Prosecution That Earns Community Trust

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Highline Community College Building 8, Student Union Building 2400 S

Highline Community College Building 8, Student Union Building 2400 S. 240th Street Des Moines, WA 98198 Schedule 2:15 pm Welcome and Introduction, SeaTac Municipal Court Judge Elizabeth Bejarano; 2:20 pm Mia Gregerson, House Representative and Mayor, City of SeaTac; Dave Kaplan, Mayor, City of Des Moines; Des Moines Municipal Court Judge Veronica Alicea- Galvan 2:45 pm Comedian John Keister 3:15 pm Judge James Docter, City of Bremerton 3:30 pm Recording Artist Wanz 3:40 pm Dan Satterberg, King County Prosecuting Attorney 4:00 pm Katie Whittier, King County Director for Senator Patty Murray, on behalf of Patty Murray 4:15 pm Comedian Ty Barnett 4:45 pm Norm Rice, President and CEO of the Seattle Foundation, and Former Seattle Mayor 5:00 pm Closing remarks (Schedule subject to change as entertainers are added) Speaker and Entertainer Information Speakers Mia Gregerson http://housedemocrats.wa.gov/roster/rep-mia-gregerson/ http://www.ci.seatac.wa.us/index.aspx?page=90 Before being appointed to the House of Representatives in 2013, and selected as Mayor of the City of SeaTac in 2014, Mia served as a council member and deputy mayor for the City of SeaTac. While on the council she served on the executive board of the Puget Sound Regional Council, on the board of directors for Sound Cities Association and on other regional committees. Mia has been a surgical assistant and business manager in the dental field for more than 16 years. She has degrees from Highline Community college and the University of Washington. Dan Satterberg http://www.kingcounty.gov/Prosecutor.aspx A Seattle area native, Dan is a graduate of Highline High school, the University of Washington, and the University of Washington Law School. -

Uwlaw, Fall 2012, Vol. 66

University of Washington School of Law UW Law Digital Commons Alumni Magazines Law School History and Publications Fall 2012 uwlaw, Fall 2012, Vol. 66 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/alum Part of the Legal Education Commons Recommended Citation uwlaw, Fall 2012, Vol. 66, (2012). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/alum/11 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School History and Publications at UW Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Alumni Magazines by an authorized administrator of UW Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nonprofit Org US Postage 66 PAID L eaders for the Seattle, WA E Permit No. 62 M BOX 353020 SEATTLE, WA 98195-3020 U Global Common Good L 2012 VO 2012 L A F L uw uwlaw uwlaw CALENDAR FALL - WINTER - SPRING 2012 - 2013 law OCTOBER 29 FEBRUARY 8 M ARCH 29 – 30 Betts Patterson Mines T owards Global Food Law: 20th Annual NW Dispute Professor of Law Eric Schnapper, Transatlantic Competition and Resolution Conference FALL 2012 VOLUME 66 Installation & Reception Collaboration Conference A PRIL 24 N OVEMBER 1 FEBRUARY 22 NYC Alumni Breakfast Portland Alumni Reception TEI & UW Law Tax Conference A PRIL 25 N OVEMBER 7 Annual Public Interest Law DC Alumni Reception Senior Alumni Student Presentation Association Benefit Auction M AY 31 JA NUARY 11 – 13 & 26 – 27 FEBRUARY 27 Anchorage Alumni Reception Professional Mediation Skills Pendleton Miller Chair in Law Training Program Stewart Jay, Installation & Reception JUNE 9 UW School of Law Commencement JA NUARY 14 M ARCH 6 Garvey Schubert Barer Professor UW Law Foundation Professor Join us on LinkedIn (search for of Law Kathryn A. -

