The Indian National Army: a Force for Nationalism?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SPARROW Newsletter

SNL Number 38 May 2019 SPARROW newsletter SOUND & PICTURE ARCHIVES FOR RESEARCH ON WOMEN A Random Harvest: A book of Diary sketches/ Drawings/Collages/ Watercolours of Women Painters It is a random collection from the works women painters who supported the Art Raffle organised by SPARROW in 2010. The works were inspired by or were reflections of two poems SPARROW gave them which in our view, exemplified joy and sorrow and in a sense highlighted women’s life and experiences that SPARROW, as a women’s archives, has been documenting over the years. Contribution Price: Rs. 350/- This e-book is available in BookGanga.com. Photographs............................................. 19267 Ads................................................................ 7449 Books in 12 languages............................ 5728 Newspaper Articles in 8 languages... 31018 Journal Articles in 8 languages..............5090 Brochures in 9 languages........................2062 CURRENT Print Visuals................................................. 4552 Posters........................................................... 1772 SPARROW Calendars...................................................... 129 Cartoons..............................................................3629 Maya Kamath’s cartoons...........................8000 HOLDINGS Oral History.................................................. 659 Video Films................................................. 1262 Audio CDs and Cassettes...................... 929 Private Papers........................................ -

The Second African International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management

IEOM The Second African International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management December 7-10, 2020 Host: Harare, Zimbabwe University of Zimbabwe Industrial Engineering and Operations Management Society International 21415 Civic Center Dr., Suite 217, Southfield, Michigan 48076, USA IEOM Harare Conference December 7-10, 2020 Sponsors and Partners Organizer IEOM Society International Industrial Engineering and Operations Management Society International 21415 Civic Center Dr., Suite 217, Southfield, Michigan 48076, USA, p. 248-450-5660, e. [email protected] Welcome to the 2nd African IEOM Society Conference Harare, Zimbabwe To All Conference Attendees: We want to welcome you to the 2nd African IEOM Society Conference in Harare, Zimbabwe hosted by the University of Zimbabwe, December 7-10, 2020. This unique international conference provides a forum for academics, researchers, and practitioners from many industries to exchange ideas and share recent developments in the fields of industrial engineering and operations management. This diverse international event provides an opportunity to collaborate and advance the theory and practice of significant trends in industrial engineering and operations management. The theme of the conference is “Operational Excellence in the Era of Industry 4.0.” There were more than 400 papers/abstracts submitted from 43 countries, and after a thorough peer review process, approximately 300 have been accepted. The program includes many cutting-edge topics of industrial engineering and operations management. Our keynote speakers: • Prof. Kuzvinetsa Peter Dzvimbo, Chief Executive Officer, Zimbabwe Council for Higher Education (ZIMCHE), Harare, Zimbabwe • Dr. Esther T. Akinlabi, Director, Pan African University for Life and Earth Sciences Institute (PAULESI), Ibadan, Nigeria - African Union Commission • Henk Viljoen, Siemens – Xcelerator, Portfolio Development Manager Siemens Digital Industries Software, Pretoria, Gauteng, South Africa • Dr. -

16-Days-Battle-Of-Imphal-And-Burma

Overview “The war in Burma was a combination of jungle war, mountain war, desert war, and naval war” – Colonel Fuwa Masao, Burma: The Longest War (by Louis Allen) "...the Battles of Imphal and Kohima were the turning point of one of the most gruelling campaigns of the Second World War" - National Army Museum, United Kingdom This is the first such battlefield tour on offer that takes in the Burma Campaign sites on both sides of the India- Burma/Myanmar frontier. And it coincides with the 75th Anniversary of the Burma campaign. In an adventurous and thrilling journey of slightly over two weeks, you will visit not only Imphal and Kohima in North east India, where some of the decisive battles of the campaign were fought but also the main battlefields in Burma/Myanma. It is an unmissable battlefield tour of the Burma Campaign. What makes this particular tour even more special is the overland crossing of the border at Moreh-Tamu - a route rich in Second World War history. An epic clash took place in 1944 during the Second World War between the British 14th Army and the Japanese 15th Army in North East India. Together with the Japanese also came a much smaller force of the Indian National Army (INA). Centred in and around the cities of Imphal and Kohima from March to July of that year, the twin battles of 1944 involved some of the bitterest fighting the world has ever seen. The British military historian Robert Lyman describes Imphal-Kohima as one of the four great turning-point battles of the Second World War, with Stalingrad, El Alamein and Midway being the other three. -

(Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl

MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 1954 1 Dr. Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan BR TN Public Affairs Expired 2 Shri Chakravarti Rajagopalachari BR TN Public Affairs Expired 3 Dr. Chandrasekhara Raman BR TN Science & Eng. Expired Venkata 4 Shri Nand Lal Bose PV WB Art Expired 5 Dr. Satyendra Nath Bose PV WB Litt. & Edu. 6 Dr. Zakir Hussain PV AP Public Affairs Expired 7 Shri B.G. Kher PV MAH Public Affairs Expired 8 Shri V.K. Krishna Menon PV KER Public Affairs Expired 9 Shri Jigme Dorji Wangchuk PV BHU Public Affairs 10 Dr. Homi Jehangir Bhabha PB MAH Science & Eng. Expired 11 Dr. Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar PB UP Science & Eng. Expired 12 Shri Mahadeva Iyer Ganapati PB OR Civil Service 13 Dr. J.C. Ghosh PB WB Science & Eng. Expired 14 Shri Maithilisharan Gupta PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 15 Shri Radha Krishan Gupta PB DEL Civil Service Expired 16 Shri R.R. Handa PB PUN Civil Service Expired 17 Shri Amar Nath Jha PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 18 Shri Malihabadi Josh PB DEL Litt. & Edu. 19 Dr. Ajudhia Nath Khosla PB DEL Science & Eng. Expired 20 Shri K.S. Krishnan PB TN Science & Eng. Expired 21 Shri Moulana Hussain Madni PB PUN Litt. & Edu. Ahmed 22 Shri V.L. Mehta PB GUJ Public Affairs Expired 23 Shri Vallathol Narayana Menon PB KER Litt. & Edu. Expired Wednesday, July 22, 2009 Page 1 of 133 Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 24 Dr. -

Realignment and Indian Air Power Doctrine

Realignment and Indian Airpower Doctrine Challenges in an Evolving Strategic Context Dr. Christina Goulter Prof. Harsh Pant Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed or implied in the Journal are those of the authors and should not be construed as carrying the official sanction of the Department of Defense, Air Force, Air Education and Training Command, Air University, or other agencies or departments of the US government. This article may be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. If it is reproduced, the Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs requests a courtesy line. ith a shift in the balance of power in the Far East, as well as multiple chal- Wlenges in the wider international security environment, several nations in the Indo-Pacific region have undergone significant changes in their defense pos- tures. This is particularly the case with India, which has gone from a regional, largely Pakistan-focused, perspective to one involving global influence and power projection. This has presented ramifications for all the Indian armed services, but especially the Indian Air Force (IAF). Over the last decade, the IAF has been trans- forming itself from a principally army-support instrument to a broad spectrum air force, and this prompted a radical revision of Indian aipower doctrine in 2012. It is akin to Western airpower thought, but much of the latest doctrine is indigenous and demonstrates some unique conceptual work, not least in the way maritime air- power is used to protect Indian territories in the Indian Ocean and safeguard sea lines of communication. Because of this, it is starting to have traction in Anglo- American defense circles.1 The current Indian emphases on strategic reach and con- ventional deterrence have been prompted by other events as well, not least the 1999 Kargil conflict between India and Pakistan, which demonstrated that India lacked a balanced defense apparatus. -

Department of History MODERN COLLEGE, IMPHAL

Department of History MODERN COLLEGE, IMPHAL A. FACULTY BIODATA 1. Personal Profile: Full Name Dr. Pechimayum Pravabati Devi Designation Associate Professor, HOD Date of Birth 01-03-1961 Date of Joining Service 12-10-1990 Subject Specialisation Ancient Indian History Qualification M.A. Ph. D Email [email protected] Contact Number +91 9436284578 Full Name Dr. Moirangthem Imocha Singh Designation Assistant Professor Date of Birth 01-10-1968 Date of Joining Service 16-01-2009 Subject Specialisation Mordern Indian History Qualification M.A. Ph. D Email [email protected] Contact Number 9856148957 Full Name Takhellambam Priya Devi Designation Assistant Professor Date of Birth 10-03-1968 Date of Joining Service 10-05-2016 Subject Specialisation Ancient Indian History Qualification M.A. M. Phil Email [email protected] Contact Number 9862979880 B. Evaluative Report General Information: History Department was open from the establishment of this College since 1963 till today. At present, our Department has three faculty members. Every year around 400 students enrolled in our Department. Sanctioned seat for honours course is 100 of which around 60 students offer honourse. Pass percentage of our Department ranges between 60 to 70 percent. Unit test in the University question pattern are held for every semester, twice for honours students and once for general students. Seminars are compulsory for Honourse students of 5th and 6th semester. Unit test and seminars are not in the ordinance of Manipur University. But in our college, these seminars and unit test are compulsory and held for the betterment of the students. Academic Activity: Faculty members are regularly participated in various academic activities like orientation, refresher course, seminars on international and national level, published books, and presented papers in journals. -

