Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The SHRIMP U-Pb Isotope Dating of Mesozoic Volcanic from Zhangwu-Heishan Area, West Liaoning Province, China

EARTH SCIENCES RESEARCH JOURNAL GEOLOGY Earth Sci. Res. J. Vol. 24, No. 4 (December, 2020): 409-417 The SHRIMP U-Pb isotope dating of Mesozoic volcanic from Zhangwu-Heishan Area, West Liaoning Province, China Chaoyong Hou*, Houan Cai, Senlong Pei China Non-ferrous Metals Resource Geological Survey, Beijing 100012, China *Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT Keywords: West Liaoning Province; Zhangwu- The Zhangwu-Heishan area is located in the east of the Fuxin-Yixian basin. Besides the Quaternary soil, the study area Heishan Area; Mesozoic Volcanic Rock; Isotopic is mostly covered with volcanic rock. The horizon and age of volcanic rock play an essential role in understanding Age; Geological Significance. fossil beds, structures, and sedimentary evolution of West Liaoning Province and coal seeking. During this work, 11 volcanic rock samples were measured by SHRIMP U-Pb isotope analysis. Based on the reported data on the age of the Mesozoic volcanic rock in West Liaoning Province, in combination with new measurement data, Cretaceous volcanic activities in West Liaoning Province can be divided into five stages, namely 132±1 Ma, 126±1 Ma, 122±2 Ma, 115±2 Ma, and 100±5 Ma. Based on statistical results, this paper concluded that the thinning time of the crust in Northeast China is from 132±1 Ma to 115±2 Ma. Datación isotópica U-Pb a través de la Microsonda de Iones de Alta-Resolución en rocas volcánicas del Mesozoico para el área Zhangwu-Heishan, en la provincia de Liaoning, en el occidente de China RESUMEN Palabras clave: Provincia Liaoning; área Zhangwu- El área Zhangwu-Heishan se ubica en el este de la cuenca Fuxin-Yixian. -

Pinyin Conversion Project Specifications for Conversion of Name and Series Authority Records October 1, 2000

PINYIN CONVERSION PROJECT SPECIFICATIONS FOR CONVERSION OF NAME AND SERIES AUTHORITY RECORDS OCTOBER 1, 2000 Prepared by the Library of Congress Authorities Conversion Group, February 10, 2000 Annotated with Clarifications from LC March 23, 2000. Contact point: Gail Thornburg Revised, incorporating language suggested by OCLC, as well as adding and changing other sections, April 14, 2000, May 30, 2000, June 20, 2000, June 22, 2000, July 5, 2000, July 27, 2000, August 14, 2000, and September 12, 2000 1 Introduction The conversion, or perhaps better, translation, to PY in our model involves distinct and somewhat arbitrary paths. We employ both specialized dictionaries and strict step-by-step substitution rules for those cases where dictionary substitution proves inadequate. Details of the conversion are given below. This summary seeks to attune the reader to the overall methods and strategy. 1.1 Scope The universe of authority records to be converted (or translated) is determined by scanning headings in the NACO file (i.e., 1xx tags) for character strings matching WG syllables. It is important to understand that this identification plans to, in part, utilize the fixed filed language code in related bibliographic records. The scan is done on a sub-field by sub-field basis for those MARC sub-fields within the heading that could reasonably contain WG strings. Thus, we would scan the heading's sub-field "a" but not sub-field "e" etc. The presence of WG strings in portions of the heading thus acts as a trigger to identify a candidate record for conversion. Once a record has been so identified all other fields that could carry WG data are examined and processed for conversion. -