2018 Gplex Seattle

2018 GPLEX SEATTLE Agenda 1 CONNECTING THE CITY OF BROTHERLY LOVE TO THE EMERALD CITY American Airlines is proud to support the Greater Philadelphia Leadership Exchange. 2 2018 GPLEX SEATTLE CONTENTS 4 WELCOME TO THE 2018 LEADERSHIP EXCHANGE 5 AGENDA 8 REGIONAL EXPLORATIONS 10 SPONSORS 12 ABOUT GREATER SEATTLE 14 By the Numbers 18 A Brief History 20 Population 22 Economy 24 Governance 26 Glossary of Seattle Terms 28 PLENARY SPEAKERS 44 LEADERSHIP DELEGATION 60 ABOUT THE ECONOMY LEAGUE 61 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 62 BOARD OF DIRECTORS 64 ESSENTIAL INFORMATION Agenda 3 WELCOME TO THE 2018 LEADERSHIP EXCHANGE I’m excited to be taking part in my fourth GPLEX—and my first as executive director! I was a GPLEX groupie long before I ever imagined I’d be leading this great organization. In any case, I am thrilled to spend a few days with all of you, the movers and shakers who make Greater Philadelphia, well, great. You are among the most diverse cohort we’ve assembled, across both social identity and sector. In GPLEX’s 13th year, we’re incredibly proud to count an alumni base of nearly 1,000 leaders. Stand tall GPLEXers! As always, the board and staff of the Economy League were very deliberate in choosing this year’s destination; we always seek regions that share similarities to our own in size, economy, etc. That said, Seattle is certainly different from Philadelphia. In 1860, while Philadelphia was one of the world’s largest and most economically vibrant cities, the “workshop of the world,” Seattle’s population was about 200 souls; 100 years later, Philadelphia hit its population peak of two million and then saw 50 years of population decline before the slow and steady growth of the late 1990s to the present. -

The Prosecutor's Post

From: Prosecuting, Attorney [[email protected]] Sent: Thursday, February 09, 2012 9:18 AM To: [email protected] Subject: 2012 Feb: The Prosecutor's Post THE PROSECUTOR’S POST Vol. 5, Issue 1 February 9, 2012 _______________________________________________________________________________ Update: LEAD -- An Innovative Approach to Drug Offenses The King County Prosecuting Attorney's Office (PAO) began a unique partnership with the Seattle Police Department's West Precinct, The Defender Association, the Seattle City Attorney's Office, the King County Executive's Office, and the Belltown Community Leaders to launch LEAD -- Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion -- a new, innovative approach to more effectively deal with low-level drug addicts, dealers, and prostitutes who cycle in and out of King County's jail and criminal justice system. This program, launched in October of 2011 and funded by private grant money, is designed to divert individuals away from repeated arrests and bookings for low-level drug offenses and into immediate treatment services and opportunities. As part of the program, officers on the street have the discretion to take low-level drug offenders to a treatment facility managed by Evergreen Treatment Services, where case managers worked with individuals to offer immediate and longer-term treatment, transitional housing, educational opportunities, and other services geared toward breaking the cycle of addiction. So far, Seattle Police Officers have referred 24 individuals to the program.. In one instance, a case manager helped an individual referred to the program to restore his union status so that he could look for work. In another, a case worker successfully encouraged treatment and regular check-ins for a woman who used to routinely solicit and use drugs in front of local storefronts. -

King County Discovery

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This paper could not have been written without the exceptional help and insight of Prosecuting Attorney Dan Satterberg, Chief Deputy Prosecuting Attorney Mark Larson, Assistant Chief Deputy Prosecuting Attorney Erin Ehlert, Legal Services Supervisor Cheryl Woods, and Legal Services Manager Maureen Galloway. The work by Kristine Hamann, Executive Director of Prosecutors’ Center for Excellence was supported by Grant No.2015-DP-BX-K004 awarded by the Bureau of Justice Assistance/Department of Justice to Justice & Security Strategies. The Bureau of Justice Assistance is a component of the Department of Justice's Office of Justice Programs, which also includes the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the National Institute of Justice, the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, the Office for Victims of Crime, and the SMART Office. Points of view or opinions in these materials are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Table of Contents Electronic Discovery ___________________________________________________________ 1 Overview _________________________________________________________________________ 1 Advantages of Electronic Discovery _________________________________________________________ 1 Challenges of Electronic Discovery __________________________________________________________ 2 Discovery in King County, Washington _____________________________________________ 3 Introduction _______________________________________________________________________ -