Persons – 2012

Persons – 2012 • Omita Paul appointed as the Secretary of the President: Appointment Committee of the Cabinet(ACC) appointed Omita Paul as the Secretary of the President on 24 July 2012. Her tenure as Secretary to the President is for contract basis. Omita is 63 years old. She replaced Christy L Fernandez. Omita Paul was appointed as the information commissioner in the central Information Commission in the year 2009 for the short duration of time at the end of the UPA-I government’s tenure. In addition, she had resigned to join as the Advisor in Finance Ministry from 2004 to 2009. Omita is a retired officer from Indian Information Service (IIS) from 1973 batch. Omita Paul is the wife of KK Paul. KK Paul was the former Delhi Police Commissioner. He is working as the member of the Union Public Service Commission. • Hesham Kandil Named Egypt's New Prime Minister: Egypt’s President Mohamed Morsi elected fifty-year- old Hisham Kandil as the country’s Prime Minister on 26 July. Morsi ordered the country’s former minister of water resources and irrigation, Kandil to form a new government. Kandil, holds an engineering degree from Cairo University in the year 1984 and a Ph.D. from the University of North Carolina in the year 1993. Kandil will be the first Egyptian prime minister to wear a beard, which is a sure sign of change in the country. A number of more experienced names were suggested for the prestigious role, but Morsi chose Kandil, a relatively lesser-known face as the Prime Minister of the country, this could be because he wanted someone unlikely to threaten or overshadow him. -

DEFAULTER PART-A.Xlsx

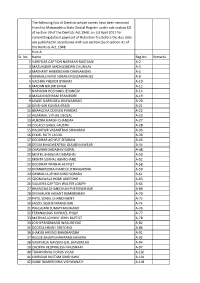

The following lists of Dentists whose names have been removed from the Maharashtra State Dental Register under sub-section (2) of section 39 of the Dentists Act,1948, on 1st April 2017 for committing default payment of Retention fee before the due date are published in accordance with sub section (5) of section 41 of the Dentists Act, 1948. Part-A Sr. No. Name Reg.No. Remarks 1 VARIFDAR CAPTION NARIMAN RUSTAMJI A-2 2 MAZUMDAR MADHUSNDAN CHUNILAL A-3 3 MAEHANT HARIKRISHAN DHANAMDAS A-5 4 GINWALS MINO SORABJI NUSSAWANJEE A-9 5 VACHHA PHEROX BYRAMJI A-10 6 MADAN BALBIR SINGH A-12 7 NARIMAN HOSHANG JEHANGIV A-14 8 MASANI BEHRAM FRAMRORE A-19 9 JAWLE NARENDEA BHAWANRAO A-20 10 DINSHAW KAVINA ERAEH A-21 11 BHARUCHA COOVER PHIRORE A-22 12 AGARWAL VITHAL DEOLAL A-23 13 AURORA HARISH CHANDAR A-27 14 COLACO ISABEL FAUSTIN A-28 15 HALDIPWR VASANTRAO SHAMRAO A-33 16 EEKIEL RUTH JACOB A-39 17 DEODHAR ACHYUT SITARAM A-43 18 DESIAI BHAGWENTRAI GULABSHAWEAR A-44 19 CHAVHAN SADASHIV GOPAL A-48 20 MISTRI JEHANGIR DADABHAI A-50 21 MEHTA SUKHAL ABHECHAND A-52 22 DEODHAR PRABHA ACHYUT A-58 23 DHANBHOORA MANECK JEHANGIRSHA A-59 24 GINWALLA JEHMI MINO SORABJI A-61 25 SOONAWALA HOMI ARDESHIR A-63 26 SIGUEIRA CAPTION WALTER JOSEPH A-65 27 BHANICHA DHANJISHAH PHERIZWSHAW A-66 28 DESHMUKH VASANT RAMKRISHAN A-70 29 PATIL SONAL CHANDHAKNT A-72 30 JAGOS JASSI BYARANSHAW A-74 31 PAHLAJANI SUMATI MUKHAND A-76 32 FERANANDAS RUPHAEL PHILIP A-77 33 MATHIAS JOHNNY JOHN BAPTIST A-78 34 JOSHI PANDMANG WASUDEVAO A-82 35 DCOSTA HENNY SERTORIO A-86 36 JHAKUR ARVIND BHAKHANDRA -

Pan-Asianism: Rabindranath Tagore, Subhas Chandra Bose and Japan’S Imperial Quest

