Native Americans and the Legacy of Harry S. Truman Native Americans and the Legacy of Harry S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Truman, Congress and the Struggle for War and Peace In

TRUMAN, CONGRESS AND THE STRUGGLE FOR WAR AND PEACE IN KOREA A Dissertation by LARRY WAYNE BLOMSTEDT Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2008 Major Subject: History TRUMAN, CONGRESS AND THE STRUGGLE FOR WAR AND PEACE IN KOREA A Dissertation by LARRY WAYNE BLOMSTEDT Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Chair of Committee, Terry H. Anderson Committee Members, Jon R. Bond H. W. Brands John H. Lenihan David Vaught Head of Department, Walter L. Buenger May 2008 Major Subject: History iii ABSTRACT Truman, Congress and the Struggle for War and Peace in Korea. (May 2008) Larry Wayne Blomstedt, B.S., Texas State University; M.S., Texas A&M University-Kingsville Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Terry H. Anderson This dissertation analyzes the roles of the Harry Truman administration and Congress in directing American policy regarding the Korean conflict. Using evidence from primary sources such as Truman’s presidential papers, communications of White House staffers, and correspondence from State Department operatives and key congressional figures, this study suggests that the legislative branch had an important role in Korean policy. Congress sometimes affected the war by what it did and, at other times, by what it did not do. Several themes are addressed in this project. One is how Truman and the congressional Democrats failed each other during the war. The president did not dedicate adequate attention to congressional relations early in his term, and was slow to react to charges of corruption within his administration, weakening his party politically. -

Setting a New Course in Native American Protest Movements: the Menominee Warrior Society’S Takeover of the Alexian Brothers Novitiate in 1975

Setting a New Course in Native American Protest Movements: The Menominee Warrior Society’s Takeover of the Alexian Brothers Novitiate in 1975 Rachel Lavender Capstone Advisor: Dr. Patricia Turner Cooperating Professors: Dr. Andrew Sturtevant and Dr. Heather Ann Moody History 489 December, 2017 Copyright for this work is owned by the author. This digital version is published by McIntyre Library, University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire with the consent of the author. Table of Contents Table of Contents……………………………………………………………………….. Pg. 1 Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………. Pg. 2 Acknowledgments………………………………………………………………………. Pg. 3 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………... Pg. 4 Secondary Literature……………………………………………………………………. Pg. 7 Long Term Causes: Menominee Termination and D.R.U.M.S…………..…………….. Pg. 14 Trigger………………………………………………………………………………….. Pg. 20 The Takeover: A Collision of Tactics Ada Deer and Legislative Change……………………………………………… Pg. 22 The Menominee Warrior Society and Direct Action…………………………… Pg. 27 After Gresham: Conclusion…………………………………………………………….. Pg. 30 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………. Pg. 35 1 Abstract Abstract: In the 1960s and 1970s, the United States experienced multiple Native American protest movements. These movements came from two different methods of protest: direct action, or grassroots tactics, and long-term political strategies.. The first method, grassroots tactics, was exemplified by groups such as the American Indian Movement and the Menominee Warrior Society. The occupations of Alcatraz Wounded Knee and the BIA, as well as the takeover of the Alexian Brothers Novitiate all represented the use of grassroots tactics. The second method of protest was that of peaceful change through legislation, or political strategies. The D.R.U.M.S. movement, the Menominee Restoration Committee and the political activism of Ada Deer all represented the use of political strategies. -

Chapter Twenty-Six the Cold War, 1945–1952

CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX THE COLD WAR, 1945–1952 CHAPTER OVERVIEW This chapter covers the beginnings of the Cold War under the Truman presidency as it affected both foreign and domestic policies. Peace after World War II was marred by a return to the 1917 rivalry of the United States and the Soviet Union. Truman and his advisors introduced the basic Cold War policies of containment in the Truman Doctrine, the Marshall Plan and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. With the victory of the communists in China and the outbreak of the Korean War, America extended the Cold War to Asia as well. The Cold War prompted the U.S. to rebuild its World War II enemies, Germany and Japan, as counterweights to the Soviets. At home, Americans wanted to return to normal by bringing the troops back home, spending for consumer goods and re-establishing family life, but many changing social patterns brought anxieties. A second Red Scare was caused by the Cold War rhetoric of a bipartisan foreign policy and Truman’s loyalty program, but Senator Joseph McCarthy’s tactics symbolized the era. Defense spending increased and the American economy became depend- ent on it to maintain recovery. Truman tried to extend elements of the New Deal in his Fair Deal but with minimal success. CHAPTER OBJECTIVES After reading the chapter and following the study suggestions given, students should be able to: 1. Illustrate the effects of the Red Scare by discussing the college campus community after World War II. 2. Trace the development of the American policy of containment as applied to Europe and to Asia. -