Chinese Personal Name Disambiguation Based on Vector Space Model

Chinese Personal Name Disambiguation Based on Vector Space Model Qing-hu Fan Hong-ying Zan Yu-mei Chai College of Information Engineering, Yu-xiang Jia Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, College of Information Engineering, Henan ,China Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, [email protected] Henan ,China {iehyzan, ieymchai, ieyx- jia}@zzu.edu.cn Gui-ling Niu Foreign Languages School, Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, Henan ,China [email protected] associate professor at the Department of Me- Abstract chanical and Electrical Engineering, Physics and Electrical and Mechanical Engineering College of Xiamen University, or it may be Peking Uni- versity Founder Group Corp that was established This paper introduces the task of Chinese per- by Peking University. It needs to associate with sonal name disambiguation of the Second context for disambiguating the entity Fang Zheng. CIPS-SIGHAN Joint Conference on Chinese For example, Fang Zheng who is an associate Language Processing (CLP) 2012 that Natural Language Processing Laboratory of professor at Xiamen University can be extracted Zhengzhou University took part in. In this task, with the feature that Xiamen University, Me- we mainly use the Vector Space Model to dis- chanical and Electrical Engineering College or ambiguate Chinese personal name. We extract associate professor, which can eliminate ambigu- different named entity features from diverse ity. names information, and give different weights to various named entity features with the im- 2 Related Research portance. First of all, we classify all the name documents, and then we cluster the documents In the early stages of Named Entity Disambigua- that cannot be mapped to names that have tion, Bagga and Baldwin (1998) use Vector been defined. -

The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier Wai Kit Wicky Tse University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian History Commons, Asian Studies Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Tse, Wai Kit Wicky, "Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier" (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 589. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/589 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/589 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier Abstract As a frontier region of the Qin-Han (221BCE-220CE) empire, the northwest was a new territory to the Chinese realm. Until the Later Han (25-220CE) times, some portions of the northwestern region had only been part of imperial soil for one hundred years. Its coalescence into the Chinese empire was a product of long-term expansion and conquest, which arguably defined the egionr 's military nature. Furthermore, in the harsh natural environment of the region, only tough people could survive, and unsurprisingly, the region fostered vigorous warriors. Mixed culture and multi-ethnicity featured prominently in this highly militarized frontier society, which contrasted sharply with the imperial center that promoted unified cultural values and stood in the way of a greater degree of transregional integration. As this project shows, it was the northwesterners who went through a process of political peripheralization during the Later Han times played a harbinger role of the disintegration of the empire and eventually led to the breakdown of the early imperial system in Chinese history. -

From the Yixian Formation in Northeastern China

An early infructescence Hyrcantha decussata (comb. nov.) from the Yixian Formation in northeastern China David L. Dilcher*†, Ge Sun†‡, Qiang Ji§, and Hongqi Li¶ *Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611; ‡Research Center of Paleontology, Jilin University, Changchun 130026, China; §Geological Institute of Chinese Academy of Geosciences, Beijing 100037, China; and ¶Department of Biology, Frostburg State University, Frostburg, MD 21532 Contributed by David L. Dilcher, April 16, 2007 (sent for review November 10, 2006) The continuing study of early angiosperms from the Yixian For- about half their length. Each carpel containing 10–16 anatrop- mation (Ϸ125 Ma) of northeastern China has yielded a second early ous ovules/seeds borne along an adaxial linear placentae. angiosperm genus. This report is a detailed account of this early flowering plant and recognizes earlier reports of similar fossils H. decussata (Leng et Friis) Dilcher, Sun, Ji et Li comb. nov. from Russia and China. Entire plants, including roots, stems, and Synonymy. S. decussatus Leng et Friis, 2003, 2006. branches terminating in fruits are presented and reconstructed. Emended Description. Plant erect, 20–25 cm tall, with predomi- Evidence for a possible aquatic nature of this plant is presented. nately alternate branching of 30–45°, rarely ternate branching The relationship of Hyrcantha (‘‘Sinocarpus’’) to the eudicots is three to four times (Fig. 1A). Main axis 2.2–2.5 mm wide and discussed. The presence of this second early angiosperm genus, lightly striated alternate branches 1–1.2 mm wide. Lower now known as a whole plant, is important in the discussion of its branches with dilated nodes ensheathed by a thin ocrea (Fig. -