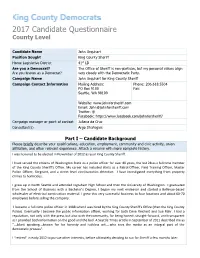

2017 Candidate Questionnaire County Level

2017 Candidate Questionnaire County Level Candidate Name John Urquhart Position Sought King County Sheriff st Home Legislative District 41 LD Are you a Democrat? The Office of Sheriff is non-partisan, but my personal values align Are you known as a Democrat? very closely with the Democratic Party. Campaign Name John Urquhart for King County Sheriff Campaign Contact Information Mailing Address: Phone: 206.618.5504 PO Box 9100 Fax: Seattle, WA 98109 Website: www.johnforsheriff.com Email: [email protected] Twitter: @ Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/johnforsheriff/ Campaign manager or point of contact Juliana da Cruz Consultant(s) Argo Strategies Part I – Candidate Background Please briefly describe your qualifications, education, employment, community and civic activity, union affiliation, and other relevant experience. Attach a resume with more complete history. I was honored to be elected in November of 2012 as your King County Sheriff. I have served the citizens of Washington State as a police officer for over 40 years, the last 28 as a full-time member of the King County Sheriff’s Office. My career has included stints as a Patrol Officer, Field Training Officer, Master Police Officer, Sergeant, and a street level vice/narcotics detective. I have investigated everything from property crimes to homicides. I grew up in North Seattle and attended Ingraham High School and then the University of Washington. I graduated from the School of Business with a Bachelor’s Degree, I began my next endeavor and started a Bellevue-based wholesaler of electrical construction material. I grew this very successful business to four locations and about 60-70 employees before selling the company. -

Washington State Civil Legal Aid Oversight Committee

WASHINGTON STATE CIVIL LEGAL AID OVERSIGHT COMMITTEE MEETING OF MARCH 25, 2016 29TH FLOOR CONFERENCE ROOM KL GATES LLC 925 FOURTH AVE. SEATTLE, WA MEETING MATERIALS CIVIL LEGAL AID OVERSIGHT COMMITTEE MEETING OF MARCH 25, 2016 MEETING MATERIALS Tab 1: Meeting Agenda Tab 2: Draft Minutes of September 18, 2015 Meeting Tab 3: Civil Legal Aid Oversight Committee Mission Tab 4: Civil Legal Aid Oversight Committee Roster Tab 5: Civil Legal Aid Oversight Committee Operating Rules and Procedures Tab 6: Report from the Director of the Office of Civil Legal Aid (with attachments) Tab 7: Draft Resolution 2016-01 March 25, 2016 Meeting Materials -- 1 TAB 1 March 25, 2016 Meeting Materials -- 2 CIVIL LEGAL AID OVERSIGHT COMMITTEE March 25, 2016 10:00 a.m. to 2:00 p.m. KL Gates Law Firm 925 Fourth Ave., 29th Floor Seattle, WA AGENDA 1. Welcome and introductions (Jennifer Greenlee) (10:00 – 10:10) 2. Review and Adopt Minutes of June 12, 2014 Meeting (10:10 – 10:15) 3. Oversight Committee Member Updates (Jim Bamberger, OCLA Director) (10:15 – 10:20) • Appointment of Rep. Drew Stokesbary (House Republican Caucus) • Status of Senate MCC Appointment 4. OCLA Agency Audit (Jim Bamberger) (10:20 – 10:30) ∗ 5. Supplemental Budget Update (Jim Bamberger) (10:30 – 10:40)* 6. Civil Legal Needs Study Update Rollout; Public Positioning of the Conversation Around Civil Legal Aid (Jim Bamberger, Jay Doran) (10:40 – 11:10)* 7. FY 2017-19 Budget Development: The Civil Access to Justice Reinvestment Plan -- Oversight Committee’s Role and Proposed Primary Areas of Investment Focus (Jim Bamberger) (11:10 – 12:00)* Lunch (12:00 – 12:45) (Video from 2-10-16 Supreme Court Symposium on the Civil Legal Needs Study Update) 8. -

Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD): Reducing the Role of Criminalization in Local Drug Control

Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD): Reducing the Role of Criminalization in Local Drug Control July 2015 Many U.S. cities are taking steps to reduce the role Harm Reduction: A Core Principle of LEAD of criminalization in their local drug policies. LEAD is based on a commitment to “a harm reduction Seattle, Washington has been at the forefront of framework for all service provision.”2 Critically, LEAD this effort, pioneering a novel pre-booking does not require abstinence, and clients cannot be diversion program for minor drug law violations sanctioned for drug use or relapse. Instead, LEAD known as Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion recognizes that drug misuse is a complex problem and (LEAD). Santa Fe, New Mexico and several other people need to be reached where they currently are in cities have begun exploring LEAD as a promising their lives. Whether a person is totally abstinent from new strategy to improve public safety and health. alcohol or other drugs matters far less than whether the problems associated with their drug misuse are What is LEAD? getting better or not. Metrics like health, employment After a growing realization that Seattle’s existing and family situation are far more important than the approach to drug law enforcement was a costly failure, outcome of a drug test. the city decided to take a different approach. In 2011, it instituted a pilot program known as “Law Enforcement LEAD acknowledges this reality and incorporates Assisted Diversion,” or LEAD, the first pre-booking these measures – instead of abstinence – into the diversion program in the country. Instead of arresting program’s goals and evaluation, so that participants and booking people for certain nonviolent offenses, are not punished simply for failing a drug test. -

The Necessary Process for Re-Forming the Seattle Police Department

Seattle Journal for Social Justice Volume 13 Issue 1 Article 8 2014 Establishing Legitimacy Through Inclusive Re-Formation: The Necessary Process for Re-Forming the Seattle Police Department Becky Fish Seattle University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.seattleu.edu/sjsj Recommended Citation Fish, Becky (2014) "Establishing Legitimacy Through Inclusive Re-Formation: The Necessary Process for Re-Forming the Seattle Police Department," Seattle Journal for Social Justice: Vol. 13 : Iss. 1 , Article 8. Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.seattleu.edu/sjsj/vol13/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications and Programs at Seattle University School of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Seattle Journal for Social Justice by an authorized editor of Seattle University School of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 189 Establishing Legitimacy Through Inclusive Re-Formation: The Necessary Process for Re-Forming the Seattle Police Department Becky Fish* I. INTRODUCTION People across Seattle expressed outrage a young White Seattle Police Officer, Ian Birk, shot and killed an elderly Native American woodcarver, John T. Williams, on August 30, 2010.1 Mr. Williams was partially deaf and had been standing alone on a street corner holding a piece of wood and a small carving knife.2 Almost six months later, King County Prosecuting Attorney Dan Satterberg held a press conference to announce his decision not to charge Mr. Birk for homicide. Mr. Satterberg pointed to Washington’s statute providing police officers an affirmative defense to * Becky Fish is a third-year law student at Seattle University School of Law and the Editor in Chief of the Seattle Journal for Social Justice. -

District 7 Update January – June 2016

Councilmember Pete von Reichbauer District 7 Update District 7 Update January – June 2016 The first six months of 2016 have been very busy in South King County as I visit with and listen to constituents, work on many issues facing residents and honor those individuals and organizations that help make a difference in our quality of life. Please read on for some of the highlights. kingcounty.gov/vonReichbauer facebook.com/pete.vonreichbauer Councilmember Pete von Reichbauer District 7 Update Working on Behalf of South County Residents on Important Council Initiatives February 15th – The chronic flooding of the White River Estates neighborhood in Pacific has displaced families and disrupted lives. Our urgent action in February allocated $3 million for an expanded containment and barrier line to protect houses and property. By taking the steps we did, we are moving toward providing certainty and peace of mind for these residents. I want to thank the homeowners, many of whom I met at a May 3rd open house in Pacific, who took the time to make their case for a Flood District grant to assist them. Photo from left to right: Flood District Executive Director Kjris Lund, City of Pacific Mayor Leanne Guier and Flood District Chair Reagan Dunn June 29th – As a Flood District Supervisor, I was proud to help kick off new levee work along the White River to reduce the flooding affecting hundreds of homes and thousands of people. I am grateful for the tremendous effort of all parties involved. The Countyline Levy Setback Project is the culmination of extensive public interest, and thousands of research hours by staff. -