Conservative Movement

Conservative Movement How did the conservative movement, routed in Barry Goldwater's catastrophic defeat to Lyndon Johnson in the 1964 presidential campaign, return to elect its champion Ronald Reagan just 16 years later? What at first looks like the political comeback of the century becomes, on closer examination, the product of a particular political moment that united an unstable coalition. In the liberal press, conservatives are often portrayed as a monolithic Right Wing. Close up, conservatives are as varied as their counterparts on the Left. Indeed, the circumstances of the late 1980s -- the demise of the Soviet Union, Reagan's legacy, the George H. W. Bush administration -- frayed the coalition of traditional conservatives, libertarian advocates of laissez-faire economics, and Cold War anti- communists first knitted together in the 1950s by William F. Buckley Jr. and the staff of the National Review. The Reagan coalition added to the conservative mix two rather incongruous groups: the religious right, primarily provincial white Protestant fundamentalists and evangelicals from the Sunbelt (defecting from the Democrats since the George Wallace's 1968 presidential campaign); and the neoconservatives, centered in New York and led predominantly by cosmopolitan, secular Jewish intellectuals. Goldwater's campaign in 1964 brought conservatives together for their first national electoral effort since Taft lost the Republican nomination to Eisenhower in 1952. Conservatives shared a distaste for Eisenhower's "modern Republicanism" that largely accepted the welfare state developed by Roosevelt's New Deal and Truman's Fair Deal. Undeterred by Goldwater's defeat, conservative activists regrouped and began developing institutions for the long haul. -

Clifton Truman Daniel's Visit to Oak Ridge and Y‐12, Part 2

Clifton Truman Daniel’s visit to Oak Ridge and Y‐12, part 2 President Harry S. Truman’s grandson, Clifton Truman Daniel, after visiting Japan to attend an anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, recently visited Oak Ridge to learn the history of the place where the uranium 235 was separated for Little Boy, the world’s first atomic bomb used in warfare, and the world’s first uranium reactor to produce plutonium. He also wanted to understand the history of Oak Ridge since the Manhattan Project. It was this uranium 235 and the plutonium from Hanford, WA, that resulted in President Truman’s decision to use atomic bombs to end World War II. This momentous decision accepted as necessary to stop the horrible killing of World War II by Truman has been called the most controversial decision in history. Clifton was six years old before he realized that his “grandpa” had actually been president of the United States and was only 15 years old when former President Harry S. Truman died. Yet, he has taken an active role in the Harry S. Truman Library and Museum as honorary Chair of the Board of Directors. It is an important function that he says he is proud to fulfill. He has also written two books about his famous grandfather and now has accepted a grant to write another book that goes well beyond President Truman’s life to the study of the long‐term impact of his decision to use atomic bombs to end World War II. This project is what brought him to Oak Ridge and will take him to other Manhattan Project sites as well as other visits to Japan where he will seek survivors of the atomic bombs or their families and seek to understand their stories. -

19856492.Pdf

The Harry S. Truman Library Institute, a 501(c)(3) organization, is dedicated to the preservation, advancement, and outreach activities of the Harry S. Truman Library and Museum, one of our nation’s 12 presidential libraries overseen by the National Archives and Records Administration. Together with its public partner, the Truman Library Institute preserves the enduring legacy of America’s 33rd president to enrich the public’s understanding of history, the presidency, public policy, and citizenship. || executive message DEAR COLLEAGUES AND FRIENDS, Harry Truman’s legacy of decisive and principled leadership was frequently in the national spotlight during 2008 as the nation noted the 60th anniversaries of some of President Truman’s most historic acts, including the recognition of Israel, his executive order to desegregate the U.S. Armed Forces, the Berlin Airlift, and the 1948 Whistle Stop campaign. We are pleased to share highlights of the past year, all made possible by your generous support of the Truman Library Institute and our mission to advance the Harry S. Truman Library and Museum. • On February 15, the Truman Library opened a new exhibit on Truman’s decision to recognize the state of Israel. Truman and Israel: Inside the Decision was made possible by The Sosland Foundation and The Jacob & Frances O. Brown Family Fund. A traveling version of the exhibit currently is on display at the Harry S. Truman Institute for the Advancement of Peace, The Hebrew University, Jerusalem, Israel. • The nation bade a sad farewell to Margaret Truman Daniel earlier this year. A public memorial The Harry S. Truman service was held at the Truman Library on February 23, 2008; she and her husband, Clifton Daniel, were laid to rest in the Courtyard near the President and First Lady. -