Karatoya: NBU J. Hist. Vol. 11 ISSN: 2229-4880 Pan-Asianism: Rabindranath Tagore, Subhas Chandra Bose and Japan’s Imperial Quest Mary L. Hanneman 1 Abstract Bengali intellectuals, nationalists and independence activists played a prominent role in the Indian independence movement; many shared connections with Japan. This article examines nationalism in the Indian independence movement through the lens of Bengali interaction with Japanese Pan-Asianism, focusing on the contrasting responses of Rabindranath Tagore and Subhas Chandra Bose to Japan’s Pan-Asianist claims . Key Words Japan; Pan-Asianism; Rabindranath Tagore; Subhas Chandra Bose; Imperialism; Nationalism; Bengali Intellectuals. Introduction As Japan pursued military expansion in East Asia in the 1930s and early 1940s, it developed a Pan-Asianist narrative to support its essentially nationalist ambitions in a quest to create an “Asia for the Asiatics,” and to unite all of Asia under “one roof”. Because it was backed by military aggression and brutal colonial policies, this Pan- Asianist narrative failed to win supporters in East Asia, and instead inspired anti- Japanese nationalists throughout China, Korea, Vietnam and other areas subject to Japanese military conquest. The Indian situation, for various reasons which we will explore, offered conditions quite different from those prevailing elsewhere in Asia writ large, and as a result, Japan and Indian enjoy closer and more cordial relationship during WWII and its preceding decades, which included links between Japanese nationalist thought and the Indian independence movement. 1 Phd, Modern East Asian History, University of Washington, Tacoma, Fulbright –Nehru Visiting Scholar February-May 2019, Department of History, University of North Bengal. -

India's Independence in International Perspective Author(S): Sugata Bose Source: Economic and Political Weekly, Vol

Nation, Reason and Religion: India's Independence in International Perspective Author(s): Sugata Bose Source: Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 33, No. 31 (Aug. 1-7, 1998), pp. 2090-2097 Published by: Economic and Political Weekly Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4407049 . Accessed: 29/06/2011 13:46 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at . http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=epw. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Economic and Political Weekly is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Economic and Political Weekly. http://www.jstor.org SPECIAL ARTICLES Nation, Reason and Religion India's Independencein InternationalPerspective Sugata Bose Throughout the entire course of the history of Indian anti-colonialism, religion as faith within the limits of morality, if not the limits of reasona, had rarely impeded the cause of national unity and may in fact have assisted its realisatioin at key nmomentsof struggle. -

History: India Ww2: Essay Question

HISTORY: INDIA WW2: ESSAY QUESTION Question: how accurate is it to say that the Second World War was the most significant factor driving Indian nationalism in the years 1935 to 1945. (20) One argument for why the Second World War was the most significant factor in driving Indian Nationalism from 1935 to 1945 is because Britain spent vast amounts of money on the Indian army, £1.5 million per year, which made the Indian army feel a boost of self-worth and competence. This would have had a significant effect of Indian nationalism as competence and self- belief are essential in nationalism. Furthermore, Britain paid for most of the costs of Indian troops who fought in North Africa, Italy and elsewhere. This allowed the Indian government to build up a sterling balance of £1,300 million in the reserve Bank of India. This gave Indians freedom of how to spend it which could be spent on new Indian businesses or on infrastructure. This in turn, boosted nationalism as it showed India was becoming less reliant on Britain. However, while India did benefit economically in some aspects from the war, the divisions between Congress and the Muslim League grew. One example of how this occurred could be because the 1937 elections marginalised the Muslim League which made them seem like true nationalists. Once WW2 started these divisions grew as Jinnah returned as a stronger leader wanting better protection of Muslims. As a result, World War Two drove nationalism because of the financial effects on India but increased Muslim nationalism by driving a wedge between the Muslims and Hindus. -

Genesis of the Indian National Army Dr

Genesis of the Indian National Army Dr. Harkirat Singh Associate Professor, Head, Department of History, Public College, Samana (Punjab), INDIA- 147201, [email protected], 9815976415 Abstract: The efforts of Indians to promote the cause of India’s independence from abroad occupy a unique place in the history of Indian struggle for freedom. The history of the Indian National Army, under which Indian had struggled for independence of India from outside, is the great story of a revolutionary war against the British colonial Government in India, with the help of the Japanese. It was the culmination of the great struggle for Indian independence from outside the country. Though at times it encountered the difficulties, it was to leave mark of eternal glory under the very able leadership of Subhas Chandra Bose. Its genesis had interested chapter of Indian history. Keywords: Ghadar, Indian Independence League, Azad Hind Sangh, IGHQ, White Masters Introduction The genesis of the Indian National Army (INA) in East Asia is a fascinating chapter of the Indian freedom movement. During the Second World War, an army for the liberation of India, the Indian National Army was raised in South-East Asia by Gen. Mohan Singh with the help of many Indian civilians and prisoners of war. Regarding the genesis of INA, there are interesting facts which needed to be studied. In this paper an attempt has been made to explore in detail all aspects of the genesis of the INA. To write the paper primary sources, especially INA Files, have been extensively consulted. It was during the latter half of 19th century and in the beginning of 20th century that many Indians left India for greener pastures abroad.