Uwlaw, Fall 2009, Vol. 60

University of Washington School of Law UW Law Digital Commons Alumni Magazines Law School History and Publications 10-2009 uwlaw, Fall 2009, Vol. 60 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/alum Part of the Legal Education Commons Recommended Citation uwlaw, Fall 2009, Vol. 60, (2009). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/alum/10 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School History and Publications at UW Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Alumni Magazines by an authorized administrator of UW Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. fall 2009 | volume 60 u wlaw A new era of legal education CALENDAR 2009 – 2010 Alumni receptions with Dean Kellye Y. Testy have been scheduled for the following dates: NOVEMBER 2: New York City NOVEMBER 4: Washington, DC w DECEMBER 8: Portland, OR a JANUARY 28: Tacoma, WA l Please check our alumni website for details (www.law.washington.edu/alumni). 12 w OCTOBER 22 Kellye Y. Testy ushers in a new era of legal Installation of Associate Dean u education as the 14th permanent dean at the Steve Calandrillo as a Charles I. Stone law school. Professor of Law Photo by Matt Hagen. Lecture: Penalizing Punitive Damages: Why the Supreme Court Needs a Lesson UW LAW on Law and Economics Volume 60 Fall 2009 4:00 p.m., William H. Gates Hall, Seattle Reception immediately following DEAN Kellye Y. Testy OCTOBER 30 CLE Program EDITOR Immigration Options for Immigrant Laura Paskin Survivors of Domestic Violence 10:00 a.m. -

FINAL REPORT of the MARIJUANA POLICY REVIEW PANEL on the IMPLEMENTATION of INITIATIVE 75 December 4, 2007

FINAL REPORT OF THE MARIJUANA POLICY REVIEW PANEL ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF INITIATIVE 75 December 4, 2007 Table of Contents Executive Summary iii Acknowledgements v Introduction 1 Legislation 1 The Marijuana Policy Review Panel 2 Findings 4 Implementation of the Ordinance 4 Public Safety 16 Public Administration 19 Public Health 20 Fiscal Impact 28 Conclusions and Recommendations 32 Appendices Appendix 1 Ordinance Number 121509 A-1 Appendix 2 Resolution Number 30648 A-3 Appendix 3 Ordinance Number 122025 A-5 Appendix 4 Memorandum Re: Reporting Criteria for the A-8 Seattle Police Department and City Attorney’s Office Appendix 5 Panel Membership A-11 Appendix 6 Meeting Minutes A-12 Appendix 7 Consultant Curriculum Vitae A-35 i Appendix 8 Marijuana Policy Review Panel Project Scope A-44 for Production of Final Report Appendix 9 Marijuana Policy Review Panel Consultant Tasks, A-47 Deadlines, Costs Appendix 10 Seattle Police Department Complaint Report, A-48 OPA Investigations Section, Case No. IIS-2005-0144 Appendix 11 Marijuana Policy Review Panel Report of Progress A-53 to Seattle City Council ii Executive Summary Initiative 75 (I-75) was passed by Seattle voters in the September 16, 2003 primary election. Its passage resulted in the addition of a new section, 12A.20.060, to the Seattle Municipal Code (SMC). Subsection A stated that “[t]he Seattle Police Department and City Attorney’s Office shall make the investigation, arrest and prosecution of marijuana offenses, when the marijuana was intended for adult personal use, the City’s lowest law enforcement priority.” Subsection B called for the President of the City Council to appoint an eleven- member Marijuana Policy Review Panel “to assess and report on the effects of this ordinance.” Working with a consultant, the Panel collected and analyzed data to address the following questions: 1.