Harry S. Truman and the Fight Against Racial Discrimination

“Everything in My Power”: Harry S. Truman and the Fight Against Racial Discrimination by Joseph Pierro Thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History Peter Wallenstein, Chairman Crandall Shifflett Daniel B. Thorp 3 May 2004 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: civil rights, discrimination, equality, race, segregation, Truman “Everything in My Power”: Harry S. Truman and the Fight Against Racial Discrimination by Joseph Pierro Abstract Any attempt to tell the story of federal involvement in the dismantling of America’s formalized systems of racial discrimination that positions the judiciary as the first branch of government to engage in this effort, identifies the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision as the beginning of the civil rights movement, or fails to recognize the centrality of President Harry S. Truman in the narrative of racial equality is in error. Driven by an ever-increasing recognition of the injustices of racial discrimination, Truman offered a comprehensive civil rights program to Congress on 2 February 1948. When his legislative proposals were rejected, he employed a unilateral policy of action despite grave political risk, and freed subsequent presidential nominees of the Democratic party from its southern segregationist bloc by winning re-election despite the States’ Rights challenge of Strom Thurmond. The remainder of his administration witnessed a multi-faceted attack on prejudice involving vetoes, executive orders, public pronouncements, changes in enforcement policies, and amicus briefs submitted by his Department of Justice. The southern Democrat responsible for actualizing the promises of America’s ideals of freedom for its black citizens is Harry Truman, not Lyndon Johnson. -

1950'S Presentation

Truman’s Fair Deal: • 81st Congress did not embrace his deal • Did raise minimum wage from 40 to 75 cents/hr • Repeal of Taft-Hartley Act: a law that restricted labor unions • Approved expansion of Social Security coverage and raised Social Security benefits • Passed National Housing Act of 1949; provided housing for low-income families and increased Federal Housing Administration mortgage insurance. • Did NOT pass national health insurance or to provide CHAPTERS 18 & 19 subsidies for farmers or federal aid for schools 1 2 Truman’s Fair Deal: GI Bill: • Fair Deal was an extension of FDR’s New ’ Deal but he did not have the support in • Official name: Servicemen s congress FDR did. Readjustment Act • Congress felt they were too expensive, too • Provided generous loans to veterans to restrictive to business and economy in help them establish businesses, buy general. homes, & attend college • Majority of both houses for Congress were • New housing was more affordable Republican; Truman is a Democrat during the postwar period than at any other time in American history. • Still in use today!! 3 4 1 22nd Amendment to the U.S. THE COLD WAR Constitution 1951 •CONFLICT BETWEEN THE U.S.S.R. & THE • No person shall be elected to the office of the UNITED STATES WHICH BEGAN AFTER WWII President more than twice, and no person who IN RESPONSE TO COMMUNIST EXPANSION. has held the office of President, or acted as President, for more than two years of a term to •COMMUNISM WAS SEEN AS A MORTAL which some other person was elected President THREAT TO THE EXISTENCE OF THE shall be elected to the office of the President WESTERN DEMOCRATIC TRADITION. -

Menominee Termination and Restoration- an Overview

Menominee Termination And Restoration- An Overview Termination was a program championed by many federal policy makers between the late 1940s and early 1960s. The goal of termination was to end Indian tribes' status as sovereign nations. The program was, in some sense, a step backward in U.S. Indian policy because during the 1930s the Commissioner of Indian affairs, John Collier, wanted to empower Indians and end blatantly racist policies the United States had instituted throughout its history. The crowning achievement of his Collier's tenure was the 1934 Indian Reorganization Act (IRA). The IRA became the centerpiece of what Collier called the "Indian New Deal," and explicitly recognized and encouraged Indian tribes as sovereign nations. IRA allowed Indian communities to write constitutions and organize tribal governments to govern their own internal affairs. Despite this, many congressmen and federal bureaucrats disagreed with Collier's program. Prior to Collier, the United States encouraged Indians to give up their cultures and live like "civilized" Whites. Collier left office in 1945, and his departure led these new reformers to feel they could reverse his policies and finish assimilating Indians into American mainstream society. The new reformers' program had many parallels to programs which had existed before Collier, but there were also differences. Reformers of the post-1945 era did not talk about "civilizing" the Indians but spoke instead of "freeing" and "emancipating" Indians from federal control. Goals of Termination Their program had four key goals: • Repealing laws that discriminated against Indians and gave them a different status from other Americans; • Disbanding the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) and transferring its duties to other federal and state agencies or to tribes themselves; • Ending federal supervision of individual Indians; • Ending federal supervision and trust responsibilities for Indian tribes. -