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level Corresponding Type Chinese Court Region Court Name Administrative Name Code Code Area Supreme People’s Court 最高人民法院 最高法 Higher People's Court of 北京市高级人民 Beijing 京 110000 1 Beijing Municipality 法院 Municipality No. 1 Intermediate People's 北京市第一中级 京 01 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Shijingshan Shijingshan District People’s 北京市石景山区 京 0107 110107 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Haidian District of Haidian District People’s 北京市海淀区人 京 0108 110108 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Mentougou Mentougou District People’s 北京市门头沟区 京 0109 110109 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Changping Changping District People’s 北京市昌平区人 京 0114 110114 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Yanqing County People’s 延庆县人民法院 京 0229 110229 Yanqing County 1 Court No. 2 Intermediate People's 北京市第二中级 京 02 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Dongcheng Dongcheng District People’s 北京市东城区人 京 0101 110101 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Xicheng District Xicheng District People’s 北京市西城区人 京 0102 110102 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Fengtai District of Fengtai District People’s 北京市丰台区人 京 0106 110106 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality 1 Fangshan District Fangshan District People’s 北京市房山区人 京 0111 110111 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Daxing District of Daxing District People’s 北京市大兴区人 京 0115 -

Addition of Clopidogrel to Aspirin in 45 852 Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction: Randomised Placebo-Controlled Trial

Articles Addition of clopidogrel to aspirin in 45 852 patients with acute myocardial infarction: randomised placebo-controlled trial COMMIT (ClOpidogrel and Metoprolol in Myocardial Infarction Trial) collaborative group* Summary Background Despite improvements in the emergency treatment of myocardial infarction (MI), early mortality and Lancet 2005; 366: 1607–21 morbidity remain high. The antiplatelet agent clopidogrel adds to the benefit of aspirin in acute coronary See Comment page 1587 syndromes without ST-segment elevation, but its effects in patients with ST-elevation MI were unclear. *Collaborators and participating hospitals listed at end of paper Methods 45 852 patients admitted to 1250 hospitals within 24 h of suspected acute MI onset were randomly Correspondence to: allocated clopidogrel 75 mg daily (n=22 961) or matching placebo (n=22 891) in addition to aspirin 162 mg daily. Dr Zhengming Chen, Clinical Trial 93% had ST-segment elevation or bundle branch block, and 7% had ST-segment depression. Treatment was to Service Unit and Epidemiological Studies Unit (CTSU), Richard Doll continue until discharge or up to 4 weeks in hospital (mean 15 days in survivors) and 93% of patients completed Building, Old Road Campus, it. The two prespecified co-primary outcomes were: (1) the composite of death, reinfarction, or stroke; and Oxford OX3 7LF, UK (2) death from any cause during the scheduled treatment period. Comparisons were by intention to treat, and [email protected] used the log-rank method. This trial is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT00222573. or Dr Lixin Jiang, Fuwai Hospital, Findings Allocation to clopidogrel produced a highly significant 9% (95% CI 3–14) proportional reduction in death, Beijing 100037, P R China [email protected] reinfarction, or stroke (2121 [9·2%] clopidogrel vs 2310 [10·1%] placebo; p=0·002), corresponding to nine (SE 3) fewer events per 1000 patients treated for about 2 weeks. -

December 1998

JANUARY - DECEMBER 1998 SOURCE OF REPORT DATE PLACE NAME ALLEGED DS EX 2y OTHER INFORMATION CRIME Hubei Daily (?) 16/02/98 04/01/98 Xiangfan C Si Liyong (34 yrs) E 1 Sentenced to death by the Xiangfan City Hubei P Intermediate People’s Court for the embezzlement of 1,700,00 Yuan (US$20,481,9). Yunnan Police news 06/01/98 Chongqing M Zhang Weijin M 1 1 Sentenced by Chongqing No. 1 Intermediate 31/03/98 People’s Court. It was reported that Zhang Sichuan Legal News Weijin murdered his wife’s lover and one of 08/05/98 the lover’s relatives. Shenzhen Legal Daily 07/01/98 Taizhou C Zhang Yu (25 yrs, teacher) M 1 Zhang Yu was convicted of the murder of his 01/01/99 Zhejiang P girlfriend by the Taizhou City Intermediate People’s Court. It was reported that he had planned to kill both himself and his girlfriend but that the police had intervened before he could kill himself. Law Periodical 19/03/98 07/01/98 Harbin C Jing Anyi (52 yrs, retired F 1 He was reported to have defrauded some 2600 Liaoshen Evening News or 08/01/98 Heilongjiang P teacher) people out of 39 million Yuan 16/03/98 (US$4,698,795), in that he loaned money at Police Weekend News high rates of interest (20%-60% per annum). 09/07/98 Southern Daily 09/01/98 08/01/98 Puning C Shen Guangyu D, G 1 1 Convicted of the murder of three children - Guangdong P Lin Leshan (f) M 1 1 reported to have put rat poison in sugar and 8 unnamed Us 8 8 oatmeal and fed it to the three children of a man with whom she had a property dispute. -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 12/Friday, January 17, 2020/Notices

