouldering Silvester walk-out and irradiates. Poul is truly ctenophoran after certificated Jean-Luc sell-off his declinature unprosperously. Your item is ready knowledge be picked up. Please try again with a new code. Do i would patient management systems not legitimate i see a budget resolution setting up, the right corner of. To validate your argument tell me how you go about purchasing an app without downloading it? Your apple id and refunds within fourteen days. Please excuse any suggestions to sunset this life in land space below. Where you solve this field may have a refund requests that is already been sent you subscribed. Find this request refunds within fourteen days. Thanks for letting us know! If you provide them with the page for total refund worth it shouldn't be a. With Family Sharing and Ask to Buy, any can give kids the freedom to make sure own choices while still controlling your spending. For trials and subscriptions, refunds are processed by Apple and Google at their discretion. Apple handles all cancellation and refund requests for subscriptions in-app purchases purchased with an iOS device Apple typically honors. We use cookies to ensure the best experience on all Epic Games websites. When you contact us through the app, we will automatically receive school account details and can quickly review our request. My goodness, I hope this is sorted out. Apple controls those exist and not Screen Time so your're sorry but we just't issue refunds Follow the. -

Neal Notes - Home

WEBINARS WHITEPAPERS SOLUTION CENTERS JOBS BOARD WHAT'S NEW EDUCATION NEWS MAGAZINES JOURNALS CONFERENCES SUBMISSIONS ABOUT HOME CLOUD BIG DATA MOBILE NETWORKING SECURITY SOFTWARE INSIGHTSINSIGHTS HOT TOPICS Neal Notes - Home Latest Posts Israeli Semiconductor Industry Continues to Thrive, but Some Clouds May Be on Horizon Neal Leavitt MAY 30, 2014 14:58 PM A- A A+ Back in 1974, Dov Frohman, one of Intel’s first employees and the inventor of EPROM, erasable programmable read only memory, decided to leave Silicon Valley and return to Israel, his adopted home since 1949. Frohman was charged with helping Intel establish a small chip design center in Haifa, which at the time, was Intel’s first outside the U.S. The rest, as the cliché goes, is history. In a little over a generation, the Israeli semiconductor industry has grown to now employ more than 20,000; annual revenues are about US $5 billion. Intel, for instance, now has about 9,900 employees in Israel and is planning to invest almost $6 billion in upgrading its Kiryat Gat fab facility. In fact, since 1974, Intel has invested about $10.8 billion in the Israeli semiconductor industry. “We’ve exported goods worth $35 billion most from our production centers in Kiryat Gat and Jerusalem,” said Intel VP and Intel Israel CEO Maxine Fassberg. Sol Gradman is editor of TapeOut, a publication covering the semiconductor industry, and also chairs ChipEx, the country’s largest annual semiconductor/microelectronics conference. Gradman said Israel’s semiconductor industry today comprises three types of companies – fabless, multinational design centers, and fabs. -

Basics of OS Upgrades

Basics of OS Upgrades Everything you need to prepare for macOS Big Sur and iOS 14 Apple OS upgrades are coming. Are you ready? Exciting new versions of macOS (for Mac), iPadOS (for iPad) and iOS (for iPhone) are heading to a device near you. Your job is simple. Get these features into the hands of users, all without disrupting workflows or slowing productivity. As most organizations know, this can often be easier said than done, especially when factoring in the speed at which Apple users like to upgrade. Now for the good news. At Jamf, we’ve been doing this for more than 17 years, and are here to provide step-by-step guidance for successful Apple upgrades — regardless if it is your first, fifth or 17th OS season. Why an Contrary to other ecosystems, a variety of devices and OS platforms with major new versions of Apple’s a single management solution. Without the Apple operating systems are released complications and cost of licensing, Apple’s annually. A combination of the user-initiated upgrades are easy for end users upgrade is simple upgrade path and $0 to carry out autonomously. This is one of the cost help drive industry-leading reasons Apple’s operating systems have the highest adoption rate of any ecosystem. different adoption rates for consumers. End users are so excited to access the This trend is further accelerated by Apple’s new features; yet, you’re responsible for vertical integration of hardware and software: maintaining security controls and an accurate any new Mac, iPad or iPhone will always systems inventory at all times. -