Students Aren't Just Data Points, but Numbers Do Count

LUMINAFOUNDATIONL U M I N A F Winter 2008 Lessons Students aren’t just data points, but numbers do count Lessons: on the inside Page 4 ’Equity for All’ at USC 12 Page Chicago’s Harry S Truman College Page 22 Tallahassee Community College Writing: Christopher Connell Editing: David S. Powell Editorial assistance: Gloria Ackerson and Dianna Boyce Photography: Shawn Spence Photography Design: Huffine Design Production assistance: Freedonia Studios Printing: Mossberg & Company, Inc. On the cover: Indonesia-born Kristi Dewanti attends Tallahassee Community College, where a concerted emphasis on outcomes data is boosting student success. PRESIDENT’SMESSAGE Our grantees wield ‘a powerful tool:’ data Having spent most of the last two decades as a higher education researcher and analyst, I’ve developed some appreciation for the importance and value of student-outcomes data for colleges and universities. Such information is used for a variety of purposes, from informing collaborative action planning on campus, to the actual implementation of those plans, to the assessment or benchmarking of results based on the work undertaken. Robust, reliable data are vital for institutional decision mak- ing and accountability. Compelling data can be the driving force in fostering a “culture of evidence,” leading to measur- able impacts on students and lasting campus change. Too often, casual observers might think that a data-driven institution is one that focuses mainly on the processes of collection and analysis. But at Lumina Foundation for Education, we have always considered data a power- ful tool to better meet students’ needs. From the Achieving the Dream initiative – which has done ground- breaking work to support data-driven decision making at community col- leges – to the important results that have been attained at minority-serving institutions under the Building Engagement and Attainment for Minority Stu- dents (BEAMS) project, Lumina’s investments in data-driven campus change have been gratifying. -

Ch.41 – Peace, Prosperity, Progress EQ

Ch.41 – Peace, Prosperity, Progress EQ: Why are the 1950s remembered as an age of affluence? 41.0: Preview (answer in IAN) 40.1: Coach Schroeder reads introduction 40.2-7: Read Textbook – create a chart. 40.2-7: Cut out Picture – Create a Headline – Use example on your handout. Only have to do 2 BULLETS, BUT AS USUAL I WILL BE DOING ALL OF THEM. Section 2: POSTWAR POLITICS: READJUSTMENTS AND CHALLENGES Postwar Politics: Readjustments and Headline: Challenges; Truman Battles a Republican Congress • Truman has announced a set of reforms called the Fair Deal, including calls to raise the minimum wage and enact a national health insurance program. • With rising prices and growing unemployment, workers in major industries are calling for wage increases and are striking if their demands are not met. • In response to the strikes, Congress has passed the Taft-Hartley Act, limiting the power of labor unions. • The Taft-Hartley Act outlaws the closed shop, or a workplace in which the employer agrees to hire only members of a certain union. It also bans sympathy strikes by other unions. An Upset Victory in 1948 Headline: • Truman’s whistle-stop tour has helped him win reelection in a narrow victory over Thomas Dewey. • Most of Truman’s Fair Deal reforms have been blocked by Congress. • Congress has enacted Truman’s proposal to raise the minimum wage and to promote slum clearance. Ike Take the Middle of the Road Headline: • The nation has decided they “like Ike” and his modern Republicanism program, since they voted him into office. -

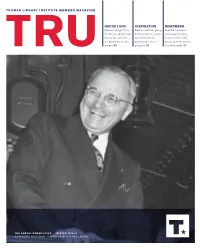

Inside Look Inspiration Remember

TrumanLibrary.org TRUMAN LIBRARY INSTITUTE INSIDE LOOK INSPIRATION REMEMBER Preview highlights from Meet an ambitious young Read the hometown the Truman Library’s new historian who has grown newspaper’s inspiring Korean War collection up with the Truman memorial to the 33rd in a behind-the-scenes Library’s educational president on the anniver- glimpse. 06 programs. 08 sary of his death. 10 THE ANNUAL DONOR ISSUE WINTER 2018-19 ADVANCING PRESIDENT TRUMAN’S LIBRARY AND LEGACY TRU MAGAZINE THE ANNUAL DONOR ISSUE | WINTER 2018-19 COVER: President Harry S. Truman at the rear of the Ferdinand Magellan train car during Winston Churchill’s visit to Fulton, Missouri, in 1946. Whistle Stop “I’d rather have lasting peace in the world than be president. I wish for peace, I work for peace, and I pray for peace continually.” CONTENTS Highlights 10 12 16 Remembering the 33rd President Harry Truman and Israel Thank You, Donors A look back on Harry Truman’s hometown Dr. Kurt Graham recounts the monumental history A note of gratitude to the generous members and newspaper’s touching memorial of the president. of Truman’s recognition of Israel. donors who are carrying Truman’s legacy forward. TrumanLibraryInstitute.org TRUMAN LIBRARY INSTITUTE 1 MESSAGE FROM EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR 2018 was an auspicious year for Truman anniversaries: 100 years since Captain Truman’s service in World War I and 70 years since some of President Truman’s greatest decisions. These life-changing experiences and pivotal chapters in Truman’s story provided the Harry S. Truman Library and Museum with many meaningful opportunities to examine, contemplate and celebrate the legacy of our nation’s 33rd president.