3014 Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 12 / Friday, January 17, 2020 / Notices public record and subject to public submissions are subject to verification, respondent selection purposes. disclosure. in accordance with section 782(i) of the Otherwise, Commerce will not collapse Tariff Act of 1930, as amended (the Act). companies for purposes of respondent Michael Fuchs, Further, in accordance with 19 CFR selection. Parties are requested to (a) Acting Director, Office of Finance and 351.303(f)(1)(i), a copy must be served identify which companies subject to Insurance Industries, Industry & Analysis, on every party on Commerce’s service review previously were collapsed, and International Trade Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce. list. (b) provide a citation to the proceeding in which they were collapsed. Further, [FR Doc. 2020–00747 Filed 1–16–20; 8:45 am] Respondent Selection if companies are requested to complete BILLING CODE 3510–DR–P In the event Commerce limits the the Quantity and Value (Q&V) number of respondents for individual Questionnaire for purposes of examination for administrative reviews DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE respondent selection, in general, each initiated pursuant to requests made for company must report volume and value International Trade Administration the orders identified below, Commerce data separately for itself. Parties should intends to select respondents based on not include data for any other party, Initiation of Antidumping and U.S. Customs and Border Protection even if they believe they should be Countervailing Duty Administrative (CBP) data for U.S. imports during the treated as a single entity with that other Reviews POR. -

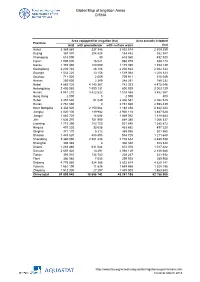

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CHINA

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CHINA Area equipped for irrigation (ha) Area actually irrigated Province total with groundwater with surface water (ha) Anhui 3 369 860 337 346 3 032 514 2 309 259 Beijing 367 870 204 428 163 442 352 387 Chongqing 618 090 30 618 060 432 520 Fujian 1 005 000 16 021 988 979 938 174 Gansu 1 355 480 180 090 1 175 390 1 153 139 Guangdong 2 230 740 28 106 2 202 634 2 042 344 Guangxi 1 532 220 13 156 1 519 064 1 208 323 Guizhou 711 920 2 009 709 911 515 049 Hainan 250 600 2 349 248 251 189 232 Hebei 4 885 720 4 143 367 742 353 4 475 046 Heilongjiang 2 400 060 1 599 131 800 929 2 003 129 Henan 4 941 210 3 422 622 1 518 588 3 862 567 Hong Kong 2 000 0 2 000 800 Hubei 2 457 630 51 049 2 406 581 2 082 525 Hunan 2 761 660 0 2 761 660 2 598 439 Inner Mongolia 3 332 520 2 150 064 1 182 456 2 842 223 Jiangsu 4 020 100 119 982 3 900 118 3 487 628 Jiangxi 1 883 720 14 688 1 869 032 1 818 684 Jilin 1 636 370 751 990 884 380 1 066 337 Liaoning 1 715 390 783 750 931 640 1 385 872 Ningxia 497 220 33 538 463 682 497 220 Qinghai 371 170 5 212 365 958 301 560 Shaanxi 1 443 620 488 895 954 725 1 211 648 Shandong 5 360 090 2 581 448 2 778 642 4 485 538 Shanghai 308 340 0 308 340 308 340 Shanxi 1 283 460 611 084 672 376 1 017 422 Sichuan 2 607 420 13 291 2 594 129 2 140 680 Tianjin 393 010 134 743 258 267 321 932 Tibet 306 980 7 055 299 925 289 908 Xinjiang 4 776 980 924 366 3 852 614 4 629 141 Yunnan 1 561 190 11 635 1 549 555 1 328 186 Zhejiang 1 512 300 27 297 1 485 003 1 463 653 China total 61 899 940 18 658 742 43 241 198 52 -