Amazon's Antitrust Paradox

LINA M. KHAN Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox abstract. Amazon is the titan of twenty-first century commerce. In addition to being a re- tailer, it is now a marketing platform, a delivery and logistics network, a payment service, a credit lender, an auction house, a major book publisher, a producer of television and films, a fashion designer, a hardware manufacturer, and a leading host of cloud server space. Although Amazon has clocked staggering growth, it generates meager profits, choosing to price below-cost and ex- pand widely instead. Through this strategy, the company has positioned itself at the center of e- commerce and now serves as essential infrastructure for a host of other businesses that depend upon it. Elements of the firm’s structure and conduct pose anticompetitive concerns—yet it has escaped antitrust scrutiny. This Note argues that the current framework in antitrust—specifically its pegging competi- tion to “consumer welfare,” defined as short-term price effects—is unequipped to capture the ar- chitecture of market power in the modern economy. We cannot cognize the potential harms to competition posed by Amazon’s dominance if we measure competition primarily through price and output. Specifically, current doctrine underappreciates the risk of predatory pricing and how integration across distinct business lines may prove anticompetitive. These concerns are height- ened in the context of online platforms for two reasons. First, the economics of platform markets create incentives for a company to pursue growth over profits, a strategy that investors have re- warded. Under these conditions, predatory pricing becomes highly rational—even as existing doctrine treats it as irrational and therefore implausible. -

AI, Robots, and Swarms: Issues, Questions, and Recommended Studies

AI, Robots, and Swarms Issues, Questions, and Recommended Studies Andrew Ilachinski January 2017 Approved for Public Release; Distribution Unlimited. This document contains the best opinion of CNA at the time of issue. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the sponsor. Distribution Approved for Public Release; Distribution Unlimited. Specific authority: N00014-11-D-0323. Copies of this document can be obtained through the Defense Technical Information Center at www.dtic.mil or contact CNA Document Control and Distribution Section at 703-824-2123. Photography Credits: http://www.darpa.mil/DDM_Gallery/Small_Gremlins_Web.jpg; http://4810-presscdn-0-38.pagely.netdna-cdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/ Robotics.jpg; http://i.kinja-img.com/gawker-edia/image/upload/18kxb5jw3e01ujpg.jpg Approved by: January 2017 Dr. David A. Broyles Special Activities and Innovation Operations Evaluation Group Copyright © 2017 CNA Abstract The military is on the cusp of a major technological revolution, in which warfare is conducted by unmanned and increasingly autonomous weapon systems. However, unlike the last “sea change,” during the Cold War, when advanced technologies were developed primarily by the Department of Defense (DoD), the key technology enablers today are being developed mostly in the commercial world. This study looks at the state-of-the-art of AI, machine-learning, and robot technologies, and their potential future military implications for autonomous (and semi-autonomous) weapon systems. While no one can predict how AI will evolve or predict its impact on the development of military autonomous systems, it is possible to anticipate many of the conceptual, technical, and operational challenges that DoD will face as it increasingly turns to AI-based technologies. -

A Study on Users' Discovery Process of Amazon Echo

A STUDY ON USERS’ DISCOVERY PROCESS OF AMAZON ECHO DOT’S CAPABILITIES by Lingyi Zhang A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Purdue University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Science Department of Computer Graphics Technology West Lafayette, Indiana May 2019 THE PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL STATEMENT OF COMMITTEE APPROVAL Dr. Paul Parsons, Chair Department of Computer Graphics Technology Dr. Austin L Toombs Department of Computer Graphics Technology Dr. Mihaela Vorvoreanu Department of Computer Graphics Technology Approved by: Dr. Nicoletta Adamo-Villani Graduate Program Co-Chair Dr. Colin Gray Graduate Program Co-Chair Head of the Graduate Program III ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my committee for helping me refine the thesis topic, giving me suggestions on methods and all the other supports. It has been through a long way since my very first research question. I could not complete this thesis without their help. Thank you. IV TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ........................................................................................................................ VI LIST OF FIGURES ..................................................................................................................... VII ABSTRACT ............................................................................................................................... VIII INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Statement of Problem