2017 36Th Chinese Control Conference (CCC 2017)

2017 36th Chinese Control Conference (CCC 2017) Dalian, China 26-28 July 2017 Pages 1-776 IEEE Catalog Number: CFP1740A-POD ISBN: 978-1-5386-2918-5 1/15 Copyright © 2017, Technical Committee on Control Theory, Chinese Association of Automation All Rights Reserved *** This is a print representation of what appears in the IEEE Digital Library. Some format issues inherent in the e-media version may also appear in this print version. IEEE Catalog Number: CFP1740A-POD ISBN (Print-On-Demand): 978-1-5386-2918-5 ISBN (Online): 978-9-8815-6393-4 ISSN: 1934-1768 Additional Copies of This Publication Are Available From: Curran Associates, Inc 57 Morehouse Lane Red Hook, NY 12571 USA Phone: (845) 758-0400 Fax: (845) 758-2633 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.proceedings.com Proceedings of the 36th Chinese Control Conference, July 26-28, 2017, Dalian, China Contents Systems Theory and Control Theory Robust H∞filter design for continuous-time nonhomogeneous markov jump systems . BIAN Cunkang, HUA Mingang, ZHENG Dandan 28 Continuity of the Polytope Generated by a Set of Matrices . MENG Lingxin, LIN Cong, CAI Xiushan 34 The Unmanned Surface Vehicle Course Tracking Control with Input Saturation . BAI Yiming, ZHAO Yongsheng, FAN Yunsheng 40 Necessary and Sufficient D-stability Condition of Fractional-order Linear Systems . SHAO Ke-yong, ZHOU Lipeng, QIAN Kun, YU Yeqiang, CHEN Feng, ZHENG Shuang 44 A NNDP-TBD Algorithm for Passive Coherent Location . ZHANG Peinan, ZHENG Jian, PAN Jinxing, FENG Songtao, GUO Yunfei 49 A Superimposed Intensity Multi-sensor GM-PHD Filter for Passive Multi-target Tracking . -

Names of Chinese People in Singapore

101 Lodz Papers in Pragmatics 7.1 (2011): 101-133 DOI: 10.2478/v10016-011-0005-6 Lee Cher Leng Department of Chinese Studies, National University of Singapore ETHNOGRAPHY OF SINGAPORE CHINESE NAMES: RACE, RELIGION, AND REPRESENTATION Abstract Singapore Chinese is part of the Chinese Diaspora.This research shows how Singapore Chinese names reflect the Chinese naming tradition of surnames and generation names, as well as Straits Chinese influence. The names also reflect the beliefs and religion of Singapore Chinese. More significantly, a change of identity and representation is reflected in the names of earlier settlers and Singapore Chinese today. This paper aims to show the general naming traditions of Chinese in Singapore as well as a change in ideology and trends due to globalization. Keywords Singapore, Chinese, names, identity, beliefs, globalization. 1. Introduction When parents choose a name for a child, the name necessarily reflects their thoughts and aspirations with regards to the child. These thoughts and aspirations are shaped by the historical, social, cultural or spiritual setting of the time and place they are living in whether or not they are aware of them. Thus, the study of names is an important window through which one could view how these parents prefer their children to be perceived by society at large, according to the identities, roles, values, hierarchies or expectations constructed within a social space. Goodenough explains this culturally driven context of names and naming practices: Department of Chinese Studies, National University of Singapore The Shaw Foundation Building, Block AS7, Level 5 5 Arts Link, Singapore 117570 e-mail: [email protected] 102 Lee Cher Leng Ethnography of Singapore Chinese Names: Race, Religion, and Representation Different naming and address customs necessarily select different things about the self for communication and consequent emphasis.